< Previous

SOLD FOR A SONG?

The choirstalls of St Stephens

By Stephen Best

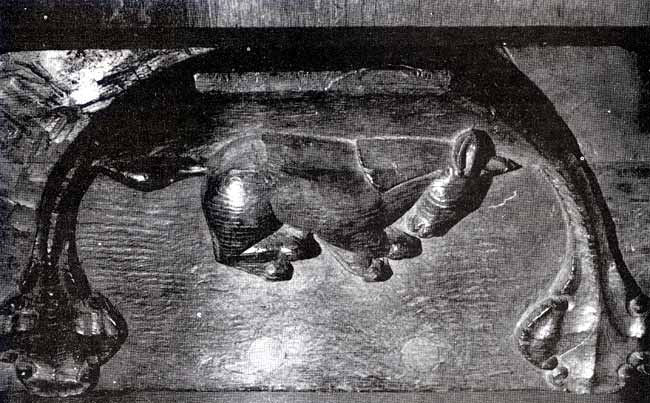

CHOIRSTALL DETAIL. A carved donkey.

CHOIRSTALL DETAIL. A carved donkey.Mention has been made from time to time in 'Sneinton Magazine' of the medieval choir stalls of Sneinton church. Visitors have shown considerable interest in the carvings on the stalls, and have been told of the various legends surrounding their arrival at Sneinton. A recent chance discovery in the 'Nottingham Journal' of July 2nd, 1847 has thrown extra light on the disposal and acquisition of the choir stalls, showing that they were even then a topic of public debate. The relevant news item in the 'Journal' runs as follows 'ST. MARY'S CHURCH - We have no doubt that the fate of the fine old oak stalls which formerly belonged to this church, and which were probably coeval with the date of that venerable structure, must have been the subject of much anxiety to every ecclesiologist in the neighbourhood. It will be remembered that they were taken, or rather smashed down in the most

wanton manner; and after lying about for some months, without the slightest care being taken of them, they disappeared - having, as the rumour stated, being offered for sale at all the curiosity shops in Wardour Street, and at last 'disposed of for £10 - a sum infinitely below their real value. It is some consolation, however, to know that they have fallen into good hands. They have been skilfully restored by our townsman, Mr. Stokes, and erected in the chancel of St. Stephen’s Church, Sneinton, for the use of the choir; and though we would have much rather seen them where they were, and now ought to be (for we cannot imagine the shadow of a reason for replacing them at St. Mary's, with the flimsy deal pews that now fill the chancel), we are rejoiced to find that they will at least escape destruction.'

All of this goes to prove that the choir stalls came to Sneinton rather earlier than has hitherto been suggested. The usually accepted version of events is that the Sneinton choirmaster and Nottingham banker William Henry Wilcockson bought the choir stalls (or a portion of them) thrown out by St. Mary's in 1848 at the restoration and refurnishing of that church. Some writers have asserted that Wilcockson purchased them in Nottingham Market, others that he saw the seats lying about in St. Mary's churchyard and acquired them there and then. A third story has Wilcockson buying the choir stalls in Sneinton Market. The cost of the purchase has been stated to be as little as ten shillings, and as much as £30, but the 'Journal' report makes it likely that £10 was nearer the mark. (We shall, however, be seeing evidence that supports the ten shilling tale.) It is odd that the newspaper makes no reference to Mr. Wilkinson’s part in the affair, though mentioning the role played by 'our townsman Mr. Stokes'. An examination of contemporary Nottingham trade directories suggests that this gentleman must have been George Stokes, joiner and cabinet maker of Upper Parliament Street. It is intriguing that the 'Journal' reports a rumour that the stalls had been offered to London dealers. One wonders whether this was true, and if so, whether the Wardour Street shops were not interested, or were simply outbid by Wilcockson.

A second press story concerning the choir stalls appeared in 1847. This was in the December issue of the influential periodical 'The Ecclesiologist', which related that 'some very curiously carved and valuable stalls have been purchased, which are now undergoing the most careful restoration, and will be placed in the chancel on either side'. Whether the 'Nottingham Journal' was premature in its announcement, or 'The Ecclesiologist' a bit tardy in its report, we cannot tell: one feels, though, that the local paper was more likely to have known what was going on in Sneinton, while 'The Ecclesiologist' could have heard about it later. At all events, it is clear that the woodwork was acquired for Sneinton church in 1847, and that the Sneinton Market theory can be knocked on the head once and for all, the market not being held until nearly six years after the arrival of the choir stalls at Sneinton. Both the 'Nottingham Journal' and 'The Ecclesiologist' made it clear that the stalls as bought had to be restored, and most other accounts refer to this. Robert Mellors, in his 'Sneinton, then and now', states that as much as £30 to £40 had to be expended on this repair work, a sum which indicates that much had to be done to make the seats serviceable. It must be borne in mind that, as they appear today, the choir stalls incorporate a good deal of Victorian woodwork. It is also evident that what came to Sneinton must have been only a part of what had existed in the chancel of St. Mary's church: one can only conjecture what was lost.

It has already been observed that the newspaper report of July 2nd, 1847 omitted any mention of W. H. Wilcockson's involvement, and it is curious that his purchase of the choir stalls also escaped notice in press accounts of Wilcockson's death and funeral in November 1887. The 'Evening Post at that time did, however, credit Mr. Wilcockson with having started a surpliced choir at Sneinton church in 1847. One is tempted to think that, having organised a surpliced choir, he was determined that it should have somewhere appropriate to sit. Belated acknowledgement came in 1900 when a miniature oil painting of William Henry Wilcockson at the age of eight was included in an exhibition put on by the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire. The miniature was lent by Wilcockson's son Bernard, and it must be presumed that the accompanying biographical note was contributed by him too. This stated that, 'when the stalls were removed from St. Mary's Choir, and placed in the churchyard, he bought them and presented them to Sneinton church'. Further mention of Wilcockson’s benefaction appeared in the July 1909 number of Phillimore's 'County Pedigrees'. In the section dealing with the Wilcockson family, William Henry is described as having purchased the chancel stalls from St. Mary's 'at the restoration of 1848'. The account also includes the only portrait of Wilcockson known to this writer, apart from the boyhood miniature whose present whereabouts are a total mystery. The 'County Pedigrees' portrait, far from depicting a little boy, shows William Henry Wilcockson as a plump faced elderly gentleman with generous whiskers.

