< Previous

The strange history of London Road Station

By Stephen Best

Near the south-western edge of Sneinton lies a building which recalls the rivalry between nineteenth century railway companies, gives a glimpse of what might have been at a famous London terminus, and was the setting for one of the most bizarre crimes ever committed in Nottingham.

The old London Road low level station is now the main British Rail parcels dept in Nottingham, but its opening in 1857 as the Great Northern Railway's independent passenger terminus in Nottingham put an end to a running battle which had lasted for several years. In 1846 a company with the ponderous title of the Ambergate, Nottingham & Boston & Eastern Junction Railway received Royal Assent for its bill in Parliament. This allowed the construction of a railway from Ambergate, through Nottingham and Grantham, to Spalding and Boston. It was decided to begin work with the line from Grantham to Nottingham, and this section of railway was accordingly laid from Grantham to Colwick. A junction was made here with the Midland Railway's Lincoln line, and running powers were negotiated with the Midland to enable the Ambergate Company’s trains to run over M.R. metals from Colwick Junction to the Midland Station on Station Street. The line opened in 1850, with both the Great Northern and the Midland seeking to work the traffic for the Ambergate Company, but in 1851 the G.N.R. secured the job. Thus Ambergate Company trains, hauled by Great Northern locomotives, were using the Midland Railway's station. Such a situation was obviously fraught with diplomatic difficulties, and in August 1852 matters boiled over when the Great Northern decided to advertise an express train from King's Cross to Nottingham via Grantham, which reached Nottingham in less time than the Midland's own London expresses. This proved more than the M.R. could take, and in a celebrated incident the engine of the first such train to arrive at Nottingham was hemmed in by Midland engines, and shunted off to a shed, The rails were taken up, and the intrusive Great Northern locomotive remained a prisoner for seven months. The Midland claimed that the G.N.R. was infringing the running powers agreement made with the Ambergate Company, while the Great Northern was adamant that the Ambergate Co. had hired the engine, and was free to do what it wished with it. At the subsequent legal proceedings the court found in favour of the Ambergate Company, whereupon the Midland responded by obstructing the Ambergate's through traffic, obliging the company to carry its goods traffic to Colwick by cart. Clearly things could not go on like this for long and in 1854 the Ambergate Co. obtained powers which enabled it to lease all its effects to the Great Northern Railway for 999 years.

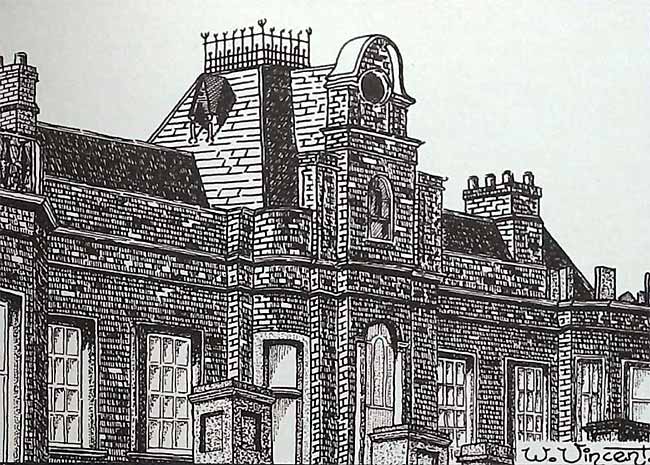

FADED GRANDEUR - BUT THE ELEGANCE REMAINS.

The G.N.R. wasted no time in securing its own access to Nottingham. Instead of using the Midland line from Colwick, it built independent tracks almost parallel to it. Great Northern traffic was to approach Nottingham on an embankment, crossing Meadow Lane and Trent Lane by bridges, and dropping down to the new terminal station in the East Croft. The junction at Colwick was eventually removed in 1866, to be reinstated almost a century later, in 1965, so that Grantham line trains might use the Midland Station once again.

