SOME NOTTINGHAMSHIRE STRONGHOLDS.

By I. CHALKLEY GOULD, Esq., F.S.A.

(Read at the Nottingham Congress, 1906.)

AT various meetings of this Association it has been my privilege to say something about the remains of ancient strongholds in the districts visited, and I propose to follow the same course here; but fortunately for my hearers I need not detain them long, for Nottinghamshire is not rich in examples.

We may search the county through and find none of the grand early type we have seen elsewhere. We look in vain for a lofty precipice-protected promontory fortress, such as Comb Moss, near Buxton; though, could we see Nottingham Castle site, as it was in its primitive days, we should find the same idea of defence of a somewhat similar position.

We cannot find such a hill-fort as Mam Tor, crowning the ridge of the "Shivering Mountain," near Castleton, in Derbyshire, nor one like High Wincobank, near Sheffield.1

Even neighbouring Leicestershire, though of much the same physical character as this shire, is richer from our point of view, for there I was able to picture to you Burrow Hill, with its remarkable entrenchments, more striking than those of anv camp of the like class in this county.

Why is Nottinghamshire so poor in remnants of the earliest types of earthwork?

Partly because the district afforded few of those bold heights such as Celtic man loved to construct their camps of refuge upon; and perhaps I cannot do better than quote a few words from Mr. Stevenson's Introduction to his account of the ancient earthworks, in the Victoria County History of Nottinghamshire—a forthcoming book which Nottinghamshire folk will do well to buy, both for its present interest and for its future financial value. Mr. Stevenson says: "Neither physically nor strategically do the gentle contours of Nottinghamshire provide sites for those great hill-fortresses to be found on the crests of the hills in many other counties."

With few exceptions, its natural features did not lend themselves to fortification. This was compensated for in the Pennine Range of Derbyshire, on the west, which overlooked the comparatively level surface of this county, and formed a barrier to the invaders of the territory of the Coritani: a tribe which occupied approximately the present shires of Lincoln, Nottingham, and Leicester.

Forest and swamp occupied a large part of Nottinghamshire. Remains of old woods are extant in the hays of Birkland and Bilhagh, to the north of Ollerton and Edwinstowe; while in the north-eastern extremity the swamps that intervened between the northern boundary and the Isle of Axholme were almost impassable.

Of promontory forts (Class A in the Scheme2) Nottingham Castle site, already mentioned, was the chief representative, but probably Castle Hill, Worksop, and Combs Farm Camp, Farnsfield, were of much the same type.

Of hill-forts (Class B), as has been said, we have no Mam Tor or Wincobank, or even a Burrow Hill, though there are a few earthworks of the same character, but poorer in the height and dignity of their ramparts and in the depth of their fosses.

Woodborough, Notts.

Oxton, Notts.

Fox Wood Camp, in Woodborough parish, is placed on a high plateau, so boldly conspicuous that we forget for a moment that the ramparts are but 7 ft. to 10 ft. above their fosses. It is an interesting stronghold, and appears to have been added to and strengthened internally (possibly by Roman hands), subsequently to the erection of the outer encircling rampart.

Unfortunately, at some past period, the works on the east have been utterly destroyed, and the whole camp is in a wood densely covered with undergrowth and tall weeds. It has often been said that where stinging-nettles are, man has lived. Man must have been pretty thick on the spot if the beds of big nettles in this lonely wood are true evidence.

I will not occupy time by mentioning each of the other strongholds of this type, but there is one example I crave your permission to dwell upon for a few moment; for no early stronghold in Nottinghamshire appealed to me so strongly as Oldox, or Hodox, Camp, in Oxton parish. Far away from human habitation is a lonely comb in the hills, and therein, nestling below the surrounding summits, is this camp of our Celtic forerunners.

A raised causeway, made by much labour, leads to its southern entrance, and a deeply-sunken road leads from over the ridge of the; hill on the eastern side to the same point. These are sufficient evidence of the great importance of the stronghold. Three tiers of ramparts rise one above the other on the sharp .slope of the eastern side to a total height of about 45 ft. above the hollow of the comb; elsewhere the camp was defended by a double rampart, with a fosse between.

Much might be said of this remarkable camp: its trick, or sham, entrance on the south, its real gateway on the north, approached by an easily-defended fosse all the way from the southern point, its artificial elevation, and the spot from which thousands of tons of earth were probably moved to secure this increased height and level surface; the wondrous view from the adjoining look-out hill and from its twin, further on the north-east; but time presses, and I fear to weary anyone but an earthwork enthusiast.

Passing from these early fortresses, essential to the life of Celtic man in these islands, we come to those of the days when imperial Rome dominated Britain.

Carcolston, Notts. Reputed site of Margidunum.

But of defensive works of that age, Nottinghamshire possesses only poor traces. What is left of Margidunum? Just a rectangular fragment, with the characteristic berm, or terrace, between the rampart and its fosse.

Yet this stronghold was of no mean importance to the Roman rulers, for it guarded the fosse-way which cuts through its area. It is easy enough to get round the site now; but we must picture to ourselves dense woodland or impassable morass, stretching far on either side of the great trackway, to realise the importance of this station in checking the advance of a body of foes.

There are fragments of a few other camps which may also be Roman, but they have been for the most part swept away in the advance of agriculture, or by the agency of mines, quarries, and buildings.

And what have we of the works of those sea-rovers who followed on the wreck of Roman Britain? Neither Saxon nor Dane has left a certain trace, save only the "English Borough" which the buildings of busy Nottingham have nearly obliterated: and it may be that some of the simple homestead moats, to which reference will be made, were dug in the stormy days of the ninth and tenth centuries, just as they were in later times.

We must pass to the earthworks known as "mount and court strongholds" (Classes D and E in the Scheme). I cannot here enter into the discussion of the date of these works. Suffice it to say that opinion in the archaeological world is settling down to acceptance of the theory of Norman origin, or of construction under Norman influence, though sometimes the feudal lord appears to have utilised an existing tumulus or mount, or a protected height; and works akin, though not exactly similar, are found in parts of Wales and Ireland, where the evidence of Norman rule and influence is questioned.1

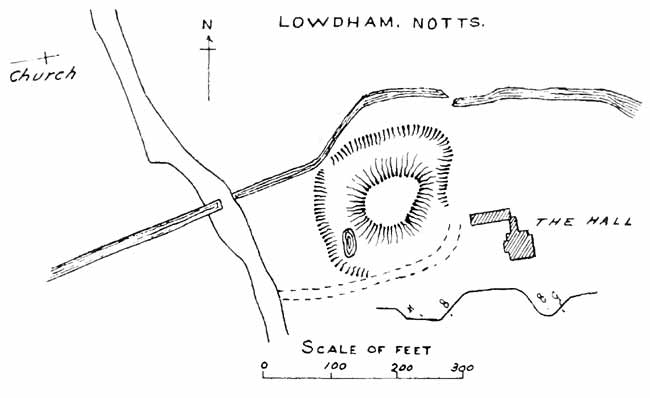

In its most simple form (Class D), we find but a mount trenched round. Such a work was the mount above Cocker Beck, at Lowdham, and one or two others in the county. I exhibit a plan of the little work at Lowdham.

1 Now happily saved from destruction by the appeal to the Duke of Norfolk, in which this Association took no mean part.

2 The Scheme referred to was published by the Congress of the Archaeological Societies.