< Previous

"Now for JACKY MUSTERS":

The Reform Riots and their aftermath in Sneinton

By Stephen Best

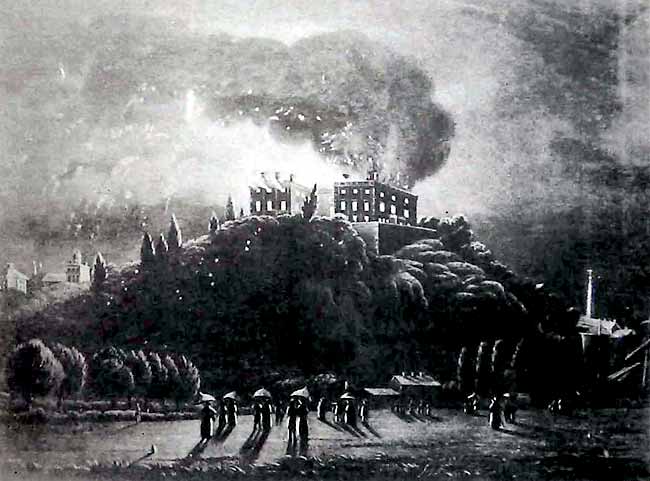

NOTTINGHAM CASTLE IN FLAMES: A contemporary engraving.

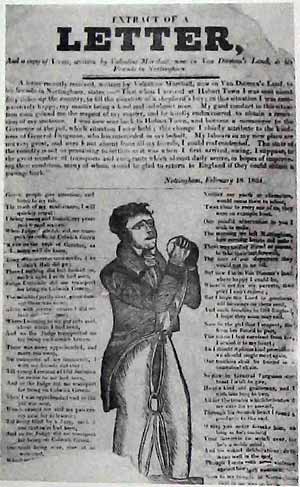

NOTTINGHAM CASTLE IN FLAMES: A contemporary engraving.  THE LETTER AND VERSES written by Valentine Marshall, as sold on the streets of Nottingham in 1834.

THE LETTER AND VERSES written by Valentine Marshall, as sold on the streets of Nottingham in 1834.In 1834 a striking broadsheet appeared for sale on Nottingham’s streets. It portrayed a manacled young man raising his hands in supplication, and announced itself to be an 'Extract of a letter, and a copy of verses, written by Valentine Marshall, now in Van Dieman's Land, to his friends in Nottingham'. In his letter Marshall told of his experiences as a transported convict in what is now Tasmania. The verses related how he came to be there, and protested his innocence.

'Good people give attention, and listen to my tale,

The truth of my misfortunes, I will quickly reveal;

I being young and foolish, my years just turned sixteen,

When Judge Littledale did me transport for being on Colwick Green'.

Valentine Marshall went on to describe how, 'with several thousands', he had been present at Colwick Hall when the home of John Musters was attacked and fired during the Reform Riots in October 1831. According to his verses, he 'nothing did but looked on', returning home and saying nothing to his parents about the incident;

'Till young Freeman of Old Sneinton

he swore he had me seen

And so the Judge did me transport

for being on Colwick Green'.

