Archbishop Sandys.

Archbishop Sandys.Archbishop Sandys. The same year as Brewster's appointment, Dr. Sandys (pronounced Sands) became archbishop. He knew the state of the diocese, for less than twenty years before he had gone through it at the head of a royal commission, and presented a report showing its deplorable condition in regard to the clergy, and the fabrics. At the time of the death of Edward VI. Dr. Sandys was Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University, but unfortunately having preached a sermon in support of Lady Jane Grey he was for ten months imprisoned by Queen Mary, and being released on condition of leaving the kingdom he and his wife and son went to Strasburg, and elsewhere abroad, suffering great privation. When Queen Elizabeth came to the throne she appointed a commission to go through Notts, and Yorkshire to ascertain the state of the church buildings, the service books (which must be changed in the rejection of the Mass) the condition of the clergy in charge, and as to their loyalty, with notes as to where they were obstinate, the state of public morals, etc. The Commission consisted of two knights, a Doctor of Laws, and at the head, the report states, was that "excellent man Master Edwin Sandys, Doctor of Sacred Theology," who commenced the work in the parish church of the Blessed Mary in the Town of Nottingham, when prayers being ended he declared God's Holy Word to the people in the chancel, and then the commissioners went together to a suitably prepared place for their work, which was afterwards continued in the Chapter House at Southwell, and later in the parish church of Blyth. thence proceeding into Yorkshire. The spiritual state of the villages in Nottinghamshire was so sad that doubtless it would take several generations to remedy the evils disclosed.

Dr. Sandys became Bishop of Worcester, and was in 1570 translated to London, and in 1575-6 to York, being the sixty-third occupant of the see. Five years after his accession to the archbishopric Queen Elizabeth set her heart upon Scrooby Manor House as a royal residence, and without further ceremony sent the archbishop a lease to sign demising the manors of Southwell and Scrooby for seventy years at an annual rental for Scrooby of £40. The archbishop was stunned, grieved, pleaded and prayed with tears, protested and begged, that he might not be required to sign the document, and prevailed. On December 20th, 1582, four weeks after the letter to the Queen, the Archbishop gave a lease of the Manor of Scrooby to his eldest son Samuel, he then being at the Middle Temple, the term being for twenty-one years, and the annual rental £21 2s. 6d., but with the obligation to repair and uphold the manor house and chapel, bakehouse, brewhouse, the gallery connecting the hall with chapel, barns, stables, and other buildings, with the park, also a house newly repaired on the east side of the orchard, other houses in the little Court, the house at the east side of the great Court with chambers, rooms, etc, which house had been commonly used for the archbishop's offices. He gave a second lease of the Mills at Scrooby, at a rental of £11. 12. 2. He gave many other leases to his sons. "I am bound in conscience to take care of my family," he said, and he did so.

The Archbishop died in 1588, and there is a monument to him in Southwell Cathedral, being a recumbent figure in alabaster, and in front of the tomb there are figures of his wife, seven sons and two daughters. That large family presented one of the difficulties of his life. Having during his banishment been trained in the school of adversity to great economy in expenditure, he followed the same course when he became archbishop. He cared nothing about ostentatious display as some of his predecessors had shown. He dispensed with outward show, and preferred retirement. He appears to have been one of the principal contributors to the restoration of the old Palace at Southwell, where (Dickinson says) he almost constantly resided, and was the last archbishop that did so. The Archbishop's widow may after his death have resided for a time at the Manor House, but she died and was buried at Woodham Ferrers in 1610.

Sir E. Sandys. It is an interesting question as to whether Sir Edwin Sandys occupied the Manor House, and whether such occupation, if proved, applied to the chief house only, while the tenant occupied one of the subordinate houses and farm buildings. It would be gratifying if a period of occupation could be proved, for he was a worthy man, and notable, but looking at his active and busy life elsewhere I fear we must here be content to with a very limited range. When the Archbishop was transferred to York Edwin would be about fifteen years of age, and was by his father very wisely placed under the care and tuition of Eichard Hooker, the "judicious" author of the great work the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. His companion was George Cranmer, great-nephew of another Nottinghamshire Archbishop, and the three formed a lifelong friendship. The tutor shaped their minds as he was preparing his great work, in which in after life they assisted by notes, corrections, and suggestions and they applied to the State the laws that he applied to the Church. Edwin took the full course at Corpus Christi, but in vacations would probably spend his time at the old palace at Southwell, or at Bishopthorpe, where his younger brother George was born, or, when passing between these places, at Scrooby, which was a convenient halt between the two places, and very likely William Brewster the Post and he would ride together, and form a lasting friendship. He was made a Prebend of York Cathedral when he was twenty-one, and began his public career as M.P. 1586-93. Then he and Cranmer took an extended tour abroad, 1593-99, and compiled, "A view or Survey of Eeligion in the Western parts of the World," which was afterwards called, Europae Speculum, (or the Mirror of Europe.) He went to Scotland, and accompanied King James to England, 1603, when he was knighted; again became M.P. 1603-10. Appointed on the Council of Virginia 1607. "Sir Edwyn Sandys," says Sir A. W. Ward in a recent lecture delivered before the British Academy on Shakespeare and the Makers of Virginia, was the central figure of a most memorable chapter of British Constitutional history." "He possessed a large fund of common sense, * * * * very genuine moral courage, so that his political career as a whole did lasting honour both to his reputation and that of the party which acted with him." So says Gardiner, the historian of the period, who in his book "Prince Charles and the Spanish Marriage," devotes twenty-five pages of a stirring character to the men of Scrooby, and the Sailing of the Mayflower. Sandys' determined efforts to secure constitutional government so offended the King that he (Sandys) was twice imprisoned for his outspoken speeches, and when the Virginian Company wanted to appoint Sandys Treasurer and Governor of Virginia, the King exclaimed, "Choose the devil if you will, but not Sir Edwin Sandys!" They did, however, choose him, but put a figure-head nominally above him. Largely through his influence a patent was given by the Company to the exiles, showing his sympathy with them, and writing to Robinson and Brewster in 1617, expressing his satisfaction with their seven articles, he subscribed himself as, "your very loving friend." Sir Edmund A. Lechmere, Bart., has a fine portrait of him at Hanley Castle, Worcester, "and a mass of papers, awaiting examination." A copy of the portrait is given in Nash's "Worcestershire." He is also mentioned as "of Latimers," Bucks. His estate was at Northbourne, in Kent, in the church of which is a marble tomb with figures in relief representing him and his wife. He had it erected in his lifetime, but the Latin inscription was added afterwards. The Rector has kindly sent me a copy, and it states that he was "a man pre-eminently endowed with intellectual gifts, and distinguished in letters. He assisted in writing Europae Speculum; in Parliament he stood forth as the zealous champion of true liberty (but not of the license now too rife.)" He died in 1629, aged sixty-eight. He married four times, but none of his wives were from our locality.

