< Previous

'A LOW UNPRETENDING

BUILDING' :

The story of St. Luke's Church

By Stephen Best

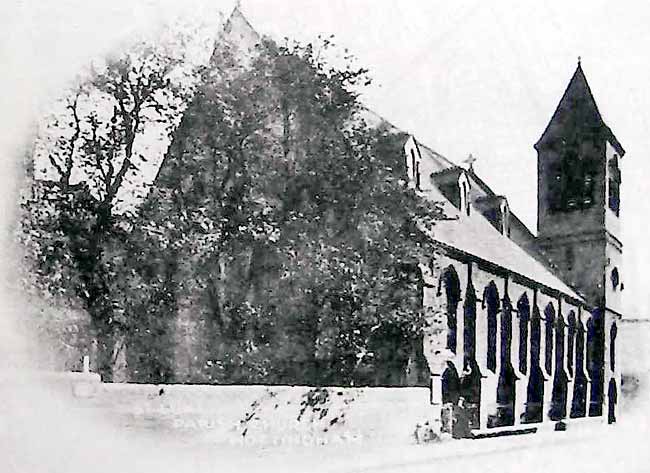

THE CHURCH from the junction of Longden Street and St. Luke’s Street.

THE CHURCH from the junction of Longden Street and St. Luke’s Street.Near the bottom of Carlton Road there survives a link with an almost forgotten ingredient of Sneinton's history. At a street corner, just opposite the end of Walker Street, stands a building now occupied by the Tennant Rubber Company. With its attractive timbered gables and the Gothic lights in some of its upper windows the structure has about it an air of Victorian pomp and officialdom. What can it have been? The answer lies in the name of the side street -St. Luke’s Street - for what we are looking at is the former St. Luke’s Parochial School. A few yards away, on the corner now taken up by the City Mission, stood for just over sixty years St. Luke’s church itself.

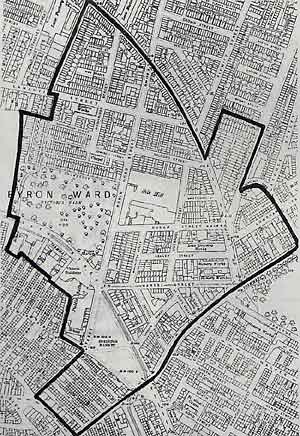

THE EXTENT OF ST. LUKE'S PARISH, 1913.

THE EXTENT OF ST. LUKE'S PARISH, 1913.St. Luke's was conceived in the early 1860s when the spread of Nottingham and the increase in the town's population made the provision of more churches an urgent priority. Part of the very large parish of St. Mary’s was designated the district of St. Luke, and on 2nd July, 1861 the foundation stone of the new church was laid by Thomas Adams, the Nottingham lace manufacturer and public benefactor. The site on the corner of Carlton Road and Woodborough Street (as St. Luke's Street was then named) was close to the streets which were rapidly springing up on the old Clayfield, released for building after the 1845 Nottingham Enclosure Act. The Nottingham Review, in reporting the stone-laying, related that Mr. Adams 'delivered an apposite address to the assemblage present'. The paper also noted that the church was to be in the Early English style and was expected to hold 900 people. Construction was to be in the hands of a Mr. Garland.

