< Previous | Contents | Next >

East Retford church – the chancel.

THE CHANCEL. One step leads from the space under the tower into the chancel, which is 45 feet long and 19½ feet wide. Before 1855 it was only 28 feet long, but it was then re-built on the old foundations, and made the same length as it had been before the tower fell in the 17th century. At the same time a clerestory was added and the roof was raised. The additions can be easily traced by the smooth machine-cut stone, that bane of all modern buildings. To suit the increased height of the chancel, the mullions of the east window were lengthened, but the old tracery was preserved. This is of a decorated character, verging on the Flamboyant, and is a fine example of its style. To appear to advantage, it should be seen from the outside, where the design of the tracery is not blurred by the designs of the stained glass.

The oak choir stalls, made from designs by Mr. C. Hodgson Fowler, were given as a memorial to Mr. T. Wagstaff and Mr. J. H. Robinson, two churchwardens, who both died in 1888, during their term of office. The clergy stalls were also given in memory of the same two men.

The altar is raised on six steps. Behind it is a stone reredos, put up when the chancel was lengthened, and north of it is a carved credence table worthy of the same period. On the outer panels of the reredos are carved and painted the Ten Commandments, the Creed, and the Lord's Prayer. Within the altar rails is a carved oak chair, to be used by the Bishop at Confirmations; this was carved by Mr. Edwin Swannack, Jnr., and was presented by him to the Church in 1894.

On the south side of the chancel is a small room with a chamber above, which served as the vestry before the present chantry was re-built. It is now used as a sacristry.

The Organ. An arch on the south side of the chancel opens into the organ chamber, which was one of the additions made to the Church in 1855. Before this time the organ had been in the gallery at the west end of the Church.

This gallery was built in 1770 at the expense of Robert Sutton, who also bought an organ from the theatre at Newark and presented it to the Church. At a vestry meeting held on January the 25th, 1795, it was resolved that the use of the organ should be discontinued after Easter, and that the organist's salary should in future go towards buying a new instrument, a rather original way of raising money. The new instrument was made by Donaldson in 1795, but it was only small, and in 1841 a larger one was built by Walker, of London. In 1886 this was much enlarged and practically re-built by Brindley & Foster. It is now a large fine instrument with three manuals, forty stops, and about 2,000 pipes. The keys are worked partly by pneumatic, and partly by tracker action, and the swell is controlled by a balance pedal. Unfortunately it is still blown by hand in the old-fashioned way. We must hope that before long electric power will be available.

The Chantry. Till 1873 the north transept was bounded on the east by a brick wall, and it was only on its being taken down to build the present chantry, that it was discovered that this wall concealed two arches and the pillar which supports them. These arches are probably the oldest part of the Church, and were built in the middle of the 14th century when the original chantries were endowed. The pillar is octagonal, and the capital is well carved with vine leaf foliage, as is also the corbel which supports the arch on the north. The corbel which supports the southern arch is modern. When the wall was taken down, three of the original bunches of grapes with which the arch was painted were still visible. These were darkened and the decoration completed with bunches of a similar character.

The present chantry of the Most Holy Trinity and St. Mary forms an eastern aisle to the north transept, and serves both as a morning chapel and a vestry. It was built from designs by Mr. G. F. Bodley in 1873, and was opened on the 6th of October of the same year, by Dr. Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln. It occupies part of the same space as the ancient chantries, but these extended much further eastward, their foundations being discovered when the present building was erected.

An oak screen separates it from the north transept, and in 1898 oak panelling was put round the walls. On the south wall hangs the picture of the Last Supper, painted and given by William Rose in the middle of the 18th century. It has little artistic merit. The other pictures in the chantry are some of the Arundel Society's reproductions of ancient masters.

The chantry is entered from the outside of the Church through a small lobby. This has been re-built and widened during the present year. It now measures 14 feet long by 9 feet wide, and serves as a kind of outer vestry.