Added, and rather startling, confirmation of Wilcockson's rescue of the choir stalls came in a paragraph in the 'Nottingham Journal' of January 24th, 1944, with what purported to be an eyewitness account of their acquisition. A Mr. E. Lloyd Armstrong of Bournemouth claimed that he and his brother had been with Wilcockson when the latter saw the stalls on a junk heap in St. Mary's churchyard, about to be burnt as rubbish. Mr. Armstrong asserted that 'the workmen were glad to be rid of the stalls for ten shillings'. The date was given as 1848, which we now know must be incorrect, and the story does not make it clear whether Mr. Armstrong was still alive in 1944, or whether a family legend had been relayed to the 'Journal'. One suspects that even if he had survived to such a great age, his memory might by then have become less than faultless, especially in the matter of the payment for the choir stalls. Clearly further investigation into Mr. E. Lloyd Armstrong is needed, but for the time being this is the best direct evidence we have, and, if true, seems to dispose of the Wardour Street rumours. Yet one is still unconvinced. It does seem very odd that, if Nottingham people were as concerned about the fate of the St. Mary's choir stalls as the 1847 'Journal' report suggests, workmen on the site were at liberty to sell them for ten shillings, even to someone as respectable as the Sneinton choirmaster and organist. We may never know exactly what happened.

Since Sneinton has much to thank him for, a brief outline of W. H. Wilcockson's life may not come amiss here. He was born in January 1816, the youngest son of John Girton Wilcockson, apothecary of Long Row, and his wife Lucy Pinkney. As a boy he suffered a very serious injury to his right knee, falling and cutting it so badly that he had to take to his bed for three years. Cured by the Nottingham surgeon Alexander Manson, Wilcockson, after 'a succession of accidents in later life', was eventually to lose his right leg. After an early architectural training he became in 1834 a junior clerk at the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Bank. For several years he was manager of the bank's Worksop branch, returning to Nottingham in 1857 as general manager, a post he held until shortly before his death. On New Year's Eve 1886 he retired from active management at the bank, and was appointed joint general manager. He was given a seat on the board, together with a gratuity of 500 guineas from the bank's shareholders. Mr. Wilcockson did not live long to enjoy his retirement, dying at his home in The Park on November 22nd, 1887. His funeral, which took place at Sneinton on the 24th, was attended by many of the most prominent pillars of Nottingham's business and professional life. William Henry Wilcockson was buried in Sneinton churchyard, close by the east wall of the church. His grave has, unfortunately, lost its inscription in recent years. There is, however, a window in the Lady Chapel in his memory, with a figure of the prophet Nehemiah, and an inscription stating that he 'rescued the mediaeval choir stalls from destruction and gave them to this church about 1848'.

A GROTESQUE FACE ON ONE OF THE STALLENDS.

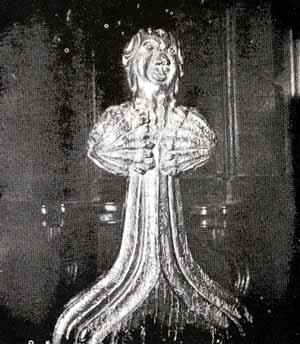

A GROTESQUE FACE ON ONE OF THE STALLENDS.What of the choir stalls themselves? Even after their extensive repairs at the hands of Mr. Stokes in 1847, they were to undergo a further alteration before assuming their present appearance. When the chancel of Sneinton church was rebuilt in 1909, the stalls were modified for use as return stalls, backing on to the screen as well as on to the side walls of the chancel. For many visitors the most enjoyable medieval carvings are those under the tip-up seats in the stalls. These carvings make a sort of ledge or shelf which, when the seat was turned up, provided welcome support for the occupant during lengthy periods of standing: for this reason they were known as misericords, from the Latin word for 'mercy'. Among the eight examples at Sneinton are a chained monkey holding a cup; a rat blowing a horn, riding on the back of a hound; a cat-like creature with its prey in its mouth; a lion, and a wonderful lolloping donkey. The bench ends include carvings of grotesque faces, and dolphin-like beings with human and monkey heads. The arm rests have carved Tudor roses and faces, while the front panels are similarly decorated. The panelling behind the seats on the north side incorporates a horse, a pair of dragons and a delightful mermaid combing her hair.

Reading about the Sneinton choir stalls is, however, no real substitute for looking at them, and every visitor will find something to relish. The fact that much of the woodwork is decent, unobtrusive nineteenth-century copying of the original style should not worry us too much. What remains of the medieval stalls ejected from St. Mary's over 140 years ago is important enough to uphold Sneinton's claim that it possesses the finest church woodcarving in the City of Nottingham. That the choir stalls survive at all is an abiding testimony to the perceptiveness and generosity of William Henry Wilcockson: if, just over a century after his death, this short article helps dispel the obscurity into which he has vanished, then the present writer will be well content.

CARVINGS OF MERMAID AND HORSE ON THE BACK PANELS OF THE CHOIR STALLS.

CARVINGS OF MERMAID AND HORSE ON THE BACK PANELS OF THE CHOIR STALLS.< Previous