< Previous | Contents | Next >

Beauvale

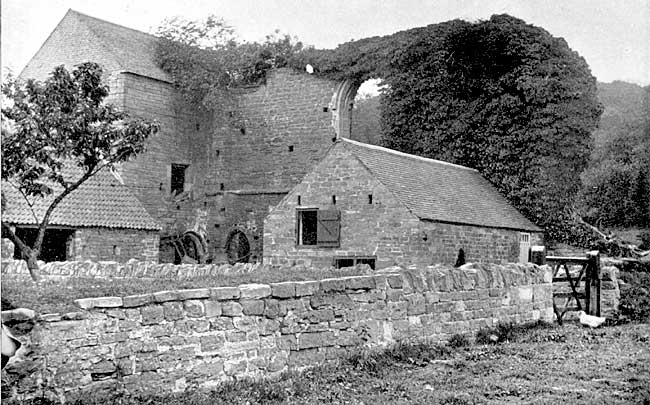

Remains of the church wall at Beauvale Priory.

This name was not known in Greasley until Nicholas de Canteloupe gave it (not to the hamlet but) to the Priory which he established there. Until then it was part of the Park of Greasley. The adjoining wood still bears the name High Park. The hamlet has subsequently acquired the name from the Priory, but the appellation has been sadly corrupted. The original name which de Canteloupe gave to the Priory was Bella Vallis. The Carthusians, coming probably from their mother house near Grenoble, frenchified the name into Beau Vale. Subsequently the last letter, e, which is not pronounced in French, was given expression to in English. From thence, as an earlier ordnance map shows, it was called Bevale, and in another Beaver, and at last the beautiful vale came down to Beggarlee. We would plead with all whom it concerns to restore to that charming and still romantic part of our parish the name which properly belongs to it, which surely in our days of boasted educational progress and advancement is not too much to ask, as a slight lesson in refinement.

We have already in an earlier part of this book given an account of the foundation of the Priory, which Dugdale, in one instance, calls not only Bella but Pulchra Vallis. It was the youngest establishment of the Carthusian Order in England, and the last founded Monastery in our County before the Reformation. The monks came from their mother house in France, and it is not unlikely that Nicholas de Canteloupe met with them there, or at least with the repute of their sanctity, which would have been sufficient to him to select that Order rather than another for his Monastery. He had no doubt knowledge of other Orders in England, both from his own observation and from his family relationship with high ecclesiastical dignitaries, and it may be that he was by them influenced, as well as from his own inclination, to give the Carthusians a preference over other monastic brotherhoods in his selection.

De Canteloupe will first have made some temporary provision for his prospective monks before he invited them to come here. We have seen what he did for them to establish them at Bella Vallis, and we presume that he was not disappointed in them, even though later on they did not disdain to secure some additional property by the backstair of using for it the Rector, or rather Vicar of Greasley, which as we have seen in Watnall, was forgiven them. According to the rule of their Order the monks were twelve in number, with the addition of some lay brethren, and probably some menials. Their number however was later on slightly increased, owing probably to conditions arising from some of the benefactions which were bestowed on their establishment. To the inhabitants of Greasley and the neighbourhood they were probably, so far as teaching is concerned, of no great benefit, because they did not profess to do that; but the reputed sanctity of their lives spoke volumes for them, and their sacred seclusion will have told on the common people with a religious awe. Besides, the Lords of Greasley might now and then be away on important business of the King, but the Charterhouse was always here and their direct or indirect influence was ever felt. And so the Monastery of Beauvale continued for nigh two centuries, and except for the sound of the holy chaunts, which ever and again broke from the sacred confines within to the world without, there was perpetual silence within those walls. The monks had each their separate cell of small chambers, which they never left, except for their religious exercises in their church and vigils, and possibly too (though that was properly the occupation of the lay brethren) for some work pertaining to the cultivation of their lands. It is generally admitted, that the monastic orders were great agriculturists, and that they made their surroundings to smile in Nature’s beauty. So far as Beauvale is concerned it was without the aid of man a lovely and romantic spot, much of the picturesque beauty of which still remains, and meets the eye of a thoughtful visitor with surroundings of soothing influence. But the hallowed structures of the past have nearly all disappeared. The ruthless hand of grasping vandalism has left nothing remaining that could be turned into cash, and there are now but some poor ruins of the long dismantled and once noble sacred pile. Must we add, alas! that the common people learned to copy their betters and to follow their deeds, until the irony of fate would have it, that parts of the broken pillars and capitals of the arcades of the Church should now be met with in cottage yards to serve the people as tub stands. We need not dwell on how the Priory was dismantled to become a ruin.

A visitor to our locality, who, in the month of June, 1891, wrote some brief and interesting articles about Greasley under the nom de plume “A Pilgrim,” could not help quoting the appropriate passage from Dr. Neale’s poem:—

Ill hands are on the Abbey Church,

They batter down the nave,

They strip the lead, they spoil the dead,

They violate the grave.

They overthrow the altar tomb

With effigy and lore;

For Jesus’ tender love, in peace

Repose they evermore.

We sometimes now stand on that erst consecrated spot, and we cannot shake off the feeling which comes over us, that notwithstanding all that we cannot agree with of the past, we are still standing on holy ground, at whose voiceless whispers it is, as though we heard: “ Take off thy shoes.” The Almighty, who is everywhere, is here. The place is not God forsaken. Stop and pray!

