< Previous | Contents | Next >

Linby

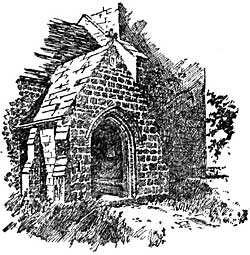

The north porch, Linby.

WILLIAM Peverell, the younger, granted to God and the Church of Holy Trinity at Lenton and his brethren serving God, the town of Lindby and whatsoever he held in it, viz., lands tilled and unfilled, in wood and plain, in meadows of pastures, with the church of the same town and the mill of Blaccliff, for the treasures which his mother bestowed on that church, and he compelled by very great necessity took; and for all other excesses in which he, by the instinct of the enemy against that church imprudently had exceeded, contrary to the command of his father, and the bargain which he made with him and witn his mother.

William Abbat, of Leycester, and Robert, of Kenelingwrd, by the authority of Pope Alexander 3, made an agreement that Robert, priest of Edingla, who gave the monks of Lenton, five marks, should hold the church of Lyndeby while he lived secular, paying that Priory half a mark of silver yearly at Martinmas in the name of a pension which one Henry Clarke was to have also, if over-lived Robert, paying the like pension William Curfun, dark, obliged himself to make it a whole pension to the Convent of Lenton, when there should be a solid establishment made of the parsonage and vicarage which, Adam, the chaplain, was to acquit him of, so long as the said Adam continued in secular habit.

Without tracing fully the history of the ancient village of Lindby we might mention several interesting facts in connection therewith. In the fifth year of the reign of Edward II. the jury found that John Metham held by reason of Sibyll, his wife, . . the moyety of the Town of Lindeby by the rent of a skin of gray furr, and one mess and two cars of land in Willey by the services of 10s. to the exchequer.

The Domesday reference to Linby is as follows:— In Lindebi three brothers had one carucate of land and a half to be taxed land to two ploughs and 12 villanes and two bordars, having five ploughs. There is a priest and one mill of 10s. Wood pasture one mile long and one mile broad. Value in King Edward's time 26s. 8d., now 40s. This entry is under lands of Wm. Peverel, who in 1105 gave amongst other churches and lands the church of Linby to Lenton. Linby was partly in the forest, for in the Perambulations of 1232 we read: "From that castelry (i.e. Annesley) by the great way and the town of Lindeby and thence by the middle of the town of Lindeby to the mill of the same town which is on the water of the Lena." There were four places where the Attachment Courts of Sherwood Forest were held, and Lindby was one. In the 14th century the ferme of this place is frequently mentioned as belonging to the Manor of Mansfield. The Patent Rolls of Richard II. have an entry as follows:—1378, May 3. Westminster: Presentation of John de Sileby, chaplain of the chantry at the altar of St. Mary's, Newark, to the church of Lindeby in the diocese of York in the King's gift by reason of the alien Priory of Lenton being in his hands on account of the war with France, on an exchange of benefices with Richard de Tuttebury. Long before this, to be precise, in 1314 a grant was made during pleasure of farm and soke of Lyndeby to Margaret, late the wife of John Comyn, who was killed whilst on the King's service in Scotland, for her sustenance, and that of her son Aymer. A grant for life (Patent Rolls) was made to John de Burlegh, Kt., of 100 marks yearly from the King's manor of Mammesfeld and Lyndeby upon his surrendering the following grants, viz.: that of 15 March, 30 Ed. III. being a grant of £40 yearly at the exchequer: that of 1 April, 47 Ed. III. being a part or 40 marks yearly in addition, and that of 27th January last being a confirmation of the foregoing in consideration of his being retained to stay with the King. This was vacated by surrender and cancelled because at his application the King granted the said sum of 100 marks yearly to his son John de Burlegh, Kt., Oct. 25th. This was in 1378.

Also dated from Westminster four years later were—Letters patent to Walter Archbishop of York, dated Scroby 5 noe Jul in 16 year of his pontificate confirming them in possession of pensions of one mark from Linby Church.

Queen Isabella was granted for life in furtherance of a resolution of Parliament that for her services in the matter of the treaty with France, and in suppressing the rebellion of the Despensers and others, the lands, etc., assigned to her by way of dower should be increased in value to 20,000 a year, castles, honours, manors, towns, lands, tenements, hundreds, farms, and rents to the value of £8,722 4s. 4d. Among the list contained in the calendar of Patent Rolls, Ed. III. is the soke and farm of Lindeby. Subsequently the Queen assigned Lindeby, with other lands to the King, and was compensated by Parliament for the same.

