< Previous

“A SIGHT AWFULLY GRAND” :

Sneinton’s Great Fire of 1874

By Stephen Best

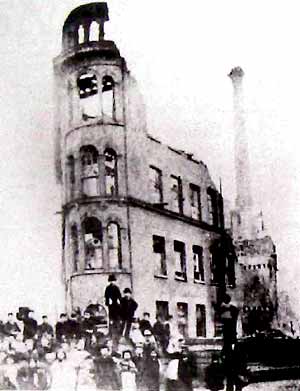

THE SCENE OF DEVASTATION after the fire: the precarious state of the walls can clearly be seen. Cameras were rarer in 1874 than they are nowadays, and the eyes of every bystander are on the photographer.

THE SCENE OF DEVASTATION after the fire: the precarious state of the walls can clearly be seen. Cameras were rarer in 1874 than they are nowadays, and the eyes of every bystander are on the photographer.Past issues of 'Sneinton Magazine' have contained accounts of the disastrous fires which destroyed Denison's mill in Pennyfoot Stile and Hudson & Bottoms lace-dressing establishment in Walker Street. Forty-five years after the latter blaze there occurred the third of Sneinton's great factory fires : this struck at a business of nationwide reputation, and was believed at the time to be the costliest fire yet experienced in Nottingham.

For some generations Sneinton Manor was lived in by the Morley family, and it was here that the brothers John and Richard Morley were born, John in 1768 and Richard seven years later. Their father combined the occupations of farmer and hosiery worker, a duality of interests far from uncommon at the time. In due course John and Richard entered the hosiery trade with premises in Greyhound Yard. Hosiery making was predominantly a cottage industry, with the stockings being made in the homes of the knitters: the Greyhound Yard building acted as a collection and storage centre and as offices.

It should perhaps be explained that, at the time of the founding of the business, the initials 'I' and 'J' were written in identical fashion, and although the partners were John and Richard Morley, the title of the firm was variously understood to be J & R. and R. Morley. In order to put an end to uncertainty, the business eventually adopted the style I.& R.Morley officially.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century John Morley moved to London, where he set up an office and warehouse to organise the sale of Nottinghamshire-made goods. Richard looked after the Nottingham end of the business, at first in the Greyhound Yard building, but later in more commodious premises in Fletcher Gate. In due course the sons of both brothers joined the family concern, and it was John’s son Samuel Morley who was to become the great figure in the business and one of the most notable of Victorian manufacturer/philanthropists. Samuel became involved with the firm in 1825, and on his father's retirement in 1840 took charge of the London operations of I.& R. Morley.

In Nottingham Richard Morley died in 1855, and his son Arthur followed only five years later at the early age of 48. So it was that Samuel Morley assumed complete control of the business in 1860. The life of this remarkable man makes fascinating reading. He presided over a vigorous expansion of the business, setting up a form of old age pension provision for his work people. He was briefly an M.P. for Nottingham, being unseated because of the illegal conduct of some of his supporters during the election, but later represented Bristol in Parliament for some years. He took a deep interest in education and was responsible for the establishment in Nottingham of the first separate public library in the world for children. He declined a peerage in 1885, the year before his death, and was for years commemorated by a statue in front of the Theatre Royal. This statue was taken down and cleaned preparatory to a move to a more appropriate setting in the Arboretum, but in course of the move it fell off a lorry, sustaining so much damage that it was deemed to be beyond repair. It was replaced by the bronze bust of Morley, executed by Joseph Else, principal of the College of Art, which still graces the Arboretum.

With the move towards a factory-based hosiery industry, Morley's needed further premises in Nottingham, and a search was made for a building which would accommodate a large number of workers under one roof. One such was found not far from the Morleys' old home at Sneinton Manor; this was Cropper's lace factory in Lower Manvers Street, which occupied a triangular plot of land bounded by Newark Street, Lower Eldon Street and Manvers Street. This building was bought in 1866 as part of Samuel Morley's development of the business, and some £27,000 was spent in fitting the factory out for Morley's purposes. The choice of this site was influenced by the fact that hosiery making had long been established in New Sneinton, and there was, in consequence, plenty of skilled labour available on the doorstep of the new factory.

