Holme by Newark Church

A MERCHANT PRINCE BUILDS

St Giles' church, Holme.

MASTER JOHN BARTON, Merchant of the Staple of Calais, stepped out of his front door and looked critically at the new home he had recently completed. A long rambling many-gabled stone manor house, with smallish windows, leaded in diamond panes, with here an oriel and there a square bay window, in the manner of Henry VII's reign, then just commencing.

As he stood there in his scarlet coat, furred with martin, his silver girdle and his coral rosary, he was pleased with himself. He had made a pile of money out of the wool trade and he was not at all ashamed of the fact. His sheep were all around him in the broad pasturage which he owned; his great lumbering wagons were in the barns and sheds behind him; he had a solid amount of gold coin of the realm in his strong boxes hidden away within. From small beginnings he had gone steadily on until now he was able to dine off silver plate, and his clothes were as good as anyone's. In the presses lay his best coat of camlet and others of crimson with velvet revers, of violet lined with frieze and with say, and of red furred with mink, besides another handsome silver neck chain. He felt equal to anyone in the land.

He had a largish family—four sons and two daughters—and everything pointed to their settling down in solid comfort as lords of the Manor of Holme by Newark, now he had built the house and enlarged the church.

From where he stood he could see, across two fields, the parish priest, his confessor, Sir Thomas Tylling, entering the church, and he was pleased with its appearance.

Fired by the zeal of his trade rivals, Master John Tame of Fairford and Master Thomas Fortey of Northleach, who had built such splendid churches at their Gloucestershire homes, and tired of the perpetual bragging of their wealth and devotion he had emulated them. He had been determined to show that old John Barton was as good as they were and could afford to spend just as much on his house and church as any of his brother wool merchants.

Certainly the sheep had paid and he was grateful, and rather proud of being a self-made man.

There in the windows of his home he had recorded the fact in the rhyme painted on the glass and carved on the stone, 'I thanke God and ever shall, It is the shepe hath payed for all'.

True he had not a coat of arms, but his wife's, which he had appropriated, did just as well and looked impressive carved over the stone fireplace in the hall.

When he first knew the church it was a dismal, narrow, aisleless building with no windows in its north side, and he had shown his gratitude to God, who had prospered him, by well-nigh pulling it down and doubling its size, with an aisle and a Lady Chapel for the burying of his own kin and the seating of them at service times.

Never mind about the north wall which he had left untouched—he could not see it from his windows, and he had put a couple of good windows in the chancel opposite his own pew.

He had flooded the place with light and the windows blazed with many-hued glass in which saints, prophets and his own family, kneeling in prayer, were pictured.

The pews and stalls were new, carved by the best workmen he could find, their ends showing dogs, lions, chameleons, dragons and other fantastic beasts. The walls glowed with the colours of the heraldry of his family alliances:—and he had not forgotten to include his trade mark and the arms of his trade guild—on stone and glass everywhere. Even his initials were stamped for ever on the work and 'J.B.' with his cunning rebus—a bar across a tun—could be seen about the church in many places. The shields looked gay in their brightly-painted tints, and the newest style had been adopted throughout. True, he preferred the older mode which he had ordered for most of the windows, but those in the chancel were in the latest Tudor fashion, very plain and severe, with simple rounded arches.

He liked, too, the stone tomb with the figures of himself and his wife, Isabella, which he had caused to be erected in his own part of the church, the Lady Chapel, just between the two altars of chancel and chapel. There they were, painted to the life—he with his rebus at his feet, she with her pet dog— but, plague it, the wife had already complained that the dress in which she was taken was old fashioned !

Lest they should grow too proud and heedless he had made the carver put a stone corpse underneath to remind them each day they went to church that, despite his wealth, they, too, must go the way of all flesh.

The family wanted to put a row of coats of arms across the porch, but he didn't know about it. It seemed a little too ostentatious. Better wait till the old man was gone and then they could do as they liked.

But there was the hell ringing for mass, and if he did not stop dreaming he would be late.

CHANGE AND DECAY

The Reformation produced its inevitable result of neglect, indifference and deliberate damage, and with the temporary suppression of Catholicism the Church gradually sank into an appalling state. A slight check was given to Elizabethan irreverence when, under Charles I, Archbishop Laud succeeded in recovering some of the decencies of public worship. But this was eclipsed by the Puritan Commonwealth and only partly revived under the later Stuarts. With the coming of the Hanoverian Georges, Protestantism attained its greatest ascendancy, the evils in the Church immensely increased and remained for nearly a century and a half, until the Oxford Movement, by recalling men to the fact that the Church of England is Catholic, succeeded in awakening the Church and abolishing the disgraceful condition into which it had fallen.

Holme was no exception to the general neglect; as long ago as 1871 Archdeacon Trollope declared it 'had been greatly injured by neglect and ill-treatment'. In 1905 Mr. T. M. Blagg, F.S.A., wrote of its 'three centuries of absolute neglect'.

