< Previous

SNEINTON’S OWN PORT:

A glimpse from the Thirties

By Stephen Best

IT IS SOMETIMES FORGOTTEN nowadays that Sneinton used to feature on the map of England’s inland waterway transport network, and a few pages in the Nottingham Official Handbook issued in 1935 provide a reminder of this aspect of the locality‘s industrial past.

The handbook includes a map showing Nottingham’s central position in a river and canal system embracing London, Gloucester, Liverpool Manchester, Sheffield, Gainsborough, Boston, and Hull. In the mid- 1950s Hull ranked third in tonnage of English ports, and a regular daily service existed between the Humber and the Trentside communities of Newark and Nottingham.

Before the Great War the Trent Navigation Co. had undertaken works below Newark to facilitate the passage of freight cargoes, and in 1915 The Nottingham Corporation (Trent Navigation Transfer) Act was passed. This meant that from 1917, that part of the Trent Navigation upstream from Newark to Nottingham could be transferred to Nottingham Corporation, giving the Corporation toll rights over this stretch of river.

The Corporation also acquired the rights to build new locks, and to put up warehouses and other structures necessary for the navigation and its associated trade. Following the end of the war Nottingham Corporation exercised its powers under the Act, and began a busy programme of building locks and deepening the river for the passage of larger craft. By 1931 over £400,000 had been spent on these works.

Of interest to Sneinton is what went ahead at the Nottingham end of this section of river. All is described in the handbook. At the end of Trent Lane a miniature inland port took shape.

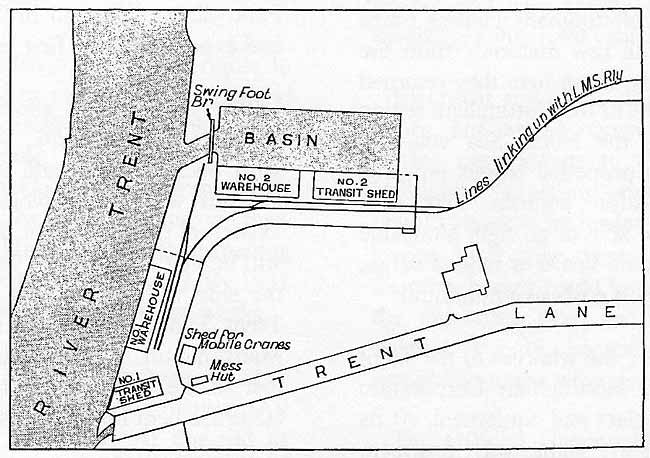

Just upstream from the end of Trent Lane Transit Shed no. 1 was finished in 1928. This was followed within a few years by two warehouses and Transit Shed no. 2. One warehouse fronted the river, while just to the west of it a dock basin was dug out, reached by a narrow entrance from the river which was crossed by a swing bridge.

Warehouse no. 2 and Transit Shed no. 2 stood on the east side of this basin. Sidings from the LMS Railway were included in the plan, and it was anticipated that 'an arterial road in the north’ would greatly improve the approaches to the depot. This was Daleside Road, which was not to deserve its description of ‘arterial’ for several decades afterwards.

The two warehouses were of reinforced concrete, and the handbook asserted that they were unsurpassed by any in the country. Each had nine floors, 170 feet long by 50 feet wide, with a total floor area of 76,500 square feet. To achieve complete freedom from dust, the ground floors of the warehouses were of specially treated concrete, while the other floors were of wood, laid on reinforced concrete.

The two transit sheds afforded another 13,000 square feet of space. All the equipment for the handling of cargo was of the latest design. Specially ordered transporters, hoists, and stackers were electrically driven, and from the upper floors of the warehouses spiral sack shoots and case shoots enabled goods to be discharged into road vehicles or barges.

Electrical light was supplied throughout the depot, and ample concrete roadways allowed lorries easy access to the land side of the buildings. Travelling cranes were available to enable goods to be loaded direct from barges to lorries, and vice versa. At any one time, fourteen barges could be accommodated below the unloading gear, and there was space for another twenty barges to unload cargoes straight on to the wharves.

The Official Handbook produced figures to show that the annual tonnage carried on the Trent had increased more than eight-fold since Nottingham Corporation had assumed responsibility for this section of the Trent Navigation. From an average of just over 29,000 tons between 1913 and 1926, a high point of 284,000 tons had been reached in 1932, and the figure had exceeded 200,000 tons in following years.

Particularly striking was the amount of petrol that had been conveyed on the river. In 1927-28 less than 5,000 tons had been carried on the Trent, but 1934-35 had seen over 111,000 tons of this increasingly important commodity conveyed by the river.

