< Previous

STEPHEN BEST TELLS . . . . . TALES FROM St STEPHEN'S CHURCHYARD :

No. l: C.N.Wright and his family

By Stephen Best

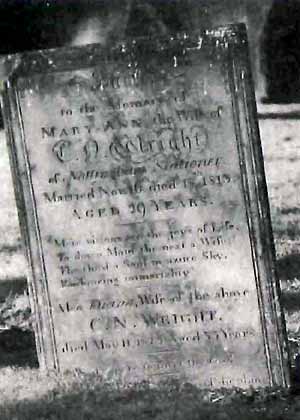

Among the gravestones in Sneinton churchyard is one which tells a sad story and provides us with a puzzle. This headstone, of slate, stands inconspicuously near the north east corner of the church, not far from the grave of George Green. The clearly legible inscription reads as follows:

'Sacred to the memory of

Mary-Ann, the wife of C. N. Wright of Nottingham, stationer.

Married November 16th, died 18th, 1813; aged 29 years.

"Mere visions are the joys of life

Today a maid, the next a wife,

The third a soul in azure sky,

Embracing immortality!

Also Diana, wife of the above

C. N. Wright,

died May 11th, 1823, aged 33 years.'

There may be more carved on the stone, but vigorous poking about in the grass and earth at its foot has failed to reveal any further inscription, and merely earned for me the scandalised gaze of a busload of passengers at the nearby stop. Whether or not the stone has more to tell, we already know enough to realise that C. N. Wright and his wives received more than their fair share of ill-luck.

Christopher Norton Wright was well-known for many years as a bookseller and stationer in Nottingham, and anyone interested in Victorian Nottingham will be familiar with the series of Wright’s directories published between 1854 and 1920 by Wright and his successors. At the time of his first wife's death C. N. Wright had a bookselling business in Bridlesmith Gate, and the brief story of their marriage is told in the Nottingham newspapers of the day. The Nottingham Review of November 19th, 1813 carried the following announcement in its 'Marriages' column: 'On Tuesday last the 16th instant, at St. Peter's Church, Mr. Christopher Wright, Stationer, of Bridlesmith Gate, to Miss Mary Ann Young, of Fore Street, Cripple-gate, London. Since the foregoing, we have received the affecting intelligence of the death of Mrs. Wright, occasioned by taking cold on the day of her marriage, which brought on an inflammation, and last night terminated her mortal existence.' Mary Ann Wright thus achieved the melancholy distinction of having a wedding notice and death notice in one. The Nottingham Journal, published the same week, did manage to get the events into separate notices: that of the marriage was identical to the Review's report, but the death announcement gave rather more detail. 'Last night, of an inflammation in her bowels, Mrs. Wright, wife of Mr. C. Wright, bookseller, an awful example of the mutability of human enjoyment, having been married only on Tuesday morning last! During the short time she had resided in Nottingham, she had gained by her sweetness of temper and suavity of manners, the good will and esteem of all in the circle of her acquaintance.'

The town, no doubt, sympathised with the young widower, hoping that he would in time find lasting happiness, but, as the Sneinton headstone records, he was to lose another young wife less than ten years afterwards. Mrs. Diana Wright's death was reported in the Review of May 16th, 1823: 'On Sunday aged 34, Mrs. Wright, wife of Mr. C. N. Wright, bookseller, Chapel Bar. She had borne a long affliction, with patient resignation, and her memory will be precious to her surviving friends.'

