< Previous

Cornelius Brown: The Nottinghamshire Historian

By Douglas P. Blatherwick

[It is proposed in future issues of this magazine to deal with the works of the late Cornelius Brown. Mr. Blatherwick, the contributor of this article, is a grandson of this illustrious writer.—Editor.]

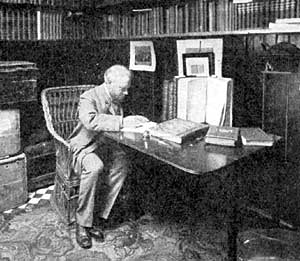

A typical portrait of Cornelius Brown in his study reading the proofs of the History of Newark.

VOLTAIRE laid down a test of greatness when he said, "With me, as you know, great men come first, the military heroes last. I call those men great who have distinguished themselves in useful and constructive pursuits; the others, who ravage and subdue provinces, are merely heroes." If we may accept this rule as a true test of greatness, then Cornelius Brown was not the least of Nottinghamshire worthies.

Cornelius Brown was born at Lowdham, on March 5th, 1852, a Notts, man by birth, family, and residence alike. His early days were spent in the village, where he attended the local school, until he was old enough to mount his pony and ride to the ferry that took him across to East Bridgford, where he attended Mr. Clough's private school. His father, the village baker, no doubt intended his son to follow in his footsteps, but young Cornelius had already shown some aptitude for journalism, and encouraged by his mother, he made his way to Nottingham and became apprenticed to The Nottingham Guardian. He taught himself shorthand and soon made his way to the front rank in the county by sheer merit and ability. The experience gained in those early days on the staff of The Guardian had a lasting effect on him, it also provided him with a limitless fund of reminiscences of the celebrities who visited the county town and of the great political fights of the period, that always made his conversation interesting. He attended the Cutlers' Feast at Sheffield each year as the special reporter for The Nottingham Guardian and The Sheffield Daily Telegraph.

Mr. Potter Briscoe encouraged him to persuade the Editor of the paper with which he was connected to begin a Local Notes and Queries column. This he did, and in 1874, at the age of 22, from a selection of the material used in those columns he published his first book, "Notes about Notts."

In the same year he was persuaded to accept the Editorship of The Newark Advertiser. From the day he began until he died in 1907 he made it his duty to see that The Advertiser held to the highest traditions of journalism, and in this he in no way failed. The standard that he set for his paper was a high one, the prestige was never lowered by petty back-biting. He had ideals, he had convictions, and was no laggard in the fray. On his death the Editor of The Newark Herald paid this tribute to his memory, "As we knew Mr. Cornelius Brown, he was a specimen of an English gentleman, strong in character, and genial in temperament. As a journalistic colleague, the writer has always been met by him with that 'debonair' which is characteristic of the old school ... he was always ready with a kindly smile and a genial word, and if necessary, a helping hand."

The last leading article that Mr. Brown ever wrote must have been characteristic of the standard that he set. It begins thus, "On another page, in accordance with the practice of The Advertiser to report with absolute fairness both sides, we give a tolerably full account of the Liberal meeting on Monday night at Newark." After which, in nicely chosen phrases, he carefully unpicks the Liberal cloak of arguments. "As a politician he exercised much tolerance, and knew how to respect those who held views which did not coincide with his own."

In achieving his ends he found the best in the men with whom he worked; he knew of what they were capable and succeeded in bringing out the best. His own men loved him. Nat Gould, the most famous perhaps of those who passed through his hands, wrote, "I often look back in wonder to those days. Mr. Brown never exactly taught, he guided. He knew what a man was capable of, and imperceptibly beckoned him along the road by holding out some reward for exertion at the halting places. He always was willing to listen and to give advice which if followed proved valuable. I remember on one occasion—it was my first year, I think—when he asked me to do the descriptive matter for the opening of Nottingham Castle by our King, then Prince of Wales, saying to him I was hardly competent to fulfil such a task to his satisfaction. 'I know you can do it well,' was his reply, no more; he relied upon me "to do it well.' Another instance. During my first week he sent me to take notes at a meeting. He read the paragraph. Comment : 'Where did you sit ?' 'At the back.' 'Ah, I thought so. Now, next time go up to the front. You'll know the difference, so shall I.' Then came words of cheer and encouragement that spurred me on, and again he guided me with that firm hand, as delicate as a 'silken thread' was the cord it held."

A general idea of his character will have already been gained from the extracts I have chosen. He was a jolly Victorian gentleman. It was a rule of his life that he never hurt anybody or made an enemy if he could possibly avoid it, so that in addition to his friendships with Dean Hole, the late Earl of Winchelsea, the Hon. Harold Finchatton and other famous men of the past, he could count as friends those with whom he radically disagreed. When he died, Ald. Thos. Earp wrote, "Few can bear witness to such a sad event with a higher sense of appreciation and esteem than I shall entertain for my dear friend as long as memory lasts." Those are the words of the leading Liberal about the centre pin of Newark Conservatism, in the days when feeling ran high. He had a ready fund of wit and humour and the tears would run down his cheeks as he repeated some droll story so that everybody would have to laugh with him. He had few rivals in the art of after-dinner speaking; the notes for which he always scribbled on his shirt cuffs. And yet withal he was never a man to advertise himself or his family. Indeed it was only the pressure brought to bear upon him by his own workmen that any mention in The Advertiser was allowed to appear of his own daughter's wedding. In private life he was a "good sport," jovial and easygoing.

