< Previous

SNEINTON’S EDWARDIAN TILES:

A threatened legacy

By Stephen Best

WHEN I BEGAN TO PREPARE AN earlier version of this article for Nottingham Civic Society Newsletter, I was intending that it should be something of a celebration of one of Sneinton’s finest, but unsung, assets. As things have turned out, however, this account has become tinged with a sense of anger and almost of despair.

A quarter of a century ago I first became aware of the diversity of colourful ceramic tiles in the front porches of many Sneinton houses, and decided to set about recording them. Consequently I wrote to Hans van Lemmen of Leeds, a leading authority on the subject, asking for advice on how to find out who had manufactured these tiles. Following an exchange of correspondence it was suggested that I submit a very short article about the tiles of Sneinton for Glazed Expressions, the elegantly-titled journal of the Tiles & Architectural Ceramics Society.

This brief piece, accompanied by illustrations of porches in Port Arthur Road and Holborn Avenue, appeared in its Spring 1990 issue, and was thereafter rather forgotten about. My memory was jogged, however, by the appearance in 2005 of the Society’s Tile Gazetteer; a Guide to British Tile and Architectural Ceramics Locations, edited by Lynn Pearson. Several of this book’s finely illustrated pages are devoted to Nottinghamshire, and it was especially good to find a brief reference to Sneinton: 'Just east of the city centre in Sneinton a wide range of porch dado tiling may be found in an area taking in over thirty streets. Here the housing generally dates from between 1900 and 1914, and over 250 different tile designs have been recorded including striking art nouveau flowers.’

The inclusion of Sneinton in a survey of this kind must surely be good news? Perhaps visitors drawn to Nottingham to see the tiles and other ceramic features inside and outside the city’s better-known buildings might in future be tempted to join those who were following the trails of George Green and William Booth, and venture into this interesting, but unfashionable and far-from- glamorous locality? It was, though, rather disappointing to note that no other areas of Nottingham were listed here as featuring decorative tiles on private houses. There must, surely, be further worthwhile examples in and around the city awaiting recording and writing- up. And, as this account will later make clear, recording tiles is most definitely not a project to be put off until a later date.

Here, as a matter of record, is the text of the 1990 article for Glazed Expressions: the title was not chosen by me, but I thought it entirely appropriate at the time.

Worth A Detour: Sneinton

Sneinton (pronounced Snenton) is a district of Nottingham chiefly visited for the birthplace of William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army; and for Green’s Mill, a recently restored windmill associated with the mathematical physicist George Green. It has an active and influential Environmental Society, and it was as a member of this that I began, several years ago, to photograph details of ordinary houses in the neighbourhood.

Many people think of Sneinton as a typically grey inner-city area, and, indeed, I had been familiar with the place for years before I became aware of the wealth of colour in the tiled porches of many of its houses. Over 30 Sneinton streets, almost all built between 1900 and 1914, have examples of these tiles, ranging from plain and subdued designs to some truly lavish displays. It seemed sensible to record these before they disappeared, and I was surprised to find some 250 different designs or combinations of designs. Not all the fortunate possessors of these splendid tiles seem to appreciate them; some are painted over, some chipped out, while a growing number are obscured by intrusive gas and electricity meters.

