< Previous

This manly game:

The early days of cricket in and around Sneinton

By Stephen Best

It might be imagined that international sport had little connection with the Sneinton of the early nineteenth century, but among the local cricketers of the 1830s and 1840s was at least one player who was to achieve fame for his exploits overseas.

Probably our oldest organised popular game, cricket must have been fairly well established in Nottinghamshire by the year 1771, when Nottingham played Sheffield. It is generally accepted that the game first obtained a stronghold in the south of England, in Kent, Sussex, Hampshire and Surrey, before spreading erratically northwards. In its formative stages cricket was nurtured by various aristocratic patrons at their country seats. Before long, landlords of inns recognised the potential custom which thirsty cricketers and spectators represented, and the provision of cricket fields next to taverns became commonplace.

In its earliest days a predominantly rurally-based game, cricket spread to the towns as the population moved to them. Not everyone could find time to play: hours of work were long and working conditions arduous, but men who were self-employed, or at least able to carry out their work in hours regulated by themselves, came to the fore. In Nottinghamshire many notable cricketers were to emerge from the ranks of the framework-knitters, who mostly worked at home, and could put in several hours at their frames early in the morning and late at night so as to fit in their games of cricket.

By the 1830s, when it was recorded in the Sneinton area, cricket was recognisably the game we know today, but with some obvious differences.

The most striking of these was in bowling, where underarm or round arm deliveries were the rule, with the bowler allowed to raise his arm only as high as the shoulder. Most players wore tall beaver hats, and dressed in shirts with wide bow ties. Protective equipment such as pads and gloves was in its infancy, and it was with good reason that cricket was described in the contemporary press as 'this manly game.'

Cricket had been played for some years on the Forest (then also the home of Nottingham Racecourse) and in the Meadows, when on June 15th, 1832 the Nottingham Review published the following letter:

'Cricket Challenge: TO THE EDITOR OF THE NOTTINGHAM REVIEW.

Sir - Observing in Bell's Life in London, of last Sunday, a match at cricket to be played at Leicester, between the Junior Club of that town and the Junior Club of Nottingham, I beg, through the medium of your paper, to inform those clubs that the Rancliffe Club (of which I am a member) will play either of them for a sum to be agreed upon or they will make a match to play any other club in the three counties of Nottingham, Leicester or Derby, barring the first elevens of Nottingham and Leicester. Your obedient servant, Wm. Nix.

June 13th. P.S. - The Rancliffe Club may be heard of at the Rancliffe Tavern, Gedling Street, Nottingham.'

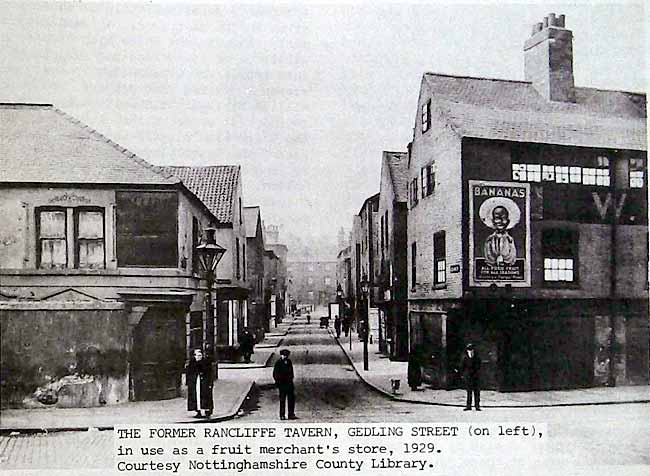

The writer of this letter, William Nix, was himself good player who had represented the Nottingham Old Club on one occasion. It is noteworthy that his challenge was for a game to be played for a stake, and it is apparent that the players of that time had a keen eye for a wager. Sometimes it seemed almost as if the game itself were of less importance than the stake money or the post-match banquet, as may be seen later. The Rancliffe Tavern, home of the Rancliffe Club, stood at the corner of Gedling Street and Finch Street. The northern end of Freckingham Street in the Sneinton Wholesale Market now occupies its site. The Rancliffe Tavern was to remain in business as a pub until its closure in December 1914. Thereafter the building was used as a fruit merchant's store until it was demolished about 1934 to make way for the new market.

