Cheapside, Early morning—looking down Exchange Alley towards the Market Place. From a drawing by T. W. Hammond, by permission of the Thoroton Society.

My tour of the Market had now brought me back to the neighbourhood of the office. Here, at the upper end of Exchange Alley, the road widened, and provided a space where the market-gardeners were pitched on the pavement and roadway of Cheapside. Their trade was of a semi-wholesale kind, much of their produce being bought by shop-keepers and re-sold. Their goods were arranged on the ground, which was littered with discarded skeps and boxes. Unsold vegetables, straw and other refuse were scattered around, giving the spot an untidily picturesque appearance which attracted many artists. T. W. Hammond, who left a large and beautiful collection of pastel drawings of old Nottingham, came again and again to Cheapside for his subject. He was, for many years, a familiar figure, as he sat at his easel on the pavement or in the roadway, amongst the market litter.

I had now completed, to the best of my ability, the task of recording all that comprised "The Market", and I was walking back along Cheapside in the direction of the Marketplace, by way of the passage known as Exchange Alley. Competent authorities believe that this was in line with one of our most ancient roadways, from East to West. The passage became narrower at its lower end, and here, for a few yards it was arched over, and its entrance was absorbed into the elevation of the Exchange building. Apparently it was not thought possible to divert so old a thoroughfare. A later generation had less respect for it.

About half-way down the Alley, on my right, I came to the heavy, iron-studded door, by which we entered the Weights and Measures office. This was flanked on either side by ladies lavatories, and the entrances were often confused with ours, to the embarrassment of the ladies. On one side was an official convenience, maintained by the Corporation, and properly equipped by the standards of those days. The other establishment was a little shop, four stories high and one room deep, and bearing outside a sign-board with the inscription "Ladies Public Lavatory". The tenant was a decrepit little old woman, who sold a few sweets in the tiny ground floor shop. The sanitary accommodation was a single W.C., reached by a steep and narrow staircase. It was asserted that this was supplemented at busy times, by extra, and more primitive arrangements. At the back of the office, occupying much of the space under the Exchange Hall, were the "Shambles"—avenues of small butcher's shops, many of them without any access to daylight or ventilation. This was actually a meat market, though not under the control of the Markets and Fairs Committee. Nevertheless, it was very familiar ground to me. The name 'Shambles', was, of course, a link with earlier times, when slaughtering, as well as selling, was done on the site. There had been a time when nearly all the meat trade of the town had been carried on here, but though it still flourished, its importance had considerably declined.

Standing at the office door, I looked on a curious block of property, an island site, sandwiched between Exchange Alley and the street beyond, and having entrances from both. Almost opposite, with its narrow frontage projecting up Cheapside, was a boot shop, known to all as the "Shoe Booth", a name surviving from the time when the site was covered with temporary structures. Next to this, and exactly facing the office across the narrow passage, was the "Birdcage Vaults", referred to earlier as the source of supplies of bread and cheese. It was a curious place, consisting of one room and a cellar. It was entered, down two steps, from Exchange Alley and had an opposite entrance on Cheapside. It was always a mystery to me how the business of a publichouse could be carried on in such a restricted space. There was, however, ample room for storage in the cellar which adjoined ours. As may be imagined, our surroundings supplied a variety of smells, which we had to tolerate as the natural atmosphere in which we worked. It was not improved by the naked gas jets, which were the only means of lighting.

Our office was part of a block of buildings known as "The Exchange", whose kitchen premises were immediately over us. The building faced the Market place, and included the Exchange Hall, where the Council Meetings and civic functions were held. Behind this was the Mayor's Parlour, and the residence of the Mayor's Sergeant. Whenever I had the chance I used to go into the Council Meeting, sitting in the public seats at the back. I was greatly impressed by the dignity of the great men of the time—Sir Edward Fraser, leader of the Liberals, (then the predominant party), Sir John McCraith, Conservative leader, and Sir Samuel Johnson, Town Clerk. These were men of culture, to whose speeches it was a joy to listen. The Labour party was then represented by one councillor, named Gutteridge. Some years later he was joined by a young man named Herbert Bowles, some of whose first halting attempts at public speaking, I heard.

By the time I had become familiar with my surroundings, inside and out, I had also a general idea of the work of the office, and had taken over all the clerical work. There were many things which we now regard as essential, that we did without in those days. We had neither typewriter nor telephone, and I cannot remember any method of filing letters or documents. Occasionally, a letter which I wrote would be thought of sufficient importance to copy, and I did this in a copying press, which was our only mechanical aid to business efficiency.

