< Previous

THE STEEPLE CLIMBER:

Episodes in the life of Philip Wooton

By Stephen Best

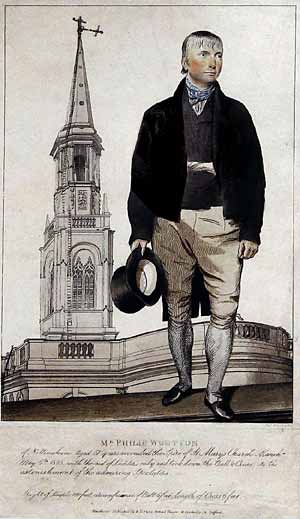

PORTRAIT OF PHILIP WOOTTON published by Parry in Manchester. The caption runs.... 'Mr. Philip Wootton of Nottingham, aged 51 years, ascended the spire of St. Mary's church, Manchester, May 6th, 1823, with the aid of ladders only and took down the ball and cross to the astonishment of the admiring spectators'.

PORTRAIT OF PHILIP WOOTTON published by Parry in Manchester. The caption runs.... 'Mr. Philip Wootton of Nottingham, aged 51 years, ascended the spire of St. Mary's church, Manchester, May 6th, 1823, with the aid of ladders only and took down the ball and cross to the astonishment of the admiring spectators'.(courtesy Manchester Public Libraries: Local Studies Library)

The Nottingham Review of January 13th 1832 reported the death of a man who had made his home in the neighbourhood of Sneinton, but who had left his mark on a much wider area of Nottinghamshire and the surrounding counties. This was Philip Wootton, who died, aged 60, at his house in Pierrepont Street. He was, said the obituary notice, a 'bricklayer and stonemason, but better known by the appellation of "Steeple Climber".' The paper went on to relate that the Wootton family had been noted for generations for the repair of church spires without the use of scaffolding, 'using only in these hazardous undertakings, ladders, hooks and belts'.

Philip Wootton had, according to the Review, made his first ascent of a steeple at the age of four, when his father was engaged in repairing the spire of Repton church in Derbyshire. As a boy he helped his father in restoration work at Grantham, Newark, Lowdham, Holme and Wymeswold churches before beginning to work on his own account in the 1790s. His first independent job was said to have been the repair of the spire and battlements of Cotgrave church in 1794, but a few years earlier than this another member of the family had made a considerable spectacle of himself in Nottingham while engaged in the family business. This was Philip's brother Robert Wootton, who was hired to take down and repair the weathercock on top of the spire of St. Peter's church. Though Robert was not a Sneinton resident, this episode is too good to ignore. The Nottingham Journal of January 24th 1789 related that Wootton, who lived at Kegworth, attached ladders to the steeple at about 11.00 a.m. on January 22nd and 'to the admiration of every beholder, he ascended to the summit and bro't down the vane before two o'clock.... he reascended to the top of the spire, laid his body across it, held up his legs, at the same time spread out his arms, after he had recovered himself, he stood upon the uppermost stave of the ladders, cutting many capers and other gestures for near a quarter of an hour to the great astonishment of a number of spectators....' Nine days later he was ready to re-erect the weather vane; re-climbing the spire he 'carried up a drum, and there beating upon the same for upwards of an hour, when several hundreds of people were assembled in the adjacent streets to view so extraordinary an adventurer'. Other reports had it that Wootton, in addition to his other antics, drank a bottle of ale at the top of the spire and that the public felt that he had overstepped the bounds of good taste. In her diary, Mrs. Abigail Gawthern of Low Pavement recorded the event, noting that 'after removing the weathercock from the spire on January 22nd Mr. Wootton put it up again, fresh gilt, and long ribbons at the tail, January 31st'. In his 'History of Nottingham' published in 1815 John Blackner stated that Robert Wootton died in Nottingham gaol as a debtor, in 1808. In the Nottinghamshire Record Office's copy of Blackner's book I found the following handwritten note at the foot of the relevant page. Of the unhappy steeple-climber it says 'This man's name was Robt. Wootton and was a large horse dealer in partnership with the late Richd. Gilbert, fishmonger, in Parliament Street, and died in prison on account of giving a warrintee of a horse'. A moral there, perhaps, for steeplejacks and fishmongers - stay out of horse trading.

Such a man was Robert Wootton. His younger brother Philip, the hero of this article, may have been less outrageous, but he was, nonetheless, clearly a man to be noticed. We pick up his story in the year 1810, when Philip Wootton was about 38 or 39 years old, to find that the Nottingham press was properly appreciative of one of his recent projects. This was at Gedling, where, according to his obituary in the Nottingham Review, Wootton put on to the spire 'a new neck, ball, and weathercock, and several courses of new stone beneath'. The Nottingham Journal of April 7th 1810 offered a handsome compliment to Wootton and his work: 'It is but common justice to remark, that amidst the various accidents which have lately occurred from neglect, or the natural decay of our churches, there are yet men of science living amongst us, capable of restoring the ravages of time on the beautiful spires of this county, several of which have materially suffered from the very high winds, particularly that of Gedling, which is the most admired by antiquarians, but which is now restored to its former beauty and perfection by the skill of Mr. Philip Wootton, of this town, whose ingenuity and excellent workmanship, in so arduous and hazardous an undertaking, most justly entitle him to the approbation and encouragement of the public'.

