< Previous

'LET THEM GO TO NETHERFIELD' :

Thoughts of a guided walk leader

By Stephen Best

For the average participant, a guided walk of Sneinton is an agreeable way of spending a couple of hours or so. If the walk passes off smoothly (as incredibly most of them do), it is because a number of Sneinton Environmental Society members have, for much longer than two hours, been doing their best to give an impression of well-oiled machinery whirring effortlessly away in the background. Such a statement is, admittedly, likely to be greeted with hollow laughter by the guided walks co-ordinator, by those who provide refreshments and souvenirs, by keyholders and by the selfless troglodytes who pass their afternoon in the bowels of the Hermitage cave enumerating to visitors its features of interest. The guide, however, is acutely aware that he is very much the front man, who, while receiving most of the public's thanks, can no more claim credit for the total success of the walk than a newsreader can for the overall quality of a television bulletin.

Leading a walk, though, does have its pitfalls and responsibilities as well as its rewards, and for this guide the forthcoming walk begins to cast its insistent shadow in the middle of the preceding week.

The date will have been in my diary for months, but about Tuesday I look anxiously at the weather predictions for the weekend. What are the forecasters promising? Are they to be believed? In the event of incessant rain will anybody turn up? Eventually deciding that even the Environmental Society has imperfect control over the weather, I try to remember whether I have been told that there are any weddings arranged for Sneinton church on Saturday afternoon, necessitating a change of timing and route. Although we see the interior of the church at the very end of the walk, we do usually visit the churchyard early on, and no one’s wedding photographs are likely to be enhanced by a background crowd of extras in anoraks and gumboots.

Friday evening is usually occupied in glancing through my notes to make sure that when the time comes I shall be able to find something intelligible to say about George Green's scientific work, and in offering up the silent prayer that nobody will ask me anything about his contribution to contemporary physics. This exercise concludes with the reflection that if I don't know it by now, I never shall, and that, with luck, I will know more about Sneinton than the participants in the walk, and thus be capable of emitting an air of calm omniscience. It is, perhaps, worth pointing out that such an impression of knowing everything is largely the result of doing the walk by yourself several times, noting down what you want to talk about and what visitors are likely to ask about, and then committing it all to memory: inspiration plays little part in the process. Regrettably, folk memories and handed-down stories, so cherished and lovingly polished with every re-telling in Sneinton, are frequently incorrect or unproven, so this guide sternly relegates them to the category of legend, sticking to the facts and only grudgingly admitting the tall stories into the walk commentary as sidelights on the truth. I sometimes suspect that the walks conducted by my fellow-guides may be more fun than mine, and that, untrammelled by the constraints of proof, some extremely racy Sneinton tales are delivered to delighted visitors. Short of my going round on other people’s walks in disguise, though, this must remain no more than a surmise. It is, however, fair to say that to get a truly rounded picture of Sneinton, the dedicated walk attender should sample at least one walk with each guide.

With the arrival of Saturday lunchtime, I need to satisfy myself that the secretary of the Society is on hand to count heads and shepherd the party across Sneinton's busy roads. A glance inside The Fox confirms the presence of Brian Jackson, secure in the immortality conferred upon him by John Sheffield in his kindly but searching account of a Sneinton guided walk from the customer's viewpoint. (See Sneinton Magazine No. 24.) Brian hurries me towards Notintone Place, where members of the walk are gathering. Frowning at a thinnish attendance, he will mutter, 'Not many here today', a judgment varied only by his 'Good God, look at that crowd', if numbers are high. There remains the ritual wait for the latecomers who, according to Brian, will be on the bus arriving just after 2.30, and then I move to the doorstep of the house next door to William Booth’s birthplace, and wish the visitors good afternoon.

Here is a moment of truth. To begin with, the numbers: I have had as few as eight (on a Cup Final afternoon) and as many as eighty-two. This latter was a most flattering attendance even though, as the afternoon progressed, one felt increasingly like the Pied Piper, leading this variegated crocodile of humanity through the streets of Sneinton. The most vivid recollection of this particular walk concerns our passage of Lees Hill Street. As our procession passed his front door, a genial gentleman in a blue vest was putting an empty milk bottle on his doorstep. With barely a hint of a double-take he called out, 'How many sugars do you all take?' A Sneinton moment to cherish. Then one tends to scan the party to see just who has come along. I have had colleagues from work sneak in at the back, and even my boss has promised (or threatened) to turn up one day. Usually, though, the visitors fall into one of about four broad groups. First there comes a significant number of people, often in or past middle age, who enjoy the walk experience and make a point of going on as many guided walks as there are available. I think that these are the hardiest of our visitors, being willing to turn out in the vilest weather, and putting younger people, including fainthearted guides, to shame. Then there are those who may have moved recently into the Sneinton area, and want to find out more about their neighbourhood. Others tell us that their parents or grandparents grew up in Sneinton, and that they have seized the opportunity of visiting the scene of family anecdote or legend. There remain those who have heard the walk advertised on local radio and have come on impulse, together with people with a special reason for attending the walk: friends of the guide perhaps, or local teachers seeking background information for project work. As for younger visitors, it is noticeable that unaccompanied children and those who would once have been called teenagers seldom patronise the guided walks, and that when they do, the Hermitage cave is the great attraction. Finally, there are the media. At least one radio reporter has trudged round Sneinton with a tape recorder and, as already related, a writer has participated in a walk in search of copy for an article. As I write, though, it occurs to me that I may be guilty of misrepresenting John Sheffield's motive for attending a guided walk, and that he may have visited Sneinton with no intention of ever describing the experience, but in the afterglow of two hours under the spell of Tom Huggon and Brian Jackson felt impelled to set down his impressions.