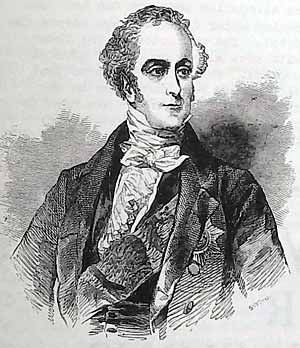

What had happened at Colwick, and why were the people in so angry a mood? In a word, the burning issue of the day was Reform. The movement for Parliamentary Reform had been gathering momentum for some time, with the middle and working classes demanding the right to have some say in the government of the country. Parliament consisted of landowners and their nominees, with some MPs representing 'rotten boroughs' which contained only half a dozen electors; one or two seats, indeed, were bereft of any inhabitants at all. In sharp contrast, some great and thriving towns, such as Sheffield and Birmingham, had no MPs of their own. Hand in hand with this state of affairs existed the tiny franchise, with the landowning classes controlling much of the vote. After much infighting the Whig Prime Minister, Earl Grey, gave his blessing to a modified Reform Bill which would extend the franchise in the counties to most farmers, while limiting the franchise in towns to occupiers of houses rated at £10 a year or more, to the urban middle classes in fact. The Bill also proposed a redistribution of Parliamentary seats, with the rotten boroughs losing their MPs. The seats thus gained were to be used in improving the representation of the counties or providing MPs for the new industrial centres. This Bill was passed by the Commons, but in October 1831 was thrown out by the Lords. So the stage was set for trouble in Nottingham, and most of this was to be focused upon the person of Henry Pelham Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle. This nobleman had recently presented an anti-Reform petition to the Lords and had over the years become identified as a dyed-in-the-wool reactionary. Once, at Newark, he had evicted thirty-seven of his tenants for voting against his nominee, and had answered criticism of this act with the rejoinder 'is it to be presumed that I am not to do what I will with my own?' On another occasion he declared, with no apparent sense of shame, 'I have only to show my face to cause a riot'. The Duke was the owner of Nottingham Castle, by 1831 unoccupied and semi-derelict, but still an impressive symbol of power and privilege as it dominated the town, whose Whig Corporation, in the face of Tory opposition, was active in support of the popular cause of Reform.

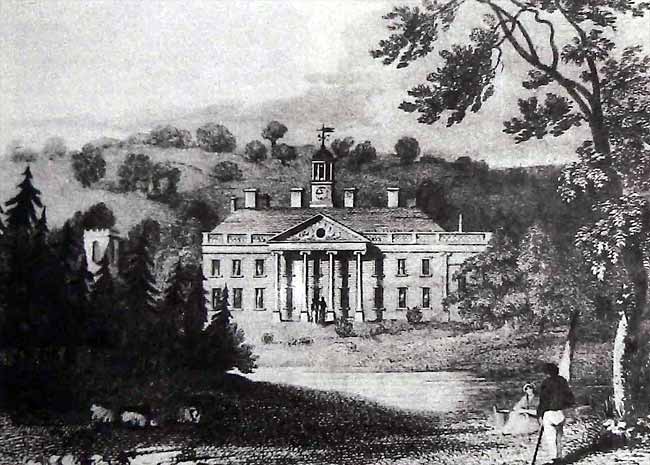

On the evening of Saturday, 8th October, news of the Lords' rejection of the Reform Bill reached Nottingham with the arrival from London of Pickford’s van. The Mayor was immediately asked to arrange a public meeting, and promised that one would take place on the Monday. When, on Sunday the news from Parliament was confirmed, the trouble began. Windows were smashed in premises whose owners were suspected of being against Reform, and the Riot Act was read. On Monday the 10th, the protest meeting was held, but as it dispersed all semblance of order vanished. Nottingham was packed with visitors to Goose Fair, some of whom were undoubtedly pickpockets and other petty criminals. Anger and resentment, assisted by the effects of drink, inflamed the crowd, and before long mobs were wandering through Nottingham. Although there must have been some disappointed Reformers in the crowd, the general character of the rioters was such that one witness described them as 'the very dregs of society', and it does seem probable that habitual thieves and villains were more responsible for the outrages in Nottingham than were Parliamentary Reformers. The first local landowner to suffer was John Musters of Colwick Hall, a leading Tory magistrate and a severe enforcer of the poaching laws. Shortly before dusk, in the words of the Nottingham Review, 'a body of sturdy youths and young men passed up the Snenton road, and at Notintone-place tore down a long range of iron pallisades, with which they armed themselves'. Bearing these primitive but effective spears the mob pressed on towards Colwick, leaving one of Sneinton's fashionable streets denuded of its garden railings. (This incident was soon to have a curious echo when the iron railings of the newly built Collin's Almshouses in Carrington Street were altered by a local blacksmith to prevent their being uprooted in the event of a similar disturbance.) The Review went on to recount events at Colwick Hall. 'They then proceeded to Colwick, reinforced by continual arrivals from the lower parts of the town: here the windows were all broken, the furniture split or torn in pieces and thrown into heaps, to which they set fire.' All the members of the family, apart from John Musters, were at home. Mrs. Musters, who as Mary Chaworth had been Byron's boyhood sweetheart, was in the drawing room with her daughter and a French visitor when the attackers arrived.