Building work evidently got under way soon afterwards, but this operation was to suffer more than its fair share of setbacks. The contractor, Thomas Garland of St. Ann’s Well Road, became bankrupt and work was held up until he was replaced by the firm of C.C. & A. Dennett of Station Street, Nottingham. In 1862 the partially-built church was badly damaged in a gale: the gable ends had been erected and some of the roof beams were already in position when the wind struck, bringing timber and masonry crashing down. This mishap caused the architect, Robert Jalland of Castle Gate, to reconsider his design for the roof. He decided eventually to use big roof trusses which spanned the width of the building and were carried vertically down the walls to the foundations. This resulted in a wide, barn-like interior without any pillars to obscure the view of the congregation. Jalland may be thought a brave man to have taken on another church in Nottingham at all after the roasting accorded to his St. Mark’s, Windsor Street, by the architectural press in the mid-1850s, and his labours at St. Luke’s were greeted with only the faintest of praise when that church was consecrated by Dr. Jackson, the Bishop of Lincoln, on February 24th, 1863. The Nottingham Review’s only comment on the merits of the building was 'It has been erected for a practical purpose, and more attention has been paid to obtaining accommodation in space than to architectural beauty'. The Review did, however, concede that 'It is situated in a populous and rising locality at a considerable distance from any other religious house and will consequently be of great service'. The Nottingham Journal had rather more to say about St. Luke's, describing Mr. Jalland's difficulties and even suggesting that 'At one time some doubts were entertained as to the soundness of the structure'. The paper was, happily, able to reassure its readers that 'those doubts have been entirely removed by the report of the surveyor appointed by the Bishop'. The Journal went on to list the main features of the new church without exactly heaping compliments upon Jalland’s head. St. Luke's it considered 'in its exterior a low unpretending building', but it was admitted that the interior presented 'a certain aspect of comfort and lightness'. Evidently the reporter found that even this impression faded upon closer inspection, for, he continued, 'The open benches are somewhat too low for the comfort of the occupants'. In its most cordial comment on Mr. Jalland's efforts the Journal recognised that his main concern had been 'to obtain the largest unencumbered accommodation at a moderate cost, and he has succeeded admirably'. Despite this praise St. Luke's did not begin its career unfettered by debts; the building had been financed by public subscription, but the estimate of £2,977 had been exceeded by some six or seven hundred pounds.

Judging from the evidence of old photographs, St. Luke's does indeed seem to have been a plain building.

THE INTERIOR OF THE CHURCH, looking east.

THE INTERIOR OF THE CHURCH, looking east.Its main external feature was a south-east tower with pyramid roof, while a polygonal apse faced Carlton Road. The St. Luke's Street frontage had a range of tall windows between prominent buttresses, while the roof was enlivened by a row of dormer windows. Behind the church was the vicarage garden, with some pleasant trees. St. Luke's had a severe Low Church interior, with a stone pulpit and little in the way of decoration, apparently, apart from some stencilling on the walls and ceiling of the apse.

In its report of the consecration, the Nottingham Journal had one look into the future. 'It is proposed, we understand, to erect new schools as soon as the funds will permit - a result which all the friends of the undertaking will hail with satisfaction.' It was not long before this hope became a reality, the corner-stone of the school building being laid on Easter Monday 1864 by James Holwell Lee. Mr. Lee, who paid for the school out of his own pocket, was owner of the hosiery firm of Lee and Gee, of Alfred Street South. The architect was Frederick Bakewell of Thurland Street, whose new School of Art building in Waverley Street was in course of construction at the time. Of St. Luke's School, the Nottingham Journal noted that 'the building will be in character with the church, and the intended parsonage'. When first opened the school accommodated boys in a big room on the ground floor, with girls and infants upstairs. During the same year the first vicar of St. Luke’s, the Rev. Henry Daniel, decided that a church presence was badly needed in the densely populated southern end of the parish, and he accordingly began a mission in a disused dye-house in Poplar Street. Mention of Poplar Street makes one realise just how large an area of Nottingham was served by St. Luke's at that time. In its earliest days the church district reached from St. Ann's Well Road to Carlton Road, including all the houses between Alfred Street and Bath Street. From Sneinton Market it then ran south to take in the poor area between Carter Gate and Manvers Street, extending as far as the canal and returning up London Road to include Island Street. Only a few months after starting the Poplar Mission Mr. Daniel was dead, and it comes as a vivid reminder of the perils of Victorian town life to read that this vigorous clergyman succumbed to typhoid fever at the age of only 32. A large crowd attended his burial in the St. Mary's cemetery in Bath Street, and such was the respect in which Mr. Daniel was held that the funeral procession was said to have stretched unbroken from St. Luke's church to the burial ground.

