THE head of the house of Chaworth had been knighted in 1584 and, dying five years later without male issue, was succeeded in his possessions by George Chaworth, who became first Viscount Chaworth. After serving as High Sheriff of the county in 1638, during which time he had the distasteful duty of collecting the hated ship-money, he died in 1639. It was his daughter Elizabeth who made the first personal link with the Byrons of Newstead, for she married the third Lord Byron (who died in 1695), thus creating a precedent which the poet-lord strove in vain to follow.

John, the second Viscount, was an ardent Cavalier who, when the Civil War broke out in 1642, rallied to King Charles. As events proved, Annesley lay somewhat away from the beaten track of the war in Notts., but the chief seat of the family, at Wiverton, was right in the fray. It had been fortified and defended for the king, but in November, 1645, it was compelled to surrender, and the mansion was destroyed.

Annesley Hall escaped that fate, but it felt the penalty of defeat, for Lord Chaworth’s estates were seized by Parliament and it was only by payment of a crushing “composition” that they were restored. The inhabitants of Annesley had to pay their assessment to the subsidy, and in 1647 this amounted to £1 12s. 8d. It is of interest to note that this was a few shillings more than Hucknall paid, 10s. less than Kirkby, and more than double the amount claimed from Linby.

Clerical Notabilities

In 1650 the church living was described as “an impropriate rectory worth £15 per annum, in possession of Wm. Cartwright, Esq., who received the profitts thereof to the use of Lord Chaworth”; there was then, “noe viccar nor curate, but formerly the viccar has sixe pound per ann. given him and the small tithes for his sallary.” In 1656 Christopher Sanderson was appointed “minister according to the ordinance of approbacon of publique preachers,” with a stipend of £50 a year, and the Protector’s Council “gave order that the same be paid accordingly,” - £40 for this purpose to come yearly from the rectory of Stoke (Notts.), and £10 from that of South Scarle. Sanderson quickly sought to prove his worth by sending a petition to Cromwell, praying him to put a stop to “the infection of damnable errors and heresies, and the curbing of all profaneness and libertinisme, and the training up of a young generation” of those, of his school of thinking. Unhappily he was not destined to witness the effects of his appeal, for in the following year he was succeeded in his office by Christopher Stote, a worthy who was then a staunch Puritan. Stote combined his curacy here with the rectory of Whickham, co. Durham, but at the Restoration he had to make way for the former rector. He consoled himself by conforming, and in 1663 was instituted rector of Tollerton.

Love And Romance

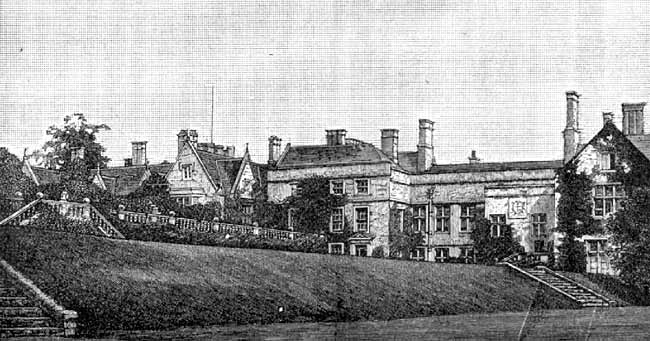

The west front of Annesley Hall and the terrace, c.1890

Wiverton House being no longer habitable, Annesley Hall became the chief seat of the Chaworths, and hither Patricius, 3rd Viscount, brought his bride, Grace, daughter of the 8th Earl of Rutland, in 1653. It is thought that he was the constructor of the famous terrace in its gardens. The earl had many daughters, and, in accordance with the old custom, the marriage may have been arranged for her, but in any event their union was a failure, and after five years of marital discomfort they were visited by the great divine, Jeremy Taylor, who had recently published; his “Holy Living” and “Holy Dying,” who came at the Countess of Rutland’s behest to compose their differences. Optimistically he reported that he found the husband “so very loving, and my Lady so perfectly satisfied with his worthy comport towards her, that she really believes herself to be a very happy person,” but he had seen only what they desired him to see. Ultimately Lady Chaworth fled to London, and as she declined to return, the deserted husband consoled himself with the company of his cousin, Juliana de la Fountaine. His attentions to this fair lady may have contributed to his wife’s departure, for scratched upon a marble mantelpiece in the Hall, and dated “Christmas, 1669” — the year in which the viscountess left him—are yet to be seen the lines—

Juliana de la Fountaine

Is worth more than a gold mountain.