COLWICK HALL IN THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY. An illustration from Laird’s 'Beauties of England and Wales’, published in 1813.

COLWICK HALL IN THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY. An illustration from Laird’s 'Beauties of England and Wales’, published in 1813.She had been ill in bed not long before, but, with her companions, ran outside and hid, despite pouring rain, in the nearby shrubbery, while the rioters did their bungling best to burn down her home. Mrs. Musters was to die during the following year, and it was widely argued that the shock and exposure she had suffered hastened her early end. The Hall was fired in several places, and it was alleged that some members of the mob were heard to say afterwards that 'it was no fault of theirs that the place was not burnt down'. An example of their over-eagerness to destroy Colwick Hall was the throwing of a feather bed on to one blazing heap of wreckage; this smothered the flames rather than fed them, and so put out this particular seat of the fire. The Hall was soon abandoned by the rioters, its furniture wrecked, many paintings ruined (including one by Reynolds), and a quantity of food and drink looted. Some of the miscreants stole clothing belonging to the Musters family, putting these garments on under their own clothes. The mob made its way back into Nottingham, some of its members venting their anger on the House of Correction, while a larger group went on to wreak vengeance on the Duke of Newcastle by burning down Nottingham Castle in what must have been one of the most dramatic episodes in the town's history. The third major outrage of the Reform Riots occurred next day, when a silk mill at Beeston belonging to William Lowe (another prominent Tory) was destroyed by fire.

THE FOURTH DUKE OF NEWCASTLE as portrayed in the 'Illustrated London News' of January 18th, 1851.

THE FOURTH DUKE OF NEWCASTLE as portrayed in the 'Illustrated London News' of January 18th, 1851.The following weeks saw a great deal of official activity, with the authorities busy rounding up those accused of committing offences. The Duke of Newcastle, convinced as always of the absolute rightness of his own beliefs, was enraged. He begged the Government to appoint him Chairman of a Special Commission set up to punish the offenders, but someone with more common sense than the Duke possessed saw to it that His Grace was not given the opportunity of acting as a judge in an issue involving his own interests and feelings so deeply. The Duke did, however, gain some revenge by obliging the ratepayers of the Hundred of Broxtowe, which included the Castle, to pay him £21,000 in compensation. Places as far off as Mansfield had to contribute, as well as much closer villages like Arnold, Lenton, Basford and Bulwell.

On January 4th 1832 two judges arrived in Nottingham to preside over the Special Assize for the trying of the accused. A Grand Jury of local landowners and gentry was sworn in. The first trial was that of the men involved in burning Lowe's silk mill; six were found guilty, but they had to wait until the end of the Assize to hear their sentences. On January 11th, the trial of Charles Berkins, Valentine Marshall and Thomas Whittaker began.