The Sandy's family were remarkable in the positions they took. Sir Samuel (1560—1623) already referred to frequently sat in Parliament. Sir Miles (1563—1644) was created a baronet and frequently sat in Parliament. George, the seventh son of the Archbishop, travelled extensively, interested himself in colonial enterprizes, and wrote books of poetry, contemplations, translations, etc.

King James I., on August 16th, 1603, directly after his accession, wrote Archbishop Hutton that finding no royal residence near Sherwood Forest, "where he will often have to pass in his journeys between England and Scotland, he wishes to make an exchange with the see of York for the houses and manors of Scrooby and Southwell, which are conveniently situated for his forest sports." The houses, the king said, were "much decayed" and he promised to give full value for them. The exchange, however, was not effected.

In 1636 the Executor of Archbishop Harsnet applied for a royal commission to consider his petition for relief as executor, a claim having been made against the deceased's estate for £7,000 for dilapidations, of which £4,020 was for Ripon and Scrooby houses, the claim being more than the whole of the deceased prelate's estate, and he had held the office only two and a half years. He said the lands had been leased out, so there was only the bare houses unleased, which were in utter decay, and no archbishop had lived in them for forty or fifty years, and he prayed that they might be demolished. The Commission reported accordingly, and so we may conclude that the buildings became greatly reduced.

"Here within memory," writes Dr. Thoroton in 1677, "stood a very fair palace,a far greater house of receit, and a better seat of provision than Southwell * * * Archbishop Sandes caused it to be demised to his son Sir Samuel Sands, since which the house hath been demolished almost to the ground."

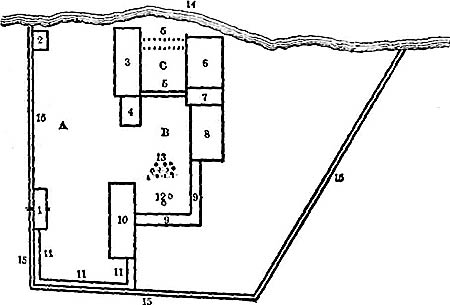

The Ruins. Dr. H. M. Dexter, D.D., LL.D. of the United States, visited Scrooby eight times between 1851 and 1887, in 1871 remaining six weeks, and by permission of Lord Houghton, then lord of the Manor, making thorough examination of the premises, including measurements and excavations, together with inspections of leases and documents at York. Apparently it was found impracticable to give dimensions of buildings, but below is a copy of the plan his son gives on page 227 of "The England and Holland of the Pilgrims," the book that gives the fullest and the most reliable information as to the early history of the Pilgrims, but reference must be made to that book for details.

A. |

Outer or greater court. |

|

8. |

House on east side of orchard. |

B. |

Inner or lesser court. |

|

9-9. |

Kitchen, pantry, bake-house, brew house, etc |

C. |

Open space, part of lesser court. |

|

10. |

House of chambers, offices, etc. |

1. |

Gate house. |

|

11-11-11-11-11. |

Barns, stables, sheds, etc. |

2. |

Great chamber. |

|

12. |

Fishponds. |

3. |

Great hall. |

|

13. |

Orchard. |

4. |

House adjoining hall. |

|

14. |

River Ryton. |

5-5. |

Galleries. |

|

15-15-15. |

Moat. |

6. |

Manor house. |

|

|

|

7. |

Chapel. |

|

|

|

The Old Inn. There is an old house fronting to the main street, and on the north of the approach to the Manor House, which deserves notice.

Originally timber framed, it has been from time to time so patched with bricks as to be hardly recognizable as an old house. It is now divided into three parts, one being used as a village Reading Room, another as a Smithy, and the rest as a Cottage. The large cellar, the quaint old cupboards, the smithy as the common room, and the location, caused Lady Galway to suggest, and I think rightly, that this was the ancient village Inn, and Mr. Marrison found inscribed on one of the beams, "1560," which was just after Queen Elizabeth's accession. It is possible that this was the "Cross Keys,'' mentioned elsewhere. Another suggestion is that it was Brewster's house. This, I think, very improbable.

In 1782 a report says, "It has still a good park, but the house is almost fallen to the ground."