< Previous | Contents | Next >

Beauvale Priory

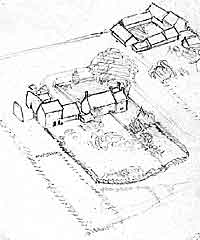

Beauvale Priory in 2002. The Priory was founded in 1343 and is now mostly incorporated in farm buildings. The building in the middle at the top of the photograph is a three-storey tower house, probably the Prior's lodging; the surviving church walls are on the right.

Leaving Kimberley and Greasley, with their rapidly growing populations, and passing along a country lane a distance of a mile or more, we enter the rural spot to which the pleasing term Beauvale would, we presume, be first applied. It is a pretty stretch of pastoral landscape, with verdant fields and hedgerows, and nestling at the side of the hill, within the shadow of the trees, and almost at the head of the vale, is an ancient farmhouse known as the Abbey Farm. Here, in a secluded locality, amid forest scenery, stood for two centuries or more a house of the Carthusian Order, and at the back of the farmer’s residence considerable portions of the monastic buildings still remain.

At the dissolution of the monasteries there were only nine of the Carthusian Order in England, and Beauvale is entered on the list given in Dugdale as one of them. It will be interesting, therefore, to inquire what manner of men they were who occupied this ancient abbey, and gave to it the distinction of being one of the nine English houses which owed allegiance to the Grand Prior of Chartreuse. According to reliable authorities, the rule they followed was similar to that of the Benedictines, but with the addition of a great many austerities. They were the strictest of any of ‘the religious orders, and the use of flesh meat was absolutely forbidden at all times, even to the sick. Each monk lived in his own separate dwelling, and none of them were allowed to go out of the bounds of the monastery except the priors and proctors, and they only to attend to the necessary affairs of the house. An old writer thus summarizes their chief restrictions: ‘They are not to go out of their cells, except to church, without leave of their superior, nor speak to any person without leave. They must not keep any portion of their meat and drink until the next day; their beds are of straw, covered with felt; their clothing two hair-cloths, two cowls, two pairs of hose, and a cloak, all coarse. In the refectory they are to keep their eyes on the dish, their hands on the table, their attention on the reader, and their hearts fixed on God.’ They were enjoined to study, and to work with their hands, their labour consisting in cultivating the fields and gardens, and in transcribing books. Mrs. Jamieson, in her ‘Legends of the Monastic Orders,’ says ‘they were the first and greatest horticulturists in Europe, and of them it may emphatically be said, that wherever they settled they made the desert to blossom as the rose.’ Their habit was all white, except their outward plaited cloak, which was black.

The site sketched from an aerial photograph taken in the 1950s, looking north.

Such was the order of men who, immured in the Abbey of Beauvale, spent their days in labour, prayer, and meditation, and in rigorous observances. If the ruined walls could speak, they could tell us some interesting stories of those who voluntarily gave themselves up to hard work and partial starvation. It was a life of almost entire seclusion from the world, and carried with it the pains and pangs of solitary confinement. It must have required no ordinary fortitude to live without flesh meat, and to fast frequently on bread and water in a locality where the fresh, pure air is a great incentive to the appetite. And what of the restrictions on speech? Were they a sad and silent body, or were the rigid rules ‘more honoured in the breach than the observance’? It is difficult to say, but most writers aver that throughout the period of their existence in this country they adhered more closely to their rules than the vast majority of their brethren, and stood less in need of reform.