< Previous | Contents | Next >

Nottingham

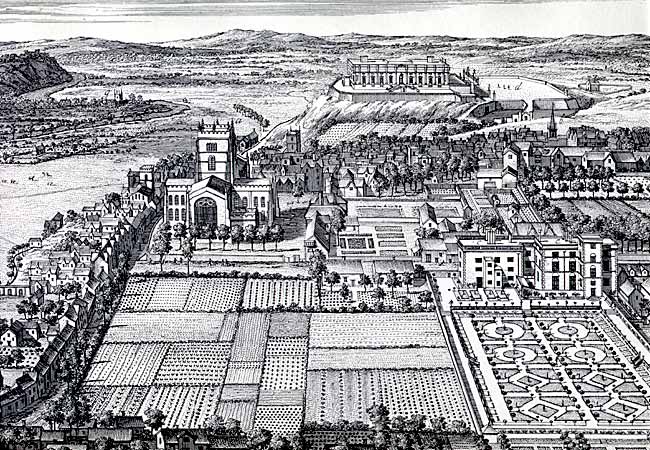

View of Nottingham from the east, c.1709.

ALMOST in the heart of the Midlands, on a commanding site, ‘a city set on a hill, which cannot be hid,’ stands the great town of Nottingham, one of the most important of those busy centres of industry which give to England her commercial pre-eminence, and distribute their famous products over all quarters of the globe. As we stand on the castle rock in front of Nottingham Art Museum, which is so great an ornament to the borough, there lies before us a broad and fertile vale through which the silvery Trent winds his sinuous course, now murmuring beneath the wooded hills of Clifton, or gliding quietly through the green meadows of Wilford, or rushing with swifter force under the wide arches of the Trent Bridge until it is lost to view in Colwick fields. As the eye wanders over this fine stretch of landscape, and then turns suddenly in the direction of the town, it witnesses in its progress a transformation scene as comprehensive and complete as any which the ingenuity of the scenic artist has ever put upon the stage. Instead of the calm repose of country life, we have before us the busy streets of a thickly-populated borough, with its masses of red-brick houses, tall chimneys, great factories and warehouses of many windows, and rising above all, with the fingers of its pinnacles pointing heavenward, the square tower of the old parish church, with all its hallowed memories and its gray, weatherbeaten walls linking irrevocably the present with the past. Very busy and earnest does Nottingham always look in its weekday attire, and, in truth, it is an enterprising and a spirited town, which has pushed its way rapidly to the forefront, won a great name for its staple products of hosiery and lace, and shown all the evidences of healthy and vigorous life. Its modern history is a record of commercial achievement very creditable to itself, and stimulating to its less fortunate neighbours. Let us see what there is to say of its chequered and historic past.

As the name of Nottingham is a puzzle to the etymologist, so its earliest history is enveloped in the mists of antiquity. Mr. W. H. Stevenson has presented all the facts that research can bring to light in a scholarly article on ‘The Early History of Nottingham,’ republished as a pamphlet a few years ago. No satisfactory evidence exists to indicate that the town had a British origin, or to show that it was ever a Roman station. But the site was far too attractive to be long ignored in the gradual formation of settled communities. Taylor, the water-poet, writing in 1639, speaks of the people of Nottingham ‘playing the coney,’ a quaint phrase describing in old-time language how they dug out of the soft Bunter sandstone vaults, holes, and caves as primitive dwellings and habitations, and there can be no doubt that at a comparatively early period it was selected as a suitable place for habitation.

So far as reliable history goes, we have our first glimpse of Nottingham in the time of the Danish invasion. In 869, as the Winchester Chronicle testifies, these hardy warriors occupied the town, and were besieged by Alfred and Aethelred. A treaty of peace was temporarily concluded, but in the spring of 874 they returned in ever-increasing numbers, conquered Mercia, and occupied the five boroughs of Nottingham, Lincoln, Stamford, Derby, and Leicester. Here they remained until Edward the Elder, assisted. by his sister, Aethelflaed, drove them away, Edward’s capture of Nottingham in 919 being, in the words of Mr. Freeman, ‘the crown of his conquests in Central England.’ Edward built a fortress on the southern bank of the Trent in 921, and connected it with the town by a bridge, where his successor, Aethelstan, established a mint, and coins of his, bearing the Nottingham mark, have been found.