Sir John Byron, Knt., had a grant, 28th May, 1540, of the Priory of Newstead with the manor of Papplewick and Rectory of the same with all the closes about the Priory, etc. Four years later the advowson of the church of Linby was given to Robert Strelley and Frideswide, his wife.The church is small, consisting of nave, chancel, south aisle with chapel, tower, north porch, and vestry. The original foundation is Norman, and was perhaps begun by Wm. Peverel for, as already mentioned, he, according to Domesday Book displaced the three Saxon possessors, thereby becoming tenant in chief. All that remains of the Norman period are the plain inner door of the porch with tympanum, devoid of ornament, and a good deal of the walling, the latter being easily detected by its characteristic masonry. In all probability this church was aisleless, and the addition of the south aisle was made in the reign of King John or early in that of Henry III. The nave arcade belonging to this alteration now remains, and consists of three bays with pointed arches, supported on octagonal columns. The caps are decorated with nail head ornament, and the west respond has a cable mold carved in it, and above on the abacus, small patera. The bases have good moldings, but they are much chipped. Perhaps about this time, also, a tower was first erected as the tower arch is plain and supported on corbels of an Early English character, and judging by the length of the nave and chancel, it is quite possible that until this time Linby possessed no tower. In the south aisle is a piscina with a trefoil head and small shelf above the basin. This latter is the credence or table on which the chalice, paten, and other things necessary for the celebration of mass were, before consecration, placed in a state of readiness on clean linen cloth. The alterations did not end here, for the chancel was renovated, and two windows remain at this period in its south wall, the first with two pointed archea under the hood mold, and the second a smaller one-light, with a trefoiled head. On the north side of the chancel is a small aumbrey also with a trefoiled head. In the reign of Edward III. the only alteration would be the insertion of windows, notably that at the east end of the south aisle with its reticulated tracery. Richard II. took into his own gift the church of Linby in 1378 because of the French wars on account of its belonging to the " alien" priory of Lenton. After this time the next building was in the 15th century, in the Perpendicular style, the most important alteration being the rebuilding of the tower, and the least noticeable the insertion of the east window, now modern, and perhaps one in the north aisle. The tower has no buttresses and is surmounted by four pinnacles. In the belfry the windows are two-light, and the west window a three-light, the tracery in the head of which is now blocked up. In regard to the Strelley connection with this place we might here add that at an Inquisition taken at Nottingham, the Thursday after Palm Sunday, 23 Henry VII., before Sir William Perpoint, Knight, Edward Stanhope, Knight, and Ralph Agard, John Strelley died seized of the moyety of Lindeby, Mar. 4, 2. H. VII. leaving his son and heir Nicolas Strelley above twelve years old.

Elizabeth, mother of the said John, the year following was married to James Savage, Esquire. From Strelley it went to Staveley by the marriage of a daughter. In Elizabeth's reign there was a recovery, and it is said to quote Thoroton, that Mr. Savile and Sir John Byron made an exchange between this and Oxton. John, the second son of Sir Nicholas de Strelley, married Joane, the daughter of Wm. Mering, Esq. Their son, Sir Nicholas Strelly, Knight, married Elizabeth, daughter, and one of the heirs of Sir Brian Fitz-Randolph, Knight, who died without issue. But to conclude our description of the church. To the time of the advowson in 1548 Linby was probably indebted for its north porch, which has panelled angle buttresses with shields carved thereon. In the centre of the gable are the Strelley arms and on the buttresses are two shields, the one on the left containing a fleur de lys charged on a saltire, and that on the right three fusils conjoined per pale. The roof is vaulted, and east of the door is a small trefoil-headed squint, the use of which is not clear, for it does not point to the altar, as is usual, but away from it. It may have been used in connection with some outside ceremony or may be merely a freak, built in its present position when the porch was made. In the east window in the south aisle are two bits of old glass apparently 14th century work, one piece being the top of a canopy, and the other a crowned head. In the churchyard, reared up against the east end of the south chapel, is a remnant of an old stone which, from the carving upon it, may have been used to mark the resting place of an abbot, seeing there is a pastoral staff cut upon it.

In the 18th century Linby Church presented a bare appearance. On the north aide the only features to break the bareness of the plain walls were the porch and a square-headed debased window of four lights, placed near the east end of the nave wall.

In the south chapel on the east wall is a stone bearing the following inscription:—

In this little chappelle under the tow gravestones with crosses, lyethe George Chaworth, Esquire, and Marye, his wiffe, the daughter of Sir Henry Sacheverelle, Knight, late farmers of this mannor place and demesnes of Lynbye betwine whom was issue three sons and three daughters; which Geo. dyed the two and twentieth of August Anno dm 1557, and Mary, his said wife, died XV. of June Anno dm 1562, on whos sowells God hath mercie.