A welcome change in my work occurred when I was taken out by one of the Inspectors to learn the work of outdoor inspection. Sometimes we visited shops, street by street. I helped to carry the standard weights and balances, and to set them up on the shop counter. While the Inspector was making the tests, I was noting down name and address, and anything else which had to be recorded. I was shown that it was advisable to examine the scales immediately on entering the shop. Unscrupulous traders were more common then, and it was not a rare thing to find a piece of fat, or some sticky substance, attached to an unseen part of the scale. Nothing was ever stuck on a weight. The outdoor work which I liked best, was assisting in what was called 'heavy' inspection. For this, we had a horse and cart, and we carried a ton of 56 lb. weights and a few tools. We visited railway depots, collieries, gas works and other places where large weighing machines were used. The weights were lifted out of the cart and in again many times in the course of the day, by two strong labourers. I was shown how a weighbridge, capable of weighing 10 or 15 tons, could be tested for accuracy by the use of only a ton of weights, and I saw many interesting things on our visits to colleries and other places. There were no weighing machines below ground, but I was once taken down a mine as a visitor. I looked forward to our yearly visit to the prison, where we went at the request of the Governor. The prison authorities insisted that the weighing of prisoners' food should be accurate. We timed our round of the premises so as to arrive at the kitchen at noon, when the prisoners' dinner was sent out. This usually consisted of a tin panikin of rich vegetable soup and a small loaf of brown bread, just out of the oven. We always had a prisoner's dinner ourselves, and a very savoury and satisfying meal it was. All the kitchen work was done by prisoners, probably 'good conduct' men. On this day we were each 4d. in pocket. Heavy inspection took us a long way from the office and transport facilities were few. We were therefore given a lunch allowance of 4d. which we generally spent in a pub, on bread and cheese, pickles and a drink. Many of my recollections of those days have to do with food: I was a growing lad!

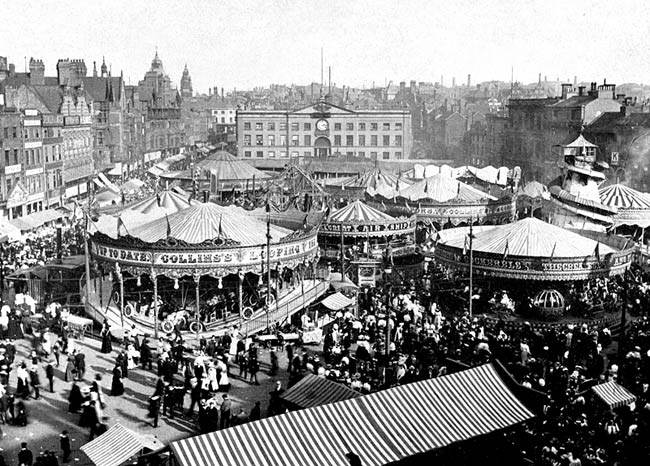

Goose Fair in 1908.

When I had been at the office a few months, a big event began to be talked of—Goose Fair. Soon after midsummer, letters began to arrive from all over the country, making application for sites for shows, round-a-bouts and stalls. Mr. Radford took a great interest in these, and I remember his method of replying to applicants. If the applicant did not enclose a stamped and addressed envelope, he got no reply. When the envelope was forthcoming, Mr. Radford tore the fly leaf from the letter, or used any scrap of paper which was handy, and wrote, "Granted, J.R." That was all the reply which most of the applicants got; but it satisfied them. A few of the more important people received a brief letter. Letters of application which were "granted"' were filed by the simple device of folding them in a bundle, secured by an elastic band. Later, the bundle was sorted, and divided into a number of smaller ones, representing different parts of the fairground. Shortly before the Fair, a rough plan in pencil was prepared, showing the position, more or less, of the larger attractions,—the riding machines and shows.

On the Monday of Goose Fair week, the staff, with some casual assistants, assembled at the office at 6 a.m. We first partook of a substantial breakfast of ham sandwiches and tea. Then, six of us went out into the empty Marketplace, carrying buckets of whitewash, brushes, tape-measures and lines and large lumps of chalk. Positions were found by the use of tape measures and the outlines of the pitches were brushed in with whitewash. In a few hours, the Market, clear of stalls, was covered with white circles and rectangles.

Next morning, Tuesday, the show people began to arrive with their wagons and trucks, drawn by traction engines or by horses. In some miraculous way they got into their positions without collisions, and quickly began to erect their properties. Most of the riding machines were the old galloping horses, where the whole machine, platform included, revolved on its axis. They were driven by steam engines. A new kind of machine was coming into use, which, later on, ousted most of the old ones. This was the switchback type, with elaborately carved and gilded cars, simulating dragons, peacocks or whales, riding on a railed track which ran up and down hill. These, too, have been superseded by others, but the old galloping horses round-a-bouts have survived all the changes.

