III.

We next turn to a matter of a totally different kind. Though Dame Nature denied the possibility of a coalpit to the old borough of Nottingham, our forefathers lacked not enterprise to put the matter to the test. The following interesting item was entered on the minutes of the town council for the 5th of March, 1594-5:—"Agreyd with Robert Hancock for 10d. a daye, and hys too workemen 10d. a peoe, to dygge in the Copyez for serche of coles, and to be provided of yron wurke, to wit, 2 mattocks and a shovelle, a herryng barrel; and to begynne at the furtherest at Our Ladye Daye." Commenting on this entry, our county analyst, Bailey, says:—"The spirit of speculation and enterprise at this time prevalent amongst Englishmen, in refer ence to foreign discoveries appears likewise to "have begun to manifest itself in stimulating projects at home of a character scarcely less romantic than those which were being undertaken abroad. Amongst these manifestations may certainly be classed that of the corporation of Nottingham undertaking to dig for coal in that part of their estates known to the townspeople as the Coppice. What geological indications had revealed themselves, at that time, to the eyes of learned members of the corporation, or their surveyor, to induce them to enter the bowels of the earth in search of coal on their estate, we know not."

Bailey further remarks that the enterprise does not appear to have been prosecuted with much vigour, and as a matter of fact we hear nothing further about the labours of Robert Hancock and his two men. Nevertheless, although temporarily abandoned, the project of a municipal coal mine must have continued to simmer in the minds of the governing body, for it was revived some five-and-thirty years later. On the council minutes for the 13th of September, 1630, we find it recorded that the Mayor, Mr. James, Mr. Nix, and Mr. Greaves had "undertaken to sincke a pitt or pitts in the towne's woods and waste, in hope (by the favours of God) to fynde ooales there, and all others thatt shall nowe, before the worke begynne, adventure a partt or proportion of monie, shall have oute of the workes and coales, for everie 20s. laied out £5, and soe after thatt rate." Thus the enterprise took the form of a company that intended to pay 500 per cent, on borrowed money. It was further agreed that, after work had been actually started, "none shall be admitted to adventure in anie wise." The promoters of the scheme were to be allowed all timber necessary for their operations out of the town Coppice and wastes. Besides money being advanced at will by members of the corporation, it was arranged for certain persons to go through the several wards, soliciting monetary support, on similar conditions, from the burgesses at large, &c. However, the ill-fated scheme aigain collapsed, for we learn nothing further of it until nearly twenty years later.

THE LAST OF THE COPPICE PITS.

Eventually the matter came to the surface for the third and last time. On the council minutes for the 14th of February, 1648-9, occurs this brief item: "Coppice. Master Cooper to tamper and deal with Master Jackson privately, and not as from the house, how hee wold deale about it to suffer the Towne to gett coale." Nearly a year Later, on the 10th, of January, 1649-50, occurs the following entry: "Coales. Agreed that Master Chamberlins, with ye assistance of Master Fillingham and Master Hawkings, shall conferr with men of Judgment, and such as they like of, and use indevors and meanes to discover whether or noe there bee Coles in the Copies, and to bee allowed for thr paines and charges therein."

In the burial register of St. Mary's, Nottingham, under date 12th April, 1650, this significant entry appears: "[Blank] of Sturley drowned in a Cole pit." On the council minutes for 7th May, 1650, we read: "Coales. It is agreed that ye parties imploied by ye Towne proceed, further to try for coales by sincking a new pitt, and otherwaies as shalbee fitt." On the 6th of September following this entry was made: "Coales. Resolved by this company, in respect of the force of ye water, and the greatnes of the charge in sinckinge, that the pitts bee sunck noe deeper; and that soe soon as may bee, they make triall by boareinge, whether coales or noe coales in ye Coppice." Here, then, we have the necessary key to the otherwise inexplicable entry in St. Mary's register. Practical colliers had evidently been engaged at Strelly (otherwise Sturley) in connection with the Corporation undertaking. We have evidence of the workings becoming flooded, and one of the colliers was drowned. Nobody knew the poor fellow's name, and they probably cared as little. There can be no moral doubt that such is the explanation, although Mr. Godfrey, in annotating St. Mary's registers, failed to elucidate the record. The last scene in the history of this burlesque of a coal mine is thus entered on the Council minutes for 7th November, 1650:—"Pitts. Agreed, ye pitts to bee covered; or else some one to take ye wood for ther labor to fill them upp; and Master Jackson and Master Hewood first to have notice hereof." Bailey, writing half a century ago, says, "The site of these pits is still easily discernible," but fails to indicate their locality.