The architect chosen to design the Great Northern station was Thomas Chambers Hine of Nottingham. T. C. Hine was one of the most successful architects in the East Midlands; born in 1813 he made an indelible mark on the townscape of his native place. He built a house for himself on Regent Street, off Park Row, and designed many houses in that street, on the Ropewalk, and in The Park, where he was responsible for nearly a third of the houses built.

Hine played a leading part in establishing the monumental quality of the Lace Market, designing the huge warehouse on Stoney Street for Adams and Page, and laying out Broadway, the short street between St. Mary's Gate and Stoney Street, which with its cunning S bend in the middle looks like a tall cul-de-sac when seen from either end. Hine was later to design, among other buildings, the Coppice Hospital on Ransom Road, All Saints' Church, Raleigh Street and St. Matthias' Church, Sneinton. Probably his best known work was the restoration of Nottingham Castle from a burnt out shell to be a museum and art gallery.

It is likely that T. C. Hine's commission to design London Road Station came through his connection with the Birkin family, who besides owning much of Broadway had financial interests in the new railway companies. Hine was asked to work on several of the stations on the Grantham line, and designed those at Radcliffe-on-Trent, Bingham, Aslockton and Elton & Orston.

His new station in Nottingham was reached from the Flood Road (now London Road) by a bridge over the canal. The main frontage faced north, and though not especially large, was an elaborate and interesting composition.

A central feature was the stone porte-cochere, under which cabs could set down passengers without their getting wet. This was topped by a handsome balustrade, with a Venetian window above, a tall shaped gable and a slated pyramid roof ending in a decorative iron crest. The range of buildings facing the Flood Road featured a row of round-headed dormer windows and another entrance. The whole was set off by stone quoins at the angles, parapets with decorative brickwork and splendid chimneys. The Nottingham Review of October 9th, 1857 described the new station, noting that the booking office was flanked by first and second class waiting rooms on each side, and that above these were the 'boardroom and apartments for the secretary and other officials'. The pyramid roof housed a muniment room and the west range contained parcels offices, rooms for guards and porters and a house for a railway official. 'Within the building' continued the Review 'at the north west angle, is a small but convenient refreshment room'.

Originally there were two platforms, one for arrivals and one for departures. The all-over roof of the station afforded excellent shelter at the buffer-stops end of the terminus and there were two middle roads between the platforms for use as carriage sidings. The cost of the new station was £20,000.

Eight years after the opening of the Great Northern station T. C. Hine had a chance to make his name with a railway building of major importance. In 1865 the Midland Railway staged a competition for the design of the Midland Grand Hotel at St. Pancras Station. This was to be the most luxurious hotel imaginable, so as to attract wealthy industrial magnates from the Midlands and the North to the new London terminus. Hine was not in the original list of architects invited to enter the competition, but with two others was asked later on.

Hine and his partner Evans accordingly entered and drew up a design which it was estimated would cost £255,000 to build. Hine's entry was not placed in the first four and all details of it are lost. Perhaps it is not too fanciful to think that in his drawings for St. Pancras T.C. Hine would have included the trademarks of his buildings here in Nottingham. Instead of Scott’s Gothic extravaganza, there might have been echoes in the Euston Road of the Lace Market or London Road Station.

The first timetable published after the opening of the Great Northern station in 1857 shows seven trains a day leaving Nottingham for Grantham, with six workings in the opposite direction; extra market trains were run on Saturdays. Much additional traffic came to the station in the 1870's and 1880's, with the opening of new lines. The G.N.R. branch to Pinxton was opened to passengers in 1876 followed in 1878 by the lines from Awsworth Junction to Derby Friargate, and from Bottesford West Junction to Newark. During 1879 the Great Northern and London & North Western Joint line from Saxondale Junction to Welham Junction came into use, allowing through trains from Northampton and Market Harborough to run into London Road station. The L.N.W.R. was responsible for operating these trains, bringing its own locomotives to Nottingham to add to the variety of engines which delighted the Victorian railway enthusiast. Then in 1882 the G.N.R. Leen Valley line opened from Basford to Newstead, in competition with the Midland Railway's line to the Nottinghamshire coalfield. By 1881 the station's two platforms had been increased to five to help cope with the increased demands upon it.

