< Previous

'.... supposed to be done on purpose' :

THE DESTRUCTION OF DENISON'S MILL

By Stephen Best

In the early hours of Monday, November 29 1802, residents of Sneinton and the eastern edge of Nottingham were awakened by an angry glare in the night sky, and it was quickly realised that one of the town’s most modern and impressive industrial buildings was on fire. Though Denison's Mill in Pennyfoot Stile was a comparatively new building, it had enjoyed a far from untroubled existence, and the disastrous fire which ended its eleven-year life was by no means the first misfortune it had suffered.

The foundation stone of Robert Denison's cotton mill was laid in June 1791 on a vacant piece of land between what was then Pennyfoot Stile to the north and Poplar Place to the south. In those days the Beck stream ran above ground, forming the boundary between Nottingham and Sneinton, and Denison's Mill was erected on the Nottingham or western bank of the Beck. The site is now part of the Boots complex in Pennyfoot Street, and was for over eighty years between the 1870s and 1960s taken up by St. Philip's church and school. According to John Blackner, the Nottingham historian who wrote some twenty years after the event, the mill was brought into production in October 1792. Robert Denison, himself of Yorkshire extraction, was in partnership with a Leeds merchant named Samuel Hamer Oates, and Denison& Oates's manager, John Need, had been busy advertising in the local press for workers to build and operate the mill. On October 22nd 1791 he placed this notice in the Nottingham Journal: 'WANTED. Several hands for preparing machinery materials, as filers, iron turners, wood turners, clockmakers & c. & c. Also the undermentioned will shortly be wanted, viz. two card masters, two spining masters, a lookerover for the reeling and finishing; an experienced hand in turning and cloathing the cylinders; likewise a number of women, and children for picking, roving, spinning, reeling and the various employments in the business; good wages will be given to such who are skilled in their profession. Apply to Mr. John Need in Coalpit-lane, Nottingham.' Denison & Oates were still seeking labour in September 1792, as the Nottingham Journal of the 8th makes clear. 'COTTON MILL. Wanted: a millwright, who has been used to joiners work, and has been employed in a cotton mill. Also a number of children are immediately wanted. Apply to Mr. John Need, in Pennyfoot-garden, Nottingham.' It will be noticed that the mill manager had by now moved into an office at the mill site. Much of the skilled male labour was required chiefly for the construction of the mill and of the machinery, and once the place was in production a high proportion of the labour force was made up of women and children. A further advertisement in the Nottingham Journal of December 29th 1792 reflects this, with vacancies for three skilled males and numerous unskilled women and children: 'WANTED. Two overlookers; one for the doubling and reeling, and the other a spinning master. Married men, who can produce testimonials of honesty, ability and good conduct, will meet suitable encouragement. Also a number of women and children are wanted. Such persons who wish to remove their families, from country villages or other places, may be treated with, by letter or personal application, as below. Likewise, a millwright, who has been employed in a cotton-mill, and would engage for a short term. Apply to John Need, at the Mill, in Pennyfoot-garden.' It is interesting to read that the owners were glad to attract suitable employees from outside Nottingham; one must hope that not many workers were tempted to move house by the prospect of a rosy future at Denison's Mill.

The new factory was, by all accounts, quite splendid. Based on Atherton's mill in Liverpool, it was an imposing structure of seven storeys, fifteen windows long, with a small pediment and a cupola on the roof. Something of the sort can still be seen in surviving late eighteenth century mills around Cromford and Miller's Dale in Derbyshire. A 30 horse-power Boulton & Watt engine supplied power to 3024 spindles and, according to Blackner, the mill 'gave employment to 300 persons; and was altogether the most handsome and largest manufactory ever erected in Nottingham'. It was recorded that Denison's Mill cost about £15,000 to build, an enormous sum at a time when the Postmaster of Nottingham earned £30 a year and a bricklayer's labourer worked over sixty hours a week for a wage of nine shillings (45 pence).

The year after the opening of the mill saw Britain go to war against the new French Republic. Commercial warfare had characterised Anglo-French relations throughout the eighteenth century but many people prophesied, correctly, that the War would make matters much worse as far as Britain's trade was concerned.