On the south wall of the church is a stone fixed in loving memory of Louisa Mary Weddall, wife of the late William Langstaff Weddall, M.A., vicar of Darsham, Suffolk, who died April 14th 1891, in the 81st year of her age. The tablet was erected by her affectionate and only son, the rector of this parish. On the opposite wall of the chanoel is a stone to the " much lamented memory of Henrietta, wife of the Rev. Thos. Hurt, junr., Rector of this parish, and daughter of Wm. Unwin, Esq., of Sutton, in this county, who died February 28th, 1806, leaving issue one child.

There is a stone let into the north side of the chancel, inside the altar rail, with a Latin inscription, a free translation of which is as follows:—

"Hard by this wall lies the body of Wm. Seddon, for many years minister of this church, who at the sight of the Anglican Church gasping for life, himself became breathless, and rendered up his life to God, through Christ on the 28th day of February, 1684, aged 50.

His mortal life, death came and took away,

The pattern such lives leave, no death can slay."

This was at the time, it will be observed, when James II. was trying to re-Romanise the Church. The stone lettering is in places obliterated, and two Bishops failed to decypher it, we understand. By the side of this is another stone, the lettering upon which runs as follows:—

Underneath by this wall lyeth the bodie of Dorothy wife of Will Seddon, rector of Linby and daughter of Will Burnell, of Winkeburne, Esq., who lived piouslye, and died November 17, 1679, aged 73.

An inscription beneath the handsome east window states that the stained glass window was fixed to the memory of Andrew Redmond Prior, Catherine, his wife, and Sophia Louisa Hearle Stephens, their daughter. It was erected by the Rev. I. L. Prior, M.A., rector, and his three surviving sisters.

The Linby burials date back from 1692. There is a memorandum in 1695: Lord Byron died November 13th, about halfe an hour after nine of ye clock at night, and was laid in ye vault at Hucknall Torkard ye 16th day about 8 of ye clocke at night.

Other entries somewhat out of the usual order are extracted:—

1698. Letitia Townd row, widdow, Poor.

1699. Benjamin Jackson, a poor blind man.

1699. Sept. 10th, Thos. Rogers, a Batchelour.

1701. July 9th, Catherine, wife of Sir Wm. Stanhope.

1714. Dec. 2nd, Henry Davenport, a Batchelour.

1730. June 6th, Richd. Page, aged about 100.

1739. Jan. 17th, Robt. Cottingham, aged 103.

1750. Wm. Cloud, a traveller.

In the year 1801, London boys were buried on Jan. 5, Feb. 25, Mar. 11

(two), May 5, 12 and 13, June 16, July 16, 2, 4, 27.

1760. Diana, daughter of the 5th Lord Byron.

1801. Thos. Pilborough, a London boy at Mr. Robinson's cotton works.

1701. Nov. 12th, Catherine, wife of Sir Wm. Stanhope buried.

The marriages and baptisms date from 1692. In looking through the registers we frequently came across entries under the heading of deaths: "A London boy." As no name accompanied the entry we were curious as to the omission, and also to the frequency with which the deaths of London boys were recorded. The Rector enlightened us on the subject, and we confess to having found nothing so pathetic in the registers of the Deanery. Towards the close of the 18th century, and the beginning of the next many boys from London workhouses were drafted down to Papplewick to work in the large flax mills, and the entries we have referred to are records of their deaths. No fewer than 14 of 19 burials which took place at Linby in the year 1801 were those of poor little London boys. Close to the north-east boundary wall of the churchyard lie the bones of scores of these little paupers, who were brought from the great city workhouses to end their days in the flax mills. There is no doubt these youngsters would be compelled to work long hours which, of course, was not unusual in those days, and the story told to-day is that they were very ill-fed, and consequently the weaker ones soon found a resting place in God's acre. Did the Workhouse authorities enquire into the manner in which the children, of whom they had assumed parental control, were treated?It is not very likely! If the little fellows were unable to stand the physical strain imposed by long hours of toil in heated room and poor nourishment, there were plenty more in London workhouses to take their places. "One hundred and sixty boys," said the Rector, "were starved and murdered in this way—three and four a week sometimes being placed beneath the grass in the churchyard."

The machinery at the mill at which these paupers worked was driven by water power, and it is stated, with what amount of truth we cannot say, that it was owing to the cruelty these children were subjected to, that Lord Byron dammed up the stream which worked the mill wheel, and suddenly letting the water free swept away the machinery and half the mill. A costly and lengthly law suit followed, and Mr. Weddall assures us that the handsome marble chimney-piece, still to be seen in the drawing-room at Papplewick Grange, is part of the compensation his lordship paid for the damage he occasioned. He brought it from Greece. There is no doubt that Lord Byron defended an action at law causing damage to the machinery, but whether designedly, to wreak vengeance upon the wealthy mill owner for nis inhuman treatment of the juveniles from the city, we know not. No stone marks the resting place of these unknown children who lie in one long line close to the churchyard wall, which skirts the road to the colliery.

