< Previous | Contents | Next >

And if aforetime, as we know was often the case, our ancient kings and princes sallied forth with their noble retinues from the castle of Nottingham, or from their palace of Clipston; or if later, as in the case of James I., and of his ill-fated successor the first Charles, or of William of Orange, from Rufford or Welbeck to follow "the branchy-headed stags :" so in our own day also, the hunting field of this district has not been without its royal visitant, having been honoured by the presence of the heir to England’s throne, when the present Prince of Wales was, in the year 1861, on a visit to the late-lamented Duke of Newcastle, at Clumber.

With respect to the forest at large indeed, the glories of old Sherwood have departed, both as regards its vert and its venison; though very consider-able portions of both these sylvan riches are preserved in the parks of the neighbouring nobility and gentry. Instance at Welbeck, Thoresby, and Rufford, where goodly herds of deer and many a noble oak, some of which may have seen the days of bold Robin Hood, are still to be seen. Yet of what constituted the forest in general, it can no longer be said, in the language of a noble bard of its own, who here clearly drew his inspiration from the ancestral home of his youth, to be

"Crowned by high woodlands, where the Druid oak,

Stood like Caractacus, in act to rally

His host, with broad arms ‘gainst the thunder stroke,

While from beneath his boughs are seen to sally

The dappled foresters—as day woke

The branching stag swept down with all his herd

To quaff a brook that murmured like a bird."

Byron.

In these respects, over the forest at large, "Ichabod" is inscribed in legible characters. A bit of the real old Sherwood, however, still lingers in the remains of Birkland and Bilhagh, near Ollerton and Edwinstowe, and truly beautiful it is, vividly recalling the memories of the olden days. To the lover of nature, and especially to the admirer of sylvan scenery, nothing more delightful can well be imagined than to spend a summer’s day amidst its sunny glades, or under the shade of its venerable oaks. To such, one would say, in the language of our immortal bard, (himself no small lover of vert and venison, albeit, unless he be sadly maligned, in a somewhat illicit way,) in that sweet creation of his fancy, "As You like it,"

"Under the greenwood tree,

Who loves to lie with me,

And tune the merry note

Unto the sweet bird’s throat,

Come hither, Come hither, Come hither."

The Forest had also in its midst two monasteries, the Abbey of Rufford and the Priory of Newstead; while at its extremities were the Abbey of Welbeck, the Priory of Worksop, and the Abbey of Lenton; the last of which was endowed by King John with the tithe of all his venison in the counties of Nottingham and Derby.

The monastery, however, which was peculiarly that of the Forest was Newstead, or as it was termed "Monasterium de Novo Loco in Shirwood." This was a royal foundation, established by our second Henry, about the year 1170, for canons regular of the order of St. Augustine, and endowed by him, not very richly, with the site of the Priory and the surrounding district, together with the adjoining vill of Papplewick, the church, and the mill thereof, which the canons had made. He also gave considerable property in Scepwick and Walkeringham. He further granted to the canons freedom from all land and secular services, and exemption from toll and custom throughout England.

Among the early benefactors appears Robert de Caux, the forester of Sherwood; and of later times, viz. 15th Edward III. a charter is extant of two brothers of a truly forest name, Henry and Robert de Edwinstowe, clerks, granting to this convent the whole manor of North Muskham, on condition of the finding of two chaplains to celebrate divine offices for ever, daily, in the church of the Blessed Mary of Edwinstowe. This document is witnessed, among others, by other forest names, such as Adam de Everingham, Lord of Laxton, descendent of Robert de Caux, and Thomas Longvillers, knts., Robert de Calveton, Hugo de Normanton, and others.

To this retired monastery we have evidence that our early monarchs who, after their fashion, were men of piety, no less than of violence, often resorted during their visits to their favourite hunting ground of Sherwood, and during their sojourn at their palace of Clipston. And surely we may hope that amidst the sylvan solitudes, far apart from the pride and circumstance of glorious war and kingly state, in this quiet habitation dedicated to religion, their proud and violent nature may have been somewhat toned down and softened, and their thoughts led to seek a kingdom not of this world. Even the very convent bell, while calling to early matins and rousing from his lair the gallant stag, may, we may well suppose, have .struck into the heart of bold Robin, whose name is still preserved in the neighbouring hills,—his former resort,—and into the hearts of his associates and followers, some sense of religion, and caused them to pause for a moment in their lawless career.