BEFORE RESTORATION

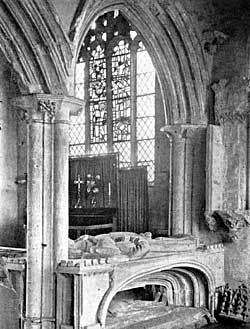

Tomb and east windows before restoration.

It is well to describe its state in 1932 before the author of this book began to restore it.

The altar rails had been painted brown and grained. Every window save one was patched, broken or ill-fitting, letting wind and rain into the church. The mediaeval glass which remained was jumbled together inside-out and upside-down and its leads were so weak that a gale would have blown it out altogether. Large holes had actually been left open in the mediaeval glass so that more fell and was lost. Thick deposits of whitewash and dirt blackened, and in many places completely hid, both its colour and design. The carved canopy of a large niche had fallen to the floor wfiere also lay the statue belonging to it. Some of the upper lights of the east window in the choir were blocked with bricks and cement, while others were filled with hideous plain glass in crude colours. No seats remained in the choir which, however, contained an iron deed box, a bed-room chair, and a coal scuttle, while a common office arm-chair was in the sanctuary. Three coke stoves with pipes reaching to the roof were actually placed in the middle of the chancel and the centre of both aisles and completely ruined whatever artistic appearance still survived. A vast Victorian 'clothes horse' pulpit extended from the south side of the rood screen as far as the door of the Lady Chapel and hid the whole of the bottom half of the screen on that side, being built right into it by hacking away the ancient screen. The font cover was in a dirty state. The porch room was inches thick in bird-droppings and debris with its broken windows boarded up for the last twenty years.

Nearly all the rood screen tracery and the base panels of screens and stalls were missing, and other work had been intruded into the rood screen; the floorboards of pews and stalls had rotted so that one's feet stood on the earth. A tree was growing out of the tower. The sanctuary had been raised wrongly, thus hiding the base of the fine tomb. The altar was covered with an old torn shawl and a red felt frontal. Half of the chapel screen door had gone. The south-east door was plastered up, the north door blocked and the whole church was surrounded with 10ft. high elders which in summer made it impossible to see out of the windows or to get near to the walls, besides continuously damaging the fabric. Decayed stone mullions had been cheaply replaced in wood! In the tower a massive beam was ready to fall on the people below. The return stall on the south side of the chapel had disappeared. The stone altar was invisible—buried in the floor under a wooden platform.

The whole place was in an astonishing state of absolute neglect, dirt and decay, the more conspicuous because it is comparatively rare nowadays; even matters which voluntary workers and a few shillings could have put right were neglected.

What made matters sadder was that when a little money was once spent on the building it was upon entirely wrong treatment. The stone floors were replaced by red and black hall tiles; the walls were stripped of the plaster which they were designed to receive, and pointed in black cement giving a most gloomy effect.

THE RESTORATION

The nave walls, robbed of their preserving plaster and whitewash, had become crumbling and spongy: to correct this they were lime-washed which has brought light and cheerfulness back to the church. Mediaeval churches were almost invariably white-washed.

The ancient stone altar slab was found to bear all its five incised crosses, but owing to its smallness it was probably the side altar and was set up again in the Lady Chapel to serve its original purpose for the Blessed Sacrament.

The intruded sanctuary step was removed, the original level restored, the base of the tomb revealed, and the Victorian tiles replaced by York stone flags. New riddel curtains, a frontal of Portuguese design, a silver Flemish crucifix and six candlesticks were given. The altar rails were cleaned from paint and waxed.

The three stoves and pipes were taken out. The rood screen was repaired and the pitch pine intrusions replaced by oak properly moulded, the rood figures added and the screens coloured and gilded.

Deal boarding which had been nailed on the front of the screen was removed. The tower vestry was stripped, re- plastered and whitened and the unsafe beam replaced. In the Lady Chapel the statue and its canopy were refixed and a spirelet for which no place could be found was inserted in the other niche to give the 'feeling' of the missing statue. The missing panels in the three screens and chapel stalls were supplied and the carvings which had in times past been removed and put in the screen, were restored to the stalls. Simple new return stalls were made for the choir and those in the chapel were repaired.

The modern wooden mullions with which the west aisle- window had been patched were replaced by stone.

The porch room windows were reglazed—a gift from the glass artists, Messrs. King of Norwich. The other windows in the church were reglazed with clear glass in rectangles.

A brick patch in the nave parapet was replaced by stone, and the tiling mended. The belfry tree and all the ciders were cut out.

The Tower Screen.

The mediaeval glass was cleaned, reconstructed and reunited in the east window central lights, quarries from the nave supplied the gaps in the tracery lights, which were opened where bricked up, and fourteenth-century glass was obtained for the outer lights.

Fifteenth-century standard candlesticks, an oak bishop's chair, a pulpit crucifix and several pictures were given. The 'spider' candelabra was repaired, plated, coloured and hung in the nave.

An oak screen for the tower vestry, and a new pulpit and font cover were made, also a priest's door after the original design.

The architect was Mr. K. Harley-Smith, who had as consultants Mr. A. R. Powys, Sec. of S.P.A.B., and Mr. William Weir.