The prosecution alleged that they 'with others, on the 10th of October, feloniously and maliciously set fire to Colwick Hall, the seat of John Musters, Esq.' During the proceedings John Freeman, a shoemaker of Old Sneinton, stated in evidence that he saw Valentine Marshall 'against the oval gate opposite the house; the gate was thrown down, and he was walking backwards and forward with a piece of wooden fence in his hand'. In what seems a very unconvincing statement Freeman said 'I don't know who was the first person I told that Marshall was there; I do not know that I mentioned it till I went before the magistrates; it was a fortnight or three weeks after......' The next witness to incriminate Valentine Marshall was Richard Balderson, an outdoor servant at Colwick Hall, and brother of the lady whose recollections of Sneinton Hermitage appeared in Sneinton Magazine No.15. Balderson said that he saw Marshall 'in the mob at the front of the house: I had known him before'. Speaking in his own defence the boy Marshall, by now 17 years old, declared 'I was never nigh Snenton that day'. Since he lived in New Street, off Fisher Gate, very close to where the Stag and Pheasant is now, this may have been something of an exaggeration, but the poor lad was doubtless in mortal terror during the trial. He admitted to having attended the protest meeting in the town, and said that he was on the Bridgefoot (now Plumptre Square) when he heard that the Castle was ablaze, and went to see the fire. Rebecca Marshall, Valentine's mother, stated that her son had dined at home in New Street, and had been indoors until it was nearly dark. A neighbour who lived two doors away testified that the young man had bought a pennyworth of apples from her a little after six on the day in question, while the family's next-door neighbour said that Marshall had been in her house between 7 and 8 in the evening. Thomas Whittaker, another of the accused, admitted that he had been with the mob in Nottingham, but was adamant that he had not been at Colwick. Near Sneinton Church, he said, 'I saw them pull down some palisades, and I heard them say "Now for Jacky Musters" and I thought that perhaps something serious might happen, and I turned back again to Nottingham'. The most damning evidence against Charles Berkins, the third man on trial for offences at Colwick, came from a young man who claimed to have seen Berkins take off his shirt inside the Hall, set fire to it, and push it under a bed. Although the Judge's summing up lasted over two and a quarter hours, the jury was out for only five minutes before returning verdicts of guilty against all three. They, too, had to wait until the end of the Assize before hearing their fate. The remaining cases in the Special Assize all resulted in acquittals: in the matter of the attack on Nottingham Castle the cases against all but one man were dropped, and he was found not guilty as there was insufficient evidence against him.

On Saturday, January 14th came the sentencing of the nine men found guilty of offences during the Reform Riots. Mr. Justice Littledale passed sentence of death on them all, but told four of the men, including Valentine Marshall, that they would be recommended to His Majesty's Mercy. On hearing this, the four are all said to have exclaimed 'Thank you, oh thank you, my Lords'. The only participant in the Colwick Hall attack to be denied a recommendation to mercy was Charles Berkins.

The Nottingham Review, ever a staunch ally of Reform, was scathing about the whole business. While agreeing that serious offences had been committed, it was steadfast in its belief that the death penalty should only be invoked in the case of murder. The Review was very concerned about the harsh conditions under which the prisoners had been kept, repeating an allegation that one man had been denied water for five days before the trial. The character of the Crown witnesses also came in for adverse comment. The Review observed that Berkins had been convicted on the evidence of a youth who had been in prison at least twice, and whose brothers had said that they would not believe anything he said, even on oath. 25,000 people signed a petition against the death sentences, but only two of the five condemned men were reprieved. One of these was Charles Berkins, so in the end none of the attackers, or alleged attackers, of Colwick Hall was executed.

So Valentine Marshall and the five other survivors were transported for life. They may have been quite forgotten until in 1834 Valentine's letter and verses were printed in Nottingham. What this boy from a tiny house on the edge of Sneinton must have thought of Van Diemen's Land can only be conjectured, but he recorded that he had been at first sent up country to work as a shepherd's boy. In this, he said, 'I was comparatively happy, my master being a kind and indulgent man'. Good conduct earned him some remission of sentence, and he had obtained a post as a messenger to the governor of Hobart Jail. 'Were I not absent from all my friends', he declared, 'I could rest content'. Valentine Marshall was never to return to Nottingham, but it may be that he enjoyed a tolerable life in a far healthier place than Victorian Nottingham.