While these preparations were going on, shows were also being built up. The largest of these had outside stages built on wagons. The performance took place on a stage built up at the back, with living wagons conveniently placed to provide dressing-rooms. The show was enclosed bv a wooden framework covered with canvas, with shutters extending 4 or 5 ft. from the ground, at the rear. There was some seating accommodation at the front, but much the larger part of the audience stood on a sloping floor. The smaller shows were only canvas booths with fronts of painted shutters or canvas 'flashes'. The shows I remember most clearly were Wall's Phantascope and Lawrence's Marionettes. The proprietor of the first was a jolly, fat little man, who gave short melodramas, concluding with a ghost illusion, worked by mirrors. His show faced the bottom of Market Street. Lawrence gave quite a good marionette show, but the best of his entertainment, like that of all the big shows, was given free on the front stage, to attract the crowd. The small shows consisted of freaks—human and animal— illusions, conjuring and second sight. One show of medium size, stood out amongst the rest—Professor Burnett's Boxing Academy. An imposing array of "bruisers" was lined up on the small outside stage. Inside, these artistes gave exhibitions of their skill, with each other, and challenged local talent. There were no cinemas at my first two or three fairs. They arrived a little later, and it is interesting to remember that the first public exhibition of films was given on the fairgrounds of the country. I remember how crude they were, but they rapidly improved, and 'living pictures' took the place of the old entertainments in all the big shows. The change over was accompanied by the general use of electricity and the show fronts became a blaze of coloured lights. The riding machine owners followed suit and decorated their properties, especially the great mechanical organs, with thousands of lights. Fairground cinemas did not have a long life. They could not compete with permanent cinema theatres which came into being, and the general decline of shows dates from this time. Their place on the fairground was taken by new and more elaborate riding machines.

By the Wednesday of Fair week, all the big concerns were built up, and it was the turn of the stallholders to take up their positions. I spent many hours with Mr. Radford, carrying a tape-measure, jostled by a crowd of importunate people, the owners of coconut shies and games. A number of them secured places along the sides of shows and in various odd corners. Many were turned away after following the "tober-men", as they called us, for hours. When we returned to the office, as we did occasionally, they waited patiently outside, to resume the pilgrimage when we re-appeared. We spent a lot of time marking out the positions of stalls in the streets surrounding the Market. Most of these were occupied by market tenants who were dispossessed of their usual sites. The streets all round the Market were lined with stalls, narrowing these thoroughfares to half their usual width. An unbroken line stretched the whole length of Long Row and Chapel Bar, from Clumber Street to Derby Road. They were stocked with gingerbread, brandy-snap and sweets. Quantities of savoury delicacies,—hot peas, chip potatoes and shell fish,—were also sold, and there was a wonderful array of novelties, toys and dolls of every description. Some market people had to go further afield. Nurserymen were placed on both sides of Market Street, and country-produce dealers in Victoria Street. Wholesale traders were moved into Parliament Street, there being no separate wholesale market then.

So we came to Thursday, the opening day of the Fair. Early in the morning, barriers, consisting of barrels filled with sand, were placed across all the roads leading to the Marketplace, and traffic, during the three days had to find its way round by other routes. The great sensation of the morning was the arrival of Bostock and Wombell's Menagerie, the biggest show in the Fair, and the last to arrive. It had then been on the road for nearly a century. It approached the town by Derby Road, and Chapel Bar, and moved on to the large triangular space reserved for it in the western end of the Marketplace. The show was made up entirely of large wagons, one side of each being enclosed with iron bars, over which shutters were fixed when the Show was travelling. The cavalcade of wagons, drawn by fine horses, with a couple of elephants and several camels bringing up the rear, was watched by hundreds of excited children. On arrival at the site, the wagons were lined up in their appointed places. If a wagon was slightly out of line, an elephant, instructed by its keeper, placed its head against the side, and gently pushed it into position. All the morning preparations went on. Wagons were fitted up as pay boxes and living quarters for the proprietors. More wagons, with folding wings, formed the stage front. At last the canvas roof was stretched across, supported down its centre by tall poles. The shutters in front of the animal cages were let down on their hinges, and the show was ready to open. It was, for its day, a fine collection of animals in surprisingly good condition, considering the cramped quarters. There were performances with lions and tigers, sea-lions and seals, and an 'educated' chimpanzee. When the show was not tod crowded children were given elephant rides, and often there were baby animals which privileged visitors were allowed to nurse. On the front of the show was a uniformed brass band, and leather-lunged 'barkers' announced the wonders to be seen within. A negro lion tamer showed himself between his performances, and an ancient pelican surveyed the scene with jaundiced eye.

All was ready for the opening of the Fair at noon on Thursday, but, in my early days, there was no opening ceremony. The Clerk of the Markets raised his walking stick, and, at the signal, the organs blared, the wheels turned and the fun began. It was Goose Fair!

