< Previous

A LANDMARK REACHED:

One contributor looks back on 100 issues of Sneinton Magazine

By Stephen Best

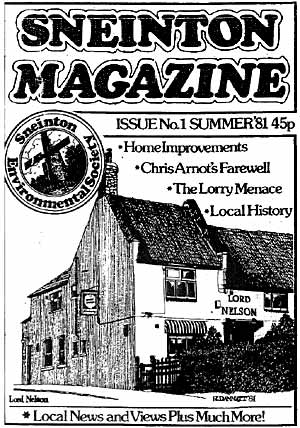

IT IS DIFFICULT TO REALIZE THAT more than a quarter of a century has passed since Dave Ablitt, then chairman of Sneinton Environmental Society, rang to tell me that the society was planning to launch a magazine.

Did I, he asked, think this was a good idea? Certainly I did, but with all the scepticism of a librarian who had seen more than one local periodical come and go, I privately gave it little chance of a long run. Dave’s next question was rather more challenging. Would I write an article for the first issue on some aspect of Sneinton history?

At the time I was in fairly good practice at doing this kind of thing, being in the routine of writing and recording a short weekly broadcast talk on local history for BBC Radio Nottingham. So I blithely agreed that a contribution would be forthcoming for the new Sneinton Magazine.

This first piece dealt with the Cattle Market, chosen partly because many people didn’t even know that it lay within the old Sneinton parish boundaries. Dave, no doubt after consulting Gilbert Clarke - initially there was an editorial and production team of three or four - pronounced himself satisfied, and in a moment of weakness I indicated that I was willing to put together an historical piece, or other Sneinton- related article, for each subsequent issue of the periodical.

This reckless promise assumed two things. In those early days brief contributions were the norm, so I concluded that the amount of writing expected of me would be within manageable bounds. And, as already hinted, my guess was that Sneinton Magazine would enjoy a life of about six issues before packing up. Besides, I thought, hardly anybody would hear about the launch of this praiseworthy venture, so any backsliding on my part would go largely unnoticed.

I reckoned, however, without Dave Ablitt’s tenacity, and his formidable skill in what these days we call networking. On this occasion he arranged to get the new magazine discussed on Radio Nottingham’s greatly respected and fondly-remembered weekly arts programme ‘Spectrum.’ Here he was interviewed by a man who played an honourable part in bringing local history to a wider audience in Nottingham. This was the late Tony Church, a great enthusiast for local history broadcasting, and notable producer of programmes in this field. It was an education to see and hear him at work.

During the radio discussion Dave stressed that the magazine would accept no financial assistance from any source other than the Environmental Society, and would thus retain complete independence of opinion. Tony reviewed the first number warmly, and I remember the frisson that ran down the back of my neck when Dave ended the interview by casually mentioning on air that he already had a promise from me of a regular article in future Sneinton Magazines. After such a public advertisement of this commitment, my fate was sealed - no chance of wriggling out of that one from then onwards.

So here we are today, with 99 further issues behind us, and it seems an appropriate moment for me to reflect on my part in the success or otherwise of the magazine. Has it all been worth doing? Of course it has. Could it have been better? Again, of course it could - with the benefit of hindsight I can see only too clearly how a number of my articles might have been differently constructed. But, in spite of disappointments and dashed hopes, there has been a matching number of satisfying achievements, and one feels privileged to have been involved with it all.

In recent years the number of active contributors has dwindled to a small, though fairly obsessed nucleus. We shall not be around for ever, and for me at least it is becoming increasingly difficult to find new topics to write about. If, however, the Sneinton community is sufficiently anxious for the magazine to continue, someone else will one day come forward to take it on. Let us hope so; Sneinton will no doubt continue to have its fair share of controversies and problems, and the community will need the independent voice that a community magazine provides.

Like some others who have written regularly in it, I had ceased to be a resident of Sneinton some years before the emergence of Sneinton Magazine. My family associations with the place, however, are strong. My great-greatgrandmother lived in New Sneinton in the middle of the nineteenth century, and my grandfather, born in Millstone Lane (now Huntingdon Street) married a Sneinton girl at St Alban’s church in 1897. Her mother, my Great- Grandmother Hardy, lived in Wagstaff Yard, off Pierrepont Street, until the time of the Great War.

My father and most of his seven brothers and sisters were bom at 13 Kingston Street, just across the road from the Albion Chapel - Dad’s birth occurring in 1903. Not only this, but between the wars my mother lived at 129 Sneinton Boulevard, from where she was married in March 1935 at St Christopher’s church in Colwick Road.

My earliest impressions of Sneinton were gained on childhood visits, two or three a week, during the war. At this time there were aunts, uncles and cousins to visit in Manor Street, Lyndhurst Road, and Lichfield Road, and in the fifties a younger branch of the family set up house in Ena Avenue. My cousins moved away, and my aunts and uncles all died between the late 1960s and 1980, the last Sneinton aunt surviving until I was past forty.

