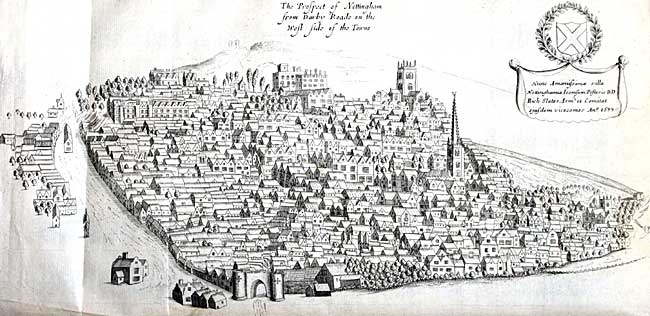

Nottingham viewd from the north-west in the 1670s.

Gainsborough. All the horse that had been raised in Nottinghamshire on behalf of the Parliamentary forces, together with the foot companies, marched to Gainshorough (1643), where Colonel Cromwell had his first battle, and was victorious, killing the King’s General, Sir Charles Cavendish ; the Earl of Newcastle arriving too late, but just in time to see the rout.

Mrs. Hutchinson takes two volumes to tell the local history of the war, chiefly so far as her husband was concerned. Mr. Bailey gives considerable space in his Annals of Nottinghamshire to the record. We can barely skim the report. Mrs. Hutchinson—who, by the bye, was a thorough woman in her way of looking at things, and a strong partisan—tells how her husband saved Nottingham from being at the commencement of the war deprived by Lord Newark of its gunpowder, but Mr. Bailey doubts the accuracy of the story. Mrs. Hutchinson tells of the appointment of local War Committees, and their operations; of Captain Ireton’s troop of Horse; of Newark’s thorough adherence to the King, backed by nearly all the County landowners, and Nottingham’s decision for Parliament — Colonel Hutchinson becoming Governor of Nottingham Castle; of the sorties from one town to the other, and so on. Mr. Bailey gives particulars of an assessment made by the Corporation of Nottingham towards war expenses, 438 persons being assessed, and £540 realised, which was followed a month later by another assessment for repairs of bulwarks, lights, and coals for the night guard.

Works. The works constructed about the Town were of a very extensive character, so that it would require 3,000 men to defend them, and these could not be had for the purpose, so all the ordnance (fourteen pieces) were removed into the Castle, which was strong naturally," but the buildings were very ruinous and uninhabitable, neither affording room to lodge soldiers, nor provisions. Many people took up their residence in the Castle, and their families were lodged in the villages, much poverty and wretchedness being endured. Colonel Hutchinson made a fine appeal to his men that they must be prepared to go upon hard duty, fierce assaults, poor and spare diet, perhaps famine, and want of all comfortable accommodation, with the hazard of losing their lives, all of which for his own part he was resolved on.

One night six hundred Cavaliers reached the Town in the dead of night, seized the sentries, took possession of the Town, and it was not until the next morning that the Governor realised the position, when, calling out the garrison, he found that not more than one third of the men had remained through the night in their quarters ; two hundred were absent, of whom eighty were taken prisoners, and there were fewer than one hundred men in the fort. The Newark men had taken possession of St. Nicholas’ Church, from the top of the tower of which they poured musket balls on the Castle men. The houses of all the Roundheads were ransacked and plundered ; the prisoners were confined in pens in the Market Place, and were afterwards removed to Trent Bridge Fort.

For five days the Cavaliers held the Town, but assistance arrived from other towns, and the Newark men departed; the new visitors from Derbyshire resorting to plunder, and an attack upon the Trent Bridge Fort bad to be abandoned.

Newark. Newark early declared for the King, who put four hundred men into the Castle, and thus commanded the passage over the river, strengthening the Town with earthworks, and then with a further force making excursions into Lincolnshire, to Melton, to Oxford, Northampton, Ely, Nottingham, and elsewhere. The four hundred men for the Castle were increased to four thousand for active work.