Standing at the entrance gate to the churchyard and looking towards the village maypole, a house, which rises above the other buildings will be noticed. This for many years was the residence of the Stanhope family. Sir Wm. Stanhope married Catherine, daughter of Richard, second Lord Byron, the register informs us. Beneath a sycamore tree, close to the farm house, the infant son of a Stanhope was one day placed by his nurse, and in her temporary absence, was killed by a wolf. To the memory of his child the father had a large and handsome marble monument erected in the church, and it remained there for many years. But as it occupied so much of the limited space of the interior the Rector had it removed and buried in the churchyard near to the tower. The present Rector has been unable to trace its whereabouts, but he has the assurance of an old resident, who saw it removed, that it was "interred" in God's acres near to the tower. In the south chapel, some little time ago, when the walls were stripped of their colour wash, two large frescoes were discovered. They were paintings of negroes heads one being a very large one. No reason can be assigned for such peculiar mural decoration, and they were again washed over with colour.

The following is the Torre list of Rectors:— John, chaplain of the King.

1267. Will Wythan.

1268. St. Bartholomew's Day, Ric de London.

1286. Aug., Mic the Norman.

1336. Will Veysair, of Ledes (pauper clericus.)

1341. Ric de Grymeston. (Resigned for the Mediety of the Church of Tyreswall.)

1353. Feb. 16. John de Hemyrgburgh.

1376. Rad de Tutbury. (Resigned for the deanery of Leicester).

— Will Vale. (Resigned for the church of Belshesford, Lincolnshire).

— Thos. Ingham. (Resigned for church of Saxby, Lincolnshire).

1418. June 19, Will Parrington.

1424. Tho Blythe.

1443. Mar. 9, Robert Smyth.

1447. April 18, Joh Stubber.

1460. Aug. 2, Will Temple.

1462. July 4, Robt. Breeban.

1466. Jan. 9, Ric. Bonay.

1467. Dec. 23, Joh Verdon.

1477. May 27, Gilbert Cowper.

1481. Dec. 22, Joh Tildesley.

1505. April 17, Tho Morland.

1533. May 13, Tho Dunwell.

1569. May 23, Joh Chambers.

1575. Sept. 6, Edw. Holte.

Edw. Helton.

1604. Aug. 1, Lach Sanders.

1632. Nov. 8, Ric Meires.

We are unable to trace, even with the assistance of the names from the Torre manuscript a complete list of the rectors of Linby. Torre does not mention the name of John de Sileby, who, according to the Patent Roll, was rector in 1378, nor that of Johannis Werdun, who according to the learned vicar of Blidworth, was rector in 1518. This information Mr. Whitworth obtained from a Derbyshire register, from which he read that in 1529 Robert Pym, of Linby, killed John Karbock of Paplewyk, for which he got a pardon on condition he would serve King Edward over sea for a year at the King's wages.

Thomas Martyn was rector of Linby, and he died in 1723. An. Mathews was another rector, and he died in 1729. John Abson followed him, and for many years the Rev. Robt. Stanley held the living. The registers show that his wife died in 1776, but we find the rev. gentleman signing the registers up to 1792. The Rev. Thos. Hurt, from a stone in the churchyard, we notice was born in 1773, and died 1853. Edward Ridmond Prior, followed, and then in 1876 the present rector, the Rev. Charles W. Weddall was inducted to the living.

In the days of the Commonwealth, too, we know from the Parliamentary Inquiry of 1650, that Richard Walker, was the rector. He appears to have been a strange kind of man if the finding of the Commission, as to the rev. gentleman's character, is at all reliable. We must not forget, however, that the men who sat as commissioners were not favourably disposed towards the church, and we might therefore accept their reference to the minister cum grano salis. Here is the entry taken from the original MSS. in Lambeth Palace library:—

Linby—worth £40 per ann . . . Richard Walker, clerke, present incumbent, receives proffits to his own use being preachinge minister, but is a Drunkard and a common swearer. There are four bells, and they contain the following inscriptions:—

- T. Mears, London, fecit, 1826. G. Swinton, churchwarden.

- T. Mears, London, fecit, 1826. Rev. Thomas Hurt, Rector.

- T. Mears, London, fecit, 1826. Andrew Montague, aged 11 years, 1826.

- T. Mears, London, fecit, 1826.

There are no other marks on the bells, and the lettering is Roman in character.