Thus we may hope, this retired royal foundation may not have been altogether without its good effects, suited to the age in which it flourished, till it fell with other similar establishments in the reign of Henry VIII. Its revenues, spiritual and temporal, were then valued at £289 18s. 82 d. per annum.

It was shortly after, namely, 27 May, 32 Henry VIII. granted it to Sir John Byron, Knt. of Colwick; in which family it continued till it was sold by its most renowned possessor of wide-spread poetic fame to Colonel Wildman, and after his death to its present possessor, William Frederick Webb, Esq.

The monastic remains are still considerable here; a residence having been formed, by the Byron family, out of the Priory buildings. These are chiefly arranged, as usual, around a cloistered court, on the south side of the nave of the church. The allies of the cloister are still preserved, and form communications to the different parts of the house, their outer walls having been raised, and passages made above to the upper apartments. On the east side is the chapter-house, now used as the chapel of the establishment. It is a beautiful structure, divided by piers, and entered by a very fine lofty Early English doorway; which has a circular head, enriched with a floreated wreath, and having banded nookshafts.

To the north of this is another plainer pointed portal, now closed, which has led into a passage or vestry adjoining the south transept of the church, which yet remains, and is incorporated into the house; and now alas! converted into a billiard room.

The north alley of the court occupies the usual place of the south aisle of the nave of the church, which seems always to have been deficient in this member. At the western end of this alley is a plain doorway, now closed, which has formed an entrance into the church, from this quarter. Here, it is probable, was the Prior’s lodging, this being a usual site of that appendage of Augustine houses, as was the case at Bridlington and Worksop. This building, standing upon an undercroft, divided by a row of columns still remains, though it has been considerably altered in the time of the Byrons, and extended southward, with the addition of a tower at its south end, since their days.

On the south side of the court was, no doubt, the refectory. the entrance doorway of which may be observed near the west end. This room seems to have been placed parallel with the cloister alley. To the east of this would be the kitchen department, which still preserves much of its ancient site. Over this part extensive modern buildings have been erected, containing some of the finest rooms in the house, which is replete with objects of interest, especially with relics of its illustrious poetical Lord.

With the exception of what has been already mentioned, nothing remains of the body of the church, but the west front. It appears, however to have been a structure of large dimensions, and it seems that the choir extended as far as the monument, still remaining, which the poet erected to the memory of his dog, "Boatswain." This, it is probable, occupies the place of the high altar; the cynical bard, as it seems evident from the tenour of the inscription, intending thereby to indicate that his dead favourite was more worthy of interment in that place of honour than the great ones, who usually are laid there. The bones of one of the latter, indeed, he is said to have disinterred, when making his dog’s grave, and caused the skull to be formed into a drinking cup, mounted with silver, and bearing the inscription, to be found among his "Occasional Pieces," beginning with

"Start not, nor deem my spirit fled."

This relic of mortality was long exhibited here; but has, by the present owner from a very proper feeling, been consigned again to a quiet restingplace within the precincts of the abbey.

The west end of the church is nearly perfect, and is a structure of very great beauty. It is divided by buttresses, which have niches, and are richly supplied with canopies and crockets. The centre compartment has a large principal window, now wreathed with ivy, from which the tracery is gone. Above this is a four-light flat-headed window, having a niche on each side, and above, another niche containing figures of the Virgin and Child. The side compartments are blank panelled, above, in the form of large four-light windows with geometrical tracery; and below with an arcade of pointed arches, the centre pierced with a fine double portal of several orders, and the north side by a single plainer one. So extremely beautiful an example, does the front present, of the purest age of Gothic architecture of the date of the end of the 13th century, that we cannot but feel that the church must have been a structure of no ordinary character; indeed, as its own bard expresses himself, an example of

"A rich and rare

(Mixed) Gothic such as artists all allow,

Few specimens are left us to compare

Withal."

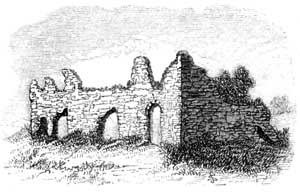

Clipston Palace.