Mr. Brown was a keen fisherman, and there are many still who can remember seeing him standing with rod and line at Long Bennington catching "whackers." There is one delightful story told by one of his friends, that on one occasion after he had announced that he had caught four "whackers," he was greatly distressed to discover that an inquisitive cow had carried off his complete catch in her hoof.

But neither as a fisherman, a photographer, a Mason, a politician, nor an Editor will the name of Cornelius Brown be remembered. He was above everything a historian and antiquarian. There was nothing easy-going in his work; he sought high and low for information relating to his own county, and no fact however small was too much trouble to seek out for the perfection of his work. He travelled all over England in his quest and searched many an old file of dusty deeds and papers.

Mention has already been made of his first book, "Notes about Notts." In 1879 "The Annals of Newark" were published. One of the things that he treasured most was the proofs of this book, some pages of which were revised by the Rt. Hon. William Ewart Gladstone, and which bear the handwriting of the great Victorian statesman.

The "Worthies of Nottinghamshire," published in 1882, is a remarkable compilation of the histories of the many famous natives of this county. "I felt convinced that not only was there ample scope and abundant need for such a work, but that it would be most acceptable to those who are justly proud of their county, and feel that, whether Nottinghamshire be regarded commercially or historically, the association with which the ties of birth give us is as 'the citizenship of no mean city.' "With so many noble names inscribed upon our roll of honour—Nottinghamshire assuredly deserves to possess a county biography—a study of these lives, while it will make our Nottinghamshire youths feel more interested in their native county, more familiar with its historic scenes, more proud of its classic ground, will also show them that, though it may often be hard to climb

"The steep where Fame's proud temple sits afar,"

the summit is not inaccessible to those who, with a brave heart and clear conscience, press on manfully and nobly, ever remembering that whatever distinction may be gained "'tis only noble to be good" that "the purest treasure mortal times afford is spotless reputation," that those gain the highest triumphs who can conquer themselves, and that whether in the seclusion of the quiet life or amidst the glitter of pomp or the pride of victory

"He most LIVES

"Who thinks most, feels the noblest, acts the best."

With this quotation of Philip James Bailey, Cornelius Brown introduced to posterity the lives of Nottinghamshire's greatest men.

The next two books that he wrote were not connected with this county. They were, "An appreciative life of the Earl of Beaconsfield," and "True Stories of the Reign of Queen Victoria."

In 1891 a history of Nottinghamshire appeared, which had it been published to-day might well have enjoyed the popularity of Mr. H. V. Morton's "In Search of England." After this he set to work to compile his masterpiece—The History of Newark. This self-imposed task occupied all his spare time for fifteen long years, and in his own words: "Newark is worthy of the book, and if the book prove worthy of the town, my ambition and reward are alike satisfied." The history comprises two volumes with over 700 pages of letterpress and about 300 illustrations. Each century of Newark's history is portrayed in detail from knowledge gained from original sources. The labour entailed must have been enormous, but it was a labour of love. He wrote, "Those local historians who enter on such an enterprise do not usually look for financial reward, and if they do they usually look in vain. The recompense comes in other ways, and no doubt the author of this history of Newark will for the rest of his days feel a sense of satisfaction in the thought that he has been enabled to set forth the historic fame of a town that incited and justified his best efforts."

With the publication of this work, however, there is a touch of tragedy. A day or so after he had returned the last proof to the printer, Mr. Brown was taken ill and within a few hours he passed away, on November 4th, 1907, his finished masterpiece unseen.

He was intensely fascinated in his work, but never failed to interest other people. Histories packed with facts can be deadly dull to the average reader. The art of the historian is in no way an easy one to acquire. Some few, like Trevelyan and Justin Macarthy, have succeeded in making history live. Yet the works of Cornelius Brown are never dull; his style suited the work that he undertook and his words were carefully chosen, revealing a thoroughness that was typical of the man himself. As a "local" historian his work is of an exceptionally high standard.

His research work was recognized by the Society of Antiquaries who elected him a member of that body in the year that he died. His nomination papers were signed by many of the leading archaeologists of the day including the Earl of Liverpool, Sir Benjamin Stone, Canon Greenwell and Mr. Leach of the Charity Commissioners. He was recognized as one of the leading authorities in the Midlands and as such was constantly being consulted. As vice-president of the Thoroton Society he contributed much valuable material to their Transactions and whenever the Society visited the district of Newark he generally acted as guide and lecturer in his own inimitable way.

Such was Cornelius Brown. He was a man who played many parts, and played them to the best of his ability. When he died he was preparing to study for the Bar, and no doubt had he lived he would have succeeded in that too. The words that he wrote as an introduction to his "Worthies of Nottinghamshire" expressed the ideals of his own life.

< Previous