From the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 the British government's supporters had harboured ill-feeling against extreme radical, or 'Jacobin' views, and the landlady of one Nottingham pub received a letter telling her that her home would be burned down if she persisted in giving hospitality to 'Democrats'. Feelings in the town, though, were generally kept under control, those who sympathised with the cause of the French Revolution living in an uneasy peace alongside those who were horrified by it and all that it might imply for Britain. With the outbreak of war, however, many of Nottingham's leading citizens came out into the open in declaring how they saw the situation. On March 2nd, 1793 the Nottingham Journal printed a lengthy anti-War address and petition got up by the Rev. George Walker, minister of High Pavement Chapel, and a man with a consistent record of support for radical and reforming ideas. The address 'To the manufacturers and other inhabitants of the Town and Neighbourhood of Nottingham' pointed out the catastrophic effects that the War would have. 'A Commerce of the highest prosperity, but depending on the most nice and delicate circumstances, must be wholly disarranged by the operations of War. The excellence of our Manufactures is nearly balanced by the high price at which they pass to a foreign market. War will so advance the price, from the increased charge of insurance and the enhanced rate of Freight, that the foreign market will refuse them altogether, or receive them in a very small proportion to the present demand ’ The address went on to argue that England had greatly benefited from peace at home combined with disorder in the rest of Europe, but would by joining the War incur the hostility of almost all European countries, leaving no neutral naval power through which British goods could reach foreign markets. More of the likely economic results of the War were catalogued; unemployment, higher parish rates, and universal disorder and distress. Signed by twenty-six prominent men of Nottingham, the address concluded by stating that it was proposed to offer a petition to the House of Commons asking for peace to be made with France. This petition saw the War bringing great suffering to Britain without any compensatory gain, and causing a rise in food prices and Poor Rates, together with a wider range of taxes. The twenty-six signatories, though they must have appeared as seditious agitators, traitors even, to the most loyal supporters of the government, were in fact solid and respected local citizens, some of them members of the Corporation of Nottingham. They included George Coldham, the town clerk; John Fellows, who was to found a banking house which was eventually merged into Lloyd's Bank, and many merchants and manufacturers of the town, among them Robert Denison.

It has been mentioned that Mr. Walker was minister of High Pavement Chapel, and many of the Whig aidermen and councillors were, like Robert Denison, members of his congregation, or of one of the other nonconformist chapels in Nottingham. The Whig party included many Protestant Dissenters, who were at the time officially ineligible for seats in Parliament, and some followers of a party so dedicated to civil and religious liberty regarded the French Revolution's destruction of the power of the Established Church and of the aristocracy as a blow in the cause of religious and political equality. Nothing could have more appalled the Tories than this opposition to the establishment. Robert Denison was a staunch Whig, who had, years earlier, fallen foul of an equally committed Tory when, in 1777, he had proposed the toast of 'General Washington' at a function at the Exchange Hall. Since this was at the height of the American War of Independence, it is scarcely surprising that Denison’s boldness provoked an ultra-loyalist to attack him physically.

Despite the fact that their stated opposition to the War was purely economic, rather than moral or political, those who had signed the address attracted the anger of Nottingham’s extreme Tories. They had spoken out against the War, so were held to be in favour of the French Revolution, and, by implication likely to welcome something like it in Britain. In the summer of 1793 the houses of some prominent opponents of the French War were damaged by mobs. Even the Mayor, Joseph Oldknow, did not escape, his house in Long Row being pelted with stones. Mr. Oldknow drove off his attackers by firing a blunderbuss at them, killing one of the rioters.

An uneasy winter saw Nottingham into 1794, a year which saw trouble flare up again. The government stated that opposition to the monarchy was gaining ground, and urged loyalists to arm themselves in defence of Church and King. Some Democrats in Nottingham thereupon felt it necessary to resort to 'military discipline' in an attempt to defend themselves against the likely results of what must be regarded as a smear campaign, and so indulged in a sort of military parade, armed with wooden sticks. This naive but hardly threatening performance brought about a speedy escalation of violence, the pro-War faction hiring 'ruffian navigators, then engaged in cutting the canal', to attack citizens known, or believed, to be against the War.

