< Previous

A NOBLE STRUCTURE :

The story of a local railway monument

By Stephen Best

In December 1979 a new lease of life began for what can be regarded as one of Sneinton’s historic structures. Almost exactly one hundred years after it opened for railway traffic, the bridge spanning the Trent just to the east of the Nottingham Forest football ground became a key part of the urban road network.

The reader may be surprised to find this bridge claimed as a Sneinton feature, especially since the planners have bestowed upon it the name Lady Bay Bridge. For many local people, though, the name Lady Bay Bridge will always be associated with the road bridge which used to lead from Radcliffe Road over the Grantham Canal to Holme Road and Trent Boulevard. The name goes back much further than the canal, however, and the earliest Lady Bay Bridge has been identified as the flood arches which carried the Gamston road over the Bridgford Brook a little to the east of the canal bridge site. When the Midland Railway built its bridge over the Trent in the 1870s, the name generally given to it was a reasonable, if rather confusing one - Trent Bridge. It is worthy of note that the northern end of the bridge was in Sneinton, while its southern end lay, not in West Bridgford, but in a curious detached bit of Nottingham over the river which did not become part of West Bridgford until the passing of the Nottingham City and County Boundaries Act of 1951. It may seem nothing more than an expression of Sneinton loyalism to assert that Sneinton Bridge would have been an appropriate name for the road bridge to bear from 1979, but such a name would have had as valid a claim as Lady Bay Bridge, with the added advantage of having no other recent associations.

Enough of quibbling about the name of the bridge, though. It is time to examine why the Midland Railway constructed the line, and to see what kind of a bridge resulted. Plans were deposited in November 1871 for a route leaving the Nottingham - Lincoln line immediately to the east of London Road, Nottingham. This was to make its way through West Bridgford, Plumtree, Widmerpool and Upper Broughton into Leicestershire, joining at Melton Mowbray the existing line from Leicester to Peterborough. The Midland also obtained powers to build a further line from Manton (between Melton and Peterborough) to join its main line to St. Pancras at Glendon, just north of Kettering. This new route, when completed, would provide a journey from Nottingham to St. Pancras one mile shorter than the old route via Trent and Leicester, and would enable the Midland Railway to tap the iron ore fields of Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire and bring about the development of Corby as a steel town.