The Trent was now navigable all the year round, from Nottingham to the sea. The canal network also allowed first class motor or steam barge services to London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, and other cities.

The handbook considered that Nottingham was particularly well placed on the nation’s transport map. It possessed first class railway connections, was on a number of important roads, and, especially significantly in this context, stood on the bank of the Trent. This gave it convenient access to Hull, Goole, Immingham and Grimsby.

The Trent Navigation ran an efficient and large fleet of vessels, which gave a quick and regular service, and offered ‘cheap transportation’. High powered tugs ran daily from the Humber to Nottingham, hauling trains of barges loaded with raw materials from the coast to the Midlands. From here they returned with the manufactures of the Nottingham region for shipment along the North Sea coast or abroad. Modem self-propelled barges powered by internal combustion engines were also available; these were able to go right alongside ships in dock to take on board or unload cargo, and so to keep transport costs to a minimum.

Here in Nottingham, the wharves of the Trent Navigation Co. and Nottingham Corporation both had up-to-date plant and equipment. At its Wilford Bridge Wharf. some way upstream from Trent Lane, a forty ton crane permitted the loading of fully-assembled railway carriages, made by Metro-Cammell in the Meadows, for shipment abroad.

(Not all these carriages, though, were for abroad. Some went to the London Underground, and years afterwards, in 1967, to the Isle of Wight. This writer remembers boarding a train at Brading on the Island in the early 1980s, and seeing the maker’s plate proclaiming that the carriage had been made in Nottingham).

Goods loaded on to barges at Hull often arrived in Nottingham only two days later, allowing the handbook to assert that carriage by water was not only inexpensive, but also prompt.

Trent Navigation distributed from Nottingham by road, rail or water, depending on which was the most economical route for the merchandise being handled. Grain, paper, sugar, and canned and other foods were all carried in large amounts.

All of the above optimism, confidence and bustle is now seventy years or more in the past, and reads like something from a much more distant age. In 1998 I went to look at the Trent Lane depot from the West Bridgford side. Having walked to the riverside through the water meadows at Lady Bay, I enjoyed a pleasant stroll up river, noting among other things the site of the old Riverside Pleasure Park (also at the end of Trent Lane), where I had experienced my first ‘seaside’ holiday.

Photographs taken about 1941 at this highly acclaimed resort show, not only your writer with bucket, spade and bathing costume, but also the wind pump which until very recently existed at the marina on this site - it may even still be there. And while you can, go and look at the side wall of the first house on the left in Trent Lane, across the road from the Earl Manvers pub. If you look hard enough, you will just make out the remains of a painted advertisement for the Pleasure Park.

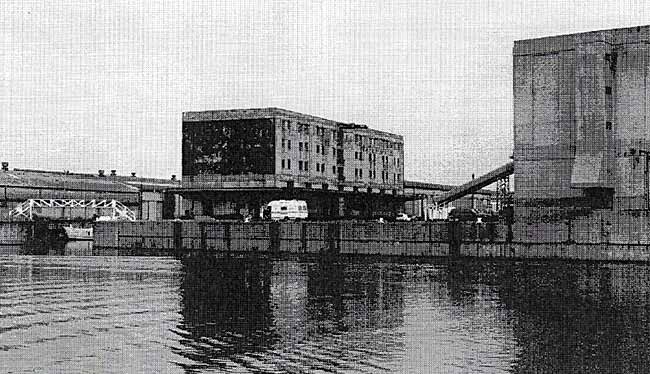

From across the river the old Trent Navigation depot had become a rather eerie sight. I saw only three people as I took some photos from the Bridgford bank, although a couple of vans and a caravan on one of the wharves were minor signs of life. But the only water traffic I saw were two scullers on their way downstream., and a canoeist who paddled into and out of the basin.

The old riverside will be quite obliterated before long, but one hopes it will not be totally forgotten. It is hard to escape the feeling that Nottingham’s waterway is, in this first decade of the 21st century, ludicrously underused, both for industrial and leisure purposes. The Trent Navigation premises in Trent Lane are just one of the lost industries of that part of Sneinton lying near the river: Bitterling’s ‘butchers’ outfitters, hide and skin merchants, and sausage skin manufacturers’: Tumey’s leather works: the Railway and General Engineering Co.: the Co-op bakery and cheese factory. What a mixture of agreeable aromas and foul smells they made.

The Trent Lane complex from the West Bridgford bank of the Trent, 1998

The Trent Lane complex from the West Bridgford bank of the Trent, 1998 Plan of Nottingham Corporation Trent Navigation Terminal Station

Plan of Nottingham Corporation Trent Navigation Terminal Station< Previous