< Previous

TALES FROM St STEPHEN'S CHURCHYARD :

Scholars, smiths and others

By Stephen Best

WITHOUT DOUBT the most frequently visited gravestone in Sneinton churchyard is that of George Green, in the north east corner nearest the Fox public house. His story, though, has been told often enough in the pages of Sneinton Magazine and elsewhere, and needs no repeating here. Not far from George Green’s grave is the slate headstone commemorating the first three wives of Christopher Norton Wright, stationer of Nottingham, and an attempt was made in Sneinton Magazine no. 20 to disentangle the bewildering genealogical puzzle posed by this stone. Readers wishing to sort out Mr. Wright’s complicated family history are invited to turn to that issue of the magazine. There are in the churchyard, however, a number of less well known, but equally interesting, gravestones, and it is the intention of this article (and of some future ones) to bring some light to bear upon these.

To the north of the church, just outside the vestry door, is a coped gravestone ’In memory of Thomas Henry, 2nd son of William and Anne Elizabeth Butler, who departed in his 21st year, Sept. 22nd 1858 . . .' The stone tells a sad story, which turns out to have a surprising number of Sneinton connections. The Rev. William Butler, father of Thomas Henry, came to Nottingham in 1833 on being appointed headmaster of the Nottingham Free School in Stoney Street. (This school was to move in 1868 to Arboretum Street, becoming Nottingham High School). For some time prior to Mr Butler’s arrival the Free School had been anything but a happy place, and much of the discontent there had centred upon the usher, or second master, the Rev. Samuel May Lund. Lund had been reproved by the Town Council, who then administered the school, for his harshness, being accused of gaining the attention of his pupils 'by the operation of Fear, rather than Encouragement'. It was also stated that, as a punishment, he had made boys trail out to his home at West Bridgford, taking their books and lessons with them. Lund was also at odds with the school authorities over the amount of time he was spending on his chaplaincies at the Town Gaol and the House of Correction, at the expense of his school duties. Finally, so much bad blood had developed between Lund and his headmaster, Dr. Robert Wood, that these two had refused to communicate with each other over a period of months. An uneasy peace was eventually patched together, but by 1833 the Council decided that it was time for Dr. Wood to be retired. When the troublesome Lund had the nerve to apply for the vacant headmastership, the authorities, anxious to give the new man a clear and troublefree start, resolved to buy Lund off for the sum of £100 and so ensure that he, too, departed the school. Despite posesessing what seem, to say the least, to have been disagreeable qualities, the Rev. Samuel May Lund was a good friend of George Green. In 1827/8 he was one of the fifty-two subscribers who each paid 7/6d for Green's 'An essay on the application of mathematical analysis to the theories of electricity and magnetism', and he was to remain on such close terms with Green that he became one of the mathematician's executors, receiving, like the other two executors, £50 in George Green's will. In 1838 Lund became curate-in-charge at Awsworth, some six miles distant from Nottingham, and in 1843 was appointed perpetual curate of that village. He was, however, allowed by Bishop's licence to reside away from Awsworth until a vicarage house was completed there. By the year 1839 he was living in Sneinton, and as late as the 1850s was still here, in 1853 at Trent Lane and a year after at Notintone Place, where the Green family had a house. Lund still held his gaol chaplaincy in Nottingham, while a curate looked after Awsworth church for him. It has been suggested that Lund's adherence to Sneinton indicated an unusual devotion to George Green and his family, but one suspects that Lund may have found his duties at the gaol too lucrative for him to give up a residence close to Nottingham. Whatever the truth of the matter, it is a pity that his behaviour at the Free School leaves one with such an unpleasant impression of him. Lund was buried at Awsworth, but inasmuch as he was a friend of Sneinton churchyard’s most celebrated occupant, and was at least partly responsible for the state of affairs which brought the Rev. William Butler to Nottingham, he is an essential figure in this narrative.