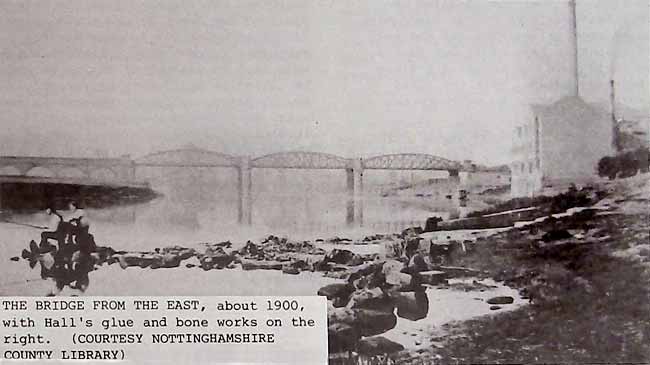

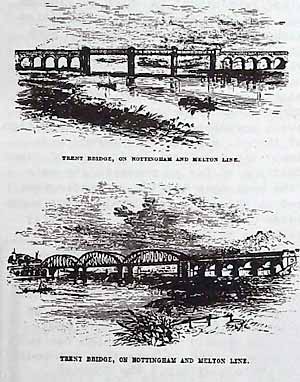

By December 1875 work on the new line was in progress, and in his book 'The Midland Railway, its rise and progress', the Rev. Frederick Smeaton Williams gave some details about the bridge which was about to be built. Living as he did in Forest Road, Nottingham, where he was a lecturer at the Congregational Institute, Mr. Williams did not have far to travel to find out what was going on. He reported that the main spans of the Trent Bridge would carry 'light wrought-iron lattice girders supported by cast iron cylinders which will rest on the bed of the river and be filled in solid with brickwork'. Mr. E. Parry, resident engineer on the site, described how engineers set about constructing a bridge such as this, which, the author promised, would be 'a noble structure'. Parry told F. S. Williams of the task of pumping water from the foundations, and explained how the cylindrical piers would be sunk in the river bed. He also referred to methods then being employed in the building of the Tay Bridge in Scotland. Anyone looking at the first edition of Williams's book will be struck by the fact that the Trent Bridge depicted in an engraving differed appreciably from what was subsequently built, having straight lattice girders spanning the river. By the time that later editions of the book appeared, the illustration of the bridge had been replaced by one more closely resembling the structure actually put up, and the description had been amended so that the 'lattice girders' of the original text had become 'bow string girders' Even in this later view the proportions of the girders are not quite right, but the bridge shown is readily recognisable, with its three elegantly curved main spans and its brick arches on either bank.

By 1879 all was completed, and the Nottingham Journal of 3rd November, in a very inconspicuous paragraph, reported the opening of 'the new and important extension of the Midland Railway' for goods traffic, and the opening of stations at Edwalton, Plumtree, Widmerpool, Old Dalby and Saxelby. The official Board of Trade inspection of the new line took place on 14th January, 1880, under the eagle eye of Major Francis Marindin, Royal Engineers. Apart from his military career, Marindin had achieved eminence in the sporting field, having appeared twice in the F.A. Cup Final as a member of the Royal Engineers teams which were beaten finalists in 1872 and 1874. Aged only 41 in 1880, he had been President of the Football Association since 1874, and would hold this office until 1890. As Colonel Sir Francis Marindin, he was to be Chief Inspecting Officer of Railways from 1895 until 1899. This man of wide interests and talents spent a considerable time examining the bridge, which the Nottingham Daily Express described in some detail 'The river is spanned by three large wrought-iron "bow string" girders, each of a hundred feet. Suitable provision is made on either side of the river, by means of brick arches, for floodwater... The whole of the foundations are carried down to a considerable depth, to the sandstone rock, the primary object being of course to obtain the utmost stability of the structure. The river-piers consist of cast-iron cylinders eight feet in diameter, the interior being filled with blue brickwork, capped by ashlar masonry on which rest the girders. The cylinders referred to descend some four or five feet into the rock at the bed of the river ... As a whole the work is exceedingly creditable to everyone concerned, and fully merited the praise bestowed upon it by the inspector. Indeed, we believe that such really high-class work in every respect is not by any means common....' Major Marindin may have been unstinting in his praise of the bridge, but he took nothing for granted, as the Express report made clear. 'For the purposes of test each span across the river was covered by the heaviest locomotive belonging to the company, representing a much greater strain than can possibly be brought about in the course of traffic... The test was a most crucial one, yet the deflection was most trifling, being no more than three-eights of an inch. When the engines were run over at a high rate of speed there was hardly any perceptible variation in this direction.' This account of heavy engines coupled together running back and forth over the bridge may give an impression of undue fussiness and caution, but such a proceeding was quite usual, and the Railway Inspectorate was leaving nothing to chance - especially not in January 1880. Just seventeen days before the Nottingham - Melton line was inspected, Britain's latest engineering adventure had ended in a nightmare catastrophe. Just four years after Mr. Parry had chatted to F. S. Williams about its construction, the Tay Bridge had collapsed during a storm, taking with it a passenger train and the lives of the seventy-five people on board. Marindin, with other Board of Trade officials, had hurried to the site of the disaster and witnessed the scene of devastation: his meticulous care over the new bridge in Nottingham can well be understood. The local press appeared well content with the new railway, the Nottingham Journal of 15th January summing up the general feeling: 'The line, which, as has been pointed out on previous occasions, will greatly improve the railway communication with Nottingham, and on the Midland system generally, has cost considerably over half a million. It is expected to be opened for passenger traffic very shortly.'

