< Previous

NEAT and PICTURESQUE:

St Luke’s Schools and their donor

By Stephen Best

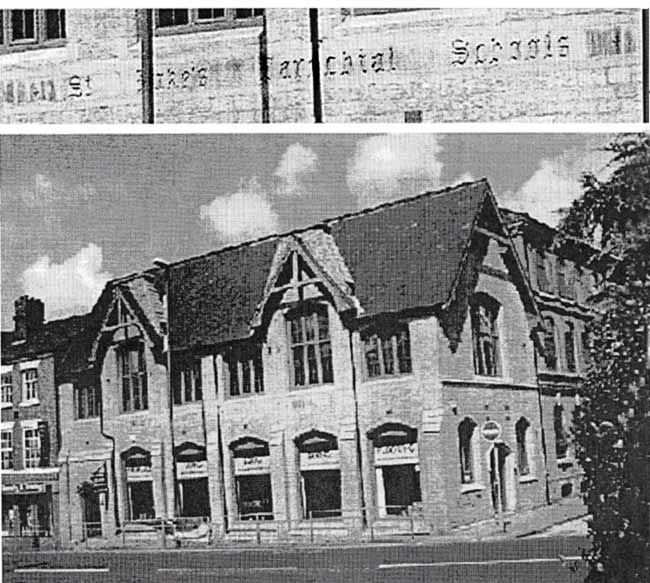

The Carlton Road frontage and name panel today (July 2007)

The Carlton Road frontage and name panel today (July 2007)AN ATTRACTIVE AND DISTINCTIVE little building on the edge of Sneinton has recently been spruced up, and looks all the better for it. Standing in Carlton Road opposite the foot of Walker Street, it was until quite recently the home of the Tennant Rubber Company. Regular readers of Sneinton Magazine may from time to time have read some explanation of its original identity. Now, though, following the conversion of its ground floor to accommodate a furnishing store, the previous occupant’s old fascia has been removed, and all passers-by can see for themselves what the building used to be. The alterations have revealed a long-hidden carved inscription in Gothic lettering: + St Luke's Parochial Schools +

Very early in the 1860s, part of the very large town centre parish of St Mary’s was designated the district of St Luke, and to serve the rapidly growing neighbourhood a church was built at the comer of Carlton Road and Woodborough Street (later renamed St Luke’s Street) The site was close to new streets which were being built on the Clayfield, made available for building by the 1845 Inclosure Act. The church district was, however, far more extensive than this. In its earliest period it stretched from St Ann’s Well Road to Carlton Road, taking in all the houses between Bath Street and Alfred Street. From Sneinton Market it ran south as far as the canal, and included the very poor area between Manvers Street and Carter Gate. At its southern end it took in the Poplar Street and Island Street area lying off London Road.

The foundation stone of St Luke’s church was laid on 2 July 1861 by the lace manufacturer Thomas Adams, who, according to the Nottingham Review, delivered an apposite address to the assemblage present. Paid for largely by public subscription, the building was designed by Robert Jalland of Castle Gate. In the Early English style, it was expected to hold 900 people. Construction was initially in the hands of Thomas Garland, of St Ann’s Well Road. He, however, had the misfortune to be declared bankrupt, and work on the church was held up until the building job was taken over by C.C. and A. Dennett of Station Street. A further misfortune occurred in 1862 when the uncompleted church was severely damaged in a gale.

The building was eventually consecrated on 24 February 1863 by the Bishop of Lincoln, and received few plaudits from the local press. The Nottingham Review considered that : More attention has been paid to obtain accommodation than to architectural beauty. The Nottingham Journal however, pointed out that that the new church was in a populous and rapidly growing neighbourhood, and so would be of great service. Though not finding much to praise in the church's architectural features, the Journal did recognize that Jalland had succeeded in accommodating the largest possible number of worshippers at moderate cost.

In its report of the consecration of St Luke’s, the paper remarked that: It is proposed, we understand to erect new schools as soon as the funds will permit - a result which all the friends of the undertaking will hail with satisfaction.. It will soon be made clear how quickly this hope was to become a reality.