FUEL OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.

We may now resume our notes on the local coal industry within the past three centuries, when we begin to get the jottings and notices of travellers and topographers. First we have the famous William Camden, who visited Nottingham about the year 1600, and in his description of the town, published 1610, says: "On the one side Shirwood yeeldeth store of wood to maintaine fire, although many use for that purpose stinking pit cole, digged forth of the ground." Speede, 1610, dealing with the county, describes it as "for waiter, woods, and Canell Coles abundantly stored." (The word "canell" is believed to be a corruption of "candle," being applied to coal burning with a bright, clear flame, and said to have been used for candles.)

A quatrain of (unknown authorship was current in the early part of the 17th century as follows: —

I cannot without lye and shame,

Commend the Town of Nottingham;

The people and the fewel stinke,

The place is sordid as a sinke.

These lines, together with Camden's allusion to "stinking pit coal," aroused the ire of the anonymous author who wrote an interesting account of Nottingham in 1641, and who consequently enters into a lengthy disputation over the comparative merits of various kinds of fuel then in use. As some of his remarks contain useful local information, throwing light on our subject, we append some relevent passages: "The first sort of (of fuel) then to ibe examined is Wood in its proper nature, not metamorphosed; the next is the stone Coal got about Nottingham and other Inland neighbouring Countries, which in the getting rises many times as big as the Body of a Man. A third sort there is: the small caking Coal got about Northumberland, used in all the maritime Countries in the East and South Parts of the Kingdom, and in London itself, which bv some is called Seacoale, because it comes by Sea, though I ha.ve heard some Cockney of Opinion it was got in the Sea, by reason of that Appellation. It is called by some Newcastle Coal, because it comes in Ships from Newcastle. But in Property of Speech they are truly neither Newcastle nor Sea Coale, no more than the Stone Coal got at Wollaton, Strelly, and Bramcoat may be called Nottingham Coal or Trent Goal, because they are conveighed from Nottingham by the River Trent to Newark, Gainsborough, and other Places . . . .

A PREFERENCE FOR COAL.

"If we look into the Practice of those Countries where wood and Coales are, whether we respect the Houses of Noblemen and Gentlemen, or Corporations and Market Towns, we shall find even where there is equal Store of both Sorts that the Coals are chosen for the Chimney before Wood. As in all other places, so in Nottingham, where they have Store of both kinds, they make Choice of Coal rather than Wood, which they have in such Plenty as he who at Night when he goes to Bed has not an handful of fuel, may the next Morning in the shortest Day in Winter have Coales brought to his Door to dress his Dinner with a blessing that few Towns of the Kingdom can boast of. I could name some Towns myself of no mean note, who remote from ye Coale Mines, and trusting to be served with Fewel by Water, when some frosty Winters have shut up those Passages, the People have been constrained to burn Stools, Chairs, Formes, and Bed stockes for want of Fewel. What Reason then can this Detractor have to upbraid this Town with the Baseness of their Fuel, who use none but of the best kinds, I leave to the Censure of the judicious and impartial Reader."

Here, then, we have conclusive evidence as to the universal consumption ot coal in the county town bv the first half of the 17th century, apparently by rich and poor alike, with notice of a daily house-to- house supply. The distribution by water as far as Newark and Gainsborough is likewise instructive. The referenoe to the situation of the pits, viz., at Wollaton. Strelley, and Bramcote, introduces the two latter places for the first time, although it is quite possible the works had been in operation there for centuries before. We have already mentioned the tragic death of a Strelley collier in the trial works at Nottingham Coppice.

Childrey's "Britannica Baconica," 1661, remarks that: "In this shire are abundance of pit coals."