Emboldened, perhaps, by this public recognition, Philip Wootton placed an advertisement in the Nottingham Journal three weeks later, on April 28th. 'PHILIP WOOTTON, STEEPLE BUILDER & C., TAKES this Method of informing the Church-wardens of the different Parishes in this Neighbourhood, that he REPAIRS the SPIRES, TOWERS & C. of CHURCHES, in the most substantial and workmanlike Manner, and that he uses no Scaffolding in doing the same. Those who please to employ him, may depend on his giving the utmost satisfaction. All Orders addressed to him (Post paid) in Pump Street, Meadow Platts, Nottingham, will meet with immediate attention'. As well as the information on his mode of working, this advertisement gives us a first indication of whereabouts in Nottingham Philip Wootton lived. Pump Street lay between Colwick Street and Platt Street (now Brook Street and Lower Parliament Street), and Philip Wootton's home must have been very close to where the Sneinton House men's hostel now stands.

Wootton's newspaper obituary, a rich source of information on his career, noted that in 1810 he also repaired the spire at Willoughby-on-the-Wolds. During the following year he carried out work on the churches at Wysall and Widmerpool, while in 1814 he attended to the spire of Gaddesby church in Leicestershire. The next few years saw him working at Mansfield Woodhouse, Linby, and Hucknall in Nottinghamshire, and further afield at Bakewell in Derbyshire. Thanks to Nottingham trades directories published at this time, we know that Philip Wootton did not stray far from the fringes of Sneinton for the remainder of his life. In 1815 he was listed as a 'steeple builder and bricklayer, Sneinton Street', so he must have moved some time after 1810 just round the corner from Pump Street to near where the Sun Valley amusement arcade is today. Nottingham adopted the Watch and Ward Act in 1816, which meant that local citizens were enrolled as a kind of special constable to serve in the case of civil unrest - this was the time of Luddite activity - and the Nottingham Watch and Ward roll for that year includes the name of 'Philip Wootton, bricklayer, 46 Newark Lane'. Newark Lane ran between Sneinton Street and Count Street, its site now lying between the bottom of Hockley and the Ice Stadium. Local directories indicate that Philip Wootton remained in Newark Lane until at least 1825. During his time there he tackled a number of important church repairs including, in 1822, the splendid spire at Ashbourne in Derbyshire. Early in December 1822 a great storm swept across England, and many buildings suffered severe damage. Among these was St. Mary's church, Manchester, where the ball and cross at the top of the spire were blown over to a horizontal position, 'and such was the fear of the inhabitants, that it prevented their attendance at divine worship; in consequence of the great sums demanded to erect scaffolding, it was suffered to remain, until the intrepid Philip Wootton was found, to accomplish the arduous work without scaffolding'. So runs Wootton's obituary notice. For a more immediate reaction we can turn to the newspapers for the week following his Manchester feat. The Nottingham Journal of May 10th 1823 gave a splendidly graphic account of Philip Wootton's daring. 'MANCHESTER, May 6th - On Thursday last, Mr. Wootton (of Nottingham), the person who has contracted to remove the ball and cross from St. Mary's spire, by means of ladders only, arrived in this town, accompanied by his son and an assistant, in order to take advantage of the first favourable weather to carry his wonderful project into effect.... The method by which he contrived to erect ladder upon ladder, in a way sufficiently secure, was as follows:- After having placed one of the longest against the base of the spire, he fastened the top of it to the masonry by new clamps; then, by means of a block and pullies, attached to the upper part of this ladder, his assistants below were enabled to raise another one, whilst Mr. Wootton followed and guided it in the proper direction'. So Philip Wootton went on hoisting ladders until the summit of the spire was neared, and it is clear that reporter and public alike were gripped by the spectacle. 'On Saturday morning, the writer of this arrived as Mr. Wootton was raising the last ladder, by far the most perilous of the whole, and had an opportunity of surveying him through a powerful telescope, and to see the composure and confidence he proceeded with his work, when the least slip would have hurled him to destruction, was truly astonishing. When he had fastened the bottom of this ladder, which was placed against the ball in a nearly perpendicular direction, he had to ascend it, though unfastened at the top; and in this dangerous situation, he contrived to throw a rope twice round the spire and succeeded, at last, in making it perfectly secure; after which, he mounted to the top, stood on the very pinnacle of the spire and pulling off his hat, gave three cheers, which were heartily echoed from the crowds below ....Of the undertaker and his project we can scarcely speak in terms too high and we believe it equals, if not exceeds anything in the records of human daring and enterprise'. Such was the interest aroused in Manchester by Wootton's feat that a local artist named Parry published a print showing the tiny figure of the steeple climber bowing to the crowds below from his precarious perch on the spire. In the foreground is a portrait of Philip Wootton himself, quietly but respectably dressed in knee-breeches, his hat in his hand.

