Haughton's glory and its decline

The first Sir William Holles died in 1541 leaving two sons, Thomas and William. Of Thomas the elder, little need here be said save that he did not inherit Haughton and after squandering his fortune he died in a debtor's goal. To the more prudent William fell this among other manors and it was under his regime at "princely Haughton" attained its outstanding glory.

KNOWN as "the good Sir" William," the new owner found Haughton much to his taste, and from all his possessions he chose this as his seat, "both pleasant and agreeable, lying between the forest and the clay and partaking of the sweet and wholesome air of the one and the fertility of the other, having the River Idle running through it," as the family historian wrote. Preserving the tower and the south side of the Stanhope building, he enlarged and beautified it in 1545, and his splendour and hospitality became proverbial, his goodness and benevolence gaining him the title of "the good lord of Haughton."

A MINSTREL TROUPE.

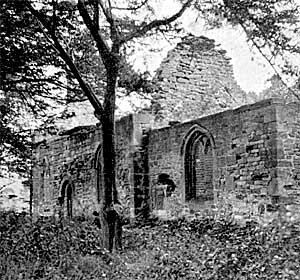

St James' chapel, Haughton in 1915.

At the Hall he maintained a jester, minstrels and a troupe of actors for his own entertainment and that of his guests, the players also giving summer performances in various parts of the county and appearing before the mayor and corporation of Nottingham, and invariably closing with a prayer for; Queen Elizabeth and their right worshipful master. His grandson's account of the regular Christmas scene states that "he always began his Christmastide at All Hallowtide and continued it till Candlemas, during which time any man was permitted to stay three days without being asked whence he came or what he was. He allowed during the 12 days of Christmas a fat ox every day with sheep and other provisions answerable," and the yearly round was spent in almost regal state. He died here full of years and honour in 1591, and was buried "in his parish church or chapel of Houghton," which he had restored, and in which it had been his custom to worship twice every day.

THE EARL OF CLARE.

With Sir William's death liberality ceased, for his successor, John of Holles, was quite another stamp, but much of the splendour remained. The new owner "was a man of action who had fought in Holland and served against the Spanish Armada and his long life was packed with incident in which his home took its part. He had been affianced by Sir William to a kinswoman of the Earl of Shrewsbury but upon achieving independence he immediately married Ann Stanhope of Shelford and thereby caused a feud. In 1598, when accompanying Lady Stanhope home from the christening of his son, Denzil, at Haughton, he met Gervase Markham, the gallant and champion of Lady Shrewsbury, and presently they engaged in a duel in which Markham was run through. The Earl of Shrewsbury surrounded Haughton Hall with men to prevent the victor's escape in the event of the wound proving fatal and the Earl of Sheffield, Holles' cousin, sent 60 men for his protection, but Markham recovered.

BOUGHT HONOUR.

In 1615 James I. commenced to replenish his purse by the sale of honours and next year Sir John paid £10,000 to become Baron Haughton and subsequently paid £5,000 more to be Earl of Clare. At Haughton he was visited by many distinguished guests, among them Prince Henry whose premature decease paved the way to the throne for his brother Charles. There, too, came the famous Earl of Strafford to woo the earl's daughter Arabella, "a vivacious brunette with a brilliant brain and charming character" whose early death caused a long estrangement with her relatives, her children being brought up at Haughton. Clare died in 1637 at his Nottingham mansion, Clare (or Thurland) Hall, and it is related that on the last Sunday of his life he went to St. Mary's Church before prayers and suddenly putting his staff on a particular spot exclaimed "Here I will be buried." A marble monument covered his grave until 1804 when it was superseded by a less elaborate tomb which; in turn has disappeared and only a mural tablet in the south transept now remains.

THE CIVIL WAR.

The second Earl of Clare, after striving to avert the Civil War fought for King Charles, but later, disapproving of the royal policy, he withdrew to the seclusion of Haughton, made his peace with Parliament and under the Commonwealth played bowls with the regicide, Whalley, and entertained distinguished neighbours. At that time the chapel was "wholly ruinous and unfrequented" except by bats and the blame for this was ascribed to the Countess, "the puritanical lady in her new-fangled religion."

Denzil Holles, Baron of Ifield.

The earl's brother, Denzil, had already taken a leading part against King Charles, with whom he had been on familiar terms in his early Haughton days. He was one of those who in 1629 had held the Speaker in his chair until resolutions obnoxious to the King had been approved, and he was also one of the five members of Parliament whom Charles vainly attempted in person to arrest in the House before hostilities broke out. He raised a regiment which he led in the early battles, but upon objecting to his party's excesses was impeached and fled into exile where he worked for the Restoration. Under Charles II he served in high offices, was created Baron Ifield and died in 1680.

These two brothers, both Haughton born, were essentially men of peace who were soldiers awhile in their own despite, but their kinsman, Gervase Holles the antiquary, was a fervent royalist who provided a regiment with which he stoutly fought and when the cause was lost shared in the exile of the future Charles II. He was 'buried at Mansfield in 1675. His brother brought .his own only son to the "royal standard at Nottingham, saying "that had he twenty sonnes they should all serve the king or lack his blessing," and in 1644 the gallant youth was slain in the fight at. Muskham Bridge.

DECLINE AND FALL OF HAUGHTON.

When the son and heir of Gervase Holles died his possessions all passed to the 4th Earl of Clare, a courtier politician who added to his enormous wealth by espousing Margaret Cavendish, a daughter and chief heiress of the 2nd Duke of Newcastle. For Haughton this marriage was momentous, one of its first effects being a scheme, to glorify the Hall, into a residence fit tor his bride, William III granting him 3,000 trees from Birkland and Bilhagh, worth £1,500, for the purpose. The plan was frustrated by the death of the duke within a year of the wedding, and Welbeck forming part of Margaret's inheritance they made the Abbey their chief seat.

Haughton was not immediately deserted for it was from its Hall that its owner, now Duke of Newcastle, upon being advised that the king intended to pay him a visit, wrote inquiring whether Nottingham Castle or Welbeck was to be so honoured. In 1707 he was dating letters from it and as late as 1740 it must have been habitable as the Rutland MSS. of that date have a list of paintings there by Titian and others.

The decay of Haughton Hall may have set in with the death of the duke in 1711 when, by a long disputed will, it with many other properties descended to Thomas Pelham who added Holles to his name and achieved fame as a statesman. In that year the bereaved duchess presented Queen Anne with 100 deer from the park and when the new owner at last obtained possession of it he appears to have taken little interest in such a small portion of his vast possessions.

HAUGHTON'S LATER DAYS.

Haughton school dates from 1692.

In 1688 the Earl of Clare gave a site outside the park gate for a school which was built and endowed by his steward, Henry Walter, for the children of Haughton and neighbouring parishes. The building, enlarged, yet serves that purpose and the master's house remains practically unaltered. By the middle of the 18th century the Mellishes had property here which they sold in order to purchase their seat at Blyth, and a writer of that time described the utter loneliness of this place. Towards the end of the century plantations were made, the ancient water-mill was at work and hops were cultivated. Throsby recorded that the Hall was in total decay and "Haughton has now only a house or two."

Today Haughton is but a ghost of its former self. A farmhouse occupies the site of its historic Hall, preserving a few of its stones. The moat remains as also do the ancient duck decoy and fishponds but the noble park has long been transformed into fields and the only visible relic of Haughton's erstwhile splendour consists of the ruins of the chapel, now carefully preserved within a railed enclosure in the midst of a small plantation, in a most lonely situation strangely at variance with its brilliant past.