< Watnall | Contents | Welbeck (continued) >

Welbeck

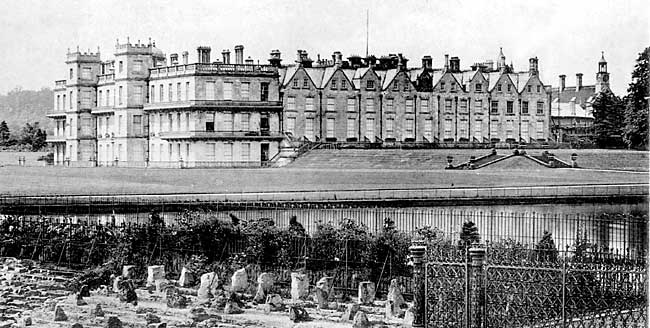

The east front of Welbeck Abbey in 1900.

IN November, 1878, by favour of the late Duke of Portland, I was permitted to visit Welbeck Abbey, and the stupendous works connected with it, for there is no exaggeration in what has been written and rumoured concerning their magnitude. I reached the abbey at eleven o’clock one morning, after a drive of nine miles through a racy air, with just a touch of "winter’s sting." The long grass on either side of the undulating park-drive had a thin, crisp covering of hoar frost, which sparkled in the rich November sunlight, that gave a more golden hue to the dying foliage of oak and elm. I was somewhat disturbed at the outset by the intelligence that one could not see Welbeck thoroughly in less than three of these short days, knowing full well that my stay could not extend over more than one. A brief November day would scarcely afford time to see the works at Welbeck, if you wished to inspect the extensive outbuildings which are, as it were, the outcome of those works. Then there is the house itself, with its grand suites of rooms, rare pictures, and treasures of art from the master brushes of Snyders, Vandyck, Rembrandt, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and a host of other great painters. Welbeck is at once extraordinary and magnificent. A quarter of a mile away from the house there is the perpetual buzz of machinery, and a vast space of ground covered with sheds, in which the newest mechanical inventions are in constant use. The vastness of the work-yards astonishes one ; they might be the premises of some great contractor who had an order for the building of a big village. Very soon after his succession to these immense estates and the titles that go with them, the fifth Duke of Portland commenced a series of improvements on a scale of unprecedented extent, and for upwards of eighteen years Welbeck was in the hands of the builders. During this time his grace devoted something like £100,000 per year of his princely income to the improvement of the Welbeck estate, and some 1,500 workpeople of all classes were constantly employed in carrying out his instructions. The numerous great and expensive works, which are to be seen at Welbeck, were under the immediate supervision of the noble duke himself, who really ought to be described as their architect. When a new building was to be erected he caused a model of it to be constructed, and a flaw or an aspect of inelegance, was detected by him at once. That he was a man of exalted taste in matters of architecture is abundantly manifest everywhere on his estate. The very lodges which dot the park, and which are occupied by keepers and others in his grace’s employ, are models of architectural beauty, and everywhere there are evidences of superb taste, and considerable engineering skill. In the late duke’s time, people applying for employment at Welbeck were able to obtain it—no matter what they were—and the full market value has been paid for their labour.

Late 12th century doorway at Welbeck Abbey.