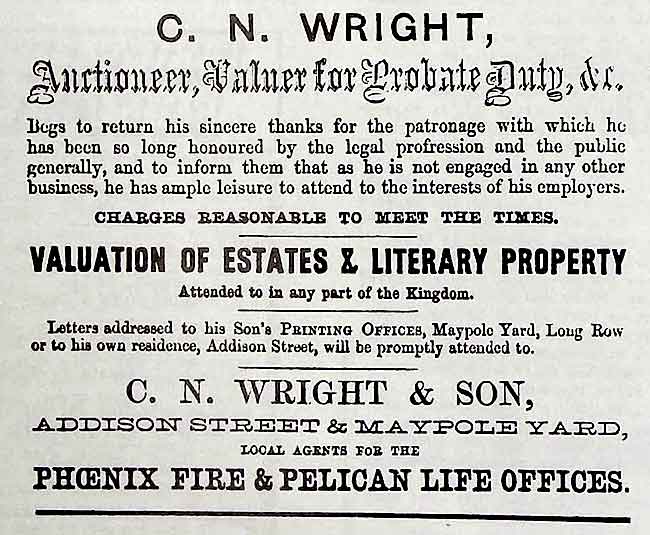

Christopher Norton Wright was to live on for over half a century, enjoying, as we shall see, a successful business career, and experiencing varied fortune in his personal life. Between his marriages he had moved to Chapel Bar, where in 1825 he was a bookseller, auctioneer and dealer in wines and teas, moving soon afterwards to Long Row East. Here he remained for some thirty years, multifariously engaged as a 'bookseller, printer, stationer and binder, auctioneer and appraiser'. In the late 1850s he moved his business to Lister Gate, and acquired one of the comfortable new houses in Addison Street. In 1862 C. N. Wright placed an advertisement in the directory published under his name, stating that although he was otherwise retired he was still active and available as an auctioneer and valuer. This energetic old gentleman died at his home, 50 Addison Street, in 1875.

What makes Christopher Norton Wright's life the more interesting is that he compiled an autobiography. One of his descendants discovered many years afterwards a stack of notebooks covering the years up to 1871: these were edited, and published in 1969 under the title 'No hero, I confess'. I turned to this book hoping to find out something of the background to the sad gravestone in Sneinton churchyard, but, instead of enlightenment, I found only confusion, and realised that C. N. Wright’s memoirs posed more questions than they answered.

As Wright himself tells it, this is the outline of his life. He was born, he says, on March 6th, 1790 at Fazeley in Staffordshire, though it will be demonstrated that this date cannot be correct. After a very eventful early life he arrived in Nottingham in 1806 to assist his father, who had gone into partnership with an auctioneer named Hall. Within a year Christopher Norton Wright was a market stallholder and a travelling vendor of books, knives, scissors and braces, and he very soon set up as a bookseller, adding a circulating library and news room to his enterprises. When he was 24, he relates, he decided that he ought 'to marry to my financial advantage'. Wishing also to be able to love his future wife, he consulted a friend who arranged a tea party for Wright to meet a likely lady. Here he became acquainted with Miss Young. As he was married in 1813, and claims to have been 24 at the time, he cannot possibly have been born as late as 1790. This discrepancy can, one supposes, easily be dismissed as a slip of the memory, but what is much more surprising is that Wright gets his first wife's Christian name wrong, referring to her throughout as Sophia, rather than Mary Ann. Could this have been a pet name, or was he mixed up, or did he have another reason? We may get a clue later. His courtship of Miss Young was a swift one, with Christopher Norton Wright proposing within a week. His account of their marriage and his wife's death from, it appears, acute appendicitis, is a touching one, though according to Wright she died on their wedding night. He confesses that 'I did not love her to distraction, but she filled me with desire'. Through her will C. N. Wright received 'a well-invested income of eight hundred pounds a year', and not surprisingly the lawyer was clearly of the opinion that he had married Miss Young for her money. Wright's grief was softened by the comforting reflection that at least next time he would be able to marry for love alone. Following his purchase of a property on Long Row a year or so after Mary Ann's death, Christopher met the lady who was to become the second Mrs. Wright. This was Mrs. Diana Holme, the young widow of a husband some forty years her senior. According to Wright she was only 18 at the time of their meeting, but once again he must be wide of the mark. He tells of her coming into his shop to enquire about a book; she 'lifted her veil and disclosed a countenance so enchanting that I drew a sudden quick breath and held it'. Utterly smitten, Wright found an excuse to visit her and it was not long before he proposed. Diana astonished him by confiding to him that her grandmother had been one of Louis XV's courtesans and that her mother was the issue of their illicit union. She in turn became mistress of a French nobleman, and Diana was their child. Diana was, according to Wright, packed off to England as a little girl to attend an Anglican convent. I do not know how this could have been possible, since as far as one can discover there were no Anglican religious houses before the 1840s.