Passing on to Thoroton's "Antiquities of Nottinghamshire," 1677, it is disappointing to find our great county history almost a blank so far as this ancient local industry is concerned, although, in his introductory remarks (p. 1), acknowledging that a part of the shire bordering on Derbyshire "affords most excellent coals." Village after village in the coal-producing district the historian passes over without so much at a hint or clue to the mining operations we know were being contemporaneously carried on. In fact, so far as we can find, except for an incidental allusion to Wollaton coals, in connection with the tradition concerning the building of Wollaton Hall, there appears to be only a single brief reference, which relates to the ancient mine or mines of Strelley, viz., "The Coals, the chief profits of Strelley. are not so plentiful now as formerly." The fact that the revenue from this industry was the main source of income is sufficient evidence of its importance, although the field was then apparently showing signs of exhaustion.

THE NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COALFIELD.

The chapter on coal is very interesting. "Coal" is the old name of charcoal, and "collier" was a charcoal-burner, or possibly it may have extended to a dealer. I do not think charcoal was ever burnt in or near Nottingham. The cost and difficulty of carriage of the unburnt wood was enormous, compared with the finished article. It was burnt, and is so now, In the woods, where the raw material and the fuel were naturally found. Charcoal-burners' huts are often alluded to as pictures in the woods. I do not think manor woods, like that of Nottingham, would be drawn upon for this trade. They were too limited and too, valuable, and bound up with too many interests to admit of it. It was a trade pursued in woodland districts or forest land, largely in Kent and Sussex, where the iron trade was formerly located, and where the forests were destroyed for this purpose when the old smelting with charcoal came to an end, and the iron trade moved to the northern coalfields, and an inferior iron to the "charcoal blooms" was and is produced. Coal, as a domestic fuel, would be early used in East Derbyshire, where the beds come to the surface, and carts can be backed into the face of them. The next stage would be sinking pits, say 20ft. deep, and mining the coal—men at the top with a windless winding it out in baskets, the same as the working of wells. I have seen these details still existing in Derbyshire.

Coal is deeper in Notts, and mining must have been well advanced before the business was introduced. The coal was conveyed about in baskets or panniers, on the backs of horses and asses, down to the time of the introduction of canals, and the first canal in Nottingham came down from the Erewash Valley, and terminated at the town, on purpose to supply it with coal. This accounts for it being brought through Wollaton. At a later date the branch from Lenton to Beeston was made, and at a later date still the branch from the present Great Northern Railway Station, on London-road, to the Trent, below the Trent Bridge.

The Nottingham people expected getting their coals much cheaper when the canal opened, but they did not. As a boy I have spoken with old men who were living then.

The old fuel of Nottingham was wood, tanners' knobs, and coal. Bakers heated their ovens with dry gorse, and it was stored on the north side of Derby-road, opposite the Roman Catholic Church. There was a great fire there. Someone put a light to it. Tanners' knobs were still burnt in my time. They are alluded to by Deering in the rock-houses in Hollow-stone. When a boy, our next neighbour was a lover of John Barleycorn. His wife, deserving of a better husband, kept the house by doing lace-work and letting her father a one-room floor, where he had a stocking-frame, a bed, and some odds of furniture. He burnt tanners' knobs in his room, and I well remember the stink in the neighbourhood. I never had the curiosity to see what they were like, but I have an impression they consisted of the spent bark from the tanpits. There was, or still is, a Knob- alley, or yard, in Narrow-marsh.

I remember the old coal carts about the town, and the "Coal Ho!" men weighing it on beam scales fixed on the sides of their carts. One of these merohants was a woman, Mrs. Cope, a widow, with an upgrown son, a soldier. She lived in Sawyers' Arms-yard, Greyfriar-gate, and went with her horse and cart to Radford Pits, vended the coal about the streets, wore a smock-frock and men's heavy boots, and so got a living sixty years ago. The father of a present-day Nottingham timber merchant kept a canal coalyard, and retailed coal. He had a number of wheelbarrows to lend customers who wanted half- hundredweights, &c., at their houses. It was common to see women wheeling these barrow loads of coal to their own houses, and taking the empty barrows back. I take it that women are still to be seen getting in loads of coal, and that loads of coal are allowed to be shot up in the streets—a strange custom not seen here, where it is all weighed and carried in bags.