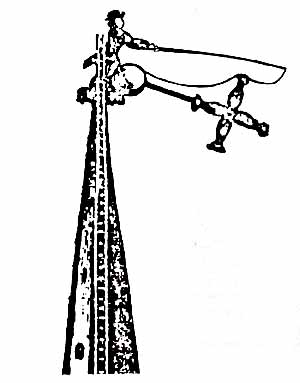

The Manchester press, too, included illustrations with their stories of Wootton's daring. Perhaps the most spirited accompanied an account in 'The Manchester Iris: a literary and scientific miscellany' of May 17th, 1823. This weekly described in great detail how Wootton slipped a noose around the cross to secure it so that it could safely be lowered. A metal bar, however, snapped before Wootton could separate the cross from the ball, and he and his son were obliged to lower them both in one operation: made of sheet copper, the ball weighed 60 lbs. and the cross about 160 lbs.

A delightful engraving depicted Wootton poised at the top of the spire, his hat on his head, attempting in the most ingenious way to lasso the dangling cross.

Although no one knew it at the time, Philip Wootton's 'unspeakably dangerous' enterprise took place exactly half-way through the life of St. Mary's church. Completed in 1756, it was pulled down in 1890 after an existence of only 134 years.

By now a figure enjoying a countrywide reputation, Philip Wootton found plenty of work much closer to home. In the late summer of 1825 he had to travel only a few hundred yards from Newark Lane to attend to the spire of St. Peter's, Nottingham, upon which his brother Robert had so conspicuously acted the fool 36 years earlier. The Nottingham Review related that he 'took down and rebuilt six yards of stone-work from the top.... dressed off the old crockets from the squares and put on a new copper ball, the old weathercock was replaced, after being rebuilt'. There were evidently some celebrations at the conclusion of this job, as the St. Peter's churchwardens' ledgers record the following payments on August 16th, 1825:-

| 'Refreshment to Wootton men | - 5.0 |

| Ringers at finishing the steeple | - 2.6' |

Philip Wootton securing the damaged cross on the spire of St. Mary's, Manchester. From the 'Manchester Iris', May 17th 1823. (Courtesy Manchester Public Libraries: Local Studies Library)

Philip Wootton securing the damaged cross on the spire of St. Mary's, Manchester. From the 'Manchester Iris', May 17th 1823. (Courtesy Manchester Public Libraries: Local Studies Library)Two months later Philip Wootton’s account was settled, the churchwardens paying out £130 on October 29th to 'Wootton for contract for taking down the steeple 16 feet and rebuilding the same with new stone, etc.' A year afterwards Wootton was called in again by the authorities at St. Peter's, the ledger noting that the sum of £10 was paid on October 10th, 1826 to 'Phillip Wootton for pointing the tower at St. Peter's church'.

In his mid-50s Wootton still had work coming in: in 1828 he was engaged to take down and rebuild the spire at Masham in Yorkshire, and, near the end of his life, he repointed and repaired the top of Wollaton church spire. By 1832 Wootton had moved once more, this time to Pierrepont Street. At this date Pierrepont Street ran from Sneinton Road to Water Lane (off Carter Gate), crossing Manvers Street on the way. It is likely that Philip Wootton’s house was towards the western end of Pierrepont Street, on a site now occupied by the City Transport bus garage. This end of Pierrepont Street was in the parish of St. Mary’s and it is the St. Mary’s register which contains an entry recording the burial of Philip Wootton on January 15th 1832.

As has already been mentioned, the January 13th issue of the Nottingham Review gave considerable attention to 'the adventurous labours of Philip Wootton’, remarking that by the 'simple plan he adopted, of rearing ladders one above another, and attached to the steeple with iron dogs, and the use of a small swing ladder, hung by a rope and pulley, he was enabled to pursue his aereal avocation with security to himself, and at an incredible saving of expense to his employers'. The Review went on to emphasise that Wootton, in the course of his career, never had a fall or suffered any physical injury, before ending its biographical notice with a gracious and charming tribute to Philip Wootton. 'Justice to the memory of the subject of this obituary requires that we should also record, that he was a kind hearted, industrious, and honest man'.

So died a valued resident of the Sneinton area: if he is largely forgotten a century and a half later, there remain the spires of Gedling and St. Peter's to remind us of what we owe him.

I thank Mr. David Taylor and the staff of Manchester Public Libraries for information on Wootton's exploit in Manchester, and for permission to reproduce the illustrations.

< Previous