One year after the opening of St Luke‘s, a much grander church was nearing completion in a rather more fortunate area of Nottingham close to the Arboretum. All Saints church in Raleigh Street, together with its vicarage, verger's house and parish rooms, was almost ready for use. All this was the result of the munificence of William Windley, a Nottingham silk throwster, who had spent some £10,000 in the provision of these buildings, engaging for the commission the town’s most notable architect, Thomas Chambers Hine.

Windley & Barwick’s factory was a near neighbour of St Luke’s, standing as it did in Robin Hood Street, a two-minute walk from St Luke’s church. William Windley will reappear later in this short account, but a different benefactor now takes centre stage, as the provider of a school for the St Luke’s district.

The Nottingham Journal of 29 March 1864 clearly believed that Windley’s philanthropic example had inspired another Nottingham businessman: Already the princely and single- hearted liberality of the founder of All Saints' Church has borne fruit, and the populous district of St Luke’s is to be blessed with parochial schools, erected at the sole cost of Mr J.H Lee, head of the firm of Lee and Gee, hosiery manufacturers, Roden Street, their factory and warehouse being within the district and close by St Luke's Church.

Although James Holwell Lee is the central character of this short account, his name does not figure prominently in any history of nineteenth century Nottingham, and no portrait of him is known to this writer. Never serving on the Borough Council, Lee was one of the town’s Victorian benefactors who was rarely in the limelight. In 1864 he was, according to the directory, resident in Regent Street, then just about a decade old, and one of the town’s most fashionable addresses. Three years earlier the census had listed him at Wellington House, Wellington Circus. His was a small household, consisting of himself, his second wife, and a daughter by his first marriage. Mr Lee, then 42, gave his occupation as hosier, and employed a living-in cook and a housemaid.

In 1867 he bought the comfortable rural house named Lenton Fields, in Beeston Lane: this house was later annexe to a Nottingham University hall of residence. The 1871 census shows Lee at the age of 52, terming himself Magistrate and landowner: cotton spinner and hosier employing about 100 people. At this time Lee’s family comprised his wife, and six children from his two marriages, ranging from five to 27 years old. Two sons from his first marriage were described as a hosier and a cotton spinner. Three female servants lived in, and Lee also employed a gardener who resided at the lodge.

There followed a period during which Lenton Fields was let, with the Lee family living at Newcastle Drive, in The Park. He appeared under this address in the 1881 census, by now giving his occupation as J.P., Retired hosier. A nineteen-year-old son was articled clerk to a solicitor, and the Lees enjoyed the domestic assistance of a resident cook, housemaid and parlour maid. Mr Lee was, however, back at Lenton Fields when his death occurred in his seventy-second year, on 3 March 1890. Two days afterwards the Evening Post remarked that he ...was highly esteemed for his integrity of character and business aptitude. Though he never took a prominent public position Mr Lee was identified with many philanthropic institutions, and in 1865 was placed upon the commission of the peace for the borough of Nottingham. He was an earnest supporter of the Conservative cause, and a staunch Churchman.

Three days later the same newspaper briefly reported Lee’s funeral, which appears to have been remarkable for its modesty. The Evening Post related that: Devoid of either pomp or splendour, the remains of the late Mr James Holwell Lee, J.P., were interred in the Nottingham Church Cemetery to-day at noon. Four coaches and a private carriage had followed the hearse from Lenton Fields to St Andrew’s church. On the other side of Mansfield Road, a few people awaited the procession at the cemetery gates to accompany it the graveside. In his will Lee left personal estate amounting to over £33,000, an enormous sum which at that time would have paid almost exactly half the cost of the new Nottingham Guildhall in Burton Street.

We have, however, gone far ahead of events, and must return to 1864, when J.H. Lee was in his mid-forties, and not yet a magistrate. His factory, like that of Windley, was only a stone’s throw from St Luke’s church, just around the comer in Alfred Street, at its junction with Roden Street. As will soon become apparent, Lee was deeply concerned for the welfare of the inhabitants of this neighbourhood, some of whom would have been among his workforce.