Welbeck Abbey has a history. It is one of the oldest mansions in the country, though few of its original features are left certainly it has no monastic appearance now. Much of it is new, and the new seems to assimilate with the old so exactly that it is difficult to say what part of the building is ancient and what modern. It is a vast pile, white and castellated, with innumerable windows, overlooking Sherwood Forest, where the immemorial oaks grow, and the deer have a peaceful existence. Before the Norman invasion Welbeck was held by a Saxon, named Sweyn. After the conquest it became part of the Manor of Cuckney, and was held by a family of that name, who founded the abbey, and dedicated it to St. James, in the reign of the Second Henry. After an existence of 398 years, the abbey was destroyed by Henry the Eighth, along with other similar institutions up and down the country. After being occupied by a family named Whalley, and by a London clothworker, the abbey came into the hands of the Cavendishes, who converted it into a noble mansion. In 1619, King James visited Sir William Cavendish at the abbey, and, in 1663, Charles the First was entertained there, with " such excess in feasting, as had scarcely ever been known in England," the abbey at that time being in the possession of the Earl of Newcastle. It passed from the Cavendishes to the Bentincks by marriage. The only remains of the old monastic building, now to be seen, are some arched rooms in the lower part of the house, which are used by certain of the servants. In 1604 the present building was commenced, and being held by a succession of noblemen, each of whom seems to have added some improvements, though on a scale which is utterly insignificant, when compared with what has been done by the late owner, it has developed by easy gradations, until now it is unquestionably one of the most commodious houses in the country. On the occasion of my visit to Welbeck, I had spent the morning out of doors about the " works," in the stables and outhouses, which are on a gigantic scale, and in other of the outworks, and there was only time for a very hasty inspection of the house. The Gothic hall of Welbeck is a gem of architecture, the existence of which is pretty well known. This is part of the old building, which was altered and restored by the Countess of Oxford,—another "Bess of Hardwick," in 1751. The ceiling is a marvel of beauty. It is of pendant fan tracery, delicately and elaborately designed, and the room is splendidly decorated in pure Gothic style in keeping with the ceiling, which I have but imperfectly described. The room contains at least half a dozen rare antique cabinets of ebony and bronze, and of inlaid marble. The large drawing room at Welbeck is a treasure-house. On its walls are hung large and valuable pictures in plenty. The Duke of Portland has one of the best private collections of pictures in England. The walls of the drawing room and of the dining room, which is the largest room in the house, were, and I dare say are now, literally covered with splendid paintings, some of them of great size, and all the works of the best known artists. In the last-named room there are Rembrandt’s famous portrait of himself, a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, of one of the first Earls of Portland, who, when plain William Bentinck, came over on his first visit to England as page-of-honour to William, Prince of Orange, afterwards William the Third. On the accession of this King, William Bentinck was created Baron of Cirencester, Viscount Woodstock, and Earl of Portland, all of which titles are held by the present Duke. This splendid suite of rooms, which forms part of the old house, has recently been extended, and several, what may be, perhaps, not improperly described as ante-rooms, have been added. The new fireplaces are of nickel silver, beautifully white, and highly polished, the mantelpieces being of white marble. Here there are more pictures. There is one of the second Duke of Portland, of that distinguished patriot and statesman, Lord George Bentinck, painted when a boy, and that bright pretty girl, in the pale blue dress, with silver embroidery, is Lady Margaret Cavendish Harley, who, in 1734, married the second Duke of Portland. There is here a portrait of that very plucky woman, Jane Cavendish, who kept garrison for her father at Welbeck against the Parliament army. There are also in these rooms portraits of the two Charleses, that of Charles the First, showing what the monarch was like in his boyhood. At the north entrance to the house there stretches for some distance a lovely little conservatory, which, on this chill November day, is bright with flowers—chrysanthemums and primulas. In what is known as Lady Oxford’s wing at the south front, another story, with a magnificent suite of rooms, has been added to the house by the late Duke. The rooms are very expensively fitted. Most of the walls are of salmon colour, with chastely gilded mouldings, or panels, each panel large enough to contain a life-size portrait, and much of the furniture is in the Louis XVI. style. A finer suite of rooms than this could not be seen anywhere, with their tall mahogany doors, oak floors, elegantly guilded cornices, and mantel-pieces of pure white marble. If I remember rightly, the late Duke added fourteen new rooms to the Oxford wing, and all these are decorated and finished with the utmost purity of taste. Occasionally in this wing one comes upon some choice imitations of Gibbon’s carving, the work of an Edwinstowe artist. The carving of the marble mantelpieces, it should be stated, has been executed by workmen employed at Welbeck. In the sitting room of the late Duchess, which is in the old part of this wing, there is a fine chimneypiece of marble, inlaid with Wedgewood’s sage green plaques, In order that furniture and other heavy things may be conveniently moved, the mansion is supplied with hydraulic lifts, which are constructed to work from top to bottom of the house, and in this way furniture is removed from one story to another. There was an hydraulic shaft connected with the kitchens, and