Within a very few years of the consecration of St. Luke's, extra accommodation became urgent at both school and church. A gallery was built at the west end of the church, while a new Boys' School was built not far away at the junction of Salford Street and Liverpool Street. Once again St. Luke's was helped by the generosity of a local businessman, the new school being provided by a member of the Windley family, whose silk mill was in Robin Hood Street, almost next door to the school. The departure of the boys from the Carlton Road school enabled the girls and infants to occupy all the space in the original building. Meanwhile the opening of St. Ann's church in 1864 had brought alterations to the boundary of the St. Luke's district, while the consecration in 1879 of St. Philip's, Pennyfoot Street, was to take away a further large piece of the parish. St. Philip's was the culmination of Mr. Daniel's Poplar Mission, and was built as a memorial to that same Thomas Adams who had laid the foundation stone at St. Luke's eighteen years earlier. Finally, in 1888, the establishing of St. Catharine's parish caused St. Luke’s parish to be reduced in size yet again.

The 1890s saw the launching of a parish magazine, extracts from which were to appear in a little booklet published in 1913 to mark the Golden Jubilee of St. Luke's. This forms a valuable source of information about the church, and the present writer is glad to acknowledge his indebtedness to it. The first issue of the magazine, that of January 1891, recorded the founding of a Boys' Brigade company at St. Luke's Boys' School: this was the 5th Nottingham Company, which was later to lapse owing to a shortage of officers. As we shall see, though, the Boys' Brigade was eventually to re-establish, in the most positive way, its connection with St. Luke's. The parish magazine was also able to report that St. Luke's Schools enjoyed a high reputation, the issue for September 1891 claiming that 'Our Infant School, Carlton Road, we have not the slightest hesitation in saying, can compete with any school. The Girls' School was very successful in the last examination, and earned the 'Highest Possible' grant in all subjects. About the Boys' School, Liverpool Street, we need say very little. It has a good name among the parents, and the yearly reports from H.M. Inspector show that it maintains its reputation. The boys receive a sound commercial education, and many of our scholars have turned out successful business men'. Despite this glowing account all was not going smoothly at St. Luke's Schools, and by 1895 the running of them had been taken over by the Nottingham School Board, whose report of that year included this comment. 'We are sorry that two of the old Voluntary Schools of the town - St. Luke's School, with 450 children, and the Arkwright St. Wesleyan School, with 644 - have, under the severe pressure of the present time, found it impossible to maintain themselves upon the old footing. In this way alone 1,094 children have passed to the care of the Board.' The Board's annual reports for the next few years quote from the Inspectors' comments on St. Luke's Schools, some of which bear out the proud claims of the parish magazine. Some pleasant human touches appear; we read, for example, that in 1895-6 'Some boys were not so tidy as they could be and should be', while the following year's report said of the infants, 'They are very kindly treated’. An ominous note for the future of the Schools, though, was struck with the observation that 'the class room in the infants’ school is habitually used for a larger number of scholars than for which it is passed by the Department'. This comment was underlined in 1897-8; 'Considering their confined accommodation they are in excellent order.... The attendance should be reduced or the accommodation increased.' Another major drawback to both of the St. Luke’s school buildings was the absence of any playground, and with the provision of new school premises in Carlton Road and Bath Street the end was in sight for the schools given by Mr. Lee and Mr. Windley. They closed at the turn of the century, the School Board report for 1900-1 offering an appropriate valediction. 'Boys' School - This school is instructed in an earnest and successful manner. The boys are under an excellent influence. Girls' School - The work was highly satisfactory, and the order very good. Infants’ School - The work is very good, and the tone and order are excellent.' If these useful buildings had to close, their teachers could hardly have wished for a better line to accompany the fall of the curtain. The impending closure of the schools had saddened the last days of the church's vicar: the Rev. Edward Rodgers had come to St. Luke's as long ago as 1865, on the death of Mr. Daniel, and died in harness in July 1900 at the age of 80. Parishioners might well have felt that nothing would ever be the same again.

Edwardian England saw many changes in St. Luke's parish. Two vicars came and went, while the area was suffering a serious decline, with a pronounced slump in church attendance. In 1909 it was recorded that there was 'scarcely a church-going family amongst the new residents, and the parish was constantly growing poorer'. Even the vicar felt the need for more salubrious accommodation than was provided by the vicarage in Handel Street, and a site for a new vicarage in Windmill Lane was given by Earl Manvers. This was, however, never to be built, and after the Handel Street premises were sold, the vicar of St. Luke's lived for a year or two at 4 Plantagenet Street before moving to 39 St. Chad’s Road.