Trent Bridge. In a fight at Trent Bridge when attacked by forces from Newark, fifty prisoners were taken, ten killed; three hundred horses, two hundred arms, and five pieces of ordnance were taken; Bridgford was plundered, and the men inhabitants taken prisoners. Incendiary fires occurred in Nottingham, "insomuch that the weomen were forced to walke by fiftie in a night to prevent the burning." On a certain Saturday, at eleven o’clock in the forenoon, men were seized at Trent Bridge "disguised like markett woemen, with pistolls, long knives, hatchetts, daggers, and greate pieces of iron about them," with provision to assassinate the guards of th bridge. Trent Bridge Fort being lost, one had to be made on the Leen Bridge, and two arches had to be pulled up, hot both were afterwards gained and repaired.

Trent Bridge Fort. Colonel Hutchinson determined to storm the Fort at Trent Bridge in possession of the Royalists, at a time when they had been drawn off for an expedition into Lincolnshire, and for that purpose took a survey of the situation from the top of St. Mary’s Church. The Fort was attacked, and after five days the Royalists evacuated, leaving considerable quantities of sheep, coals, oats, hay, lead, etc., which had been taken from the townsmen.

St. Peter’s Church. The Newark men got into the Town again on 15th January, 1644, and took possession of St. Peter’s Church, there being one thousand Cavaliers in the Town, and beyond the Trent were the forces from Belvoir and Wiverton. They had come to demand possession of the Castle, but were repulsed, the foot soldiers being almost up to the middle in snow.

Muskham Bridge. Extensive arrangements were made by the Parliamentarians to attack Newark by forces from Nottingham, Lincoln, Derby, and elsewhere, who were, however, completely routed at Muskham Bridge, and the Parliamentary army lost four thousand stand of arms, eleven pieces of brass cannon, two mortar pieces, and about fifty barrels of gunpowder. Prince Rupert appears to have aced with great recourse and moderation.

Persecution. It is not to the credit of Colonel Hutchinson that be at the "instigation of the ministers and godly people" imprisoned some of his chief cannoneers "for separating from public worship, and keeping little conventicles in their own chambers," although they "were otherwise honest, peaceable, and very zealous, and faithful to the cause, but the ministers were so unable to suffer their separation and spreading of their opinions, that the Governor was forced to commit them, yet when this great danger was over he thought it not prudent to keep them discontented, and then employ them, and therefore set them at liberty, for which there was a great outcry against him as a favourer of Separatists." Poor human nature Alike faulty in governor, ministers, and godly people!

There were attacks made from Nottingham upon Royalist troops at Syerston, Elston, Thurgarton, Southwell, and elsewhere. Newark was for the third time besieged, and famine and disease, and the plague, did their awful work, but a relief party came by way of Leicester and Melton, and though severely attacked, managed to convey food to the Newark garrison, and a relay of five hundred dragoons. In 1645, the plague was very prevalent in various parts of the County, trade was suspended, agriculture neglected, famine, wasting, bloodshed, rapine, and all other ills prevailed.

Trent Bridge Again. On a Sunday in May, 1645, a party from Newark stormed the Fort at Trent Bridge ; the Town was in consternation; no Sunday was kept, and bad the force proceeded to attack the Town, it must have surrendered, for Colonel Hutchinson was in London defending his character, which seems to have been unjustly assailed.

"After the defeat at Naseby, the broken forces of the Royalists mostly repaired to Newark, now the best and strongest garrison which remained to the King." It was now determined by Colonel Hutchinson to clear Shelford and Wyverton.

Shelford. The men in charge of Shelford got on the Church tower and fired on the attacking force, but straw was obtained, and fired, and the company smoked out. Afterwards the governor and about two hundred of the garrison were slain, no quarter being given them, about one hundred and forty others being made prisoners. Colonel Hutchinson does not shine in this want of clemency, judging by modern ideas.