Yes, and if we may not join in the chants of the past, we can surely send a devout thought and sigh up to Him who directs all things, and reflect that, however mistaken, yet holy men lived and prayed here, some of whom may in their solitude, like Luther, have found their Saviour and His full and free salvation.

The church wall and farm buildings at Beauvale Priory.

The Carthusians do not seem to have been much in favour in England, which was probably owing to the severity of their rules. Among other their garments were coarse, their bed was hard, their fare was a frugal vegetarian Lenten one for ever, and their whole monastic life a complete selfabnegation and self-sacrifice from all the world without, with perpetual silence in the world within their walls. But the time had come when their chaunts of the versicles from David’s holy psalms should no longer send their echoes from pillar to pillar, and from the archades to the vaulted roof. It was not that men had become so callous as not to suffer them elsewhere, but the material value of the monastic establishments had whetted men’s cupidity. The monasteries must fall. The pretence for their spoliation was awowedly the Reformation, the origin of which in the bluff monarch’s time was none of the purest, but besides that, the lives of some monkish communities had given their enemies a strong handle. To the honour of the Carthusians it must be said, that their memory was never thus asperged. They never like some other communities, departed from their severe rules of life, even though their establishments emerged from comparative poverty to apparent opulence: but Henry VIII. could not get the Pope’s decree of dissolution of his marriage with Katherine of Aragon. He therefore broke with and repudiated him, and the Parliament in 1533 decreed the acknowledgment of the monarch as head of the English Church, and required the transference of allegiance from the Pope to the King, while the King himself had sent forth an edict for the spoliation of the monastic orders. The edict was naturally resisted by the religious orders, and possibly more loudly so by the Carthusians. The Prior of the London Charterhouse at that time was Houghton, to whom Augustine Webster, the at the same time Prior of Beauvale joined himself in what we probably now would call a constitutional agitation; but that was their mistake, and they did not sufficiently know the temper of the monarch with whom they had to reckon. It appears, moreover, that they had gone a step further, and that they had firmly declined to change their allegiance, and that was enough for their times. They were charged with High Treason, and together with three other Carthusians, with superadded barbarities executed at Tyburn on the 4th of May, 1534. Mr. Cornelius Brown, mentioning this subject writes that Sir Thomas Moore, whose daughter (Mrs. Roper) was present with him, saw the Priors from his prison windows being led to their sufferings and said to her, “Lo, dost thou see Megg, that these blessed fathers be now as cheerfully going to their deaths as bridegrooms to their marriage?”

This is said to have been the first blood which Henry VIII. shed in connection with the spoliation of the monasteries; but it is probable that he hoped thereby to bring others to submission. He may, besides, have had some early intelligence (however partial) of a strong hostile movement which was preparing against him. It was as yet immature and secret, but it in reality became in its issue a severe test of the stability of Henry VIII’s crown. The movement was called “The Pilgrimage of Grace,” of which Mr. Stevenson, in his Bygone Nottinghamshire, gives a telling account. The revolt broke first out in Lincolnshire, but soon spread throughout Yorkshire and the north. Both nobles and ecclesiastics rose against what they conceived to be threatening their enslavement; and the partisans of the movement took the “Five Wounds” for their badge. The whole northern country had soon risen, and mustered not less than 30,000 well horsed men, so that about half the kingdom was nearly lost to the King. Henry VIII’s Privy Seal was at that time one Thomas Cromwell, who from an humble extraction had risen to the high position (which Cardinal Wolsey had held) of Privy Seal and Vicar-General of England. Sycophant as he was, and a man of subtlety and craft like some others, he had so gained on his royal master that he was permitted to rule the kingdom with a rod of iron. Though the danger from the general northern revolt was great, yet this wily man did not lose heart over it. He bided his time with cunning patience, and even made it appear that he yielded, by allowing Norfolk, who had only 6,ooo men, to treat with the leaders of the rising. Alas! for the peace which was then arrived at. The Insurgents were offered and accepted the assurance of a free pardon, and the promise of a Parliament at York, and with that they disbanded and returned to their ordinary peaceful avocations; but they lived in turbulent times, when some petty disturbance or another might easily occur which actually took place. That was Cromwell’s time for his vendetta. He took advantage of the occasion. He recalled the settlement which had been arrived at. He threw off the mask, and shewed himself the vindictive creature which in reality he was. The country was soon filled with gibbets on which the leaders of the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace, together with their adherents expiated their too easy trust in Cromwell’s assurances. The whole nobility of the north were implicated in the rising which had taken place, and alas in the betrayal too, from the too easily accepted promise of a free pardon and of a parliament at York. Cromwell’s vengeance was terrible. Lord Dacre of Yorkshire and Lord Hussey of the Lincolnshire aristocracy, the Abbots of Barlings and of Woburn and Sawley suffered in Yorkshire; while the Abbots of Fountain and Jervaux were hanged together with the Percy’s at Tyburn. Lady Blumer was burned at the stake, Sir Robert Constable was hanged in chains at the gate of Hull, and some of the last to suffer were the Prior of Lenton with some of his monks, who died on Gallow Hill. But there were yet three more sufferers, who Mr. Stephenson says were the last, i.e., Henry Leatherhead Vicar of Newark, who was arraigned at York as late as in the year 1538, and executed along with Thomas Mimer, Lancaster Herald, and Morley a monk of Fountains. Such was the bitter ending of the Pilgrimage of Grace, of which possibly, or even probably, the Priors of the London and of the Beauvale Charterhouses were the early and unfortunate forerunners.