We burn Yorkshire coal. It differs from yours, leaves very little ash, and that brown, and it cakes or runs together when burning, and it is all soft coal. I have never seen any hard coal here.—W. Stevenson, Hull.

IV.

It is a matter of regret that so little material is accessible respecting the local history of our present subject. No doubt, however, there are sources of information as yet untouched. The court-rolls and private archives of certain districts are bound to contain instructive matter if they could be overhauled. Again, even Church documents, such as churchwardens' accounts and parish registers, in appropriate localities, would almost certainly afford helpful notes and hints. Yet again, a little local investigation would infallibly reveal certain ineffaced evidences of the coal mining industry in places where it has been discontinued, in the form of refuse heaps and abandoned workings. Futhermore, the traditions and recollections of old inhabitants are by no means to be despised by the would-be historian. By the way, if one or more of the long-disused pits could be safely explored, instructive evidence of obsolete systems, as well as, perhaps, ancient tools and other relics, might be found.

A moment's reflection will show that volumes of history lie sealed up for ever in the abandoned coal-workings of this neighbourhood, integral parts of the life of the village communities for centuries, although their records are singularly sparse. The perils of flood, gas, collapsing roofs, descending and ascending the shafts, &c., were certainly present, formerly, as now, and in ruder times must have been proportionately more fatal. Numberless un-chronicled tragedies must have transpired, and many a mouldering skeleton yet lies unsuspected deep down beneath the feet of modern villagers.

The following entry on the minutes, of Nottingham Town Council for 16th June, 1699, reflects attempts at monopoly, then somewhat widespread—"Whereas complaint hath beene made unto this hall by severall of the inhabitants of the said towne, that diverse persons within the said towne, who have and keepe places and yards for laying of coales, in order to sell the same againe, have bought such excessive quantityes of coales, and doe forestall and hinder the bringinge of coales to the towne, whereby coales are become verry scarce and deare: Itt is therefore ordered that the persons who are guilty of the said offence shall be discharged (i.e., forbidden) for so doeing. And in case they shall persist and continue to buy and forestall coales, until the inhabitants of the said towne sihalbe furnished with coales, that they shalbe prosecuted for the same, according to lawe."

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY REFERENCES.

We now pass on to a comparatively modern authority, viz., Deering's "History of Nottingham," written about 1745. Like the writer of 1641, Deering, in his list of the number of tradespeople, does not include any coal dealers, through some oversight or other. He refers, however, as his predecessor did, to the coal traffic by water, from Nottingham, down the river Trent. Furthermore, in dealing with the products of the country immediately around Nottingham, Deering supplies the following interesting paragraphs:—"And first Pit-Coals, since the almost universal destruction of wood in the Forest, is become the only Fewel used here, for which end there are Coal-Mines within 3, 4, 6, and 7 miles, north-west and west of this town, which, being worked, furnish to it plenty of Coal, at a reasonable rate, for they are never above 4d. to 6d. per Hundred, unless when a wet winter season has made the roads very bad, for which great advantage Nottingham owes an everlasting gratitude to the memory of the late, and the person and family of the present Lord Middleton.

"The Coals of this country, though they do give way to those which come from Newcastle to London in durablenese, and consequently are not altogether equal to those for culinary uses, yet for chambers and other uses they exceed them, making both a sweeter and a brisker fire, and considering the difference in price these are divers ways preferable:— A Chaldron of Coals, which should weigh full a Tun Weight, is at the cheapest at London, in the Pool, £1 3s., besides carriage, whereas the dearest, i.e., at sixpence per Hundred, we have a Tun of our Coals brought to the door for 10 shillings. The Coak or Cynder, which is used for the drying of Malt, and which is sold at 1s. and 4d. per horse-load, is much sweeter than that made of the Yorkshire Coal, which appears in that the Nottingham Malt has hardly any of that particular taste which the Yorkshire Malt communicates to the best of their Ale."