Several hundred people found employment at Morley's newest enterprise, with hundreds more earning a livelihood as out-workers. Many of them lived within yards of the factory, whose five-storey bulk towered over the tightly-packed houses nearby. Within a few years of the opening of the Manvers Street factory I.& R. Morley suffered two outbreaks of fire, one of them regarded as serious. These were, though, nothing compared with what was to come. By 1874, when our story reaches its climax, Morley’s had acquired two sub-tenants who occupied spare accommodation in the factory; these were a hosier named Keywood and a silk, merchant called Sharpe. In late August of that year Mr Sharpe was away on holiday in the Isle of Man. One trusts that his vacation had been an enjoyable one; it was to be interrupted by some very unwelcome news.

So the scene is set. On the evening of Friday, August 21st the workers left the factory at half past five or six, at which time all was well. The night watchman, accompanied by two retriever dogs carried out his routine patrol of the premises. He later told a reporter that about 11 p.m. he had smelt what might have been something burning, but was not alarmed as he had often experienced similar smells before on occasions when nothing was found to be wrong. Friday turned into Saturday, a clear windless night, which, taken with the slightly isolated site of the factory on its triangular 'island', proved to be providential. About 2.30 a.m. the watchman was about to make himself a hot drink when he saw to his dismay smoke, but no flames, pouring out of a room immediately over the cotton cellar. He had, in the course of his patrol, been in the cellar and the room above it, but had found nothing amiss. The horrified watchman opened a factory door and called to P.c. Martin, who was on duty nearby. The constable roused the neighbours, and willing hands set to work with the factory’s hose reel, while others set off to fetch the fire brigade. Such, at any rate, was the watchman's version of events. It is typical of the muddle and confusion attending Nottingham's nineteenth century disasters that no one seemed to know exactly what happened at the crucial time. The Nottingham Guardian related that passers-by alerted the watchman, and that one P.c. Earp was on duty in Manvers Street at about 2.30 in the morning when he saw flames issuing from I.& R. Morley's, and so hurried to the police station to raise the alarm and summon the brigade. Whatever the truth of the matter, what happened next was the ludicrous failure of the fire-fighting provision at the factory. Although a cistern was situated in the factory used in such emergencies, it was found to be almost empty, and buckets of water had to be pressed into service. The watchman, doubtless glad to say anything which might point the finger of blame at someone else, later observed that, had the cistern been full at the outset, the factory hose might have managed to put out the fire. Within fifteen minutes the fire engines arrived, but flames were now belching from various parts of the building, and occupants of houses in the neighbourhood were leaning from their bedroom windows crying 'fire'. These cries, the smell of burning, and the glare in the sky brought out several thousand people into the streets, all anxious to help, many fearful for their threatened livelihood, but few with much idea of how they could assist the fire brigade.

The arrival of the steam fire engine brought no immediate relief. Superintendent Knight ordered the engine to be positioned in Manvers Street and connected to several fire hydrants, including one in Carter Gate said to be 'the best in the town for such occasions'. Disastrously, however, great difficulty was experienced in obtaining an adequate supply of water from the mains and the water works officials had to be contacted before the supply could be improved. By the time that the steam fire engine and its attendant manual engine were connected to hydrants in Fisher Gate which gave a sufficient head of water for them to be able to play their hoses effectively on the flames, a crucial hour had been lost. This delay, said the Guardian, 'was a serious matter, for, undoubtedly, before any quantity of the opposite element was discharged on the flames the fire had got hold of the lower parts of the building, and was devouring everything before it.' The Guardian took a dim view of this incompetence: 'How it is that the police authorities cannot at once procure a good supply of water on such occasions without the necessity of having to call in the aid of the Water Works Company upon an emergency, we do not understand'. After the fire several voices were heard to suggest that water should have been drawn from the nearby arm of the canal to fight the fire, but it was explained that there were practical reasons why this could not have been done.