The playing membership of the Rancliffe Club must have been a healthy one, since the Nottingham Review was able to report on August 30th, 1833 that 'a well contested game at cricket was played on Monday last, in the Lammas fields, between the married and single of the Rancliffe Club.' Fourteen played on either side, the married men winning by seven runs. William Nix, issuer of the 1832 challenge, was his side's top scorer. (This was, however, a less impressive achievement than it may sound, as he made only nine. Of his team’s total score of 66, no fewer than 35 were extras.) The Lammas fields were part of the unenclosed common lands surrounding the town, which were available for recreation for part of the year, and on which burgesses of Nottingham were entitled to graze sheep and cattle from Lammas Day (August 1st) until Martinmas (November 11th) each year. It is not possible to say exactly where the Rancliffe Club might have played.

There was a field only a hundred yards or so from Gedling Street which the 1845 Enclosure Award called the 'Meadow Platts Cricket Ground', and which was laid out in 1892 as Victoria Park. To state, though, that it definitely staged the Rancliffe Club's matches would be wishful thinking.

Ample evidence of the importance of cricket's social accompaniments in the 1830s is provided by a report of a match played on August 4th, 1834 between two lodges of shoemakers of Nottingham, in which Lodge No. 26 beat No. 102 by five runs. ’After play was over' related the Nottingham Review 'they sat down to an excellent supper, provided at the Nottingham Castle, Carter Gate, where conviviality was the order of the evening, and dancing and singing was kept up until a late hour.' The Nottingham Castle is of course still with us, though Carter Gate has become Lower Parliament Street, and the old building was replaced in 1968 by a modern one. The Review of October 10th, 1834 contains the first mention of Sneinton itself in a cricket report, but the details of the game take second place to the hilarious antics of one of the officials. 'On Thursday and Friday last, a match at cricket was played in one of the Snenton Lammas Fields, between the Snenton and Stoney Street Juvenile clubs, for a sum of money and a new cricket ball. A fracas occurred on Friday before playing commenced, in consequence of the Snenton umpire having disappeared, taking with him the ball, which was afterwards discovered to have been sold by him for 2s. and a quart of ale! This brief account raises several points of interest. The fact that the match was played in October suggests a degree of hardihood which few present-day cricketers could rival, yet games outside what we would regard as the cricket season were by no means uncommon. It would also be instructive to know the ages of these 'juveniles', who were playing for a stake, and to learn what exactly the fracas was. Did the two sides set about each other, or did they together vent their annoyance upon the delinquent umpire? Unhappily that must forever remain a mystery.

In September 1835 a new cricket club appeared in Sneinton. The Nottingham Review for the 27th announced that 'An interesting match at cricket is expected to come off on Monday in the fair week, in a field near to the Asylum, on the Carlton Road, between eleven of the Old Rancliffe Club and fourteen of a recently established club, held at the sign of the White Lion, on Carlton Road.' Shortly afterwards details of this match were given in the newspaper. At such an early stage in the White Lion Club's existence it is perhaps not surprising that its 14 men were beaten by the eleven Rancliffe Club players.

William Nix again did well, making 32, the highest score of the game. Among the White Lion players was Thomas Nixon, who later played for Nottinghamshire before moving to London. During his time there he was chosen four times to represent the Players against the Gentlemen at Lord's, then the greatest match of the cricket calendar. A slow bowler, Nixon also devised several items of cricket equipment, including a mechanical bowling machine for practice purposes. The White Lion Club was based at the pub whose successor has very recently been renamed Alfred's, and which stands at the corner of Carlton Road and Alfred Street.

The following week, on October 16th, 1835, the Review included details of a match 'played in a Lammas Field, near New Snenton, by eleven of Mr. Horatio Black's workmen, against eleven chosen from Mr. Olive Moore's and Mr. Newton's shops.' in this early example of a works cricket match the players came from the employees of three local lace markers, Horatio Black of Bond Street, Olive Moore of Haywood Street and John Newton of North Street. Moore's and Newton's shops, although the underdogs, won by eight wickets despite a valiant innings of 24 by Horatio Black himself, and the game's happy postscript was recorded in the paper. 'In the evening, the parties sat down to a most excellent supper, provided by Mr. Webster, at the Brittania New Snenton, and spent the evening with the utmost conviviality.'

A year after their defeat at the hands of the Rancliffe Club, the White Lion players suffered another trouncing. Representing Sneinton, they travelled to Basford to play a team from the Old Pear Tree.