Still perched on the Notintone Place doorstep, I tell the visitors my name, welcoming them to Sneinton on the Society's behalf, a thumbnail history of Sneinton follows, with a brief account of Notintone Place and General Booth, and it is explained that on guided walks we concentrate on places normally inaccessible to the public, which is why the museums at William Booth's birthplace and the Windmill, though highly recommended to everybody, do not form part of our itinerary. As we move off, a conversation is usually struck up with two or three of the party. Twice I have been asked if I am the Stephen Best heard on local radio, but any flickering satisfaction felt at this enquiry has been quickly doused by my questioners' next comments. On my admission that mine probably was the voice which had been heard I was told, 'I was expecting an older person’, and 'Oh, I though you'd be smaller'.

In the churchyard George Green's grave is, of course, the magnet, but there are plenty of other talking points, like the gravestone of the first three wives of C. N. Wright, stationer and bookseller of Long Row. This stone relates the lamentable story of Mary Ann, the first Mrs. Wright, whose marriage and death occurred within two days in 1813. Christopher Norton Wright’s amnesiac memoirs, published only in recent years, may well form the most unreliable volume of autobiography ever written. Elsewhere in the churchyard a visitor once caused a ripple of rather superior laughter by asking whether it was not true that General Wolfe lay buried here. It was pleasant to be able to stop the mirth by confirming that this was so, even if the man in question was not the hero of Quebec, but General Wolfe, beerhouse keeper of Island Street.

From the churchyard, a leisurely progress down Sneinton Hollows and into the Hermitage allows me to point out some of Sneinton's oldest houses and invite visitors to admire my favourite features of the area's late Victorian and Edwardian houses, the carved heads on the doorways and the magnificent ceramic tiles in many of the porches. I told visitors on a recent walk that we would pause at the corner of Sneinton Hollows and Castle Street, a spot which exemplified the new spirit of Sneinton, with sensitive restoration and local pride going hand-in-hand to improve the environment. When we arrived there, the centre of the stage, as it were, was commanded by a decaying and malodorous sofa attended by a swarm of bluebottles, dumped on the very corner from which we were to view the reviving townscape.

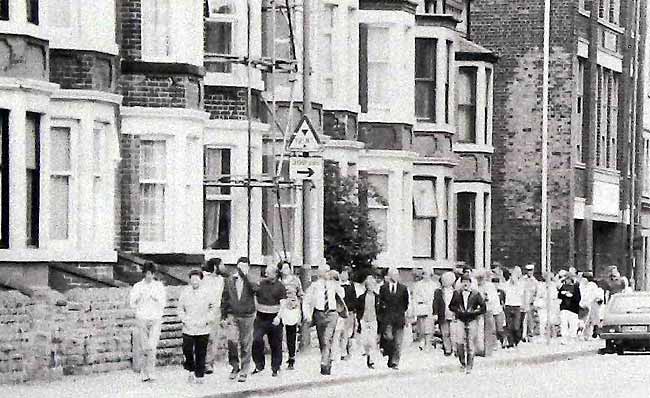

EN ROUTE FOR THE HERMITAGE CAVE and refreshments! Photo: Stephen Best.

EN ROUTE FOR THE HERMITAGE CAVE and refreshments! Photo: Stephen Best.The Hermitage cave makes a natural break in the walk. Those who wish to examine its interior do so while the remainder of the party are encouraged- to buy Sneinton souvenirs, guidebooks, magazines and refreshments. The Hermitage is a great place for speculation and legend: we are not sure what the cave rented by the Society was used for, though one expert has said that its layout includes some of the features of caves in which malting was carried out. The scoop well at the deepest part of the cave has led locals and visitors alike to speak of some mythical great lake beneath Sneinton, while the scanty remains of rock dwellings or out-houses have been identified with reckless confidence as grandma's bedroom. Not the least skilful part of a guide's job is to dispose of such fancies without ruffling anyone’s feelings.