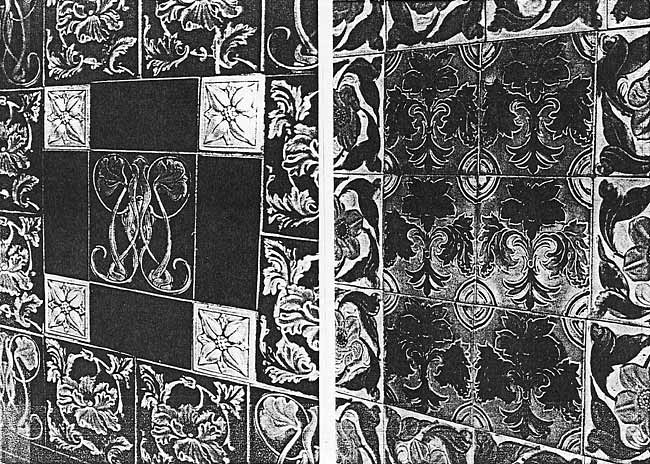

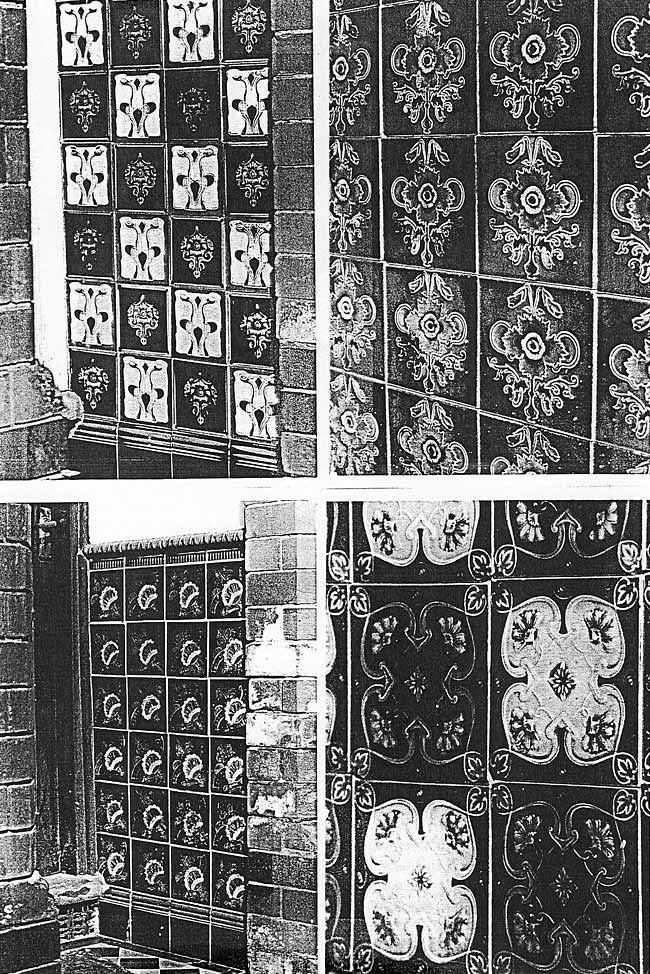

GONE: Porch tiles in Holborn Avenue and Sandringham Road.

GONE: Porch tiles in Holborn Avenue and Sandringham Road.The designs include blackberries, water lilies, and some striking Art Nouveau flowers, reminiscent of stained-glass motifs. Some of the stylised flowers have an 'Aubrey Beardsley feel’ about them, while others take on the appearance of fantastic insect forms. With the exception of a few which are tiled to their full height, the Sneinton porches have a tiled dado only. Builders here seem to have concentrated almost exclusively on porches for external tile display, but I have found just one house whose bays, below the bedroom windows, bear pretty tiles adorned with apples.

A selection from the Sneinton photographs is now in the Local Studies collection of Nottinghamshire County Library. A local display of some of the tile views aroused some interest, with a Sneinton Cub pack embarking on their own tile hunt. Now I hope to identify the manufacturers of the tiles. There seem to be more sources of information than I had realised: to my shame I was, until recently, quite unaware of the existence of the Tiles & Architectural Ceramics Society.

Sneinton’s tiles may, compared with the finest examples, be only an average collection, but they are one of the minor treasures of our area. I enjoyed the labour of photography, despite acquiring the reputation of an eccentric in the neighbourhood, and I hope that residents in other parts of Nottingham will scour their streets for similarly striking examples. I am sure that much remains to be discovered.

Has anything changed since this was written some eighteen years ago? Well, the fact that you are reading this in Sneinton Magazine shows that the Sneinton Environmental Society remains in being, though perhaps not as active as formerly. The Local Studies Library still possesses the photographs, although, following the city's acquisition of unitary authority status, Nottingham’s libraries are now back under the control of Nottingham City Council, rather than Nottinghamshire County Council. My intention to discover the makers of the tiles regrettably came to nothing. It is just one of the numerous projects which over the years were put to one side and never taken up again.

But what of the tiles themselves? How well have they fared over the two decades since this small survey took place? The examples in Sneinton are unprotected by any kind of listing, and their continued survival has always depended on the owners of the individual properties. I had wondered how enlightened these people had proved to be since the 1980s, and it was apparent that the only way to find out was, for the first time in years, to revisit, a few at a time, all the examples photographed.

I possess views of tiled porches in thirty-one streets in the vicinity. Some, like those in Sneinton Hermitage, Colwick Road, Dale Street, and Sneinton Dale, are passed, largely unnoticed, I guess, by many people every day: on foot, or in buses and cars. The location of others - those in Kingsley Road and Ladysmith Street, for example, and the cul-de-sacs lying to the north of the Dale - suggests that only residents and regular visitors are likely to have spotted them. I had always hoped that those who lived in, or owned a Sneinton house whose porch was adorned by these lovely tiles, would realize how privileged they were.