The site chosen for the new schools could not have been closer to the parent church, being only ten yards from it, at the opposite comer of St Luke’s Street (the new name for Woodborough Street.) Although the laying of the foundation stone on Easter Monday 1864 might today seem an event of limited interest, the Nottingham press afforded a considerable amount of space to it.

The Nottingham Review in particular paid close attention displayed to the design of the new schools, and described very well the exterior of the building which survives today. Pointing out that the school would harmonise with the architecture of the church itself, and of a projected parsonage in Handel Street, the account continued: Owing to the smallness of the sum allowed to be expended, the elevations will necessarily be devoid of much architectural ornament, but, from a description of the plans, it is justifiable to say that the appearance of the building will be neat and picturesque. The cost will be about £700, and we are happy to state that this sum has been contributed by the liberality of J.H. Lee, Esq., who has evinced an instance of munificence worthy of all commendation.

Turning to the internal arrangements of the school, it was stated that the ground floor would contain a girls’ school 60 ft. by 20 ft., and a classroom 14 ft by 12 ft. Upstairs, and reached by a stone staircase, was to be a boys’ school of similar dimensions and layout. The rooms are to be lofty, well lighted, thoroughly ventilated, and warmed with open fireplaces. The roof is to be open-timbered, showing the spars and principals.

The girls’ school entrance was to be in St Luke’s Street, while the boys would come into school through a door in the Carlton Road frontage. The exterior will be faced with Bulwell stone, having Hollington stone dressings to the doors, windows, and buttresses. Two gablets on the side elevation facing Carlton Road will have the chimneys continued with them so as to preserve unity of effect, and form a pleasing architectural feature. The architect is Mr Fredk. Bakewell, and the contractor Mr Richard Willimott, Shakespeare Street.

In Frederick Bakewell of Thurland Street, St Luke’s School had found a prominent local architect, whose impressive School of Art was in 1864 in course of erection at the foot of Waverley Street. The firm of Bakewell & Bromley, was, a decade later, to make a much bigger impact on the Sneinton neighbourhood with the huge Victoria Buildings block in Bath Street. In the latter case, however, Frederick Bakewell’s younger partner, Albert Nelson Bromley, was responsible for the design.

After a service in St Luke’s church, attended by a tolerably large congregation, the dignitaries, guests and onlookers adjourned to the site of the schools. That is, they walked across the road. Conducting the proceedings, the Rev. Henry Daniel, perpetual curate of St Luke’s, was accompanied by five other members of the clergy. After the singing of Psalm 108, the foundation stone was lowered into place, and Mr Lee declared it well and truly laid. Under the stone was placed a bottle, containing Nottingham newspapers of the day, and a scroll stating that the stone had been laid at 3 p.m. in the presence of, among others, William Windley and William Gee, the latter being James Holwell Lee’s business partner, and his near neighbour in Regent Street. The cost of Willimott’s building contract for the schools, £615.15s., was also recorded.

After the stone-laying, Mr Lee mounted a makeshift platform, to tell his hearers that, as the occasion had been announced as a public one, he supposed that a few words would be expected from him. His remarks are interesting as coming from an enlightened businessman and employer of the Victorian period. It is salutary to remember that in 1864 a young child was not guaranteed an elementary education in England; that would come with Forster’s Act of 1870. Even then, such an education was neither compulsory nor free. A.J. Mundella’s Act of 1880 would introduce compulsion, giving universal education for small children, and in 1891 this elementary education was made free.

Lee began by saying that it was always pleasing to be engaged in any useful works, especially when the object was one of a public nature, and of deep interest to his fellow- creatures. The new St Luke’s Parochial Schools would, he stated, be capable of accommodating between three and four hundred boys and girls, and would also provide a meeting-place for the St Luke’s Sunday School, which had nowhere in which to assemble other than the church itself. To show the great necessity of such a building, I may mention that there does not now exist in this parish in connection with the church, any place where public instruction is given. When I further state that the parish of St Luke contains a population of about 10,000 souls, almost entirely of the working classes, I think I have said enough to enlist your active sympathy in the success of this undertaking. (Hear, hear.)