But we must return to 1832. With ironic swiftness the Reform Bill was passed, at its third reading, by the Lords. It was just four months after the hangings of the three men who had obtained no reprieve. Nottingham was determined to celebrate 'The Triumph of Reform', and Sneinton had its own festivities on July 16th. The Radical Nottingham Review devoted two whole columns to this event. Sneinton, said its reporter, 'was a scene of gaiety and festive enjoyment never before witnessed in that respectable and populous suburb.' South Street, off Haywood Street in New Sneinton, was bedecked with flags, and three hundred revellers sat down to an open-air public dinner, with beef and mutton the main attractions. Mr. Olive Moore, lace maker, of Haywood Street, proposed the health of the King, and was followed by Thomas Ragg, also of Haywood Street. Ragg was a self-educated stocking maker who worked his way up to become a bookseller's assistant, a prolific writer of Christian verse and, in later life, a Church of England clergyman. (More about Thomas Ragg can be found in 'Two Sneinton men of verse' in Sneinton Magazine No. 7). He spoke at great length, and with Evangelical fervour, pointing out the mistakes that had been made during the French Revolution, but which must not be allowed to happen in this country. Ragg ended with a thunderous declaration. 'Power is an Ordinance of God, and he who resisteth the power - yea, he who resisteth the legal, and constitutional power of the people, resisteth God'. All then drank the Queen's health.

While all this was going on at South Street, the men of Old Sneinton were enjoying 'a beautiful dinner' under an awning erected in the street 'fronting Morley’s public house'. This was the Old Wrestlers, now on the corner of Sneinton Hollows and Castle Street, and currently awaiting renovation. Here too the street was brightened by 'a profusion of flowers, tri-coloured flags, banners and union jacks'. To prevent gate-crashing' a peaceful barricade was thrown across the road'. At four o'clock in the afternoon three parties of men, from New Sneinton, Notintone Place and Old Sneinton, met near the New Inn, Sneinton Road, and after marching in procession through Sneinton with banners, paraded through the Hermitage to Nottingham, returning at about 6.00 p.m. This procession, thought the Nottingham Review, would be engraved 'on the memory of every beholder to the latest period of his life'.

Readers who have felt indignation about the men-only nature of the Old Sneinton feast will be glad to note that, while the males were engaged in their parade, 140 female inhabitants partook of afternoon tea, and eighty children 'were regaled with plum cake and ale at the Fox’. The women and children of New Sneinton also enjoyed a tea while their men were taking part in the march, some three hundred of them sitting down to a spread there. The evening festivites at New Sneinton were interrupted by an 'influx of strangers and children', which obliged the locals to retire to neighbouring pubs, where they consumed ham sandwiches and ale, provided by subscription. Up the road at the Fox, 'the village lads and lasses' danced into the night. On the following day two large parties of Sneinton residents dined and took tea at the White Swan, Sneinton Hermitage, and at the New Inn. The Nottingham Review, in extolling 'the recent glorious triumph of the people over a boroughmongering oligarchy', ended its report in minatory fashion. Mentioning that the many children who had attended the Sneinton festivities would never forget the day, it warned 'Woe be to future governments who withhold from them the rights their fathers struggled to obtain'.

But was the Reform Act really such a triumph for the common man? Would Valentine Marshall have felt that all had been worthwhile when he heard the news in Van Diemen's Land? The fact was that the ruling classes had recognised the necessity of a limited amount of Reform if further discontent was to be avoided. Although the middle classes, especially in towns, had done quite well out of the Act, the aspirations of the working classes remained unfulfilled. Out of a population of some 50,000, Nottingham's electorate remained about 5,000, and in the country as a whole five out of six adult males were still without the vote. Women, of course, had to wait until well into the twentieth century before they got the Parliamentary vote.

By 1878 the burnt out Castle had been rebuilt and opened as a Municipal Museum and Art Gallery, and only the riot proof railings of the Carrington Street almshouses remained as a silent reminder of the day that had changed Valentine Marshall’s life.

I THANK RICHARD PRESTON for reading this article in manuscript and offering valuable help and advice.

STEPHEN BEST

ALL ILLUSTRATIONS BY COURTESY OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY LIBRARY, LOCAL STUDIES LIBRARY.

< Previous