The screen from the Choir.

We now pass under THE SCREEN (1340—Decorated). There are curious little staircases in the north and south walls. Notice three prebendal miserere stalls on each side of the central archway. They (the miserere) Were of old used during long services to lean against. If you turn up the seat, you will find considerable rest and comfort from the support it gives while you are apparently standing in front of it. The third, on the north side is “Oxton,” William Talbot’s stall, and he is buried beneath; you can see the slab that used to lie over his grave in the north wall of the Choir Aisle. He was a light in dark days struggling to maintain amongst the Canons a high standard of holy living in a very degenerate age, and his simple epitaph, doubtless composed by himself, shows the humility of this truly great man. I give the translation :

“Here lies William Talbot, wretched and unworthy priest, awaiting the resurrection of the dead under the sign of the cross (1497).”

Talbot's Tomb.

When we think of the great and noble monuments Southwell once possessed, how strange that this epitaph announcing “wretchedness and unworthiness” should have attracted more notice than them all, and should have outlasted every other.

The Bishop’s Stall has beautiful diaperwork at the back. It is most interesting to reflect that during the summer of 1530 Cardinal Wolsey usually occupied it.

Turn east and look at the CHOIR.

The Choir looking east.

1230—1250. Early English. Very beautiful interior built by Archbishop Walter Grey. There are six great arches, the piers of which have clustered shafts, all of which are keeled. The roof was built last of all about 1250; it is curious how the centre groin, both in the great east window and the smaller aisle east windows, is brought down to a small pillar between the lights of the east windows.

The lower part of the great east window contains old painted glass wonderful for its colouring, brought by Mr. Gaily Knight from Paris, where he discovered it (1815) in a pawnbroker’s shop. It was once in the chapel of the Knights Templars, and must have been almost the last thing that the unfortunate Marie Antoinette looked upon before she was led out to the guillotine, as she was imprisoned in this chapel. The first light from the north end represents the Baptism of Christ; the lower portion of this, and some of the glass in the other pictures, is modern.

The second depicts the Raising of Lazarus, and in it we discover King Francis the First of France in a crimson cap. In the third light is Christ entering Jerusalem; the sturdy figure of Luther will easily be discerned close to the Saviour's side; Louis XI. is there in his usual blue hat; the Duke of Orleans bears him company, just beneath, in a cap of yellow. The fourth light is the Mocking of Christ, and into this Dante is introduced, not the usual profile we know so well, but a full face likeness.

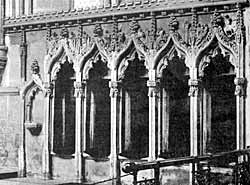

The sedilia.

SEDILIA (1350), five seats for the clergy on the south side of the Sacrarium. Southwell is unique in having five. Generally, sedilia have only one, two, or three seats. This may be owing to the peculiarity of her foundation. Since all her Canons were equal in rank, all would expect, when in residence, to occupy positions of the same distinction.

Notice the diaperwork and the figures above representing the story of the Creation and the Redemption, half of the space being given to each subject. The subjects are as follows—(i) God the Father with the World in His Hands; (2) and (3) have been broken away and are filled up with modern figures; (4) Joseph's Dream (Joseph is generally represented as leaning on his staff), “Fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife, for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost”; (5) The Nativity; (6) Flight into Egypt.

LECTERN (1500). A fine brass eagle formerly in the church at Newstead Abbey. The poor monks threw it along with their plate into the lake there to hide it from the grasping hands of Henry VIII. There were some curious old deeds concealed in the hollow of the ball. The inscription round it is in Latin, “Pray for the soul of Ralph Savage, and for the souls of all the faithful departed.” It was given to Southwell by Sir Richard Kaye in 1805. The plate has never been recovered.

Spandrel in Chapter House.

CLOISTER (1280). As you pass through a beautifully decorated doorway in the North Aisle you enter the Cloister, or Vestibule. Notice the arcading of the walls, it is very lovely; instead oi the usual wreath round the capitals, the design of each capital is continued in a straight band along the thickness of the wall, and finishes up round the outside corresponding capital. The Cloisters were originally unglazed; the glass was put in later on as a protection from the weather.

On the west as you enter the door look up, and you will see the “secular” priest shaking the “regular” monk by his tonsure. The “seculars” had literally (as well as figuratively) the upper hand in Southwell.

In the thirteenth century I fear that reverence for holy things and places was not always one of their characteristics, and while they loved their own aggrandisement, there was by no means the same amount of pious zeal expended on the spiritual interests of those committed to their care.

Southwell was always a “Collegiate Church” of “Secular Clergy” as distinguished from the “Regular Clergy” who lived together in monasteries.

The Secular Clergy were the Parochial Clergy of those days; they were, however, generally banded together in colleges, as at Southwell, with a rule of life. The idea of a “monk” was to save his own soul; that of a “secular” priest to save not only his own soul but the souls of others. It was a splendid idea and a marvellous system, working well for centuries. England owes much to such foundations, as they kept alive the spirit of throughout the country. The Church is now both a Cathedral and a Parish Bishopric was founded in 1884.

To return to the Cloister, on the east side is a quaint little court, and in the middle of it you will find a W cut in the pavingstone which covers the opening into the “Holy Well.”

Chapter House archway.

Capital in Chapter House.

We now come to what Ruskin calls “The gem of English architecture”—the CHAPTER-HOUSE (1285—1300). Decorated. The high roof outside was restored 1881). This is the latest and the loveliest of the Cathedral buildings. It is very like York, a little earlier perhaps, but much smaller, and I think we may say more beautiful. York may have been copied from it. Truly of this, rather than of York, should it be said, “It is among Chapter-houses as the rose is amongst flowers.” There is no central pillar, its form is octagonal, nothing can surpass it in beauty, all its ornament is from natural foliage, and the grace and lightness (to say nothing of the wonderful undercutting of the wreaths and floriated capitals) is simply marvellous. You feel that the workman who did it must have been inspired—a consummate artist, and no mere copier.

Mr. Loughton has chosen the best point of view in his excellent photograph. The exquisite doorway, in itself so lovely, makes a perfect frame for the fairy-like architecture beyond.