Married again, Wright found his business flourishing, and he felt that his standing improved when he was commissioned to buy books at sales on behalf of the Duke of Sussex, whom he had met at Newstead Abbey. The sixth son of George III, the Duke was a friend of Colonel Wildman, who had purchased Newstead from the poet Byron. C. N. Wright was glad to find the Duke's cheques always honoured by the bank; other, less fortunate creditors used to find it harder to get payment from this chronically hard-up aristocrat.

In 'No hero, I confess', Wright records the birth of his first daughter, Mary Anne, on 'a golden September morning'. He also relates that he realised with a start that it was the same date as his first wife's death, but, since we know that she died in November, this is a puzzle. At all events, when he saw that the child was safely delivered, C. N. Wright, walked, so he tells, with a bunch of roses from his garden 'to the cemetery' where the first Mrs. Wright was buried, and placed the flowers on her grave. He records that the walk took him half an hour; a reasonable time for a pre-occupied man to get from Chapel Bar to Sneinton churchyard.

The child Mary Anne was not destined for a long life: while only a small girl she died of a fever. Shortly after this Diana Wright suffered a miscarriage and within three months followed her daughter to the grave, where, according to Wright's autobiography 'they lie together'. So died the second of the Mrs. Wrights to be commemorated on the headstone at Sneinton.

In his memoirs Christopher Norton Wright goes on to relate how, after an interval of several years, he then met and married a Miss Mary Brettell, who kept a school at Erdington, near Birmingham. The first child of this marriage, Christopher Norton, was born, according to Wright, on August 7th, 1827, and by the beginning of 1831 he and his wife were 'the proud parents of four children: Norton, Walter, Henry and little Eliza'. In October of that year the Reform riots broke out in Nottingham, and C. N. Wright’s premises were picked out by the rioters, Wright being one of a group of prominent citizens who had signed an anti-Reform petition. The newspaper reports that on the evening of Sunday, October 9th 'the next attack made by the mob was on the shop of Mr. C. N. Wright, bookseller, on the Long Row; after a few squares of glass had been broken, some youths seized parts of the stalls that were lying about in the Market-place, and using them as battering rams, speedily burst in the shutters of the shop, and completely demolished glass, windowframe, books, prints, and everything within reach; in almost as little time as it takes to narrate it; the amount of the damage must be very considerable. The arrival of the military prevented the total destruction of the contents....' According to Wright every pane of glass in the front of his house was smashed. Mrs. Mary Wright, not surprisingly, fainted under the strain, and he describes how a week or two later she fell ill with influenza, to which she speedily succumbed.

Now in his early forties and three times a widower, Christopher Norton Wright was still optimistic enough to marry again. His fourth wife, Anne Cooke of Fazeley in Staffordshire, was says Wright, nineteen years his junior. This time he was luckier; they were to have over forty years together, and his autobiography closes with the Wrights living contentedly in their 'pleasant small house' in Addison Street.

Enough has already been said to suggest that C. N. Wright made some startling errors of fact in his memoirs. Indeed, a comparison of his recollections with other records suggests that he got precious little correct, and that as an autobiography 'No hero, I confess' has to be treated with the greatest suspicion. The Sneinton parish registers record the burials of 'Mary Ann Wright, 29, Nottingham' on November 22nd, 1813, and of 'Diana Wright, from Nottingham, 31 years' on May 15th, 1823. The newspaper, the register and the headstone all give a different age for Diana Wright, but she must have been at least 24 when Wright fell in love with her, rather than the 18 claimed by him. What the Sneinton registers do not show at all is the burial of the child Mary Anne, who, according to Wright died three months before her mother and shared her grave. It is all very odd, and readers who have persevered this far are warned that the confusion gets worse.