Unhappily for the White Lion Club the Basford side won by an innings. Anyone trying to trace these early games has to contend with one highly confusing complication. In addition to the Rancliffe Club of Gedling Street there was a cricket club based at the Rancliffe Arms on Sussex Street. As the newspapers were inconsistent in naming the teams properly in their reports, and since a few players seem to have turned out for both clubs, it is sometimes difficult to work out exactly which side is playing. It does, however, seem sensible to identify the sides of the 1830s which included William Nix as those of the Rancliffe Club, Gedling Street, of which he proclaimed himself a member.

CHARLES BROWN, from a lithograph by J. C. Anderson. Courtesy Nottinghamshire County Library.

CHARLES BROWN, from a lithograph by J. C. Anderson. Courtesy Nottinghamshire County Library.Early in September 1838 the Nottingham Old Club eleven played 22 of the Town and County on the Forest. In the 22 was Charles Brown of the Rancliffe Club, a player who was to prove himself one of the most eccentric cricketers of the nineteenth century. In the second innings he made 27, earning the approval of the reporter. 'Charles Brown received the gratulations of the spectators . . . This is the first game of importance in which this young man has played . . . and the style of his batting, and admirable wicket, in our opinion, gave strong proofs of future excellence.' Charley Brown was described later in his career as 'a good batsman, an active fielder, by no means an indifferent bowler and an accomplished wicket keeper.' Such a paragon ought to have been the mainstay of any side, but the writer introduces a note of caution. 'All that he requires is a less restless temperament...' It was indeed this temperament that earned him the nickname of 'Mad Charley', a sobriquet richly deserved. He was a dyer employed in a local works, and legend has it that whenever cricket came into the conversation Charley would stir away vigorously, waving his arms to emphasise each point. The result of this excess of excitability was that not only the tubs of dye near his own, but also the men working at them, were apt to take on a rainbow hue. It was said that his employer, tiring at length of these disruptive interludes, told Brown that he must give up either his game or his job. Happily for cricket Charley left the dye works to set up on his own as a clothes cleaner. A year after his first big game, Charley Brown played a single wicket match against Henry Crook of Bingham, and favoured the onlookers with a further example of his eccentricity, this time in his style of bowling. He actually delivered the ball behind his back, so that although he bowled right-handed the ball was jerked out towards the unhappy batsman from somewhere in the region of his left shoulder blade. No wonder that the Nottingham Review described his bowling as 'to the astonishment of the spectators.' How Charley was able to achieve any degree of accuracy with this strange means of propulsion is beyond comprehension, yet stories of his prowess abounded. William Caffyn, a famous and long-lived cricketer of Victorian times, stated that he had seen Brown snuff out a candle flame with a bit of pipe-stem jerked across the room from behind his back. In 1846 Charley was a member of a cricket team largely composed of Nottingham men which visited Calais. Although this may seem a curious destination for a cricket team, it has to be remembered that there was a settlement of Nottingham lace workers there, and that the Nottingham Review was even on sale in the town. During this trip Charley played in a match at the Vauxhall Ground in Calais, totally bamboozling the opposing batsmen with his peculiar bowling. So celebrated did this feat become that it was immortalised in verse by Samuel Reynolds Hole, the Nottinghamshire-born clergyman and famous gardener: 'That England hath no rival Well knows the trembling pack, Whom Charley Brown, by Calais Town, Bowled out behind his back.'

In his wicket-keeping he was regarded by his contemporaries as 'clever as a monkey': unfortunately his dexterity was at times put to less than ethical uses, as when he perfected the knack of flicking off a bail when the ball had just missed the wicket, leaving the batsman thinking he had been bowled. There was also told a tale about a player who was terrified of dogs: he had just come in and was about to receive the bowling when there came an alarming growling and snapping at his ankle. Utterly unnerved, the batsman leapt out of the way and was bowled, only to see that the cause of his discomfiture had been Charley Brown playing a typical prank. The most prolific cricket artist of his day, J. C. Anderson, produced a coloured lithograph of Charley. He stands behind the wicket, bare hands extended, wearing top hat and bow tie, his solemn expression giving little idea of the impish nature of the man.