So it was that the disgraceful episode known in Nottingham as 'The Duckings' came about. The victims of the mob were held struggling under pumps, (usually the Exchange pump), while water gushed out over them, or were ducked in the River Leen, the canal, or a ditch near Coalpit Lane, as well as being rolled in the mud, kicked, or beaten up. Then, on July 2nd 1794, the rioters came to Denison's Mill. Whether this was by chance, or whether Denison had been a marked man ever since he signed the petition in 1793 cannot be known for certain, though it does appear that he had expected to be attacked. Two accounts of the assault on the mill vary in important details. The Nottingham Journal, pro-War and anti-Democrat, reported on July 5th that a group of men were set upon for wearing imitations of French cockades in their hats, and fled to Denison’s Mill for shelter. On the refusal of the occupants of the mill to hand over their prey, the 'Royal side' attacked the building, 'and at this time it was, that some shots were fired from the mill, when several people were very badly wounded'. About 9 o'clock, according to the Journal, the attackers 'began to demolish all the fences, gates, & c., round the premises, and made a large fire of them in the mill yard, which soon communicating to the workshops belonging thereto, made a most awful appearance? and, indeed, when the flames issued with so much fury, the greatest care was taken to prevent their extension to the mill and the other surrounding buildings ' The report went on to say that the magistrates ordered out the Light Horse to protect the Mill, 'and thus saved that valuable manufactory from being destroyed'. The workshops and outbuildings which had been set alight were allowed to burn out, eventually doing so at about 1 a.m. The following week's issue of the Journal commended the Mayor, Henry Green, for his 'vigilant and unwearied exertions', before going on to point out that, 'in our hurry of last week's account, we should have stated that the refugees took shelter at the Plough public house, instead of Denison's Mill'. This barefaced admission that its report of July 5th had been incorrect in one of the most important elements of the story seems not to have troubled the paper in the slightest. The Rev. George Walker, who, as might have been expected, took the side of the anti-War faction, had a very different tale to tell. He related that, after a day of pumping and ducking their opponents, the mob set off in search of arms caches on suspected premises, and 'determined on searching the cotton mill of Mr. Denison, at Pennyfoot-stile The windows of the mill were much demolished before young Denison remonstrated with the mob, and told them the consequence of further outrage. Those within the mill were, at last, however, compelled to fire'. According to Mr. Walker, the assailants were driven away from the mill itself, but pulled down a fence and set fire to it, 'from whence, with the most active industry, they communicated the flames to six or seven adjoining tenements, the mill workshops, & c., hoping in the issue to reach the mill itself. After a lapse of four hours and repeated applications to the Mayor, Mr. Denison procured the assistance of the military ' The soldiers arrived just in time to protect the fire engines, whose hoses were being slashed by the mill's attackers. 'It is here seen', concluded the Rev. George Walker, 'that even Mr. Denison's respectability (so well known to the inhabitants of Nottingham) could not protect him from popular outrage, because his conduct ran counter to the stream of popular prejudice'. Despite the Nottingham Journal's praise of the Mayor, it seems certain that, far from helping to calm the situation, Henry Green was out hunting with the mob and encouraging their attacks upon innocent citizens. John Blackner, a vivid historian, but one implacably biased against the Tory Green, recorded his subsequent decline into bankruptcy and death, declaring that 'though he escaped the punishment of man, he was marked out by the finger of heaven', suffering a broken heart brought about by 'want and guilt'.

The attack on Denison's mill was noted in her diary by Mrs. Abigail Gawthern of Low Pavement.

Mrs. Gawthern was a zealous Tory and the daughter of Thomas Frost, who had in far-off 1777 assaulted Robert Denison over the matter of the toast to George Washington. She recorded: 'July. 2. A mob in the Market Place; they went to Mr. Dennison’s cotton mill and set fire to the workshops...'

Denison was understandably shaken by the attack on his premises, and one immediate upshot was that the mill closed and was to remain inactive until 1801. Blackner asserted that the mill had been shut down since March 8th, 1794, owing to the War's ill-effects upon the trade, but later authorities place the closure of the mill after the July riot. In a letter Robert Denison indicated that he was contemplating leaving England for America to escape the current climate of persecution. He did, in the event, send a son away to America, but himself remained in Nottingham in an attempt to obtain compensation for the damage to the mill. In this he was successful, as an official notice in the Nottingham Journal of February 20th 1796 made clear. Inserted by the Corporation, it stated that 'A rate....will immediately be levied upon the inhabitants for a sum of £500 and upwards, being the amount of the damages and costs recovered in the actions brought by Mr. ROBERT DENISON against the Town for the depredations committed in the riots of July, 1794, upon his property'. This advertisement ended on a plaintive note with the hope that no one would hinder the rate collectors in their task of gathering in the £500, as this could only result in the Corporation incurring extra expenses.