In 1910 the Rev. Frank Johnson Taylor became vicar, and in 1913 recorded his impressions of his first three years at the church. The population of the parish had declined by some 500 during the past ten years, and Mr. Taylor clearly found cause for concern. 'In some parts of the parish' he wrote, 'especially in the streets below Sneinton Market, houses continue to change their tenants with amazing frequency.... There still remain about the church a few people whose churchmanship is conscientious, who have worshipped at the church continuously through the changing years, who are always ready to share its burden of work, and to give of their hard-earned wages for its support. Their number within the parish is but small'. One cannot help thinking that Mr. Taylor saw the writing already on the wall for St. Luke’s when he commented, 'In a parish like St. Luke’s, where some streets and yards are occupied by the very poor, the result of the church’s work is not likely to be seen in the addition of permanent members to the congregation in any large numbers. There are some other streets of better houses occupied by artizans and working-people among whom changes are not quite so frequent: but the expectations of all the Vicars of St. Luke’s that these would come forward and attach themselves as regular worshippers to the church which was built for their use, and help to maintain it, have been for the most part disappointed. Visiting among them reveals the fact that the parochial instinct, if it ever existed, is dead'.

Not all, though, was gloom. Mr. Taylor had striven manfully to retain the interest of his congregation; 'a powerful electric long- range lantern’ had been placed in the church’s gallery, and ’Lantern Services' were held, with the words of prayers and hymns, and pictures illustrating the sermon, projected on to a screen fourteen feet across. Temperance work was also going on vigorously at St. Luke's, while perhaps the most encouraging event of all had occurred in late 1912 when the 2nd Nottingham Company of the Boys' Brigade at the Dakeyne Street Lads' Club became officially associated with the parish church, with the vicar becoming its Honorary Chaplain. It was claimed at the time that this was the largest Boys' Brigade company in the world, attracting boys from all over the Sneinton area and beyond. On June 29th, 1913 the band of the Company led a parade of Sunday School children and Brigade members around St. Luke's parish, and so many worshippers attended the subsequent Flower Service that 'the floor of the church was packed from wall to wall, and late comers found room only in the gallery'. By this time the parish had assumed its final, roughly triangular, shape, with its apex at the junction of Sabina Street and Alfred Street, and its base running along Southwell Road and Carlton Road from where Price & Beal's shop now is to the Duke of Cambridge pub at the corner of Clarence Street. The worst housing in the parish was in the streets later cleared for the wholesale market, while some areas, like Stewart Place, were very pleasant.

After the Great War, more and more of Nottingham's inhabitants were moving out of the City's central areas to new homes in the suburbs, leaving old churches in the Inner City with small populations and congregations. Plans were drawn up for the closure of several 'redundant' churches including (inevitably, one feels) St. Luke’s. A leading article in the Nottingham Guardian of July 18th, 1921 reported, 'It is suggested, also, that the church of St. Luke, at which, we believe, a very good work is being done, shall be sold, and the parish united with that of St. Philip's, which has lost a large portion of its population through slum clearances'. In the following January an ecclesiastical inquiry was opened at St. Mary's church vestry into the desirability of uniting several benefices in Nottingham, including St. Luke's and St. Philip's. It was stated that St. Luke's, with seating accommodation for 700, had Sunday morning attendances of between 25 and 30, while most of those who attended Evening Service came from outside the parish. The population of the parish was in fact 3,763, of whom only 25 were on the church electoral roll. St. Philip’s parish, which had once boasted a population of over 4,000, was now down to a mere 300 residents; St. Philip's though, was by far the better of the two church buildings, and was, in addition, much the better attended. The move to unite the benefices was now unstoppable, and an Order in Council of March 21st, 1924 sealed the fate of St. Luke's.

Union was to take place when the benefice became vacant, and when on November 27th of that year the Rev. Frank Taylor was instituted Vicar of Hartington in Derbyshire, St. Luke's church closed.