He acknowledged that differences of opinion existed as to the best mode of giving instruction to the children of our working population, but declared that as this was a Church of England school, the Bible would be the foundation of their teaching.

Mr Lee understood the financial problems encountered by many families, and realised that the education of their children might make matters more difficult. Nonetheless he pleaded with parents to let their children come to school: It is said that the condition of succeeding generations depends upon the actions of the present. If this be true I cannot do better on the present occasion than to make an appeal to the working-classes of this neighbourhood to give their children the benefit of such an education as St Luke’s schools may afford. I know it may call for self-denial on the part of some who need the earnings of their children to assist in providing the necessaries of life.

He touched next on an event which had a disastrous effect on British trade: There are also many, especially in this immediate neighbourhood, who have been depending upon the state of the cotton trade for their earnings, who during the last three years have suffered the most extreme privations. From personal experience I can bear testimony to the admirable manner in which they have endured these privations. Their fortitude and patience have been most admirable. James Holwell Lee was referring to the effects of the ‘Cotton Famine’ of 1861-65, when the American Civil War, and the resulting blockade of the Southern States, cut off the supply of American cotton to Britain. As some 85% of all the cotton processed in British mills came from America, this had devastating consequences for the trade.

While recognising the burden under which poor families struggled, Lee’s belief in educating the young remained undiminished: I think, however, we have at length passed through the worst of our trials, and if that is so I hope the parents will allow their children to come here and receive that early training before they are sent to work which will enable them to carry on the great work of self- education in after life. (Hear, hear.) Here is an influence at all times to refine the mind, and a power capable of enhancing the happiness of life, in a greater degree than any other human agency. Most of you know how much is lost by neglecting all these opportunities, how often in our intercourse with the world we meet with persons of the brightest intellect whose undeveloped powers forcibly remind us of the beautiful lines of the poet.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear;

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Yet, in this free country, instances abound in which men have risen from the humblest walks of life to adorn the highest offices in the state, proving what may be done by diligent perseverance. Surely, if such results are to be found, it is our duty as well as our interest to avail ourselves of every opportunity which occurs of improving ourselves.

In concluding these quite impassioned remarks, J.H. Lee expressed his appreciation of the way the incumbent of St Luke’s, the Rev. Henry Daniel, had carried out his pastoral duties in the year or so that he had been at the church. Mr Daniel, he said, had won the hearty good wishes of all parishioners, and it was to be hoped that the new schools would help him advance his work in the parish. Lee also alluded to his belief that the completion of the schools would give very pleasant satisfaction to one who was very present that day, but was about to remove to another sphere of labour.

The person thus alluded to was the septuagenarian Canon Joshua William Brooks, vicar of St Mary’s church, Nottingham, since 1844, who was about to leave his crowded town parish for the much quieter one of Great Ponton, near Grantham. The canon was then invited by Mr Daniel to say a few words, and accordingly did so. The assembled onlookers may well have been glad when he had finished: this was late March, remember, and the ceremony, beginning at 3 p.m., was taking place in the open air.

Adherents of St Luke’s with energy to spare were able to attend a very pleasant social gathering...in the evening at St Mary’s Girls’ School-room, Barker Gate, 200 of the congregation and their friends sitting down to a capital tea, served by the ubiquitous Mr Bentley, [confectioner] of Charlotte Street. Anthems having been sung by the augmented choir of St Luke’s, Mr Daniel gave an address on some features of his ministry. Few of his hearers could have imagined that this vigorous young parson, only 31 years old, would be dead in little over a year.