Denison's Mill, new though it was, remained idle for about seven years, until production was resumed in June 1801 by Oates, Stevens & Co., who had succeeded the partnership of Denison & Oates. Some three hundred people thus obtained employment, and the mill embarked upon its second period of industrial activity. For a year and a half its luck held: then came the night of November 28/29 1802.

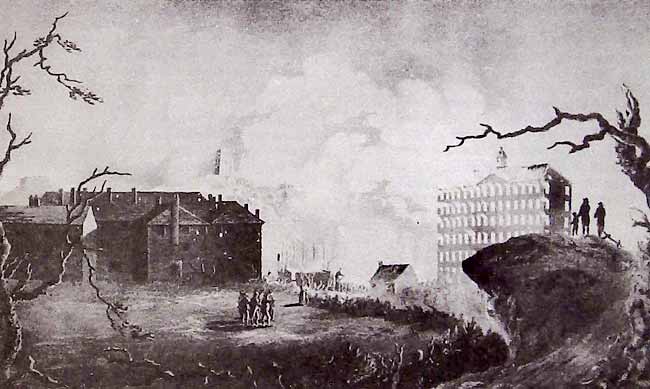

The Mill was discovered to be on fire between one and two in the morning, and the alarm was immediately raised. However, in the words of the Nottingham Journal, 'the fire had gained such a head as to preclude the possibility of arresting its progress; the building by this time being in one entire blaze'. For over two hours the fire-fighters did their best, but 'At half past four o'clock the working of the engines were for a moment suspended, every one viewing it with silent awe, and the fire presenting the appearance of a burning furnace; the glaring reflections of the blaze on the houses and surrounding hills, were the most sublime, at the same time the recurrence of the idea rendered it the most awful imagination could suggest.' There was great anxiety at this time over the possibility that the fire would spread to the houses in nearby Poplar Place, and indeed the flames became so fierce that it seems unlikely that anything could have been done to prevent this. As the Journal reported, though, 'the wind, which before had blown directly on them, fortunately chopped about, and carried the flames in a direction over the meadows '. Then came the end of Denison's Mill. 'About five o'clock the front of this beautiful edifice fell in with a tremendous crash; on which there arose such a volume of smoke and burning embers as exceeds the power of description, and which was carried to an immense distance. The place then exhibited nothing but a smoking ruin, with pieces of blazing timber, beams & c. in the walls that remained standing, till each fell to the bottom in succession, where it continued burning....' The mill burned itself out for almost five days: as Blackner put it, 'the entire machinery with the greater part of the shell were consumed by the devouring element'. Amid all the circumstances of disaster there were compensations; no one died in the fire and £2,000 worth of raw cotton was recovered from the building before the flames reached it. One other consolation would have been less evident at the time: Thomas Barber, the celebrated Nottingham portrait painter, was on the spot to produce a wonderfully vivid and exciting view of the scene, which was a year later engraved and published. Barber showed the flames and smoke leaping from Denison's Mill, lighting up the tower of St. Mary's church in the background, while what Blackner called 'an anxious and sympathising population' looked on.

'VIEW OF THE CONFLAGRATION OF MESSRS DENISON & CO's COTTON MILL ON THE NIGHT OF 28 NOVEMBER 1802'

'VIEW OF THE CONFLAGRATION OF MESSRS DENISON & CO's COTTON MILL ON THE NIGHT OF 28 NOVEMBER 1802'Aquatint after a painting by Thomas Barber. (Viewpoint: Sneinton Hermitage).