It soon became clear that two kinds of obstacles to the wider enjoyment of the tiles had become comparatively widespread since the 1980s. The reasons for both of these are perfectly understandable, but they inevitably detract from the Sneinton streetscape. First, a dozen or more properties photographed in the eighties have now acquired outer front doors which totally conceal the porches from the passer-by. It is of course hoped that the tiles survive intact behind these, and will remain in good condition, shielded as they now are from the weather. It is unfortunate, though, that so many of the new doors are so ill-matched to the houses they now adorn. And - an incidental grumble - why do so many householders no longer think it necessary to display a house number on or near their front doors? People are quick to complain of the late arrival (or nonarrival) of mail, but the hapless postman does at least deserve the assistance of a clearly visible house number at every address.

One of these new extra outer doors is now fitted to a house in Sneinton Dale whose porch was among the very rare examples in the area of floor to ceiling tiling. This one is now part of a dental practice, as is its next-door neighbour, which had a similarly tiled porch. In the latter, however, the porch remains visible from the street, but the tiles, if they still exist in situ, are hidden behind panelling on the side walls of the porch.

A second recent development has been the fitting of a metal grille across the porches of a few houses, which, while undeniably an invaluable security feature, lessens the visual impact of the tiles. A house in Lyndhurst Road has been cruelly dealt with in a different way, one side of the porch tiling having being removed to make way for a meter box.

Even though any tile enthusiast would be disappointed by these developments, it had thus far been possible to console oneself with the thought, that, after all, the relevant tiles were probably safely hidden away, and might at some future time be again revealed to the general gaze. This comfortable state of mind could not, however, survive the realization of another category of tile losses. One’s reaction on first learning about these was sadness, quickly overtaken by fury. Something happened a few years ago which appears to have been nothing less than the looting of one of Sneinton’s richest collection of tiles, in Port Arthur Road. In this street, ten or eleven houses whose porches were photographed in the 1980s - all in a row on the odd-numbered side of the road - have been stripped altogether of their tiles, while another now retains just part of the bottom courses, showing where the tiles were hacked out. One porch whose tiles have been removed is left unplastered, with rough brickwork showing, while others have been indifferently painted or plastered.

Lost to Sneinton: Four Tiled Porches in Port Arthur Road

Lost to Sneinton: Four Tiled Porches in Port Arthur RoadWho could have inflicted this treatment on the houses, and why? At first I wondered whether any element of the Sneinton community might have found them objectionable, but could find nothing in any of the designs which might have given offence to anyone, of whatever culture. There was no apparent structural reason for the removal of these tiles, and nobody in their right mind could imagine that the houses would in any way be enhanced by their elimination. Do bear in mind that these were arguably the best tiles that Sneinton possessed. There remained the possibility that someone in, or on the fringes of the architectural reclamation business had noticed these houses, and felt that their porch tiles would find a ready sale.

This, it seems, is just what did what happen. John Hose, who at the time lived across the road from the scene of this devastation, remembers the very messy state in which the denuded porches had been left. Not only this, he recalls actually hearing an attempt to chisel out tiles after dark from a house in Sneinton Dale, just around the corner from Port Arthur Road: on this latter occasion, fortunately, the perpetrators were caught. He himself was the victim of a theft of a fireplace from a house in Sandringham Road that he had just vacated, but which still contained a number of his possessions. The police, in discussing this episode of vandalism with him, pointed out that people who were responsible for this kind of architectural stripping were in business only because they knew they had customers waiting.

To sum up, then, we find Sneinton, a neighbourhood which badly needs to retain all its better features, denuded to supply the wants of people in more favoured locations, with money to spend, and the desire to do up their own properties.

It must be emphasized that, in all probability, only a very few people were involved in this ransacking of our streets. An area like Sneinton, however, just cannot afford to be pillaged of its finer points. A walk around the district reveals a locality with a large and multi-cultural population, some of whom, understandably, have little knowledge of, or feeling for the history of the place. They include an increasing number of full-time university students, who are inevitably transient dwellers in Sneinton, and whose houses tend to be unoccupied and apparently unloved for a considerable part of the year.

Whoever removes the ceramic tiles from houses in Sneinton and similar inner-city suburbs is stripping these areas of one of their irreplaceable highlights. In the first decade of the twentieth century, new building in Sneinton extended east of the parish church, and along the principal streets: the Dale, Colwick Road, and Sneinton Boulevard. In these streets, and those leading off them, the style of the houses was a sort of statement. Here was a self- respecting artisan and lower middle-class suburb, and many of its homes bore the outward signs of this aspiration to something better than the mid-Victorian dwellings off Sneinton Road. These Edwardian houses featured bay-windows, house-names, front areas behind stone walls, and tiled porches with carved heads flanking the entrances. The loss of any of these tiles inflicts a real wound on the locality, and robs Sneinton of much-needed colour.