In 1865 Daniel was taking part in a parish outing, when it was noticed that he was far from well. Within a few days he died of typhoid fever: the result, it was believed, of incessant work in poor and unhealthy districts of Nottingham. So highly was he regarded by his parishioners that his funeral procession, so contemporary reports stated, stretched unbroken from St Luke’s church in Carlton Road to the graveside in the St Mary’s cemetery in Bath Street. The Rev. Henry Daniel’s memorial can still be seen here; it is one of the very few to have remained in place after the conversion of the burial ground into a rest garden and urban amenity.

In the event the internal layout of the schools described by the Nottingham Review did not materialize: the older boys occupied the ground floor, with the girls and infants upstairs. Space was soon at a premium, and yet again St Luke’s was indebted to a local businessman for providing classrooms. This was the William Windley already mentioned, whose industrial premises are still a local landmark. Most Sneinton people know the former Bancroft’s factory, at the corner of Roden Street and Robin Hood Street, with its unusual wind clock, and impressive inspection floor. This building, lately converted into apartments, was built in 1869 for Windley’s silk manufacturing business.

Having already benefited Nottingham with All Saints’ church and its associated buildings, Windley placed the town further in his debt by providing a new boys’ school for St Luke’s, at the junction of Salford Street (which ran from Robin Hood Street to Alfred Street,) and Liverpool Street, leading off Handel Street. With the boys gone from St Luke’s Street, the girls and infants were able to enjoy the use of all the 1864 building.

William Windley was to have another strong connection with Sneinton. His son, the Rev. Thomas William Windley, was vicar of Sneinton for four years in the 1880s, following the hugely influential Canon Vernon Hutton. Windley’s incumbency here was less than successful, and it was suggested that he had been exhausted by an eight-year stint as a missionary in Burma.

The St Luke’s parochial schools were to have a life of less than forty years. Changes in educational theory and practice, and a very proper requirement for a better environment for children to learn in, would soon find the buildings wanting. There was, however, much to feel proud about. In September 1891 the St Luke’s parish magazine proclaimed: Our Infant School, Carlton Road, we have not the slightest hesitation in saying, can compete with any school. The Girls’ School was very successful in the last examination, and earned the 'Highest Possible’ grant in all subjects. About the Boys ’ School, Liverpool Street, we need say very little. It has a good name among parents, and the yearly reports from H.M. Inspector show that it maintains its reputation. The boys receive a sound commercial education, and many of our scholars have turned out successful business men. ’

James Holwell Lee and William Windley would have been proud of such affirmation of the success of the schools they had made possible, but there were undeniably problems, and by 1894 the administration of St Luke’s Schools had been taken over by the Nottingham School Board.

The School Board managers’ minutes for that year gave some idea of the state of affairs at St Luke’s. The salary bill for the seven members of the combined teaching staff of the three school departments amounted to just over £35 for the month of April. Mr Wilson, head master of the Boys’ School, received £10.8.4d, while the head mistresses of the Girls’ and Infants’ Schools were each paid £6.13.4d. At the end of May the managers noted the plight of the junior pupil teachers at the school: so serious was the shortage of staff that they could not be spared to attend their Pupil Teacher classes. Not surprisingly, perhaps, it was noted that there were no certificated assistants at St Luke’s Boys’ School. Extra staff were indeed appointed later in the year, but the managers felt unable to grant a request that the schools be allowed a piano.

Although the Board was sympathetic, the writing was unmistakeably on the wall. Their report for 1895 observed: We are sorry that two of the old Voluntary Schools of the town - St Luke’s School, with 450 children, and the Arkwright St. Wesleyan School, with 644 - have, under the severe pressure of the present time, found it impossible to maintain themselves upon the old footing. In this way alone 1,094 children have passed to the care of the Board.

For the next few years, the School Board annual reports reported what the inspectors had thought of St Luke’s Schools. Sometimes the comments were a little bland: in 1895-6: Some boys were not so tidy as they could be and should be. No great shock there. Nor could it have surprised many to read to read of the infants in the following year: They are very kindly treated.

Altogether more serious for the long-term future of the school buildings was the comment that the class room in the infants' school is habitually used for a larger number of scholars than for which it is passed by the Department. This problem was re-emphasized in 1897-8 when the inspectors observed that: Considering their confined accommodation they are in excellent order...The attendance should be reduced or the accommodation increased.

