Nuthall

18th and 19th century cottages on Nottingham Road, Nuthall (photo: A Nicholson, 2004).

Nuthall From Earliest Times To 16th Century

THERE is evidence, that from ancient times Nuthall has been famous for its trees. The name itself proclaims that a thousand years ago it was a "healh," a nook or corner, where nuts grew, and the derivation makes it plain that "Nuthall" and not "Nuttall" is the correct form of its spelling.

Trees and undergrowth marked it for centuries. For the reparation of the Trent Bridge at Nottingham in 1457-8 it supplied trees, the bridge-wardens paying for the lopping of their branches; in 1486 21 loads of specially selected piles of stout timber came hence for further repairs, and under Elizabeth the corporation purchased "200 gross of kids or bundles of gorse" for "the cole-pyttes at Radfourth," where they were burnt at the bottom of the shaft to draw out the foul air from the workings and allow it to escape upwards.

It may, therefore, be regarded as forest land and heath, which the Saxons cleared and tilled with such success that its soil became knows for its fertility. Domesday records that "Nutehale" had two manors and a church in 1085, and that the Conqueror retained part for himself, and included the rest in William Peverel's great fee. Its Saxon owners were dispossessed, but one, Aluric, who had held extensively under the Confessor, and was permitted to keep some of his possessions, here cultivated as the king's tenant lands which had formerly been his own.

Ownership Changes.

The presence of an early Norman font seems almost to hint that the Saxon church of timber gave way to one of stone soon after the Conquest, but nothing is known of any such structure, and the oldest existing masonry is the base of the tower dating from about 1200. A century earlier the Peverel manor was being held by the St. Patrick family, and when their overlord founded Lenton Priory, about 1103, Galfrid de St. Patrick gave Nuthall Church to swell its endowment.

The benefaction caused; a dispute, for in 1200 the donor's grandson claimed that the grant had been obtained by undue influence when his grandsire was on his deathbed. The claimant paid to have a jury to investigate the case, and as the patronage was afterwards held by the St. Patricks he apparently won the verdict.

The Peverel fee was forfeited in 1154, and 20 years later Henry II bestowed it upon his youngest son, the faithless John, who was here when, as Earl of Mortain, he gave Lenton Priory heather from his woods. For some unknown reason Prince John seized the old Peverel manor, probably because Robt. de St. Patrick refused to join the plot against the absent Richard I, but when Coeur de Lion returned and captured Nottingham Castle the manor was restored, though Robert had to pay three marks to secure possession.

The Cokefields.

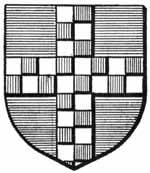

Arms of Cokefield.

By the commencement of the 13th century the Cokefields had some interest here, and by acquiring the St. Patrick manor they became lords of the vill and so remained until about the middle of the 15th century. Some time near 1200 a church of stone was built and the monks of Lenton obtained from Adam de Cokefield the gift of a rental of 8s. out of the mill on the rivulet towards Hempshill. His widow gave them the mill outright, granting that the inhabitants, saving only her household, should grind their corn at the mill and any seeking to have it ground elsewhere should forfeit it to the priory, defaulters being remitted to the. manor court for correction.

Lawsuits began early at Nuthall, and in 1281 another important claim followed that of Wm. de St. Patrick against Lenton Priory. Robert de Cokefield had given the manors of Nuthall and Basford to his younger son John, but now they were claimed against him by another Robert who was already in occupation. John produced a document showing that the claimant was tenant for life only, and thus entered upon his inheritance. The claim seems to have lingered for in 1318 when this John settled the manor upon his son and heir of his. body a Reginald entered his claim on the back of the deed. Nuthall and Watnall then accounted for a whole vill and John de Cokefield and Robt. de Kimberley were the lords thereof.

Strelley Shillings.

Monument of Sir Robert de Cokefield.

Near the close of the 14th century the 200-year-old church was replaced by another erected in whole or part by Sir Robert de Cokefield, whose dust lies beneath an alabaster effigy in a founder's recess in the north aisle where once a chapel stood. He was lord of the manor and a knight of the shire in several parliaments, who received payment for 43 days' attendance at Westminster in 1388 and held various official positions in the county.

The chancel was begun when the rest of the edifice was completed, but the fine south porch was apparently not completed by 1399 when Richard II was deposed, for the heads of Henry IV and his queen adorn its walls. In 1391 complaint was made that "the king's road towards Nuthall, called Notale-lane, is ruinous and ought to be repaired by that township." Perhaps the damage was caused by the cartage of material for the new church.

The Strelleys long had interests in Nuthall, and in 1430 Sir Nicholas Strelley included it among the villages whose "very poor" were to share in his carefully-guarded benefaction. The will stipulated that "no one who uses any kind of unlawful games, or haunts taverns at unlawful times of night, shall have the aforesaid sum"— part of 100 shillings—"unless he is willing to give sufficient security" for abandoning such evil courses, and that any blacksliders shall refund such money as they have received.

The long ownership of the Cockfields ended in 1543 when John de Cokefield died childless. His wife, a Foljambe, assumed the garb of perpetual widowhood and was invested by John, Bishop of the Isles, with the pallium of a vowess and the precious ring that symbolised espousal to Christ. She, like her husband, lies buried in the church, and their great-niece. Margaret Taylboys, conveyed Nuthall in marriage to John Ayscough, who founded a new race of local lords.

Anne Askew.

In 1539 the parish could furnish only seven men fit to bear arms, a total that compared ill with the 38 of Annesley able to serve as archers or billmen. They were a sort of home guard and a Nottingham record of that time is also suggestive of present-day conditions. In 1544 the servant of Sir Henry Pole "of Notale " was charged with buying more corn than he was entitled to and hoarding it in the town until wanted. The Poles were persons of note, who in the following century intermarried with the Slaters, the Chaworths of Annesley, and the Sedleys who inherited the Nuthall estate.

The family seat of the Ayscoughs was in Lincolnshire, but upon acquiring Nuthall they occupied the manor house, and there Anne Ayscough (or Askew), according to tradition, was born. Unfortunately, the parish registers do not go back far enough to test the claim, which is extremely doubtful inasmuch as Anne was born in 1521 and the Cokefields owned the manor for more than twenty years to come. Another tradition tells that she spent part of her maidenhood here when her brother Edward was in residence, and although this is unproved it may be that, after her husband had "put her out of his house" at Kelsey as a heretic, she found refuge here for a time after 1543. All that is clear is that this early martyr was of the family that held the manor at that period.

Her Protestantism was intense and fearless and not without effect upon the Reformation. Twice she was imprisoned and released by powerful influence, but refusing to-be silenced she was thrown into the Tower and in 1546 was cruelly racked and burnt at Smithfield. It is said that though she sought the martyr's crown the chief object of her persecutors was to strike through her to her friend Queen Catherine Parr, who was protecting Cramner and influencing the king.

Henry's anger was fomented and in a fit of passion, he signed a bill of attainder. "Good hearing it is," he exclaimed in his fury, "when women become such clerks, and a thing much to my comfort in mine old age to be taught by my wife." He had been indifferent to the fate of Anne Askew, but was too attached to his sixth queen to sacrifice her and when Lord Wriothesley and his myrmidons came to convey her to the tower they were ordered away with unbridled roughness. Catherine survived him only by one year, but that was long enough to witness the coming of the Protestanism for which she had imperilled her head and for which her Nuthall friend had died.