Bulwell

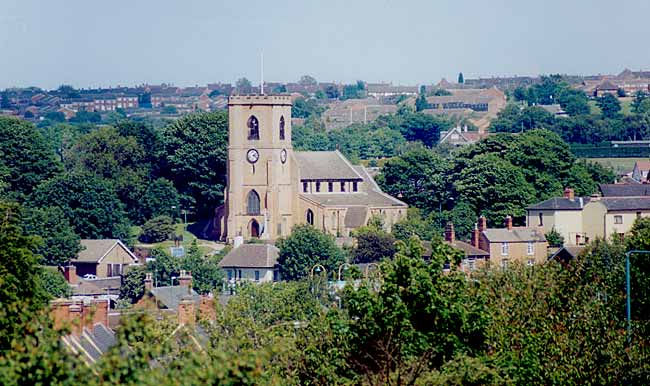

View of Bulwell church (photo: A Nicholson, 2003).

Name. The name is usually supposed to have been derived from the spring which runs out of the Bunter Sandstone over a bed of clay, near to the northern end of the Forest, called "Bull Well." Dr. Mutschmann, in "The Place Names of Notts.," suggests that the first part of the name may stand for a person — Bulla, or a bull, or it may describe the bubbling sound produced by the flowing water of the spring.

The architect of the National Schools, having a sense of humour, embodied on a stone on the building the pretty legend of once upon a time a bull digging his horns into the rock, and the water gushing out.

Boundaries. The area of the parish is 1,647 acres. A Scout boy getting up early in a morning, having obtained leave from the farmers, will easily find the boundaries by the following line: The east side and south end of the Forest are the boundary lines; the Basford Workhouse is outside, but its Hospital is in. Bagnall Dye Works are out, as is Cinder Hill Pit, but the Colliery Offices are in. Hempshill Hall is out, but its farm buildings are in. Blenheim Farm is in. but Bulwell Hall Farm is out. Proceeding by the plantation on the northern side of the Park, and through the Fishponds towards the Forge Mill, which is out, as is the Railway gatehouse, but a tongue of land between the two Railways is in, and so we return to the Bestwood Deer-leap. The altitude is 260 feet above sea level near to Bulwell Wood, and 143 in the lower part of the Leen Valley.

Geology. The Magnesian Limestone here is about 30 feet in thickness, and has few fossils of a marine type. Hollow casts of shells occur in a particular band. The Permian clay deposited over the stone is about 30 feet in thickness, and it is suggested that the clay has been the sediment from the still waters of a shallow enclosed sea or lake. It is used for flower pots and bricks. It thins out in the direction of Quarry Road, the Magnesian Limestones coming to the surface. There are valuable beds of Lower Mottled Sandstone, indicating that powerful floods swept over the district, flowing mainly from the north-west.

At Cinder Hill (the pit of which is in Nuthall) Coal is reached at a depth of about 150 feet, the seam now worked being the Top Hard, and about 4 feet 0 in. thick. It is 660 feet from the surface.

At the Bulwell Pit the Main Bright seam is reached at a depth of 546 feet from the surface, and is three feet thick.

In a boring for water on Bulwell Forest, as given by Mr. Shipman, the Lower Mottled Sandstone, and Bunter Pebble Beds reach there to a depth of 160 feet, where the Permian sets in with seven feet of clay, 38 feet of Limestone, and 12 feet of light bind. Below are the Coal Measures.

At Bestwood, just east of the parish, Clowne coal, 4 feet 3 inches thick is reached at 623 feet, and Top Hard, 6 feet 8 inches thick at 1244 feet, there being also half a dozen unworkable seams.

There is gravelly drift of glacial origin, with boulders in several parts, particularly in the hill on which the Church stands, and north and south thereof, on the crest of slopes rising 40 or 50 feet above the water of the Leen, the valley of which has been washed out.

A "fault" has been proved to have a throw of 261 feet in the workings of the Cinder Hill Colliery, yet in the quarried Permian Limestone and Triassic sandstones, at the surface, it has only a few feet.

Let us stand still for one minute and consider what is implied and involved in the foregoing statements. Vast ages must have succeeded each other in the process of the formation of coal and rocks of various kinds. A warm moist atmosphere in which mighty ferns and other vegetation grew, must, after enormous periods of time, have been followed by intense cold, and an immense burden of ice long continued. The surface of the earth where Bulwell now stands must have alternately sunk and been raised. A mighty force washed distant rocks on the west, and covered the land and vegetation, whereby gases were generated and coal formed. The hills to the north of Bulwell may have been washed down, and carried into the Trent Valley, and gone to form Lincolnshire. And so age after age with mighty forces of water and frost, of heat and wind, of sunshine and storm, passed over the land, followed by a period for great and wild beasts, until the time came for man to appear, and to what we now call Bulwell he came.

Saxons. There are no traces of occupation before Anglo- Danish times, and little even then. Doubtless the land, having gradually been cleared of trees, was cultivated, especially in Norman times, in accordance with their usual practice, by a rotation of crops, in a three field system, and this system long continued in Bulwell, and to some extent even to the last century. A plan of the Bulwell Hall estate, when it was sold in 1864, shows the Clay field in long, narrow strips, reaching from Coventry Eoad to a brook at the top. The Sand fields, Dob Park fields, and Broomhill fields occupied the space between Highbury Vale road and the Forest, and were even at the date named cultivated as open fields, in strips belonging to many owners. The land west of the Main street looks as if it had been anciently so divided.