As if this lack of classroom space were not a sufficient handicap, another very serious drawback was the lack of any playground for the children. The extension of school premises in Bath Street and the building of new ones in Carlton Road meant that time had run out for the schools given to the local community by the local businessmen-benefactors, Messrs Lee and Windley.

The School Board report for 1900-01 gave St Luke’s Schools a well-deserved last line on which to bow out. Boys’ School - This school is instructed in an earnest and successful manner. The boys are under an excellent influence. Girls’ School - The work was highly satisfactory, and the order very good. Infants’ School - The work is very good, and the tone and order are excellent.

The teachers could do nothing about the inadequacy of the buildings, and were entitled to feel they had done their very best in outdated premises. It was believed in the parish that the forthcoming end of the schools had saddened the last months of the long-serving vicar of St Luke’s. This was the Rev. Edward Rodgers, who had come to the parish in 1865, following the untimely death of the Rev. Henry Daniel. Mr Rodgers died in July 1900, aged eighty, having been longer in his benefice than any other Nottingham clergyman of his time.

Not only did the schools close down, but the depopulation of the surrounding area as a result of slum clearance meant that in time St Luke’s church itself became redundant. In 1921 it was reported that the parish, whose boundaries had been altered more than once, would probably be united with St Philip’s in Pennyfoot Street, into which parish part of St Luke’s district had been transferred when St Philip’s was opened in the late 1870s. The added news that of the 3,763 people who lived in St Luke’s parish, only 25 were on the church electoral roll, can only have confirmed the inevitability of closure. On 27 November 1924 its final service was held. (The fourth-from-last couple to be married here, on Sunday 10 August, were the present writer’s uncle George Best and his godmother Mabel Chambers.)

The church was demolished late in 1925, and its site occupied by the Nottingham City Mission, opened in May 1927. Demolition was carried out by a man called Frank Stell, who had purchased the site. Before the Great War Stell had bought the old vicarage in Handel Street, replacing it in 1913 with ‘Vicarage Works,’ a building with Arts and Crafts touches, in which he installed his own textile making-up firm together with other businesses in the embroidery, lace curtain and blouse trades.

Frank Stell is one of those figures on the periphery of our local history who invites further research. On his death in August 1945 the Nottingham papers described him as a retired builder, formerly successful in the lace and making-up industries. When younger he was associated with the Methodist Church, later becoming a Christian Scientist. Throughout his life he had been a supporter of many churches and missions. Interestingly, from the viewpoint of Sneinton history, Stell had been prominent in several housing developments, in particular the Bakersfields Estate at the top of Sneinton Dale; he died in this neighbourhood at his home, 138 Oakdale Road.

Stell’s sympathy and support for missions clearly found expression in the new City Mission. Its architect, A.J. Thraves, was also the designer of, among other buildings, the Palais de Danse in Lower Parliament Street and the Dale Cinema in Sneinton Dale. The Congregation of Yahweh now meet in these premises, and also occupy what was earlier a little parade of shops in the mission’s Carlton Road frontage.

The original St Luke’s Schools on the opposite comer saw a variety of uses in the twentieth century. Many local people will remember it as part of the P.D.S.A. complex, and for several decades thereafter it became the Tennant Rubber Company. Recently the building was taken over by Lounge Furnishings, who, it is hoped, will continue to look after it as they are doing now.

It is worth a small detour to enjoy a look at what is one of the jolliest small buildings in the Sneinton area. The stonework is still in fair condition, and its ecclesiastical connections easy to detect, with its pointed Gothicky windows and doorways. As stated at the outset of this article the building’s original purpose can plainly be seen in the inscription ‘St Luke’s Parochial Schools’ on a long strip of stone. The window glazing has unfortunately had to be renewed, but the arched spaces above the upstairs windows still feature ceramic tiles in red and black lozenge patterns. The timber bargeboards on the St Luke’s Street gable end have been made less elaborate than they were by the removal of the central vertical member and the arched pieces at the sides. On the Carlton Road frontage the two smaller ‘gablets,’ as the 1864 newspaper called them, retain their bargeboards, though the finials have been cut down. The chimneys which formerly rose above these gables were lost some time between the mid-1960s and 1980s, the stacks now ending in stone copings just above the bargeboards. The two entrances both have pointed arches, with stone mouldings, and label stops bearing carved foliage.