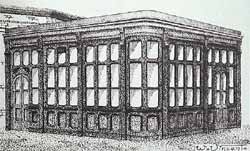

THE OLD REFRESHMENT ROOMS

THE OLD REFRESHMENT ROOMS G.N.R. trains to places such as Derby were still obliged to take a circuitous route through Gedling before turning west to head through Basford and Kimberley. The opening in December 1889 of the Nottingham Suburban Railway put an end to this state of affairs. The through journey was shortened by three miles, and new stations were provided at Thorneywood, St. Ann's Well and Sherwood to stimulate residential traffic. There was to have been a passenger station at Sneinton Dale but this never materialised. With the opening of the Suburban Railway the network of lines radiating from London Road Station was complete.

The opening day, December 2nd, 1889, was marked by an episode so ludicrous that it overshadowed the fact that the trains had actually started to run. For some time Mr. Edwards, the contractor who built the line, had been in dispute with the railway company, who had sought an injunction to prevent Mr. Edwards from interfering with the opening. The first train left London Road for Daybrook at 7.45 a.m. with a party of notables, including Mr. Edwards, on board. When the train reached Trent Lane Junction it was halted by a Mr. Colson, agent for Mr. Edwards. This gentleman was standing in the four-foot, waving a red flag, and he uttered a statement to the effect that the line was still in the possession of Mr. Edwards and that the train and its passengers were trespassers. Mr. Grinling, district engineer to the Great Northern, remarked that as the protest was a formal one, they ought to go on.

Mr. Colson, sticking to his post with a tenacity that one can only admire, retorted that he would move only if forced to. 'Upon this' said the Evening Post, 'the order was given to put the steam on the regulators and the engine moving, Mr. Colson was obliged to slip off the line but he placed the flag on the rail and the train ran over it'. At this point Mr. Colson fades from the story, having discovered one of the more disagreeable ways of passing a raw December morning at Sneinton. The footnote to this incident is worthy of the rest: on arrival at Thorneywood Station the tickets were checked and Mr. Edwards was reported to the railway authorities for travelling without a ticket.

1889 was a year to remember, as barely two weeks before this farce, an altogether more serious incident took place at the Great Northern station. On November 19th His Honour Judge Bristowe, judge of the Nottingham County Court, made his way to the station to catch the 5.40 p.m. train to Derby, in which he was proposing to travel as far as West Hallam, where he lived. As the judge was getting into a first-class carriage he was shot in the back at point blank range by a man holding a revolver. The judge was hurried to hospital, his assailant to the police station and for the next few months Nottingham's newspapers had a sensation on their hands, as a criminal tragi-comedy unfolded.

Strange to relate, the immediate cause of this murderous attack on Judge Bristowe was a set of false teeth. On the day of the crime the judge heard a case in which Wilhelm Edward Arnemann claimed the sum of £1.15s. from a Mr. Warriner for false teeth supplied. Mr. Warriner refused to pay on the grounds that the teeth did not fit and the judge agreed with him. Arnemann, full of resentment, followed Judge Bristowe to London Road station and shot him. He was heard to exclaim when seized by onlookers 'I have done him; I intended to do him; I could drink his blood'.

