< Previous

NOTTS. VILLAGES

Barnby Moor has an ancient and interesting story

By JOHN GRANBY.

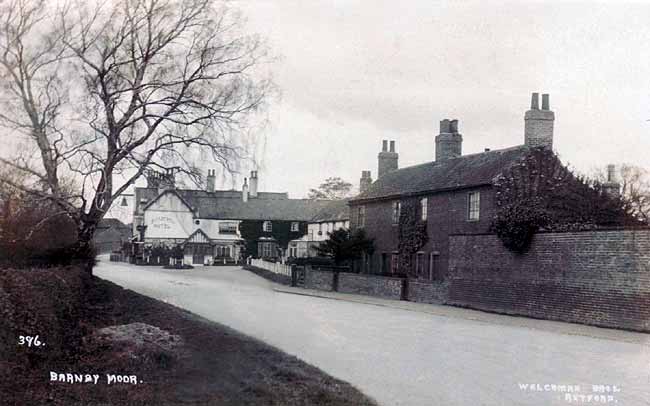

Barnby Moor in 1905.

Barnby Moor in 1905.LITTLE has been written of the annals of Barnby Moor. Indeed, one recent authority has roundly declared that “it is almost impossible to learn anything very definite or very interesting about this little hamlet." This, however, overstates the case, for if non-local sources are tapped, the village will be found to have a story not only going far back but possessing more colour and interest than that of many better known villages in the shire.

Its name, like that of Barnby-in-the- Willows, is said to derive from a Danish settler, Barni (in one of its variant spellings), and it was one of the many “bys” that cluster hereabouts and denote Scandinavian activities a thousand nears ago, “Moor” being added to distinguish it from the other Barnby, near Newark. It was a tract of exposed woodland, moor, and fen, and so it remained, largely uncleared or developed, until the close of the 13th century. At the time of the Conquest most of its land was waste, valued at but 10s., and Roger de Busli, to whom it then fell, ousted its last Saxon owners, Turverd and Sorte, who perhaps remained to cultivate as tenants the small portion of cultivated soil they had owned. Through neglect, ravages of war, or some other cause its value so diminished that within twenty years it had declined to 12d., and it was not until de Busli gave the little township to the priory he founded at Blyth in 1088 that improvement set in.

Developed By Monks.

The early monks were great agriculturists, and they lost no time in developing this acquisition, for within a short period Eustathius de Barnebi and Wiot de Bernebi released to them their properties “within the enclosure of the monks,” and it is of interest to note that these benefactions were bestowed towards the cost of building Blyth Priory and for the food and clothing of its occupants. Other Barnby gifts came to them. In 1407 John Markham and John Wryght, of Blyth, presented messuages and lands "in aid of maintenance and for the support of certain charges and works of piety.” The Rev. J. Raine’s History of Blyth” states that the priory purchased small parcels of land here from time to time; others it obtained at peppercorn rentals, and his pages recite numerous benefactions, not always by clear title, for in the 14th century Walter de Barnby and Robt. and Wm. Leman impleaded the priory before a gift was confirmed.

Mr. Raine depicts the local medieval scene. The prior was lord of the manor, throughout which he exercised considerable powers. Forest and moor still prevailed, but by hook or by crook the priory was persistently enclosing portions. Its forester, clad in Lincoln green, bearing bow and arrow, and with a staghound at his heel, perambulated the glades or watched the thickets “to protect the rights of his master, to ward off intruders, and to bring down any wil deer that may chance to come with arrow shot.” Variety would be afforded by the road that wound across the moor over which royal messengers sped, armies marched, and captives were escorted from Scotland and the North.

By the end of the 14th century Blyth Priory was holding here 14 bovates of land, each consisting of 16 acres, valued in all at £2 3s. 4d. yearly; also 8½ acres of meadow worth 1s. 6d. per acre, and rents from free tenants and cottagers yielding £1 12s. 2d. These they kept until the Reformation, when they apparently passed to the Fretwells of the neighbouring Yorkshire parish of Stainton, and at the same period the properties which had been acquired by Swineshead Abbey and Newbo Priory were granted in reversion to Sir John Markham of Cotham.

Exciting Times.

Under Edward I Thos. de Mattersey held two knights’ fees here and elsewhere in Notts, of the Honour of Lancaster, doing homage and suit at the court of the old royal manor of Bothamsall every three weeks, rendering 20s. yearly for ward of Lancaster Castle and 8s. to the Crown. In 1315 the place was officially ranked as half a vill, and the ill-fated Earl of Lancaster was its overlord. The state of the highway may be estimated from the fact that, thirty years later, the hermit of Stainton Bridge was granted protection for two years whilst gathering alms for the “repair of the causey which leads through the moor called 'Barneby More,’ to enable him to finish the work,” but the neighbourhood was so wild and the road so ill- defined that, according to Macaulay, travellers between Barnby and Tuxford in 1685 were continually losing their way.