The second half of the walk usually describes a wide arc from the top of Lees Hill Footway to the windmill, a route which takes one past not only some of Sneinton's oldest and most interesting buildings, but also a number of unhappy and ill-judged 'improvements'. Like the other guides I try to explain why unsuitable replacement windows, incongruous stone-cladding and the like detract from the character of Sneinton, and to say something about the controls now in force in the Conservation Area which are designed to prevent such excesses in future. Here I must admit to a distinct lack of punch, of dynamism, in the delivery of my walk commentary when compared to others. The Chairman of the Sneinton Environmental Society, for instance, has no compunction in standing, with his party, close to one such 'improved' house and announcing that here is a particularly tasteless example of bad modernisation. Lacking Dave Ablitt's outer garment of righteous conviction, I tend to cower on a nearby street comer and request our visitors to note and deplore the offending house when we pass it. Even this discreet approach is not invariably successful. Fellow members of the Society, subtle humorists all of them, may call out, 'Is this the house you were on about?', as their cringing guide tiptoes past the blighted dwelling in question; while on one walk I was taken to task by a man who rounded on me with the words, 'Why shouldn't owners alter their houses as they want to? If people want to look at old terrace houses, let them go to Netherfield!' Though we parted on civil terms, I did not feel that I and this particular visitor were ever quite on each other’s wavelength.

For some people the Windmill marks the end of the walk. Although the mill itself is not open on Saturdays they may choose to sample the delights of the George Green Science Museum, and they may, in addition, have had enough walking for one afternoon. As mentioned earlier, though, I like to finish the walks I lead with a visit to Sneinton church. Experience suggests that those visitors who do want to see inside the church enjoy making a leisurely inspection of it, longer, in fact, than can comfortably be spared during the course of a walk. By opening up the church after the other places have been visited, we are not keeping anyone else waiting for us. Here a recently departed and much-loved Sneinton character must be saluted. The Reverend John Tyson has always been a good friend to the Environmental Society, making his vicarage lawn available for garden parties and gladly allowing the church to be made an integral feature of our guided walks and other activities. The Society, for its part, has regarded the church and churchyard as a natural heart of the Conservation Area, and has been the initiator of a recent scheme for tidying up the churchyard, removing litter and debris and repairing some of the gravestones.

One afternoon in the church I had extolled the splendours of the mediaeval choir stalls, acquired by Sneinton church in the late 1840s when they were turfed out of St. Mary’s, Nottingham. I mentioned that there was an absurd local tale to the effect that the stalls had been purchased on Sneinton Market. (The market had in fact not been in existence at the time.) The visitors had dutifully admired the woodwork and other points of interest in the church, and were preparing to go home when the Vicar looked in. 'I hope you've enjoyed the choir stalls', he remarked. 'They were bought at Sneinton Market for ten shillings.' To this day, I think, John Tyson must wonder why thirty people fell about with laughter at this innocent observation. On another occasion, having taken care to steer clear of a wedding, we had brought a walk to its conclusion at the church after all the wedding guests had left. The Vicar was still in church, and in his usual unassuming way tacked himself on to the walk party to listen to the guide's spiel. All those present were squeezed into the chancel, where once again the carvings on the stalls were in the spotlight. I remember that on my pointing out my favourite, a mermaid with comb and looking-glass in hand, there was a bit of a scuffle in the crowd as a cassock-clad figure appeared at my side. John Tyson scrutinised the mermaid, looked at me, and turned to the visitors with the disarming announcement that in twenty-six years at Sneinton he had never noticed the figure, and that it had taken a guided walk to open his eyes. A typically generous Tysonism: we look forward to going on one of his guided tours of Carburton and Clumber Park.

My final walk of 1987 brought me two unexpected moments. Prominent among those assembled at Notintone Place was a gentleman sporting a kind of baseball cap bearing the legend 'Arizona'. Enquiries elicited the information that he had not come quite that far to attend the walk, being in fact a resident of New Jersey. Half way down Sneinton Hollows he provided me with my first surprise by telling me that I reminded him of President Reagan. He went on to explain that some eccentricity of speech, rather than any stated view of the world on my part, had brought the President to mind, but I could tell that he was disappointed by my muted response to this illustrious comparison. A certain amount of genial banter passed between us during the remainder of the walk until, at its end, he once more left me bereft of speech, when, with much circumspection and gravity, he tipped me a pound.

The guided walks are finished now until the spring, though one year Dave Ablitt's dream of a Boxing Day walk may come off. Soon though, we shall be at it again, trying to prove that a Saturday afternoon in Sneinton is time well spent.

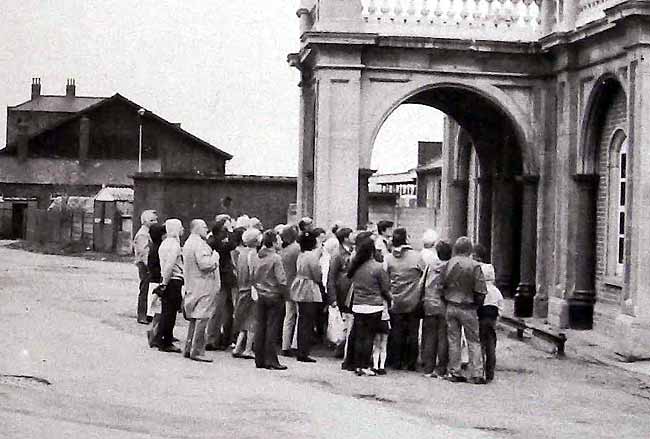

ANOTHER ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIETY WALK. This time, around Sneinton's historic Railway Land. Photo: Stephen Best

ANOTHER ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIETY WALK. This time, around Sneinton's historic Railway Land. Photo: Stephen Best< Previous