There is one custom which the Anglo-Danes left, and which prevails in Bulwell to this day, that where copyhold lands have been held by a man who dies without a will, such lands and tenements descend to the youngest, instead of to the eldest son, or if the owner had no children, to the youngest brother. The reason for this seems to have been that the youngest son would have the greatest need, for the eldest would have been married and settled on other lands, or have gone to the wars. There is no evidence of an immoral claim by the lord of the manor having ever prevailed in our district, although it did in Scotland.

Normans. When William conquered the Anglo-Danish forces in 1066, he assumed that he had, by virtue of his conquest, obtained a right to all the land in England, and poor Godric, the Saxon, who had land for a manor in Bulwelle, had to surrender, and it was given to the Norman, William Peverel, who was made lord of Nottingham Castle, and many manors were given to him. There was two carucates (?240 acres) of land apparently cultivated, and one half seems to have been kept in hand, and the other let to a villein, who had one bordar. The word villein did not, as now, mean a vile and wicked person, but a tenant who had to render service to his lord, and was not free, and the bordar was worse off still, for he was sold with the land. There was only two acres of meadow, and by the Conquest the estate had decreased in value from twelve shillings per annum to five shillings, being equal to £710s. now.

There was also land in Hamessel, now called Hempshill, which Dr. Mutschmann suggests has the appearance of a man's name joined to an abode, or a hill. This now forms part of the parish of Bulwell, on its western side. Here 61/2 bovates (? 971/2 acres) of land was assessed to the Danegeld. There were two sochmen, that is, ordinary tenants, who usually accompanied their lord when he went to the wars, two villeins, and two bordars, and four acres of underwood. This land was subject to Hochenale (Hucknall) manor, but in some way belonged to Bulwelle, and Watenot (Watnall).

The Manor. It will not be interesting to follow the ownership of the Manor, but some items must be given.

William Peverel, the first lord of the manor, seems to have lived a useful life, and towards its close, about forty-years after the Conquest, he founded, and largely endowed, Lenton Priory, but Bulwell was not part of the endowment (see "Lenton," p. 16). William Peverel the younger (there were three or four William Peverel's) went wrong, and was charged with being concerned, with others, in taking the life of the Earl of Chester, and all his estates were forfeited to the crown.

In the time of Henry II. (1154-89) Stephen Cut had become lord of the manor of Bolewell. He married his daughter to Reymund de Burgarvell, and handed the estate over to him, but subject to Reymund finding for Stephen all the necessaries of life. Reymund, however, died, and the King thereupon seized and held the estate.

Philip Marc. Philip Marc was presented by King John with the Township and Advowson of Bulwell. He was Sheriff of Notts, from the 12th of John to the 9th of Henry III. (Yeatman p. 395) and Keeper of the Hays or Parks of Notts., one of which was Bestwood, and another Bulwell Wood. He had a bad reputation for extortion, and as being a man who would carry out the wicked directions of King John. Thus in 1207 he was ordered to get 100 pounds from "the three men of Newark," and others, in other words, compel them to pay the King. The men of Lexington had also to give "the Lord the King 100 pounds to have the King's peace, and to spare their town from being burnt to the ground" (History of Newark, p. 53). In those days ministers of the Crown, and other officials, were not, as now, paid salaries, but were rewarded by gifts of places of profit, and Philip Marc was granted the Manor of Bulwell (which had been forfeited) and the right to present the priest. So entirely hated was Philip Marc that in the famous Magna Charta the nobles put in a clause which they required the King to sign:—"Item 50. We will remove absolutely from their bailiwicks (in addition to eight persons specified) Philip Marc and his brothers, and Geoffrey, his nephew, and their whole retinue." This looks very much like saying "They are a bad lot" John signed it, but of course he did not remove Philip, and the year following death removed the King Time passed on, and Philip provided for his body to be honourably entombed at Lenton Priory, and gave some land at Keyworth for his soul to be prayed for, but how he was dealt with at the tribunal where the rule is "Be not deceived; God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth that shall he also reap," is not recorded.

The King gave the Church to Henry Medicus (Leech), and Philip Marc had the farm of Bulwell to sustain him for life. In 1234 the Sheriff accounted for Ann, widow of Philip Marc, to have C. s. (?100 shillings per year) as long as she lived, from Bulwell, for several assarts, that is enclosures of land made from the forest.

The township, when it was presented to Philip Marc, was valued at 100 shillings, equal to £125 now, so its value had much increased, but a little later the King received for the whole town of Bulwell, with ten bovates (? 150 acres) in Hendeshill (Hempshill) £7 a year, and there was in Bulwell 11/2 carucates (? 180 acres) which in the time of William Peverel was held subject to providing for service when required, a horse with a halter. The land was given by King John to a man who rejoiced in the name of Roger Rascall. Let us hope that the man was better than his name.

About 1223 the men of Bulwell as a community had the manor to farm during the King's pleasure, and they had also the advowson of the Church. They had further in 1228 obtained the Common of pasture in the Wood of "Beskwood, to the great Street."

That is, they were able, either by grant from the King, or in some other way, to pasture their cattle in Bestwood. Mr. Wm. Stevenson is of opinion that "the great street" refers to the road on the north-west of Bestwood, because in 1251 Beskewood is described as a hay or park of our Lord the Kinge "wherein no man commons,'' (Dukery Records, p. 406,) that is no man hath any right to send cattle for pasture, but to my mind the words "the great street," convey the idea that Rufford Road is meant. We must remember that Bestwood was at that time a great enclosed park of mighty oaks.