Even when I was very small the neighbourhood held a strong fascination for me. For a start, a bomb-mined church and a derelict windmill were something you didn’t see everywhere, and there was always a mysterious line of silent and forbidding goods wagons to capture the imagination, standing for years on the old Nottingham Suburban Railway bridge that crossed the Dale near Edale Road. Anyone who has persevered with the magazine over 25 years will know that the presence of a railway in the landscape has always quickened my interest.

Some people have asked how I choose Sneinton topics to write about. The answer is that these rather often seem to have chosen me and to have demanded an article. A photograph of a vanished building or street: a chance find in an old newspaper of the report of a death, a fire, or local reaction to a political or national event; any of these can start the process. Friends have lent or given pamphlets or ephemeral publications with the words: ‘I don’t suppose this will be any use to you?’ Several of these have lit the blue touch-paper over the years. And then there are inscriptions on gravestones, many of which have set the ball rolling for what would eventually become an article about some aspect of Sneinton history.

If something or somebody in Sneinton’s past is interesting enough for me to spend time in ferreting out the relevant facts, then I hope it will also prove sufficiently interesting for somebody out there to want to read about it. I don’t do requests, so have occasionally had to decline to write about a topic suggested by a correspondent. In most of these instances, the job would in fact have amounted to researching other people’s family trees. There also remain two or three topics on which the editor of Sneinton Magazine would have liked me to write, such as Pearson’s Fresh Air Fund, and local railway accidents. In spite of repeated nagging on his part, I have unfortunately failed to find any particular Sneinton connection with the first, and the nearest railway mishap I have traced occurred several hundred yards outside the Sneinton boundaries. If shortage of copy becomes desperate, however, the latter may indeed one day find a place in the magazine.

Several local subjects have been fully dealt with by others. Some of the most famous Sneinton figures, like George Green, General Booth, and Bendigo - though the last-named really didn’t have very much to do with Sneinton - have all been written up in detail by people more knowledgeable about them than I, so I have steered clear, and concentrated on topics that haven’t been covered before.

Someone once asked whether I had possibly written about Sneinton with all the enthusiasm of a man who has never had to live there. This was a fair question, which I refuted by pointing out what has already been hinted at: namely, that I was once a resident here. When first married I lived in Dale Grove between 1962 and 1971. This experience did nothing to put me off the neighbourhood, but it did give me a more realistic view of Sneinton than I had previously gained as a visitor. Once again, one has regrets. I often wish I had paid closer attention to some particular bit of Sneinton which seemed to me then mundane, or even downright scruffy, but which is now tantalisingly and irretrievably lost.

Back to gravestones, and especially those in Sneinton churchyard. This was in a sadly dilapidated state in the early 1980s, and trustees of the local Barbara Dalton Environmental Charity (of whom I was one) resolved to promote its tidying-up and general renovation. Many gravestones had over the years been displaced from their original sites, and were lying flat on the ground, no longer serving as grave markers; a number of these had been removed from their proper locations as early as the 1930s. Under professional architectural supervision, they were reset upright along two sides of the churchyard wall. Though not a perfect solution, this very necessary rescue operation did save many stones from further injury from bikes, roller skates and skateboards. And it is worth noting that very few of the stones fixed to the walls have subsequently been damaged.

Throughout the eighties and nineties, these graveyard memorials have proved a rich source of historical articles. They include inscriptions in memory of such disparate personalities as prominent industrialists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: members of a landowning family from the opposite end of Nottingham: a youth who died in a playground tussle at a reform school: a Nottingham dancing master: a Sneinton beerhouse keeper, who as a soldier had seen service in Corfu: and a local blacksmith. Of the industrialists, one died close to home, having been taken ill at the Flying Horse; another died in the booking office of a London station. One youth’s family had recently moved to Sneinton in the vain hope that the country air here would assist his return to health: one poor young woman died two days after her marriage. Many others, just as colourful, could be listed.

Memorial stones in other cemeteries in and around the city commemorate people with Sneinton connections who have been celebrated in the magazine. One was a painter and poet; a second a prosperous shop owner and Mayor of Nottingham, and another a balloonist whose last ascent ended in tragedy.

In the course of writing about people associated with Sneinton, I have in turn felt for them affection, admiration (sometimes grudging,) sympathy, pity, and only very occasionally downright dislike. These characters have included some almost-forgotten folk who have added light and shade to Sneinton history. Here are the good, the bad, and I daresay the ugly. Readers may have had to make up their own minds as to which were which.