The name above

Is her you love

Inspired, perhaps, by doubt of the poetic quality of this effusion, he tried another metre with the following result:

Alas, I find my poor heart will prove

Too small a vessel for o’erflowing love,

Which makes me wish thine eyes so bright had never shined,'

Or that thou hadst been from thy cradle blind,

Poor Chaworth. A strange precursor this of Byron’s love-making within the same walls—but with a difference. Byron confessed his feelings in nobler verse, and whilst Mary Chaworth rejected his suit, Juliana de la Fountain, if tradition is to be believed, refused Lord Patricius nothing that he desired.

In 1661, this nobleman had licence to empark 1,200 acres in his manor here, possibly to make up for the loss of the park at Wiverton, and several homes were demolished in order to extend the grounds and gardens close up to the Hall. Thoroton’s 'Antiquities' gives a two-page plate showing the appearance of the Hall, the church, and the gardens at that time, with a similar plate of the park and its drives when the enclosure was completed. A further enclosure occurred at Annesley in 1808, when nearly 583a, were transformed into fields.

In 1676, it was returned that there were in this, parish 104 persons of age to take the Sacrament, as by law enjoined; there were no Papists or other Dissenters. In 1682, the inhabitants were indicted at the Quarter Sessions on account of the bad condition of the king’s way called “Samon Lane,” leading to Selston. A few years later Kirkby, Sutton, and Annesley Hills, together formed one of the nine “walks” into which Sherwood Forest was at that time divided. Each walk had its own keeper who was paid 20s. a year out of the fee farm rent of Nottingham Castle.

By 1743 the population had grown, the curate (Andrew Matthews) reporting about 51 families in the parish, one only of whom was Dissenting. Mr. Matthews was also rector of Linby, where he resided, but public worship was performed in the old church every Sunday morning and afternoon. Joseph Barratt and John Weightman were then the churchwardens.

A Famous Duel

The year 1765 was marked by the London duel between William Chaworth and the “Wicked Lord Byron,” in which the former was slain. The quarrel arose out of a dispute at a meeting of the Nottinghamshire Club at the Star and Garter in Pall Mall, and concerned the quantity of game on the disputants’ adjoining estates. To settle their difference in what was then considered to be the honourable fashion, the two neighbours retired into a room where, fighting with swords in the dark, Mr. Chaworth was run through. Byron is alleged to have fled the scene in horror and to have ridden straightway to Newstead so desperately that, as the Abbey gates were reached, his horse dropped dead. Chaworth’s body was interred at Annesley, and the rapier with which he fought is preserved at the Hall. The estates passed to a cousin, another William Chaworth, who died childless in 1771 and was succeeded, by his father, Capt. Wm. Chaworth, R.N., who died at a great age in 1784. He was followed at Annesley by his younger son, George, who occupied the Hall until his death in 1791, and there in 1786 was born his daughter and sole heiress, Mary Ann Chaworth, Byron’s “Mary.”

The Hall and now most of the soil of Annesley form part of the possessions of Col. Chaworth Musters, who represents a line of distinguished travellers and soldiers.

In Later Days

When Wm. Howitt visited Annesley in 1834 (as related in his “Rustic Life”) he found the mansion a scene of chilling desolation. It had been deserted by the family, damp was disfiguring its walls, the modern furniture had been removed, and a massy beam guarded the inside of its main door as it had done since the time of the reform rioters of 1831. The property was shortly afterwards put into good order, and the domestic wing that was added after Squire Musters’ death in 1849 gave the old home its present appearance.

The new church after the 1907 fire.

In 1783, the population of the parish was 330; the census of 1801 showed that it had grown to 359, but then it steadily declined to 288 in 1861. In 1867 the colliery was opened, and by 1871 the inhabitants had increased to 1,201. The newcomers dwelt near the pits, and in 1874 the old church was abandoned in favour of the present beautiful edifice, nearer to the new population, which was practically destroyed by fire in 1907 but has subsequently been rebuilt. Of the old church of All Saints, an account, with an illustration, was given in these columns on August 12th, 1939. Its Norman font stands in the new structure, but the bells, to which Mary Chaworth and Byron had listened, and which had been removed thither, unfortunately perished in the flames.

The story of Lord Byron’s wooing of Miss Chaworth is related in the poet’s passionate verse, and has been recounted in detail by his numerous biographers, but it may be conveniently read in succinct form in Canon Barber’s excellent “Byron—And Where He Is Buried,” in which the interest is enhanced by a generous provision of portraits and illustrations of the Hall and its Byron-Chaworth relics. As Annesley had come to the Chaworths in 1439 by the marriage of an heiress, so in like manner it passed from them in 1805. when Mary, the last of her line, wedded John Musters, the sport-loving squire of Colwick. She died at Wiverton in 1832.