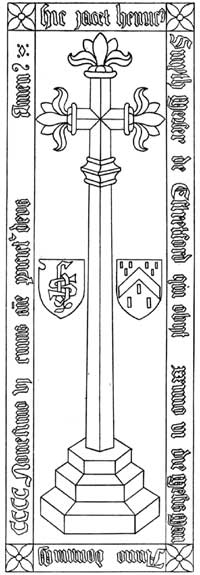

MONUMENTS. Few monuments of any interest remain in the Church, many floor stones having unfortunately been destroyed at the restoration of 1855. When Piercy wrote, there was a handsome raised tomb in the north transept to John Rowley, who died in 1404, but this was wilfully destroyed in 1840 in order to allow more room for the archdeacon's visitations, which were then held in this part of the Church. Close by, on the floor, was a marble stone in memory of Henry Smyth, Mercer, who died in 1496. This is now in the chantry and is the oldest monument in the Church. It is still in good preservation, and the incised cross is almost perfect, though some of the inscription is worn away.

Tombstone of Henry Smyth, died 1496.—In Chantry. From a drawing made by Mr. E. A. E. Lambert.

The accompanying illustration is taken from a drawing made by Mr. E. A. E. Lambert, of the Grammar School. The following is a translation of the inscription:—

"Here lies Henry Smyth, Mercer, of East Retford, who died on the 26th day of the month of May in the year of the Lord 1496, to whose soul may the Lord be merciful."

Near to the north clergy stall, before the tiles were put down in 1905, was a stone with an inscription then hardly decipherable, but it was copied in 1876 by the Rev. E. Collett, and read as follows:—

Richardus Dixon, Chirurg: ob. die Aprilis 27mo Anno Domini MDCCXCVIII Aetat. suae 23tio Tam bene doctus, tam cito abreptus ! Heu flebilis adolescens. Translation:—"Richard Dixon, Surgeon, died 27th April, in the year of the Lord 1798, aged 23." The rest cannot be properly translated, the beautiful word flebilis especially having no English equivalent. It means "much lamented" or "deeply mourned," but has none of the vulgarity attaching to these expressions. The words may be paraphrased:—

Thy wisdom rich, thy life so short, Alas, O youth, we mourn for thee.

Numerous tablets are fixed to the walls of the Church, which commemorate, for the most part, those who died between the middle of the 18th and the middle of the 19th centuries, and which are as tasteless as might be expected from the period at which they were put up. If the inscriptions are to be believed, Retford at that time must have been peculiarly fortunate in the virtues of its inhabitants, among whom the first place must be given to the wife of Josias Cockshutt, Esq., as a tablet on the east wall of the south transept records that, "in her were united every religious, moral and social virtue." This paragon died in 1770, aged only 19 years. Truly, whom the gods love die young!

Near by is a memorial to Robert Sutton, who died in 1776. He was a person of some consequence in his day, and held various public offices, among others that of gentleman usher to Queen Caroline, wife of George II. The inscription is devoid of fulsome flattery, but his numerous generous gifts are recorded. It was he who gave the first organ to the Church, and he also gave much money for the improvement of the town. The bridge on the Carr over the Idle was built by him. The inscription calls it Pelham Bridge, a name now almost forgotten. A strange figure in the streets of Retford must this same Sutton have been, with his scarlet coat with broad ruffs, his waistcoat trimmed with gold lace, and his cocked hat on the top of his fullbottomed wig. He was senior bailiff in 1773, and tried hard to reform the old Corporation. When he failed, he resigned his aldermanship, and to show his contempt for the general corruption, sent round the crier to offer his official robes for sale.

Near the west door is a monument to Sir Wharton Amcotts, who died in 1807, and who was descended on the female side from George Wharton, who, early in the previous century, gave a field in the Dominie Cross to the Head Master of the Grammar School, on condition that he should read the Common Prayer every Sunday afternoon in the Church of East Retford. The monument states that Sir Wharton Amcotts represented this "respectable borough" in parliament during 20 years. As a matter of fact, this same "respectable borough" was one of the most corrupt constituencies which could be found in a corrupt age. Every freeman was accustomed to receive £40,even when the candidates were not opposed. And at the election of 1826, the drink bill alone amounted to £3,811 7s. 0d. Happily, this election finally led to the disfranchisement of this "respectable borough."