the dining room can be supplied by means of a small waggon, which, lowered by the shaft ran upon rails along one of the underground passages. These rails—which are something like the rails of a tramway, terminate at a kind of iron cupboard, which is heated by steam, and in this the viands can be placed, and kept hot until they are required for consumption in the adjoining room. An underground passage is connected with the old riding school, which is entered by a trap door, opened by means of a crank. Only the few who have seen this great room can form any conception of its proportions, or of its magnificence. In the Duke of Newcastle’s time it was used as a riding school—now it is put to a nobler use. It is used as a museum of art, containing long rows of choice paintings. There must have been several hundred pictures in this room—portraits and landscapes by famous artists long since passed away. You walked between avenues of pictures and of books, for there are several thousand volumes there, piled up in stacks upon the floor. The floor of this magnificent art gallery is of polished oak, and the inner portion of the roof, which is in the style of Westminster Hall, is painted to represent a glorious sky. The tall doors are wholly, and the walls partly, covered with looking-glass, which gives effect to what would make one of the finest banqueting halls in the kingdom. The glass alone in this room must have cost an almost fabulous sum. Four cut-glass chandeliers, each weighing nearly a ton, are suspended in a line from the roof ; from the hammer beams are twenty-eight smaller cut-glass chandeliers, and on the walls are fastened sixty-four cut-glass brackets or side lights. There are in all 2,000 gas lights in this grand apartment. What must be the effect when all these are lighted? The roof outside is covered with copper, and two turrets have been erected. In them are placed a set of clocks, which have been very fittingly described as marvels of constructive skill. Mr. Benson, of London, speaks of them thus "In a set of clock calendars which I some time since provided for his Grace the Duke of Portland, the clock showed the time on four dials, five feet nine inches in diameter, quarters, hours, &c. (the well-known Cambridge chimes), on bells of 12 cwt., repeating the hour after the first, second, and third quarters. The two sides of an adjoining tower show a calendar, which indicates on special circles of a large dial, by means of separate hands, the month of the year, the day of the month, and the day of the week." This building, like the others, which have been erected by the Duke of Portland, is connected with the house by underground passages. There are some miles of these passages at Welbeck. They lead in all directions, and are very pleasant to walk in. One of them, which leads from the house to the works, diverging to the riding school, was used only by the late Duke. There is a passage leading from the house half way to Worksop, and you can walk underground in that direction for fully twenty minutes ; there is another which takes one some distance into the park, and others leading to the library and cellars. These passages are constructed on a uniform principle, and they are wide enough to allow three people to walk abreast. They are lighted both by natural light and by gas. The light is admitted from above through circles of plate glass, which are placed in round frames. Appearing at intervals of about every ten yards amongst the grass of the park, these circular arrangements would puzzle any person who was not in the secret. In the passages gas is always burning. The tunnels are built of brick with a covering of hard plaster, and are perfectly free from damp. The floor is composed of some kind of pulverised stone, very pleasant to wall upon. Where the tunnel crosses a road, light is most ingeniously admitted from the side. The library at Welbeck, to which the finishing touches are now being given, is underground. It is a magnificent building, the work of long years. It is parallel with the picture gallery, and is divided into five large rooms, the ceilings of which are level with the surface of the park. The doors open one into another, so that the rooms can be made to form one great whole. The mahogany windows open into a long corridor covered with glass, and the whole building is effectively heated by steam pipes. Down below the earth’s surface there is not a sound to be heard in any one of the rooms, and a soft and subdued light is admitted through the large octagonal plate-glass arrangements in the ceiling. The library comprises reading rooms, and a room for periodicals. The cornices and ceilings are very handsome. The total length of the library is 236 feet, and there are ample facilities for lighting the rooms with gas, there being in all about 1,100 burners here. Closely adjoining the library is a subterranean apartment of magnificent proportions, into which the light of heaven is admitted by about forty large octagonal sunlights placed in rows in the vast ceiling. It was suggested that the Duke meant this for a church, but there is nothing ecclesiastical in its appearance. No, it is not a church. It looks more like the very antithesis of a church—a ball room, and what a ball room it would make! Its floor is of oak, and it massive roof supported by iron girders. At one end it is entered from above by means of a spiral staircase; at the other it is approached by subterranean passages. Its flat ceiling is beautifully ornamented, and the eight iron girders which support it are of massive proportions. The room has been, as it were, dug out of the solid clay; it was commenced five years ago, and to-day workmen are very busy within its spacious walls. This underground building, of which there is such a quantity at Welbeck, strange though it may seem to those who read about it, has certain special advantages. There is not the slightest suspicion of draught in these rooms, they are thoroughly heated by steam pipes, are perfectly free from damp, and the means of lighting employed is most successful.

< Watnall | Contents | Welbeck (continued) >