< Previous | Contents | Next >

Tuxford

The Old Grammar School, built in 1669 (A. Nicholson, 1998).

Tuxford is a small market-town possessing a railway station on the Great Northern main line between Newark and Retford, and an excellent grammar school founded by Charles Read. Throsby, during his peregrinations through the county on horseback, speaks of the ‘clayey grounds’ in this vicinity, over which his steed could not travel more than two miles an hour. ‘About Tuxford is the most absolutely ill road in the world,’ writes William Uvedale, Treasurer at War, to Matthew Bradley, Deputy Treasurer, in a letter dated 1640, and quoted in the State Papers. But there have been great improvements since those days, and though intermingled with luxuriant pasturage and fertile plains, there is plenty of evidence of the heavy nature of the soil. Tuxford, where Jeanie Deans, the heroine of the ‘Heart of Midlothian,’ spent a night on her journey along the great north road, has long since redeemed its reputation and ‘mended its ways.’

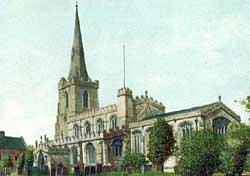

St Nicholas' Church, Tuxford c.1905.

Going back to the time to which its ancient records carry us, we find that like so many other towns and villages in this county, it can boast of association with members of eminent families, some of whom lie within the beautiful church, which is a conspicuous landmark to the traveller passing along the line. Thomas de Gunthorpe, Prior of Newstead, was buried here in 1495, and the celebrated family of Lexington, deriving their name from the village of Lexington about three miles off, long held the Manor of Tuxford. The representative of the Lexingtons, who was created a Baron, made it his chief seat in Henry III.’s reign. He was a judge, as was his brother John who succeeded him, to whose hands were entrusted the Great Seal on four occasions. Upon his death he left the Tuxford property to his younger brother Henry, who rose to the high ecclesiastical position of Bishop of Lincoln. The heirs of this prelate were Richard de Markham and William de Sutton, who divided the lands between them.

From Sutton the Lords Dudley are descended; but there is a more remarkable man still who is associated with the ownership of Tuxford. Early in the fifteenth century part of the town belonged to the Cromwells, and it came into the hands of Ralph, Lord Cromwell, who was Lord Treasurer of England, and died in 1456. It can also claim to be connected with another famous family, for on a tomb in the church was once an inscription to the memory of John White and his wife Dorothea. Sir Thomas White was the father of this John, and his mother was Agnetis Cecil, sister of Lord Burleigh, the great statesman of Queen Elizabeth’s time.

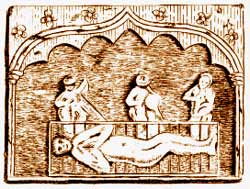

"St. Lawrence, roasting, mentioned by Gough in his Camden, still remains. He is represented on a gridiron; two men are employed in the cruel business, one blowing the fire with a pair of bellows, and the other turning the saint as a cook does a beef steak; another seems a spectator or director. The whole is a rude effort of art; I have sketched it." (Throsby, 1790).

In the church, which is dedicated to St. Nicholas, are buried some members of the Stanhope family, of Rampton, and the mortuary of the family of White, of Wallingwells, is on the north side. Captain Charles Lawrence White, of the 3rd Foot Guards, was mortally wounded at Bayonne in 1814, and a tablet is here erected to his memory. But the principal antiquarian feature is a representation of the martyrdom of St. Lawrence, who was roasted on a gridiron at Rome during the sway of the Emperor Valerian. The details of the scene are brought out in a singular manner on a sculptured stone, which has suffered like many other monuments of the past, and is now inserted in the wall at the end of the south aisle. The church is the only ancient building in Tuxford, for the place was almost destroyed by fire in 1702, and the residences are chiefly of modern construction.

In the State Papers is a letter, dated from Tuxford, December 5, 1569, from Lord Clinton to Lord Cecil, stating that the Earl of Warwick was going to Nottingham and thence to Doncaster for the purpose of suppressing the rebellion in the North. Mention is also made of Tuxford in connection with the delay of the mails to London, and the times allowed for traversing the district are well worth reproduction, as indicating the rate of travelling in those days. They are as follows: Scrooby to Tuxford, seven miles, two hours; Tuxford to Newark, ten miles, three hours; Newark to Grantham, ten miles, one and a half hours, which shows that progress was much slower on the road in the Tuxford district than on the portion between Newark and Grantham.

Tuxford does not figure in any of the records relating to the Civil War, but a stone about a mile on the road to Newark bears the significant inscription, ‘Here lies a rebel, 1746,’ and probably has reference to the movement in favour of the young Pretender.