Now we must take a closer look at the Rev. Dr. Robert Wood, the other principal character on the Free School stage before Mr. Butler’s arrival. When I began work on this story I expected Wood’s part in it to be a minor one, played out remote from Sneinton. The reader may therefore imagine my astonishment when, quite by chance I found, not fifteen feet from George Green's grave, a plain, flat gravestone inscribed as follows. 'John Thomas Wood, the infant son of the Rev. R. Wood D.D. and Ann his wife: Frances Amelia Wood, an infant: Also Theophilus James, eldest son of the above, born Octr. 31st 1815, died May 11th 1831: Also the Revd. Robt. Wood D.D., died 24th Decr. 1839 aged 80: Also Ann the wife of the above Rev. Robert Wood, died Feb. 1st 1845, aged 65 years’. Surely, I thought, this must be the man I had been reading about: so it proved, and the Dr. Wood of our tale turned out to be for me the surprise packet of Sneinton churchyard. He had come to Nottingham from Cambridge in 1793 to be usher at the Free School, and there is evidence that he, too, could be a difficult customer, being inclined to take upon himself more independence of action than his post as usher warranted. After 26 years in this position Wood was appointed master of the school in 1819, but at the time of his feud with Samuel May Lund in 1830 it became clear that he had not been running the school as he should have done. The authorities found, for example, that Dr. Wood had totally ignored instructions to divide the boys into classes and to conduct half-yearly examinations. In addition to his school responsibilities Wood held a number of clerical appointments. He was at various times chaplain to Nottingham Gaol, vicar of Cropwell Bishop, and 'vicar of Sneinton’. This last-mentioned post was, strictly speaking, that of assistant curate. From 1806 until 1817 the perpetual curate of Sneinton, nominally in charge here, was the Rev. Robert Cox, who lived some seventeen miles off, at Kneesall. The Nottingham Journal of November 10th 1811 reported that Dr. Wood conducted Divine Service in the newly-opened (and very shortlived) church which had replaced the much patched medieval church of Sneinton, and would itself be superseded by a new church in 1839. When rebuked in 1830 over his failings at the Free School, Wood frankly told the Council that longer hours at school would tax 'his years and strength'. Three years later, on hearing the news that Dr Wood, now aged 73, had been offered the living of Wysall, the authorities, as related earlier, determined that he should go, settling upon him a pension of £50 a year for life. Dr. Wood had married in 1814 Mrs. Ann Weston, niece of James Green of Lenton Abbey, and he died at Mansfield on, as his gravestone confirms, Christmas Eve 1839.

Following as he did such a Tweedledum and Tweedledee regime at the Free School, the Rev. William Butler clearly had a difficult task before him. He seems to have worked diligently to improve both the academic standards and the morale of the school. Although a firm disciplinarian he appears to have been liked by the boys, but he was never totally satisfied with the quality of his assistant staff. One unenviable duty of the headmaster of that time was recalled, years afterwards, by an old boy of the school: Mr. Butler came into school one morning after witnessing, as chaplain to the gaol, a public execution outside the Shire Hall just around the corner in High Pavement, and was too overcome with emotion to be able to teach that day.

For many years the Butlers lived, as was customary, at the school house next to the school in Stoney Street, but the prolonged illness of his son Thomas prompted Mr. Butler, in May 1858, to ask the trustees of the school if he might let this house, and move into the country for the sake of the young man’s health, This request was granted and the family quitted Stoney Street. What may seem surprising to the reader in 1989 is that the place chosen by the Butlers as their healthy country residence was Sneinton. They took a house in Belvoir Terrace, exactly where the children's playground now lies on the slopes below Green’s Mill. In 1858 Belvoir Terrace was a highly favoured location, It stood in an elevated position facing south, with open country to the east, and, in front, the scattered buildings of Old Sneinton and the Trent water meadows beyond. Little had changed at Belvoir Terrace since 1834, when the Nottingham Journal had commended the houses there to anyone seeking 'a superior country residence'. The newspaper had further considered that, 'In point of situation, for salubrity and magnificence of prospect', Belvoir Terrace was unrivalled, having in addition 'the convenience of a distance of only about ten minutes walk from Nottingham Market Place'.

So Mr Butler brought his ailing son to Sneinton in the hope that country living would restore him to health. The gravestone in St. Stephen's churchyard records the tragic swiftness with which this hope was dashed: only four mouths after his father had asked permission to move out of the school house, Thomas Butler was dead. The Rev. William Butler remained at the Free School for two more years but, no doubt worn down by his family troubles, was glad at the end of 1860 to hand over the running of the school to another headmaster. In December of that year he left Nottingham to become incumbent of Sandal Magna, near Wakefield. He was still only fifty years old, and had thirty more years of a busy life ahead of him. Mr. Butler left behind him in Nottingham plenty of evidence of his good works. In addition to his labours at the Free School he had been a prominent fund-raiser for the building of St. John’s church, Leenside, and active in the setting up of parochial schools in the town. Since George Green has become incidentally involved in this tale, it ought to be pointed out here that the Rev. William Butler must not be confused with the William Butler who was grandfather to the mathematician.

Not many yards from the grave of Thomas Henry Butler lie a couple with a far more direct George Green association. Close to the east wall of the church is a sombre dark grey gravestone in memory of William and Ann Tomlin and one of their daughters. Ann Tomlin was George Green’s sister and, apart from a girl who died in infancy, his only sibling. Some two years younger than her brother, Ann Green married her cousin William Tomlin on September 21st 1816 at St. Mary's church, Nottingham. Tomlin thus became the mathematician's brother-in-law as well as his cousin. The couple lived in High Pavement, close to St. Mary's, and were comfortably off. In the Parliamentary elections of 1820 and 1826 William Tomlin, 'gentleman', of High Pavement, voted Tory, showing that he shared the political persuasions of his brother-in-law. The winter of 1827/8 found Tomlin, like Samuel May Lund, subscribing 7/6d for a copy of Green's 'Essay', and in 1828 he was, as reported in the Nottingham Journal, a member of the committee of the Vagrant Office of St. Mary's parish. The newspaper gives other indications of public activity: William Tomlin acted in 1839 as a municipal auditor and later in that year subscribed £10 to charity.