The later St Luke’s Boys’ School building at the corner of Salford Street and Liverpool Street was in use latterly as a Gospel Hall. It was pulled down during the St Ann’s redevelopment clearances, in which Salford Street was completely removed from the map.

The small area bounded by Bath Street, Handel Street and Carlton Road retains a character all of its own. It seems not quite in Sneinton, nor yet quite out of it. Like many neighbourhoods on the edge of the inner city, it is traversed every day through by people in a hurry, few of whom, one suspects, ever look very closely at it. There are, though, several buildings here worth more than a passing glance.

We are, I think, fortunate to have the original 1864 St Luke’s School building still standing in Carlton Road. It owes its survival to its convenient location and interior layout, which have enabled it to be used for a variety of purposes unimagined by its donor. Its last old pupil must now be long dead, but it is good that Sneinton retains a tangible memory of a humble, hard-working parish church and its schools. James Holwell Lee may not be a household name, but he does deserve something much better than the obscurity into which his name has slipped.

ENVOI

The old St Luke’s Parochial Schools are seen here facing the bottom end of Walker Street, from which location which George Roberts took the accompanying photograph sometime in 1958, on behalf of Nottingham Local Studies Library. The school building has not greatly altered since that date, apart from the loss of its prominent, and it must be said, rather curious chimneys, which here spring from the gables on the Carlton Road frontage.

By 1958 modem council housing has already transformed Walker Street from its old self, but a reminder of what it formerly looked like is provided by the tall terrace houses in West Street, which here have only a very short time left before they are demolished. They exemplify the character of the district of New Sneinton, created in the first half of the nineteenth century. West Walk and Morley Court now occupy the site of the vacant land and West Street.

Adjacent to the old school is a fine Victorian factory building in St Luke’s Street, two years younger than the school. Now (2007) known as Longden Mill, the building, which turns the comer into Longden Street, bears the date 1866. Following conversion, it is currently to let. The industrial character of the neighbourhood is further strengthened by the factory’s tall chimney, whose stump remains today next door to the back entrance of the Earl Howe pub. It is probable that nobody took much notice of this in 1958: half a century ago factory chimneys were commonplace in Nottingham. Now hardly any remain, and this fine example, with superb decorative brickwork at the top, is just a memory.

Immediately to the right of the factory chimney can be seen the top storey of Victoria Buildings in Bath Street, and, a little to the left of the lamp post, the very top of the Victoria Baths clock tower: the familiar ‘Bath Clock’. One very new addition to the Nottingham skyline appears faintly above the roofs in West Street. This is the new building of the Nottingham & District Technical College in Burton Street, opened in May 1958 by Princess Alexandra, and now the Newton Building of Nottingham Trent University. This skyline is now all but blotted out by the very tall buildings which have been inflicted upon the eastern edge of the city centre, but in 2007 it is still possible to see the top of Victoria Buildings from halfway up Walker Street.

The photograph has a strange, almost dreamlike quality about it, which I can only put down to the total absence of humans and the almost complete lack of motor vehicles. I think that this photograph, like many of George Roberts’s most atmospheric views, was secured on a Sunday morning. A solitary Standard Vanguard, already, perhaps, rather passé in 1958, reminds us that we are in the motor age. There are trolleybus wires in Carlton Road, but the camera cannot pick them out. And two designs of street lamp standards can be seen here; both of them far better suited to their surroundings that many of the concrete and metal monstrosities which nowadays disfigure our streets. Happily for Walker Street, it can in 2007 still boast some lamp posts like the one in the foreground.

< Previous