Demolition work began in October 1925, and was carried out by a Mr. Frank Stell, who had bought the site. Mr. Stell had, before the war, purchased the old vicarage in Handel Street, turned it into 'Vicarage Works', and installed his own pinafore making firm, together with companies engaged in the lace curtain, blouse, and embroidery trades. When asked what he would like to see done with the site of St. Luke's, Mr. Stell gave a reply which, in the light of recent experience, must have seemed wildly optimistic. 'It would give me pleasure if another church was erected on the site', he said. Optimistic or not, Mr. Stell's hopes were not so very far from being realised. Less than a year later, the Nottingham Journal reported the laying of the foundation stone, on the St. Luke's site, of the new hall of the Nottingham City Mission. Begun in 1837 as the Nottingham Town Mission, its purpose had been 'To extend among the inhabitants of Nottingham and its vicinity (especially the poor) the knowledge of the Gospel, irrespective of peculiar tenets with regard to church government, by meetings for prayer and by promoting scriptural education'. The work of the Mission was carried out 'in a liberal and unsectarian spirit, by a regular and systematic visitation of the ignorant, depraved, and wretched districts of the town, to seek and save those who are lost'. Originally a Nonconformist body, the Town Mission had by the 1850s acquired the active support of some Anglican clergy in Nottingham. In 1859 the Town Mission Ragged School in Gedling Street, close to Sneinton Market, was opened and remained under the control of the Mission until it was taken over by the School Board in 1878.

The Ragged School existed 'for the purpose of aiding in the removal of that ignorance, destitution, and vice, so prevalent among the juvenile population; by imparting a scriptural and useful education to those little ones, and by training them in habits of industry and honesty'.

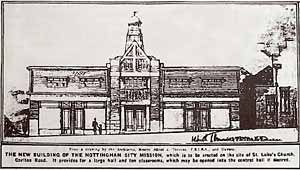

ARCHITECT'S IMPRESSION of the new building for the Nottingham City Mission. (From the Nottingham Guardian, August 10 1926.)

ARCHITECT'S IMPRESSION of the new building for the Nottingham City Mission. (From the Nottingham Guardian, August 10 1926.)The new building for the City Mission was designed by the Nottingham architect A. J. Thraves, who was a few years later to design the Dale Cinema, Sneinton Dale. Thraves's block for the Mission had an attractive frontage to Carlton Road with shops on either side of a central entrance. Above this the gable displayed a stone cross in low relief on decorative brickwork, while a polygonal lantern was a feature of the roof line. Behind the facade lay the Mission Hall itself. The new premises were opened on May 12th, 1927 by the president of the Nottingham City Mission, the Hon. Geoffrey Hope-Morley, who in his address observed that society was 'threatened by disruption and embittered by class hatred'. The Mission, he said, was trying to put right some of the damage caused by neglect of the spiritual life. On behalf of the City the Mayor, Mr. Freckingham, recognised the good work that the Mission was doing, and made a special plea for 'something to be done to interest the boys and girls and so take them off the roads and Market Place on Sundays.’

Almost fifty nine years later the building is still used as the Emmanuel Hall of the City Mission, though the Carlton Road doorway is now blocked and the entrance today is on St. Luke's Street. The old Boys' School in Liverpool Street has disappeared, together with Salford Street itself. In the 1950s, not long before its demolition, it was in use as a Gospel Hall. Frederick Bakewell's school building of 1864 began our look at St. Luke's, and it is fitting that we should end with it. Since its closure it has had a variety of uses, including a long period as P.D.S.A. premises, and more than eighty five years since it was last a school it is still a visual asset to Sneinton. More than that, it serves as a reminder of the days when St. Luke's church and schools played such an important part in the lives of local people.

I would like to end with a personal footnote. The penultimate page of the St. Luke’s marriage registers records the fourth last marriage ever to take place there. This was on Sunday, August 10th, 1924, between George Best, printer, of 6 Dane Street and Mabel Chambers, blouse-machinist, of 18 Robin Hood Street. My uncle died in 1972, but my aunt, who is also my Godmother, still lives in Nottingham. I dedicate to her this fragment of history of St. Luke’s.

< Previous