The outbreak of fire occurred in the main block of the factory fronting Manvers Street and spread quickly, aided so it was said, by the fact of the factory floors being 'literally steeped in oil', which had dripped from the machines. It was suggested that, to have gained such a grip on the building so soon after being detected, the fire must have been smouldering for an hour or two. Not only local people were disturbed by the blaze. The sky all over Nottingham was lit up by the fire, and onlookers were attracted by the glare from as far away as Hyson Green. Thomas Hill, Morley's resident partner in Nottingham, was roused by the police and, as he hurried to the scene from his home in Waverley Street, was able to see the architectural features of Holy Trinity church in Trinity Square, so intense was the light in the sky at 3 am. When he arrived at Manvers Street Mr Hill saw a sight which, related the press, 'grieved the heart'. The Nottingham Daily Express considered the spectacle to be 'One of peculiar grandeur'. The roof 'fell in by instalments, sending the sparks in all directions, and adding to the magnificence of the scene'. Some idea of the scale of devastation may be gained by the fact that the collapse of the roof was heard as far away as Clifton and Ruddington. Later in the night the imposing Manvers Street front of the factory fell in a series of two or three immense crashes. The noise of the collapse was audible at Radford and other surrounding villages, while sparks and embers rained down over Victoria Street and Mansfield Road, and streets in Radford were strewn with ashes. All this, it should be remembered, happened on a calm night, with no wind to waft the debris away. The absence of wind was no doubt responsible for the escape of a wing of the factory behind, and at right angles to, the Manvers Street pile, and local householders felt that even a moderate breeze would have fanned the flames on to their homes. As it was, many houses suffered badly blistered doors and shutters, and parents evacuated their children to a safer distance.

The scene was by now awesome, and the press described it in a purple passage which could hardly have been appreciated by the distraught Mr Hill. 'As one piece of material then another gave way, the 'roarer' went upwards, carrying with it hot embers and rendering a sight awfully grand - awful in its consequences and grand in its appearance to the eye of the cool curiosity seeker.' Despite the best efforts of the firemen, 'the feeble efforts of the water were as the phizzing squib directed at a giant who goes on treating his antagonist with silent contempt.' Iron glazing bars melted and broke, while costly new machinery crashed down through the gutted building. The valuable Paget and Cotton's patent machines were utterly ruined, and even the machinery not destroyed by the fire was severely damaged by water. The fire made 'short work' of the luckless Mr Sharpe’s silk Rooms, but the safe containing I.& R. Morley's books and documents was rescued after a good deal of difficulty.

Astonishingly no one was seriously injured, though one fireman was pinned by wreckage to a wall in Manvers Street opposite the factory as falling bricks rained down about him. The fire brigade tackled the blaze with courage and determination, some firemen stuffing socks from I.& R. Morley's stock into their mouths for use as smoke filters. The Nottingham Guardian praised their endeavours, but concluded that 'Nothing could now stay the progress of the flames, which rose into the sky and illumined the dawning heavens with a ghastly and unnatural glare, upon which the gaze of the spectators dwelt as if under a species of fascination.' The Guardian believed that the firemen laboured under the added handicap of the fire spreading especially quickly as a result of gas explosions in the lower floors of the factory. The paper singled out for mention the bravery of a group of firemen under Superintendent Knight, who climbed into the burning factory through a fifth floor window in Newark Street, and saved a large quantity of valuable silk while the fire was actually bringing the ceiling down upon them.

Morley's factory was a sad spectacle on Saturday morning. One reporter wrote that 'The factory front in Manvers Street is about 200 yards in length, yet there is not a vestige of even the wall, to say nothing of the interior, which can be called worth the carting away.' The ruin reminded the journalist of 'the result of some dreadful battle and bombardment, looking more as though it had been attacked by cannon from without than fire from within.' The fire brigade was still soaking the debris with water, while dense smoke rose over the neighbourhood. Hundreds of shocked employees of I.& R. Morley were discussing the disaster, and rumour spread that Samuel Morley had said, on the occasion of a previous fire, that 'if the factory had been totally destroyed, he would not rebuild it.' The press vividly described the scene of devastation: iron railings in front of the factory bent double or broken, a lamp post in Manvers Street 'snapped in two as though it had been a piece of pasteboard.' From the wreckage of walls and windows hung bundles of half-burnt hose and lengths of cotton material. The factory chimney still rose above the wreck, though the brickwork around its base had been carried away, 'and it would want no great force to bring it down altogether.' Crags of tottering masonry remained, and the police roped off the streets to prevent sightseers and others risking their lives in the ruins. Some of the workpeople seemed to be almost crazed with anxiety over the likely end of their employment: one girl, who had walked from Peas Hill Rise, was extricated by a policeman from a dangerous situation, with parts of the wreck poised to fall upon her. The Daily Guardian was moved to compassion by the plight of the employees, especially the out-workers 'a great number of industrious females whose subsistence depended on the money earned from this source, and who, when deprived of their means of living are necessarily the most helpless class of any in the community.'