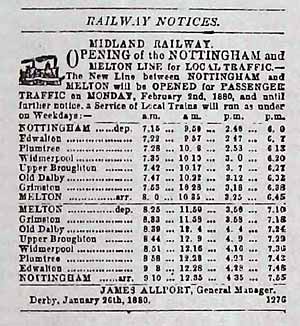

Passenger trains indeed began to run over the newly-inspected route on 1st February, the inaugural time-table providing four stopping trains in each direction on weekdays between Nottingham and Melton. The first train left Nottingham at 7 15 a.m. with the final departure at 6 00 p.m., and a journey time of 45 minutes. The line had of course not been built as a purely local one, and the summer of 1880 saw its first express services. These consisted of five trains each weekday from Bradford, Leeds and Sheffield to St. Pancras, with four in the opposite direction. These new services received a warm welcome from the Nottingham press, which saw in them a distinct advancement in the town's railway status. The Evening Post of 1st June declared that it was 'a minor revolution' in which Nottingham was 'the town most signally benefited.' Although the Post conceded that some London trains would continue to run via Trent and Leicester, its reporter, no doubt with memories of chilly nights spent waiting for late connections, concluded that 'there is every appearance that the new condition of things, when fully matured, will.... imply the practical extinction of Trent Junction so far as concerns the main line passenger traffic of Nottingham, and as this is a consummation for many years devoutly wished, it may fairly be taken to be a matter for general congratulation.' The Nottingham Journal omitted any side swipes at Trent Station, contenting itself with the observation that 'now the new line is open for traffic there will be an additional inducement to make that very favourable journey which can now be accomplished in less than two hours and three quarters.' The Journal observed that improvements to the Midland Station in Nottingham would soon be put in hand, with 'an entirely new suite of refreshment and waiting rooms', and remarked that 'these few facts concerning the new route will serve to show how much the public of Nottingham will be benefited by its opening.' One consequence of the new line which greatly facilitated railway operations was that for the first time trains from the North to St Pancras were able to run through Nottingham without the necessity of reversing.

The organisation of the new through passenger services was in the hands of John Noble, general manager of the Midland Railway, and of Matthew Thompson, the company's chairman. The new expresses, fast for their day, were accorded the popular nickname of 'John Noble Expresses', and by the second half of 1880 were running between London and Nottingham at net speeds of almost 50 miles per hour.

The Nottingham - Melton - Kettering route settled down as an integral part of the M.R network, with freight traffic and through passenger trains its main revenue earners. Local passenger services were never very frequent and it was said that all-stations stopping trains were not heavily promoted because the company needed to keep the line clear for express and goods traffic. By the year 1910, almost the high noon of railway dominance of the country's transport, there were six expresses on weekdays from St. Pancras to Nottingham via Melton, with five fast trains to the capital over the route: the fastest of these took 2¼ hours to cover the 123½ miles.

So for many years the line, and with it the bridge over the Trent, saw intensive use. In addition to local and London-bound passenger services, it carried some through trains from Nottingham to the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway, making it possible for fortunate holidaymakers to travel from Nottingham to, for example, Great Yarmouth, without changing. The second World War saw the first casualty, Edwalton Station closing in 1941, and by the end of the decade the other wayside stations in Nottinghamshire had gone too, Upper Broughton closing in 1948, and Plumtree and Widmerpool in 1949. The Winter 1953 time-table of British Railways showed that there were still six stopping trains to and from Melton on weekdays (with an extra one on Saturdays). There were seven through trains to London, with eight from St. Pancras (ten on Saturdays), but the fastest of these now took 2 hours 22 minutes, rather longer than the journey time of the best trains of 1910 By February 1961 eleven passenger trains in each direction crossed the bridge every weekday, including three through services from St. Pancras, one of which went on to Bradford. The fastest of these crack trains accomplished the journey in 2¼ hours, better than the 1953 time, but no improvement on far-off 1910.