Emmanuel Bowen, on his map of the county, about the year 1750, says: "On the western side, bordering on Darby-shire, there is found in several places a most excellent sort of Coal, of the same Nature with ye Pit coal of Lancashire and Yorkshire, but more unctious and sulphurous."

G. M. Woodward, a visitor to Nottingham, 1796, in the course of a diatribe against the town, says, "The streets are, in general, covered with sludge of the blackest kind, which sable hue is principally contracted from the dust of coal carts." Further on Woodward says: "Leaving Nottingham at Chapel Bar, a dirty coal-road presents itself, and a laborious ascent brings the traveller to the windmills before noticed, which are left on the right. During this short passage it is pleasing to observe that every little hut, whether cut in the rock or slightly bound together with bricks and mortar, displays (through his humble casement) the glowing comforts of a cheerful coal fire. How much superior is this appearance to the dreary situation of the poor in Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, and the neighbouring counties, who are frequently pronounced (by their wealthy superiors) as having nothing to wish for." This writer continued on the road by Lenton and Wollaton Park, mentioning that "on the right are several coal-pits, chiefly the property of Lord Middleton."

THE LOCAL HISTORIES.

Next we turn to Throsby, the county historian, whose work on Nottinghamshire was completed in 1797, and contains the following notes:—

Bilborough. "In this lordship, which is open fields, there are considerable coal-works. It is owned by Thomas Webb Edge, Esq. The Collieries are leased to a Mr. Walker and a Mr. Barber; coals are got here a 100 yards deep."

Brinsley. '' On this estate are two collieries."

Eastwood. "In it are extensive coalmines. Coals are found here a the depth of five yards, and at fifty . . . . . . The coal-mines here afford great pleasure to the naturalist. Mr. Gervas Bourne, who resides in this place, has a most valuable collection of fossils, partly from the bowels of the earth here," &c (Throsby gives a plate of sketches of fossil leaves.)

Teversall. "A coal-pit near Teversall," &c.

Wollaton. "This lordship, which is small, abounds in pit-coal."

So much for Throsby, who omits much information that he might easily have included. The development of the canal system about this time no doubt exercised a proportionate influence on the coal-trade. Laird, 1813 (who makes passing allusion to the difficulties of keeping the roads in repair in the coal districts) states that the principal object of the promoters of the Nottingham Canal was the export of agricultural produce, coal, &c. Elsewhere he says that coals "are becoming very valuable to their proprietors from the increased sale arising from the facilities of water carriage, and as they are now both cheap and plentiful the encouragement to lime-burning will naturally increase, to the manifest improvement of agriculture." Dealing with the parish of Radford, Laird says:—''In this neighbourhood are many coal-pits, in which the coals are dug out in large masses; and it is said that they possess the inflammable principle or gas in a greater proportion than any other species of the fossil in the kingdom." Yet again Laird remarks:—"The supply of coal, an article of such importance, may be supposed to be on a cheap and convenient scale, as Nottingham is in the immediate vicinity of very extensive coal-pits. Yet it has been a matter of complaint that the increased facilities of water carriage. have actually raised the price upwards of 50 per cent. This has been attributed to a 'combination against the poor, but it is more likely to have arisen from the extension of the country to be supplied, in consequence of the new canal cuts, having been greater than the usual supply of the pits was equal to."

NINETEENTH-CENTURY ALLUSIONS.

The Charity Commissioners, in the early part of the 19th century, dealing with the Nottingham charity of Abel Collin, who in 1704 bequeathed funds for the purchase of coals in summer (when at their cheapest) for distribution in winter, report:—"It is stated that in consequence of coals being now brought by the canal to Nottingham, there is little variation in the price of them in the course of the year, and that the application of these sums as directed by Mr. Collin would be of no utility." However, in view of the fact that the seasons affect the price of coal even in the present day, despite the enormously increased facilities for carriage and distribution, it is questionable whether the above statement, by interested parties, was not merely a plausible excuse for the diversion of the charity that had already taken place.