The second day, Friday, was children's day, it being a little less crowded. All classes patronised the Fair. Only a very few of the townspeople kept aloof from the popular festival, and as more and more special trains arrived, the crowds grew and congestion increased. Local families entertained relatives and friends from a distance, at the annual family re-union; and the giving of Fairings—large and small presents bought in the Fair and the town—was a general custom. My task on the Friday, was to assist in collecting the rents from the showmen and stall-holders. There were no defaulters, because everybody was so anxious to come again. Later, I and others, mixed among the crowds, collecting the coppers charged to the hundreds of hawkers, for the privilege of carrying their "trays" loaded with tiny toys, novelties and sweets for sale. They were given badges to wear, indicating that they had paid their quota.

The climax was reached on Saturday, when from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. everything was in full swing. As the crowds thickened, the prices charged for rides rose, but still the rush to mount the steps of the round-a-bouts did not slacken. My strongest impression is of the surging crowds moving ceaselessly round the Fair. It was impossible to change one's direction once one was in the stream. Gangs of young people, and some older ones, formed "crocodiles". Linked together by arms on the shoulders, or round the waist of the person in front, they forced a passage through the crowd. Beastmarket Hill was famous for this amusement. All but the most vigorous shunned the narrower avenues of the Fair, knowing that they would most likely be lifted off their feet and be carried along bodily by the throng. Many found this thrilling, but it could be alarming. Big policemen stood here and there checking the exhuberence of boys and girls when things became too rough. Little brushes, known as "ticklers", and rubber balls which squirted water, added to the excitement, until they became so much of a nuisance that they were banned. Games of skill were popular and there was keen competition at the coconut shies. Rows of grotesque figures, known as "Emmas", could be knocked backwards by a well directed blow from a wooden ball. On the show fronts dancing girls, clowns and jugglers gave a free entertainment to crowds, which presently surged into the show eager to see the performance. How the older people, who lived within hearing, endured three days of blaring organs, shrieking whistles and cries and laughter of thousands of excited merrymakers is a puzzle. They just had to put up with it, and did so usually, with remarkably good grace.

With dramatic suddenness the Fair came to an end. At the stroke of midnight on Saturday everything stopped, and a moment of thrilling silence followed the din. It was my job to go round the outskirts of the Fair, with a police whistle, and to stop any riding machine which had not pulled up on the stroke of the Exchange clock. The lights went out, and the last ride was finished in darkness. The crowds melted away and the tired show people retired to their living vans for a meal and a very short rest. Then, in the darkness, relieved only by a few flare lamps, they began to dismantle their tackle. Right through the night they worked, as it was an inflexible rule that the market square should be completely cleared and cleansed by Sunday morning. When the showmen moved off, an army of scavengers turned out to cart away the enormous amount of rubbish. I recall a later year, when fifty cart-loads of confetti were swept up and taken away. By that time, it had become such a nuisance that it was forbidden. The sweepers alwavs made a little haul of coins, dropped among the rubbish—mostly copper, sometimes silver, and, on rare and refreshing occasions, gold. When ladies in Sunday apparel, accompanied by silk-hatted gentlemen, set out for morning service, all traces of the Fair had vanished; the Marketplace was empty: the side streets nearby were cleared of the scores of living vans which had been standing there; but on the site of the menagerie, there lingered the unmistakable odour of animals.

At my first Goose Fair, I made the acquaintance of many showmen, some of whom became my very good friends. I marvelled at their living-vans, where, as the years went on, I often enjoyed their hospitality. Many of these were very costly, and were fitted with every comfort and convenience possible, and with considerable luxury. They were elaborately and expensively decorated, and panels of plate glass and mirrors were fixed in every possible place. They glittered with silver-plated metal-work. They were clean and well kept, and the women were extremely houseproud. I found the showmen generally hard-working and self-respecting, though, from the nature of their business, they had to be tough, and generations of hard-living and a certain amount of oppression in official quarters had made them jealous of their rights.

As a youngster of sixteen, I naturally entered into the preparations for Goose Fair with enthusiasm, and enjoyed the three days of novelty and excitement. From 1904 onwards I took entire charge of the Fair. As successor to Mr. Radford a few years later I did not adopt his "badge of office", —the gold hat-band embroidered with the title "Clerk of the Markets," which he wore round his silk hat; but I still have it as a memento of those days. I was a very young man to assume such responsibility, and some amusing things happened when Fair people came to the office and asked for the man in charge. When I appeared, I was told that it was the boss they wanted, not the office boy. For more than forty years I organised the Fair, and I have witnessed and assisted in many changes, including removal to the new site on the Forest. Looking back, I recall most clearly those early days in the old Marketplace, and I can still smell the mixed odours which pervaded Exchange Alley, and which, on Goose Fair Saturday night, were of almost unendurable pungency. For many years I spent the whole of that night in the Marketplace, and the drama of the midnight climax is still a vivid memory.