In following the mercurial Charles Brown we have, however, over-run the story of cricket in and around Sneinton. In that same issue of the Nottingham Review which described Charley's strange bowling in August 1839 is evidence of growing ambition in one of the local teams. 'Eleven of the White Lion Club are desirous of playing the same number of the Hyson Green, or Basford Clubs, for ten or twenty pounds a side.' It must have been difficult for any side to turn down such a public challenge and retain its dignity. The stakes, though, were high at a time when a farm labourer or a framework knitter could not expect to earn more than 11 or 12 shillings a week. Between members of the same club, however, matches were on a more relaxed basis, and in September 1840 two teams from the White Lion Club played 'for a supper.' This game, between sides whimsically labelled 'Under 30 years of Age' and 'About 30 years of Age', was notable for the presence of one of the great players of England. Joseph Guy was one of the most graceful batsmen of his day and a pillar of Nottingham cricket, celebrated in a remark of William Clarke, the great organiser of Notts, and All-England cricket in the first half of the nineteenth century. 'Joe Guy sir; all ease and elegance, fit to play before Her Majesty in a drawing room.' In this match though it was Guy's captaincy which caught the eye. 'The tact of Guy (one of the first eleven) in arranging the field, and his bowling, enabled the 'Young men' to beat their opponents.' The notion of playing for their supper obviously appealed to the White Lion cricketers, for the Nottingham Journal of September 10th, 1841 reports a similar fixture, this time between married and single of the Club. The single men won, said the press 'chiefly, no doubt in consequence of the absence of Nixon, one of the principal bowlers.' The Journal went on to describe the aftermath of this game: 'The players and rest of the Club sat down to a most excellent dinner, at doing justice to which, the married men were also bowled out by the single. Harmony prevailed until a late hour.' This happy atmosphere must have been a feature of White Lion games, as the following month a match played by the Club against Carlton was spoken of with warm approval by the Nottingham Review. 'The game throughout was played with that good feeling which always characterizes true lovers of the game. We regret we have not room for further particulars of this admirable match.' As the Review printed the full scores, it need not, perhaps, have been so apologetic. One A. Lacey made the very substantial score, for those days, of 41, and Thomas Nixon's bowling was considered 'first-rate.' Nixon it was who had previously earned for himself in the press the charming character of 'that promising and unassuming player.'

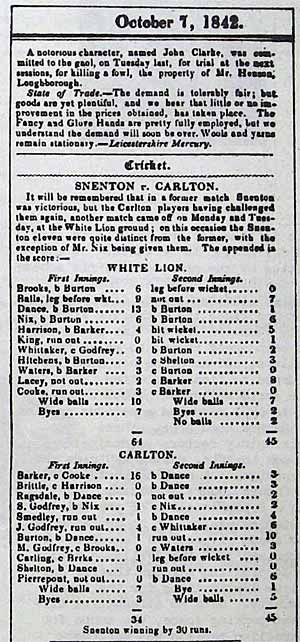

SCORECARD OF A MATCH played at Sneinton, 1842, from the Nottingham Review of October 7th.

SCORECARD OF A MATCH played at Sneinton, 1842, from the Nottingham Review of October 7th.1842 brought further indications that local cricket was in good health. A match took place at Trent Bridge in April between Town and County, and, said the Review, 'The White Lion Club, Carlton Road, and the Rancliffe Club furnished several players, conspicuous among the latter being 'Charley' Brown, who throughout the day gave proofs of being no mean player.' The White Lion Club was extending its horizons, arranging home and away fixtures with the Mansfield Senior Club. Early in October 1842 a match between Sneinton and Carlton was played at the White Lion ground. Apart from the fact that Sneinton won by 30 runs, the match was memorable for the home side's innings being opened by a player with the wonderfully appropriate name of Balls. Incredible to relate, the directories of the day also list among Sneinton residents Samuel Bats, lace maker of Bond Street, and J. Bails, sinker maker of Carlton Road, but to the great sorrow of this writer there is nothing to suggest that either was a cricketer.

Cricket may have changed in many ways since the 1840s, when the players of Sneinton were congratulated upon the sporting and friendly way in which their games were conducted. No cricketer, though, could aspire to anything better than this local match, played on Easter Monday, 1840. 'It being delightfully fine, the day's sport went off with the greatest eclat, the general impression being that they never enjoyed themselves better.'

Anyone writing in recent years on the history of Nottinghamshire cricket owes much to the pioneering work done on the subject by Peter Wynne-Thomas.

I place on record my indebtedness to him.

< Previous