There is, I think, still a dangerous temptation to sentimentalise the past, and to dream up the rosy glow of a time and place in which no one swore, stole, behaved violently, committed a public nuisance, or forgot his rightful station in society. Alas, Nottingham newspapers since the latter years of the eighteenth century repeatedly give the lie to this illusion. So, in writing about Sneinton I have always tried to tell it how it was. Riot: arson: bullying: hanky-panky in the park after nightfall: desperate poverty: insanitary and disease-ridden homes: ill-behaved children, and even quarrelsome clergymen - all these and more have featured in Sneinton articles in these 100 magazines.

And, of course, there has been comedy. It has been fun to chronicle the vicissitudes of Victorian and Edwardian excursionists on days out from Sneinton by bicycle or horse-brake: gamesmanship and skulduggery in early cricket matches here: and the drunken antics of a local steeplejack.

Any contributions made by me have been only a small part of the bigger picture of Sneinton reflected in the magazine. Historical articles are all very well, but much of Sneinton Magazine’s most important work has been in promoting such major programmes as the Sneinton Railway Lands redevelopment, and in the valiant, though ultimately unsuccessful scheme to establish an industrial museum in the former London Road Low Level Station. Other people were better qualified to write about these projects, and deserve all the credit for them.

Living as I do, some two or three hundred yards beyond the city boundary, I have not usually commented on controversial subjects like planning decisions, and current social developments in Sneinton - these seem more appropriately dealt with by magazine contributors who also live in Sneinton. Sometimes, though, this self-imposed rule has proved impossible to maintain, and indignation or impatience has pushed me into print on such topics.

It has been good to discover that the magazine means a lot to many of its readers. From time to time, however, everybody connected with Sneinton Magazine has wished that more people in Sneinton would purchase it. It has been scant consolation to be told by a lady on the bus that she always buys the latest issue of the magazine at the Post Office, and finds it so absorbing that she passes her copy around a circle of twelve friends for them to read. Thanks a lot, madam; if only six of these had bought their own copies we would have been in a better financial state.

Although locals have sometimes seemed unresponsive to the magazine, it is gratifying that members of other local amenity societies, and even those able to influence council decisions, have often taken note of what it says. But for me, the most warming response has been from people who no longer live here in Sneinton - people who haven’t done so for decades, but who still regularly obtain and read the magazine.

I have received letters from, among other places, Lincolnshire, Cumbria, Gloucestershire (this a very appreciative Sneinton exile) and Scotland, and last year received a follow-up enquiry about a magazine article from someone in Oregon who had picked it up via the Internet. My own cousins in Canada (a one-time Sneintonian who subscribes to the magazine) and in Australia are regular readers, and I am delighted that a magazine sent to Australia goes the rounds of a small colony of Nottingham exiles in Adelaide. At that distance, they are excused from purchasing a copy each.

Perhaps my most touching moment occurred one summer afternoon about ten years ago. I was sitting in the garden when the doorbell rang, and a native of Sneinton introduced himself. Long resident on the other side of the world, he was an annual subscriber to the magazine, and was on a visit from New Zealand to friends in, if memory serves, Bunny or Ruddington. From there he had come up to Carlton by bus, to say how much he had enjoyed the magazine articles and to chat. He can have had little idea of how much this means to a writer: months of hard labour and frustration suddenly seem well worth while after all.

Dave Ablitt and Gilbert Clarke have already appeared in this brief note. To them Sneinton Magazine owes its inception and continued existence. Dave was perhaps the driving spirit in getting the magazine established, and I don’t think anyone else could have achieved it. Since Dave retired from participation in the magazine, Gilbert has performed wonders in editing, writing, illustration and physical setting-up of the periodical. Not only this, he has doggedly drummed up advertising income, cajoled shopkeepers into stocking it, and pestered sluggard writers for their contributions. I cannot imagine how he has managed it all.

I have been indebted, not only to these two, but also to others, like Bill Vincent, whose fine drawings adorned some early articles. (The first dozen or so issues also featured splendid original artwork on the cover, mostly by Rob Dannatt.) As mentioned earlier, friends have been a great help in suggesting potential sources of information, and also in reading articles in draft. In doing so they have saved me from making even more errors than I did. My wife Sue has proof-read more articles than she cares to remember, reproving me when my writing has been unintelligible, and when I have unreasonably assumed in the reader prior knowledge of a subject.

As I write, nobody can tell how much longer the magazine will go on, but it is good to know that Nottingham Local Studies Library in Angel Row keeps a complete file in its reference stock. So, if the vagaries of library policy and the actions of a world seemingly set on selfdestruction allow, future generations who stumble across Sneinton Magazine will be able to read about some of the more recondite episodes in Sneinton’s history. Not only this, they will learn something of what Sneinton was thinking and doing between 1981 and 2006. And perhaps for some time after that.

STEPHEN has made his regular, much valued, unstintingly researched contributions over the full twenty-five years of this magazine’s existence - for which we - and generations to come should be extremely grateful.

He continues to fill with sure touch, what was a considerable gap in the history of Sneinton.

< Previous