On the Sunday the Nottingham architect R.C. Sutton ordered a builder named Middleton to pull down the bits of the factory which were regarded as dangerous. A man climbed up to pass a rope round the walls, and a heave by his workmates was sufficient to topple the ruined masonry. The occupants of nearby houses had to add clouds of choking dust to their trials of the previous two days.

The local papers varied in their estimates of insurance cover on the building, but it was generally reported that Samuel Morley had been insured for £48,000. He was notified of the fire by telegraph, but was away from home at the time, and local people awaited with trepidation his decision about the future of the Manvers Street factory. One paper expressed doubt that Mr Sharpe was insured, but it turned out that he was covered. The Guardian, while expressing regret that this disaster had struck such a well-known business as I.& R. Morley, observed that the fire 'may teach a wholesome lesson to others employed in the same trade, of the almost absolute impossibility of extinguishing a fire in a lace or hosiery factory when once the flames have got anything like a firm grasp of the premises.'

The gloomy rumour that the factory would not be rebuilt was, happily, quickly proved to be false. Despite having been substantially under-insured - the cost of the fire was over £100,000 - Samuel Morley regarded the Manvers Street site as an important part of his expansion scheme. A new factory rose in place of the old, and actually opened in 1875, the year following the blaze. This was larger than its unlucky predecessor, and was described by the firm as being 'of the most up to date character, equipped with the finest machinery available.' The main block consisted of three floors with basement, and the corners of the Manvers Street frontage were embellished by polygonal turrets with pointed roofs. The general effect was undeniably imposing, if a little forbidding, and the building was a dominant accent in the Sneinton townscape.

For many years I.& R. Morley's Manvers Street factory remained an important employer of local labour, until Morley’s vacated the premises at the beginning of the nineteen-thirties.

Something has already been said about Morley’s enlightened attitude towards his workers. One does not wish to paint an over-romantic picture of life at his factories, or to give the impression that his business tolerated slackness: there is on the contrary, evidence enough to show that a high state of discipline was maintained by the firm. Still, though, there comes through a feeling of benevolence, of real caring in the part of the employers, the positive side of the Victorian values so strenuously advocated in some quarters today. One touching reflection of this came to me in a quite accidental discovery in the Nottingham Church Cemetery. Here I found the gravestone of Gervas Matthews, who died in 1896: the inscription tells the story. 'This stone is erected by the workpeople of Messrs. I.& R. Morley's factory, Manvers Street, Sneinton, as a mark of the high esteem and affection in which he was held as a manager, for 26 years'. We may believe that this was a suitable tribute, not just to Mr Matthews, but to the kind of leadership exemplified by Samuel Morley.

THE NEW FACTORY OF 1874; a photograph taken around the turn of the century.

THE NEW FACTORY OF 1874; a photograph taken around the turn of the century.Even though Morley's had departed from Manvers Street, fire had not yet finished its work at the factory. On the night of May 9th 1941 the building, in common with many others in and around Sneinton, suffered in Nottingham's worst air raid of the war. Bombing left the upper part of the structure gutted, with the top floor ruined. The building was eventually reduced in height, and what survives today is the basement and first two floors of the I.& R. Morley factory of 1875. There is little to remind one of the prestige building which looked down so grandly upon Manvers Street, but a tiny bit of the glory remains in Newark Street. Here, giving access nowadays to the premises of Davisella and the Nottingham Snooker Centre, is an ornate doorway through which the great man himself, Samuel Morley, might well have entered this impressive outpost of his industrial empire.

Anyone wishing to know more about Samuel Morley is advised to read the account of him in 'Enlightened entrepreneurs' by Ian C. Bradley. (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987.)

Photographs in this article appear by courtesy of Nottinghamshire County Library, Local Studies Library.

< Previous