In 'No hero, I confess' Wright clearly states that Christopher Norton, the eldest child of his marriage with Mary Ann Brettell, was born on August 7th, 1827. The brain, therefore, reels a little upon the discovery that the said Christopher Norton was baptised at St. Mary's, Nottingham, on November 12th, 1826, and that as early as March 20th, 1825 Mary Ann Brettell Wright, daughter of 'Christopher Norton and Mary Anne Wright of Long Row', was baptised at the same church. Genealogical records also show that in November 1829 these same two children were baptised at Friar Lane Chapel, Nottingham, along with their sister Caroline Rose. Friar Lane Independent Chapel had been opened in 1828 as the result of the secession of a number of members of the congregation at St. James's Street Congregational Chapel, and it is, one supposes, possible that the entire Wright family was converted to Nonconformity. That is as may be: what is something of a shaker is one's realisation that C. N. Wright cannot remember which of his children were living at the start of 1831. We know that Mary Ann and Caroline Rose were baptised in 1829, so why did Wright not mention them as two of his four children, and who were the Walter, Henry and Eliza recalled by Wright as part of his family at New Year 1831?

It will be remembered that Wright relates that his third wife died shortly after the Reform riots of October 1831, but no announcement of Mrs. Wright's death appears in the Nottingham press for the six months following the riots. The Sneinton parish registers make no mention of her burial at this time, but what they do show is that 'Caroline Rose Wright from Nottingham', aged three years, was buried at Sneinton on November 29th 1831. Could this little daughter's burial be the one remembered by Christopher Norton Wright and associated by him with the child Mary Ann? The reader may now be thoroughly dazed by all this confusion and contradiction, but the census of 1841 helps to clear up one point. The Wright household of Long Row is fully listed there and shows Christopher Norton and Anne (the fourth Mrs. Wright) with their family. This comprised Christopher Norton and Mary, the children of Wright's third wife, together with Henry, aged 9, and Eliza, 8, from the fourth marriage. This explains two of the children said by Wright to be around in early 1831. Walter, though, remains a mystery. Subsequent censuses record the dispersing of the family: two children only were at home in 1851, and by 1861 Christopher Norton and Anne Wright were alone, save for their servant, at Addison Street.

Christopher Norton Wright's long and, by any standards, bewilderingly intricate life ended on August 14th, 1875, and this event was marked by the following paragraph in the Nottingham and Midland Counties Daily Express of August 16th. 'THE LATE MR. C. N. WRIGHT. On Saturday last one of the oldest inhabitants of Nottingham finished a long career of 90 years. We allude to Mr. C. N. Wright, well-known in this town as a bibliopolist and auctioneer. He had at times very rare collections of books and he was a frequent visitor to Newstead Abbey, when that time honoured fabric was in the hands of the late Col. Wildman'. As well as using a fancy word for his occupation, when 'bookseller' would have been perfectly adequate, the paper added a few years to Wright’s age. Strangely enough, no mention of his family was made, and no report of the funeral appeared.

What prompted Christopher Norton Wright to have his first two wives buried at Sneinton is still a puzzle. We know he was married to his first wife at St. Peter's in Nottingham, and one would have expected her funeral to take place there. Perhaps Wright could not bring himself to re-visit St. Peter's on such a sad occasion within a week of his wedding? If her story was true, though, the second Mrs. Wright brings to Sneinton churchyard its only claim to royal patronage. As for 'No hero, I confess', I am driven to the conclusion that it was the work of a muddled old gentleman. The book's editor suggests that Wright’s son decided not to have the memoirs published out of consideration towards the fourth Mrs. Wright, who was still living, but one feels that the book's many errors and omissions must have influenced him to let it remain unread. To me, C. N. Wright comes across as a curiously unlikeable man, but readers of this article may wish to read 'No hero, I confess' and make up their own minds about him.

Wright was undoubtedly a prominent citizen of Nottingham and it is to be hoped that this family headstone remains intact at Sneinton to perplex future generations of local people. For the present we still have much to discover about the life of this enigmatic man.

C.N. WRIGHT'S ADVERTISEMENT in Wright's Directory of 1862. As a Printer Wright was doubtless annoyed to discover that his own advertisement contained an embarrassing misprint.

C.N. WRIGHT'S ADVERTISEMENT in Wright's Directory of 1862. As a Printer Wright was doubtless annoyed to discover that his own advertisement contained an embarrassing misprint.< Previous