On the wall of the baptistry is a heavy Georgian monument to several people of the name of Lane. A Latin inscription of no great interest says they were members of an ancient and noble house. No date is given, but the monument was put up by Stephen Rose, the father of William Rose, to whom there is a memorial on the wall east of the south door, and who died in 1753. It was this William Rose who painted and gave to the Church the picture of the Last Supper, which used to be in the chancel, and which now hangs in the chantry.

Tasteless and heavy as are these records of a past century, the only one that has been put up in modern times is equally unsuited for a Gothic church. It is placed under the south window of the south transept, which window was given in 1903 in memory of those who fell in the South African war. The inscription is as follows:—

To the Glory of God

and

To the Memory of those of the Sherwood Rangers

Imperial Yeomanry

Who died for their

Sovereign and Country in South Africa 1900-1902

| Lieut. A. C. Williams | |

| Sergeant A. F.Tomlinson | Corporal G. Duckmanton |

| Lee. Corpl. G. W. Webb | Trooper F. Kempster |

| Trooper F. Bell | F. Kirk |

| R. W. Bond | ,, F. E. Lowless |

| ,, T H. Bowness | „ E. J. Mackinder |

| „ A. F. Clark | „ H. Oglesby |

| „ J. Hall | „ G. Pepper |

This window was dedicated by their Friends.

"Not once or twice in our fair island-story, The path of duty was the way to glory."

On the wall of this south transept is a memorial to Alderman Beaumont Marshall, who died in 1826. After a record of virtues which one can only envy, a vivid touch is given: "He was enabled by Divine Grace" says the inscription, "to support a tedious illness with comparative patience and resignation." What a world of suggestiveness in that word comparative!

On one or two monuments will be found a pathetic record of the death in infancy of almost a whole family, possibly swept away by some of the virulent epidemics of the pre-drainage days. In the south transept is a tablet to the Rev. Richard Morton, who was vicar of the parish for 49 years, and who died in 1821. Six of his eight children are mentioned as having died before him, four of them in infancy. In the north aisle, attached to one of the tower piers, is a record of five of the children of John Holmes, who died between 1794 and 1813.

After the death of Mr. Morton, the Rev. T. F. Beckwith was appointed to the living, which he held for 32 years. There is a monument in memory of himself, his wife, and three children, on the south side of the west door.

The Windows. Before the Reformation, the Church was probably rich with the beautiful glass with which the medieval artists adorned their buildings, a glass whose colouring has never yet been equalled in modern times. But to the Puritan it was hateful and idolatrous When Archbishop Laud was impeached, one of the charges against him was, that he had set up in his chapel at Lambeth, Popish images in stained glass. Thus by the middle of the 17th century, the only stained glass in East Retford Church was in the great west window. Thoroton, the historian of Notts., writing in 1677, describes the various shields and heraldic devices of which this window was then composed. But these, too, must have been afterwards destroyed, for in 1828 no trace of them remained.

There are now over twenty stained windows in the Church, all of which have been put in since the middle of the 19th century.

On the wall of this south transept is a memorial to Alderman Beaumont Marshall, who died in 1826. After a record of virtues which one can only envy, a vivid touch is given: "He was enabled by Divine Grace" says the inscription, "to support a tedious illness with comparative patience and resignation." What a world of suggestiveness in that word comparative!

On one or two monuments will be found a pathetic record of the death in infancy of almost a whole family, possibly swept away by some of the virulent epidemics of the pre-drainage days. In the south transept is a tablet to the Rev. Richard Morton, who was vicar of the parish for 49 years, and who died in 1821. Six of his eight children are mentioned as having died before him, four of them in infancy. In the north aisle, attached to one of the tower piers, is a record of five of the children of John Holmes, who died between 1794 and 1813.