Nottingham Castle gatehouse in the mid 19th century.

Then came the struggle at Hastings. Nottingham men were not prominent on that eventful day; the Earl of Mercia was absent, and it was probably because of these abstentions that the Norman Conqueror confirmed so many Thanes in the possession of their lands in this county.

William in due time reached Nottingham, and, as was his custom, immediately began to consolidate his power by the erection of a castle, which William of Newburgh described as being so strong by nature and art as to be able to defy any force but that of hunger. The control of this stronghold was entrusted to William Peverel, a military follower, who built himself a castle of his own on the craggy heights of Castleton, which caused his descendants to be known as ‘Peverels of the Peak.’

After the anarchy of Stephen’s reign, Henry II. insisted upon all the great castles being surrendered into his hands, and the Peverel of the time declining to yield, the King set out to enforce his commands. Peverel secretly retreated in the garb of a monk, and the King took possession in 1155. Under his auspicious rule the town made rapid strides. A royal charter was granted to the burgesses, the Palmers of Nottingham established a hospital for poor men, which Pope Lucius III. protected and assisted by a Bull, and the commercial bodies began to form themselves into guilds, which gradually drew into their own hands the government of the town.

The castle, round which the interest of the warriors of successive ages naturally centred, from its commanding position and unusual strength, remained in the hands of the reigning monarch during the vigorous career of Henry II., and was also controlled by Richard I. until the absence of that King on the Crusades, when it was seized by Earl John, who also possessed himself of the Castle of Tickhill. When Richard returned in 1193, amid the rejoicings of his people, most of the strongholds that had yielded to the solicitations of the King’s unscrupulous and ambitious brother returned to their alliances but Nottingham, always partial to John, held out with unexpected vigour. When an army, led by Lord David, brother of the King of Scotland, approached in the royal interest, it refused to submit, and it was not until the King led the siege in person, in March, 1194, that it yielded to superior force. After the victory, the King, taking advantage of his proximity to the ‘merrie’ forest, of Sherwood, indulged himself in the royal pursuit of hunting, which no doubt formed a pleasant contrast to the stern work of reducing his unruly subjects.

But the enjoyments of the forest had to give place to matters of State. On Wednesday, March 30, his Majesty held a council, which sat for three days, and summoned John to surrender. The Prince boldly defied his royal brother, and after forty days, sentence was pronounced against him, declaring his lands confiscate and himself a traitor. These were strong measures, but, like most great-hearted men, King Richard was not callous to all appeals for mercy. John sought forgiveness, obtained it, had Nottingham Castle restored to him, and resided there in a state of comfort and splendour he hardly deserved.

Upon John’s accession to the throne he visited Nottingham in 1199 and again in 1202. Henry III. held his Court at Nottingham, and granted a short charter in 1229, supplementing it with another in 1255, and a third in 1272, which showed the abiding interest his Majesty took in the affairs of the thriving Midland town.

It was at this eventful period that the movement in the direction of establishing religious houses became most active and fruitfull. In 1250 Henry III. had founded a house in Broadmarsh for the Gray Friars, and in 1276 Reginald, Lord Grey, of Wilton, and Sir John Shirley, Knight, are said to have been instrumental in the introduction of the Carmelite or White Friars, who were located between Moothall Gate and St. James’s Lane, in the parish of St. Nicholas. A reminiscence of the friars still exists in the thoroughfare now known as Friary Lane, where tradition asserts the church connected with the order stood between the Swan Inn and St. James’s Street. The Hospital of St. John was another mediaeval institution where the poor might find shelter and relief. The Borough Records contain references to several grants made to the Hospitallers, and Pope Honorius III. allowed them a chaplain of their own in the chapel, and a cemetery as their exclusive burial-place. Other ancient foundations of this character were the hospitals of St. Michael and of St. Leonard, as well as a free chapel within the walls of the castle itself. Tanner also mentions a cell of two monks at St. Mary’s Chapel in Castle Rock.