Wyverton. Mrs. Chaworth Musters has written a book— A Cavalier Stronghold: a Romance of the Vale of Belvoir – in which she has collected a number of local traditions and weaved them into a narrative. The stronghold is the ancient manor house at Wyverton, formerly called the Castle, a building with round turrets at the angles, and which was guarded by a moat, a couple of earthworks, or other defences, with "covert way," or sunk road. This house was held by the Royalists, and after the siege of Shelford would have been stormed, but submitted upon terms.

Surrender. The King, after the loss of his cause at Naseby, came to Newark, went to the "White Hart" at Tuxford (on Oct. 12th, 1645), then to Welbeck, where he heard of the Scotch army advancing to Newark, upon which he returned and abode at the Old Palace, at Southwell, from which he had to flee on a force advancing from Nottingham. There was now the Scottish army at Newark, the headquarters of the General being at Kelham Hall. The King, meanwhile, went by way of the Trent, via Belvoir, to his last effort at Oxford, whence returning, and slipping away in disguise, be on the 4th day of May arrived at time "Saracen’s Head," at Southwell (then called the "King’s Head"—a name which was for obvious reasons changed). Here, in the dining room, the King sent for and met the Scottish Army Commissioners, and dining with them, and then went under an escort to Kelham Hall, where be signed an order for the surrender of Newark, and after two days he was marched along with the Scottish army towards Newcastle. "From this time his Majestic found himselfe entered upon a state off thorough captivitie in which he experienced afterwards no other varietie but that off frequently changing his jail and jailers, till the time of his unhappy execution.’’ When he had spent eight months in vain hopes and fruitless propositions at Newcastle, he was delivered up to the Parliament for four hundred thousand pounds. "The Parliament in their turn were obliged to resign him to the armie, and the armie, after 2 years of imprisonment, brought him ignominiously to the scaffold."

Mrs. Hutchinson suggests that the King did the worst thing he possibly could have done, not only in giving himself up into the hands of a hired army, who sold him, but that had he given himself into the hands of the English Parliament it would have been their ruin, for the Presbyterian and Independent factions would at once have divided, whereas by his action an open rupture was prevented.

Cromwell. Cromwell went to Southwell in 1648. "He intended to have taken up his residence in the Palace, but finding that it had been rendered unfit by the Scotch soldiers, he contented himself with that apartment at the Inn which had before been occupied by the King." He then marched northward through Mansfield.

The ruins of the Bishop's Palace at Southwell, as seen in the early 19th century.

Destruction. After the surrender of the King, Parliament ordered all the places of strength in the Midland Counties to be dismantled. So Newark Castle was destroyed. The old Palace at Southwell suffered in like manner. The Minster was saved through the interposition of Edward Cludd, who had settled in the neighbourhood. Nottingham Castle was favoured, owing to the Town having aided the Parliamentary party, and so was kept for a garrison; but in 1650 Colonel Hutchinson procured an Order for the demolition of the works, and the Corporation were pleased to be relieved of charges for the garrison. Cromwell, however, coming through Nottingham, and seeing what had been done, was highly displeased.

Death. As a prisoner in the Isle of Wight, the King, while negotiating with the Parliament, was carrying on intrigues with his partisans in England and Scotland, which brought on what was called the second Civil war, and the invasion of England by Hamilton, whose army Cromwell destroyed near Preston. The soldiery now clamoured for what they called justice on the King. and Cromwell and the heads of the army, probably despairing of any reliable arrangement with the Monarch, in whose veracity they had lost all confidence, decided to comply with their demand, brought the King before a tribunal, whose proceedings must be called a sham trial, followed by the signing of the death warrant.

Charles is called the Martyr, and such he was, but he was not a martyr for his religion, but to his profound conviction of the Divine Rights of Kings. Kings have divine rights, and they have divine obligations. God has joined the two together, and woe be to the man who puts them asunder. The people, in like manner, have both the rights and obligations of obedience to law and order, and the security of good administration, and the protection of life, liberty, property, and the general public welfare. When the rulers and the ruled co-operate, the result is a happy king and a happy people ; but when either of them ignore their duties, and a conflict ensues, the weakest must, whether justly or unjustly, go to the wall.