In 1530 Archdeacon Thos. Magnus made his great bequests to Newark, which included three messuages, two cottages, 60a. of land, 40a. of pasture, 140a. of moor and a rent of one penny,

in Mattersey, Barnby, and Ranby. Next year, fearing his intentions might be frustrated by the coming of the Act against gifts for “superstitious uses,” he ordered the will to take effect at once. Barnby must have witnessed exciting scenes six years later when, during the Pilgrimage of Grace, with Scrooby, for a time, as the headquarters of the Royal army, forces were being frantically raised to crush the rebels entrenched at Doncaster but no scenes of bloodshed are recorded here.

Vanished Chapel.

There was once a chapel here of which the York Fabric rolls record that its chancel and nave were so defective that in 1480 the Archbishop granted 40 days indulgence, to those who contributed towards its repair. It was dedicated to St. Mary and was in existence in 1562, when with its chapel-yard it was held by the vicar of Blyth. No trace of it now remains.

When Blyth Priory was suppressed, the Crown retained the manor, but in the time of James I it was alienated to the Cliftons (then of Hodsock and Clifton), who eventually sold it to the Mellishes. One of the chief proprietors in 1612 was Thos. Cromwell, to whose son, Robert, was born John Cromwell at a time when Robert was converting his land into fields. As a Congregationalist this John was presented by Oliver Cromwell to the rectory of Clayworth, but in 1661 he was denounced for non-compliance with the rubrics and ejected from the living. In 1664, he was sentenced to lifelong imprisonment for alleged complicity in the Yorkshire Plot, a fate from which he was rescued by the good offices of the Duke of Newcastle. After nine unhappy years at Norwich, he returned to Barnby, where “he had a good estate" and died there almost at the moment when a volume of his sermons was published in 1685.

Famous Posting Inn.

The 'Ye Olde Bell Hotel', Barnby Moor, in the 1920s.

The 'Ye Olde Bell Hotel', Barnby Moor, in the 1920s.Under an Act of 1776 the Great North Road, which used to cross the Forest from Markham Moor to Barnby was diverted to pass through Retford, rejoining its old course a little south of Barnby. Stage coaches commenced to run along this highway during the Commonwealth and it may be assumed that the famous Bell Inn and perhaps the White Horse also, then sprang into eminence. The journey from London to York at that time and for a century afterwards occupied four days or more, and the roads were vile. Thoresby, the antiquary, reaching here in 1708, after compassing 41 miles in a day, was so well pleased that he wrote in his. diary —“Blessed be God, we found the ways much better than expectation;” but next day he was mired at Tuxford. At its zenith, in the 18th century, the Bell had stabling for 120 horses, and during the hunting season and when the Doncaster races were on, every box was full, whilst as a coaching stage it was always busy, and in the first half or that century was reputed to be the largest posting establishment in the North of England. The introduction of railways ruined the Bell for decades, and its buildings were transformed into private dwellings, a fate from which it was retrieved to flourish again by the coming of the motor car.

Romance.

Romance has not left the village untouched. The Portland MSS. contain a letter telling how the beautiful daughter of the Dappers drew admirers from near and far. “There arrived at Barnby Moor an esquire well dressed and in all things answerable to a knight errant, who inquired if there was not such a great fortune as the lady before mentioned in the neighbourhood.” When he was told that such was the fact, he declared himself the emissary of a Scottish lord who proposed by proxy for her hand, but was fobbed off by her duenna who had little liking for such Don Quixotes. A few years earlier, an imposter had affrighted the villagers by witchcraft and fortune telling warning them that they would be hanged or drowned or “fetched by the devil.” When arrested he was begged off by women, but was soon at his mad pranks again, adding house- breaking to his repertoire. “I am worn out, but press on to Barnby Moor to-night,” wrote Sterne, author of “Tristam Shandy,” but Sir Walter Scott, who was also familiar with the Bell, was more alert. He noted the changeless bustling scene, the skeleton hanging on the wayside gibbet, and observed that the only alteration he noticed was the deepening red of landlords’ noses.

A Great Fight.

Arthur Young, the agriculturist, noted in 1769 the backwardness of agriculture. Farmers still ploughed with oxen, and fertile land, unenclosed, was returning but a very small portion of its value. Hop plantations were flourishing at the close of the century, but it was not until 1807 that the enclosure took place and the parish assumed something like its present appearance. It was two years prior to that date that the celebrated fight between Jem Belcher and the “Game Chicken” (Pearce) took place on the moor, when the latter celebrated his victory at the Bell. The inn figured prominently again about 1830, when the followers of “Captain Swing” came to these parts and set haystacks alight at Barnby. Its landlord mounted some fifty men, who scoured the neighbourhood, and were rewarded by finding two incendiaries, who were convicted and sentenced to transportation.

The parish has not been without its charities, and in 1790 the overseer was distributing 36s. 6d. a year from this source among the poor, but in 1839 it was found that the distribution had lapsed. Some of the funds could not be traced, but the Barker bequest of £20 was recovered. In 1875 part of the parish was absorbed by the newly- formed ecclesiastical parish of Osberton, and in 1937 the Notts. County Council decided to make the Great North Road throughout the county of the uniform width of 120 feet, at the cost of the Ministry of Transport, the stretch between Barnby and Markham being the first portion to be treated. To-day Barnby is known as a pleasant village, forming a joint-township with Bilby, in the parish of Blyth.

< Previous