The route's decline thereafter was marked, and the Beeching era, with its ruthless (and to some minds, senseless) weeding-out of duplication of routes, brought about its inevitable end. In April 1966 all through trains were withdrawn with the exception of one in each direction, and this last survivor succumbed on 1st May, 1967. Trains from Sheffield to London were now obliged to reverse in Nottingham, as they had before 1880, and the closure of the line brought with it other causes for regret. (To introduce a personal note, a day spent watching cricket at Trent Bridge has never been the same for this writer since the trains ceased to run behind the houses in Fox Road.) The line out of Nottingham to the south was removed, but the route beyond Edwalton was retained for experimental use by British Rail.

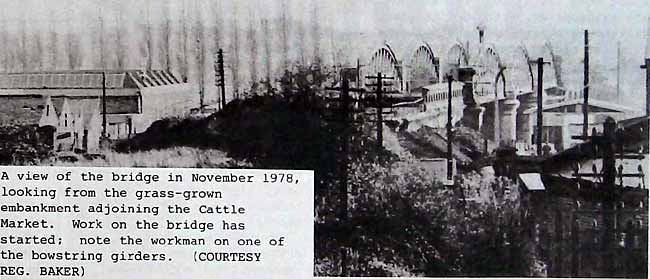

The disused bridge over the Trent slumbered on for some years after closure, its chief use being as an illegal access from Meadow Lane to the City Ground for venturesome football supporters. Then, in 1976, the Preferred Transportation System put forward by the Nottingham and Environs Transportation Study indicated that three road crossings of the Trent at Nottingham were needed; Clifton Bridge, Trent Bridge, and at Lady Bay, using the existing railway bridge. A site for a fourth crossing was to be safeguarded at Colwick. The authorities identified seven steps which would be required to turn the three river spans and the brick arches at either end into a road bridge. It would be necessary to fill the two northerly arches, saddle all the brick arches, and strip the railway deck of ballast and timber. The ironwork would have to be blast-cleaned, repaired and painted, and a reinforced concrete deck would be constructed Finally a steel footway was to be cantilevered off the western side of the bridge, and all the brickwork and masonry cleaned and treated. Samples were taken from the river section of the bridge, and tests showed that the structure was of good quality wrought iron. No accurate records existed of the use made of the bridge over the years by railway traffic, so an estimate was made of this and approved by British Rail. The underwater pier foundations were inspected and found to be sound, while the brick arches were examined to ascertain their loadbearing strength. The wrought iron spans were similarly assessed, and it was concluded that the old railway bridge would be capable of carrying out the function of a road bridge for 120 years, subject to continuous inspection and maintenance.

Work on this project began during September 1978, and on Sunday, 16th December, 1979 the bridge was opened - initially for one-way traffic only - to road vehicles. It was just 100 years and 45 days since the Midland Railway's goods trains had first used it. Opinions may differ as to how successful the bridge has been in its new role, and whether it has been a good thing for Sneinton. It is, however, not the purpose of the present article to go into this question, which may more safely be left for better qualified commentators to discuss.

Oddly enough, both the line and the bridge have been presented to a wider public in recent years. In July 1984 television viewers saw a spectacular high speed crash staged on the experimental section of the line at Old Dalby when it was desired to demonstrate the safety of nuclear waste being conveyed by rail in special flasks. Even more people may have seen the former railway bridge on their screens, though only a small proportion of the audience will have recognised it. This occurred during the final part of the dramatisation of John le Carre's 'Smiley's people', when the Russian defector Karla crossed from East to West. In a scene shot at night-time during the winter of 1981 the old railway bridge made its television debut when Patrick Stewart, as Karla, walked steadily over it from the direction of Meadow Lane.

In conclusion we return to our opening theme. It has been shown that the northern end of the bridge belongs to Sneinton, and that Lady Bay's claims are of comparatively recent date. In the public consciousness, though, the name Lady Bay Bridge is now well established and we are, no doubt, stuck with it. Sneinton has, however, lately lost much of its railway heritage, and we would do well to remember that in the Sneinton/Lady Bay Bridge the area still has an historic railway monument to be proud of.

< Previous