It was hardly likely that the press would display any sympathy for the perpetrator of such a crime and even before the trial a serious of blood-curdling news stories appeared Arnemann had come to Nottingham about 1884 from St. Petersburg, where he had practised as a dentist. In Nottingham he had a shop at 37 South Sherwood Street, but in 1886 fell foul of the British Dental Association. This body took action against him for practising as a dentist when he was not registered as such in Britain. Arnemann continued to trade as a manufacturer of artificial teeth, and at least two advertisements were placed by him in the Nottingham Evening Post. After the crime the papers found no difficulty in discovering witnesses prepared to describe Arnemann as 'a very peculiar man', who lived in a ramshackle shelter on the roof of his shop. The Nottingham Daily Express reported 'We understand that the prisoner - who is socialistically inclined, or at any rate of advanced political opinions - has stated that if he had committed the crime with which he was charged in Germany he would have been acquitted. He further added - this was to a sergeant of police - that what he had done was, in his opinion, to the benefit of the rising generation in England’.

Although it proved impossible to remove the bullet, Judge Bristowe survived and Arnemann was tried for attempted murder at Nottingham Assizes in March 1890. He refused legal representation but read out a long statement in his own defence. He accused the prosection of attempting to obtain false evidence, but, incriminating himself as he went on, said that the professional insults he had endured had preyed on his mind, that his soul was bleeding and his brain on fire. It must be likely that the wretched man was really unfit to plead but he was pronounced guilty and sentenced to 20 years penal servitude. The end of the affair was a terrible one, as Arnemann hanged himself in his prison cell. Judge Bristowe lived until 1897, although his health was impaired and he had to give up his legal career.

The eleven years following the opening of the Suburban Railway were the busiest in the life of the Great Northern station. The timetable for July 1898 reveals that on the average weekday no less than 65 passenger trains left the station, with 71 arrivals. Among the principal services were twelve journeys out via the Suburban Line, eight of these continuing to Newstead or Skegby. Sixteen trains a day ran to Grantham, with nine departures for Newark via Bottesford. Seven passenger trains ran to Burton-on-Trent via Derby, with a further six to Pinxton. The Joint Line to Market Harborough and Northampton had six services in each direction. Sunday traffic at London Road station was much lighter, with eighteen departures and twenty two arrivals.

This Indian summer was rudely ended by the opening of Victoria Station in 1900. From the new station the Great Northern ran out on a viaduct as far as Trent Lane Junction, and London Road High Level Station was opened only fifty yards from the 1857 station.

The transformation was abrupt; all G.N.R. services were re-routed to Victoria, leaving only the Joint Line trains, which were worked by the London & North Western. The 1910 timetable reflects the greatly reduced importance of the Low Level Station: just six trains on weekdays to Northampton, with five return workings and one from Leicester. After 1923 the circumstances were peculiar; the L.&.N.W.R. had become part of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway, while the G.N.R. had fallen into the London & North Eastern fold. There was thus the anomaly of L.M.S. trains being the only passenger services in a station built by a constituent company of the L.N.E.R. By 1938 the six trains each way had dwindled to five and London Road station was just a ghost of its former self. In May 1944 these few remaining passenger trains were diverted into Nottingham Victoria and the Low Level Station embarked on an even more humdrum existence. For twenty three years it handled general goods and parcels, until in 1967 it assumed a new identity as Nottingham Parcels Concentration Depot, an important role which it fulfils to this day.

DETAIL OF A CANOPY SUPPORT COLUMN

DETAIL OF A CANOPY SUPPORT COLUMNThe station suffered some accretions and alterations over the years. A large awning was erected along the London Road frontage and a new entrance was knocked through on that side. For years the roof was disfigured by a huge Great Northern Railway sign, and a general clutter of advertising boards did little to enhance the building. Now its grandeur is faded, but the elegant facade of T. C. Hine's prestige station is still thought by some to be Nottingham's best railway architecture. The passage of time has dealt harshly with the lines that used to run into the station and the only one on which passenger services survive is the route which caused the station to be built, the Grantham to Nottingham line.

To end on a personal note, the present writer was introduced to the dusty remnants of the station's splendour on an April day in 1952, when he was carried into one of the disused offices after breaking his leg while illegally train-spotting on the station.

< Previous