Although Port Arthur Road may have borne some of the worst of these losses, other streets have suffered in the same way. Just across Sneinton Dale, in Holborn Avenue, three adjacent houses have suffered the total or partial removal of their tiles, which, with the Port Arthur Road ones, were among the most spectacular in the neighbourhood. And nearby, three houses in Sandringham Road have been similarly defaced.

Further isolated examples of the same treatment can be found in, among other places, St Stephen’s Road, Sneinton Hermitage, Colwick Road, Victoria Avenue, Lees Hill Street, Trent Lane and Lyndhurst Road. One small consolation can be found in the act of a family living in the last-named street who were robbed of half the tiles in their porch while sleeping, but who afterwards, at considerable expense, had copies of the missing tiles made and fixed. If only this kind of pride in one’s surroundings were more widespread.

It is, I suppose, possible that in a few instances tiles may have been misguidedly eradicated as part of the modernisation and ‘improvement’ of property. Of all the examples found, however, only two or three houses suggest that removal of the porch tiles has been followed by anything approaching an attempt at creating a proper redecoration of the porch.

My own interest in tiles began some 27 years ago, when my wife and I bought a set of four at an antiques market in Lincoln. We believed that these had come from the bedroom fireplace of a demolished Victorian house, but I am now beginning to feel uneasy about their provenance. And after a decade and a half I am beset by pangs of conscience for having sent photographs of tiles in Port Arthur Road and Holborn Avenue to Glazed Expressions. Could the wrong people have seen these in print ?

As many readers of Sneinton Magazine will be well aware, two prominent local champions of Sneinton conservation have in the last few years moved away from homes in the centre of Sneinton to other parts of Nottingham, and their sharp eyes are greatly missed locally. Those enthusiasts who remain in the neighbourhood, and care about its built environment, now clearly need to be doubly vigilant. To be blunt, they need eyes in their backsides. Since the middle of the 1980s more than one eighth of the tiles in Sneinton porches photographed by me have been lost, for whatever reason. A further significant number are no longer visible from the street, and may or may not still exist. Although it is highly unlikely that the loss of any of the tiles could have been foreseen or averted, such depredations should never be allowed to occur without, at the very least, some vigorous public expression of protest.

At this time of writing, February 2007, Sneinton may still be worth a detour for the tilelover, but its charms are undeniably diminished for the reasons already indicated. If anyone would like to see all of Sneinton’s most beautiful ceramic tiles, I have a couple of albums of photographs that I will be glad to show them. I would also be happy to accompany anyone interested in a stroll round the area, to enjoy the best of those that remain. In spite of the vandalism that has occurred, there are still some beautiful tiles to appreciate here. From now on, though, I won’t state in print where I think the best surviving Sneinton tiles are to be found. Nor will I in future blame anybody who has an iron grille gate fixed to protect the attractive tiles in their front porch. And if anyone offers a plausible reason why your house would be better off without the tiles in your porch, please send them packing with a flea in their ear.

Returning to the Tile Gazetteer, whose publication prompted this article, it is a pleasure to be able to recommend a book so wholeheartedly. Its introduction consists of a series of authoritative short essays on the various periods of decorative ceramics in architecture, and discusses their application in civic buildings, churches, hospitals, factories, breweries, and so on.

The gazetteer section covers England, Scotland and Wales. It is finely illustrated, in monochrome and colour, and at the end of each county or district section is a useful bibliography. Anyone walking around the centre of Nottingham with the book in hand is likely to find something new, or to be reminded of something half-forgotten. Even those who have lived in the city all their lives will be surprised by what they have hitherto missed. And, as a reassurance, if one be needed, that there are things to praise in the city’s recent architecture, one of the illustrations shows the 2001 tile mural on John Lewis’s Milton Street frontage.

Gazeteer notes: Final paragraph...

The appendices include a valuable biographical directory of tile designers and manufacturers, a glossary of relevant terms, and a more extended bibliography. The book ends with two indexes: of artists, etc., and of places. For 512 copiously illustrated pages, the price is very reasonable.

Lynn Pearson (editor), Tile Gazetteer: a Guide to British Tile and Architectural Ceramics Locations. Richard Dennis, 2005. £25.00. 0 903685 97 3

< Previous