After the death of Mr. Morton, the Rev. T. F. Beckwith was appointed to the living, which he held for 32 years. There is a monument in memory of himself, his wife, and three children, on the south side of the west door.

THE WINDOWS. Before the Reformation, the Church was probably rich with the beautiful glass with which the medieval artists adorned their buildings, a glass whose colouring has never yet been equalled in modern times. But to the Puritan it was hateful and idolatrous. When Archbishop Laud was impeached, one of the charges against him was, that he had set up in his chapel at Lambeth, Popish images in stained glass. Thus by the middle of the 17th century, the only stained glass in East Retford Church was in the great west window. Thoroton, the historian of Notts., writing in 1677, describes the various shields and heraldic devices of which this window was then composed. But these, too, must have been afterwards destroyed, for in 1828 no trace of them remained.

There are now over twenty stained windows in the Church, all of which have been put in since the middle of the 19th century.

Since that time the manufacture of stained glass has been steadily improving, but many of the windows having been given at the beginning of this period are very crude both in treatment and in colour, and one may hope that the time may come when they will be replaced by something less offensive to an artistic eye. They might with advantage be moved to the clerestory where they would certainly be preferable to the present windows, covered as they are with a hideous yellow stain.

The central light of the east window was given in 1855, but the other lights were not given till 1874. A comparison of these shows how much stained glass had improved in the interval both in design and in colour.

There are three other stained windows in the chancel, which, fortunately, cannot be seen from the body of the Church.

The large window of the south transept has lately been filled with glass in memory of the Sherwood Rangers who fell in the South African war. It is a pleasant well-coloured window by Kempe, but like many other modern ones, it is inclined to pretty-ness, a word which carries some condemnation in any branch of art. The figures also, are rather inclined to be suggestive of the theatre; all the same, the window is one that may give genuine artistic pleasure.

This is more than can be said of the Foljambe window next to it, which is ugly in colour and ludicrous in drawing. In one of the lights is what is supposed to be a representation of the Israelites carrying Joseph's bones out of Egypt, which seems to be intended to have some reference to the fact that the body of Mr. Foljambe was brought from Pau to be buried in Retford churchyard.

The Mee window next to it, is a good example of the mosaic method by Hardman, rich in colour and good in execution.

Possibly the best glass in the Church is some by Burlinson & Grills, which fills the single-light window in the north wall of the chantry. It represents St. Swithun in an easy yet dignified attitude, his figure being composed of slightly tinted glass on a blue ground, very soft and restful to the eye.

The middle window of the south aisle is by Clayton & Bell, and is a fair example of their work in 1880. The other windows in this aisle should have the same effect on the eye as bad music has on the ear. In the baptistry is an example of Kempe's work, which is considered good by some, but, except in a very strong light, there is a greenish yellow tinge over the whole window which is the reverse of pleasant, and which is the more pronounced because of the different style of the windows near it. It is a common fault of churches to have windows side by side, totally different in their manner of treatment. Even when they are all good individually, the want of harmony in the whole often destroys the pleasure which is always given by unity of design. In olden times, the adornment of a church was in the hands of artists all working with the same ideas and for a common purpose, the glory of God and the honour of their art. In modern days, the artist is rarely consulted, but the work is put into the hands of competing trading firms whose main object is to declare a good dividend. Happily there are signs that this state of things is passing away, and the time is perhaps coming when the best art may again be dedicated to the service of God.

The great west window was put in in 1875 by Clayton & Bell, the colouring is deep and rich, and it is a good specimen of the period.

The west window of the north aisle, and the window next to it in the aisle itself, were put in by George Uttley. He was an inmate of Sloswick's Hospital, and used to come across to the Church to show visitors round. They usually gave him money which he saved until he had sufficient to pay for the window at the west. He then went on collecting for the window in the aisle, and when he had sufficient to pay for two side lights, he put in the middle one at his own expense. The story is an interesting one, and it is to be regretted that the windows have not more artistic value.

The two easternmost windows of the north aisle are fairly good examples of the work of Clayton & Bell.

Details of the windows are given in the appendix.