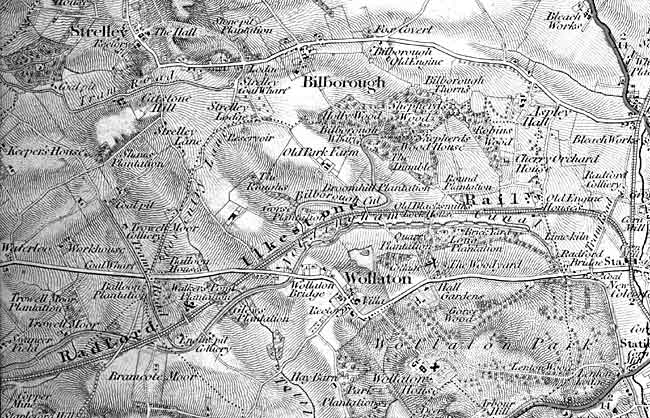

"Coal pits," north of Strelley Park, are the only ones indicated on Greenwood's map of Notts., 1826.

White's first Nottinghamshire Directory, 1832, contains several interesting notes. It refers to Bilborough mines as having "long been exhausted," and mentions "extensive collieries of Barber, Walker, and Company," at Brinsley. Cossal Colliery is described as "exhausted many years ago." (Nevertheless, Curtis, about 1844, says: "Coals are got in this lordship at about 60 yards in depth, and of an average thickness of three feet; the Babbington pits are much deeper.") White states that the coals at Eastwood had "all been got," and adds this curious anecdote:—"A wonderful story is told here of a farmer being swallowed up alive in the parlour of the village alehouse, whilst he was swallowing a cup of ale, to the great surprise of the host, who by this means discovered that his mansion was built on an exhausted coal mine."

THE OLDEST NOTTINGHAMSHIRE RAILWAY.

White further mentions the "Baggalee Colliery, worked by Barber, Walker, and Co.," at Newthorpe, Selston Colliery, Skegby Coal Mine, and ''Strelley Park Colliery, whence coals are conveyed on a railway to the Nottingham Canal." He omits reference to the Wollaton pit, but refers to one "belonging to Barber, Walker, and Co., at Watnall Chaworth." Besides the Strelley Railway, White refers to another one at this early date, as follows: "The Rail-road from Mansfield to Pinxton, in Derbyshire, opens a communication with the Cromford Canal, and the numerous branches of inland navigation to which that canal has access. It is seven miles and three-quarters in length, and was commenced under the powers of an Act of Parliament passed in 1817, but was not completed till 1819. At its western extremity it joins the Pinxton Canal basin, and is terminated at Mansfield by an extensive storeyard and warehouses, which are surrounded by a stone wall, and bear the name of Portland Wharf. It is of great advantage to the inhabitants in the central part of the county, for it affords a cheap and expeditious transit for the coal of Derbyshire, which is brought in large quantities to Mansfield, for supplying both the town and a large district extending many miles to the eastward, where the farmers and other inhabitants have frequently to send their waggons or carts to Mansfield, for coal, stone, and lime. Before the formation of this rail or tram road, the price of coal at Mansfield was generally from 10s. to 13s. per ton, but it is now seldom higher than 8s. or 8s. 6d. per ton.

"About a mile south-west of Mansfield the railway crosses a deep glen, near the King's Mill, by a stupendous bridge of five arches, and though the undertaking cost an immense sum of money, it now pays per cent, to the shareholders. One horse will draw upon it as much as would require five horses upon a common road, so that it is of considerable service to the quarry owners of Mansfield, by opening an easy and cheap communication with the inland navigation, for the immense blocks of stone which are sent hence to the western and southern counties. Steam carriages have not vet been introduced in Nottinghamshire, though they have long been used on some of the colliery railways in the north of England, and may now be seen propelling both heavily-laden waggons and coaches on the Manchester and Liverpool Railway, at the amazing speed of from fifteen to twenty miles per hour."

The old Ordnance Map, 1839, indicates collieries or coalpits at Radford, Strelley, Watnall, and Wollaton, as well as divers tramways and wharves. The immense developments of the Nottinghamshire coalfield during the past sixty years lie outside the scope of the present sketch.