The Nottingham Journal reported that the mill was insured for about £10,000 with the Sun and Royal Exchange fire offices, 'this being about two-thirds of the real loss'. There was evidently a great deal of speculation in Nottingham as to how the fire started. 'Conjecture', said the Journal, 'has hatched many absurd theories, but from every enquiry, it does not appear that the report of its being the work of some diabolical incendiary, is deserving the least attention'. Up in Low Pavement Abigail Gawthern made an entry in her diary: 'This morning at 3 o'clock we were waked by the cry of fire; it was Mr. Dennison's cotton mill, a dreadful conflagration though a grand sight it was entirely burnt down; supposed to be done on purpose'. Did Mrs. Gawthern, one wonders, gain a grim satisfaction from the passing of Denison's Mill? Certainly she had nothing in common politically with Robert Denison and would not have forgotten how, a quarter of a century earlier, he had enraged her father by his pro-American views. Perhaps Abigail Gawthern would have been only too ready to believe that the mill's destruction was caused by arson, but the Nottingham Journal report makes it clear that she was not the only citizen of the town to hold this opinion. So utterly ruined was the mill that it was never rebuilt: the site was cleared and turned into gardens, while the three hundred workers had to look elsewhere for employment.

But what of Robert Denison? This man of strong convictions and resolute actions continued to worship at High Pavement Chapel, where he was remembered years afterwards as an old gentleman with a pigtail who attended service in a green dress coat. His reforming zeal never abated, and he remained an opponent of the War against France. In December 1812 he made a stirring speech at a public meeting held to discuss the sending of a petition to the Prince Regent and to Parliament calling for peace and the revival of commerce. Denison, described by the radical Nottingham Review as 'the long tried friend of his country, and the unwearied exposer of public peculators', spoke of the 'prodigality of the blood and treasure' with which the War had been conducted, and made it clear that though he had long supported the Whigs, he now felt that neither of the main political parties showed any serious desire to restore peace. With a real sense of the dramatic he held up in one hand a nine-ounce loaf, the penny loaf of peacetime, comparing it with 'the consumptive starvling' penny loaf on sale after nineteen years of war, which weighed just over three ounces. This demonstration, according to the Review, caused 'great sensation and applause'. True to his principles, Robert Denison also deplored the war against 'our American brethren'. Four years later, and past his 70th birthday, Denison was still active, signing yet another petition for the reduction of the standing army, the ending of all sinecures and unmerited pensions, and for 'full, fair and equal representation in the Commons'.

Robert Denison died, aged 81, at his home at Daybrook on July 9th 1826, the day after the death of his youngest son Alfred, who was only 38. The Nottingham Journal, never a friend of Denison, marked his death with a curt notice, but the Review described him as 'ever the consistent supporter of civil and religious liberty, and the undeviating and ardent friend of Parliamentary Reform'. The Review obituary recalled Denison's signing of the anti-War petition of 1793, adding, 'happy would it have been for England, for Europe, and the world, had that petition been attended to....' The paper went on to reveal that during the riots in 1794 'Mr. Denison was obliged to carry a brace of loaded pistols, for the preservation of his life', but that when the people of- Nottingham had, a few years afterwards, endured 'the horrors of war', feelings changed and Robert Denison 'lived to see the principles which he had espoused obtain the ascendancy in his native town'.

A visit to Pennyfoot Street today reveals a landscape changed out of all recognition from the time when Denison's Mill stood on its south side. The open country between Nottingham and Sneinton has long since disappeared, and the buildings in Pennyfoot Street have themselves changed several times. You can still, though, look up the

hill to Sneinton Church, where, in the shadow of one of its predecessors, the villagers of Sneinton gathered on that November night in 1802 to witness the final destruction of one of Nottingham's most important industrial buildings.

The fire at Denison's Mill was not the only serious factory blaze at Sneinton during the nineteenth century. As we shall read in the next Sneinton Magazine, the reign of Queen Victoria was to see two more, one of them the costliest fire that Nottingham could remember.

AMONG THE SOURCES consulted for this article are the relevant issues of the Nottingham Journal and Nottingham Review. I should also like to acknowledge my debt to the following books:- S.D. Chapman, The early factory masters (David & Charles 1967): A. Henstock (ed.), The diary of Abigail Gawthern of Nottingham 1751-1810 (Thoroton Society 1980): M.I. Thomis, Politics and society in Nottingham 1785-1835 (Blackwell 1969); My thanks also go to the staff of Nottinghamshire Record Office and Nottingham University Library and Department of Manuscripts, and to Abigail Gawthern for my title.

ILLUSTRATION BY COURTESY OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY LIBRARY, LOCAL STUDIES LIBRARY.

< Previous