In George Green's will, all the mathematician's property in Nottingham (but not Sneinton) was left to the mother of his children, Jane Smith, but Green stipulated that on Jane's death this property, in Charles Street, Wheatsheaf Yard, Warser Gate and elsewhere, was to go to 'my sister Anna, the wife of William Tomlin'.

In response to a request from the mathematician’s great supporter Sir Edward Ffrench Bromhead, William Tomlin wrote in 1845 a brief, and not infallibly accurate, memoir of George Green. This short recollection of Green is, for all its faults, the only account we have of him by a member of the family. In forwarding this memoir to Bromhead, Dr. John Calthrop Williams of Nottingham described Tomlin as 'a very respected man living on his Property in this town'. In addition to income from his own property, Tomlin, although possessing no formal qualifications, appears to have made money by acting as a property agent on other people's behalf - he was evidently a man of considerable acumen. We get some indication of William Tomlin's financial status from his description of himself in the 1871 census. By this date the Tomlins were established as Sneinton residents, having moved in the mid-1850s to a substantial house at no. 4 Belvoir Hill. In 1871 William, at the age of 82, gave his occupation as 'Houses, dividends, interest money', while his wife Ann was listed as 'Proprietor's wife'. Four unmarried Tomlin children were living at Belvoir Hill in that year; of these Alfred Tomlin was described as 'Son and landowner'. Even without the Nottingham property due to pass to Ann Tomlin on Jane Smith's death, the Tomlin family can have had few financial worries. An amusing sidelight on the Tomlin children is provided by a writer calling himself 'Chapman'. In a contribution to the Nottingham Weekly Guardian in 1931 he recalled 'the generous Misses Tomlin, with their eccentric brother Alfred, who wore a straw hat in winter, made long daily peregrinations into the country, and as a connoisseur of 'home brewed' was a welcome visitor at the wayside hostelries’. Ann Tomlin did indeed outlive Jane Smith (Jane Green as she is called on her gravestone next to that of George), but not for very long. Jane died in September 1877, to be followed in 1880 by William and Ann Tomlin: William died on July 17th and Ann just over a fortnight later, on August 1st. The Tomlins both enjoyed long lives, Ann reaching her mid-eighties and William ninety-one.

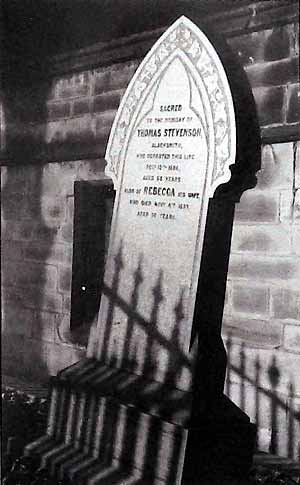

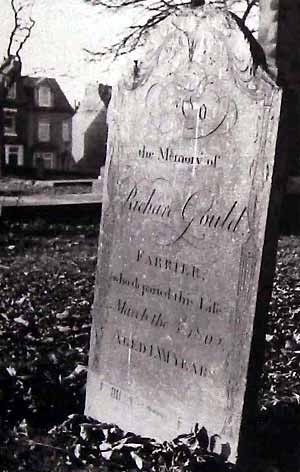

A little while ago it was noticed that Sneinton was, in the 1850s, still thought of as a country place. Few tradesmen exemplified country life more than did the village blacksmith, and Sneinton churchyard contains two headstones proclaiming this occupation. Between the Green and Tomlin graves stands a rather battered slate headstone commemorating 'Richard Gould, farrier, who departed this life March 3d, 1802, aged LXXI years'. A farrier could, in addition to shoeing horses, be expert in curing horse diseases, so Mr. Gould may well have been a very busy man. At the north east angle of the church, adjacent to the vestry, is a stone 'Sacred to the memory of Thomas Stevenson, blacksmith', who died in December 1886, and his wife Rebecca, who lived on until November 1897. A vivid glimpse of the Stevenson family comes in a letter sent to the Nottingham Evening Post in 1947 by the blacksmith's grandson Mr. Edward Stevenson. He related that his grandparents and their sons lived at the forge which stood on the triangular piece of land between Sneinton Dale and Belvoir Terrace, Thomas Stevenson had acted as village constable, as well as assisting the pinder in confining stray animals in the Sneinton pinfold at the end of Sneinton Hermitage. Of the blacksmith’s wife Rebecca Mr. Stevenson had a particular memory. 'My grandmother made some special kind of salve for curing all kinds of wounds, and always kept a jar of leeches under the kitchen sink for curing black eyes, which were very common in those days!'

Black eyes are not unknown in the Sneinton of 1989, but leeches have, I think, disappeared from the local medical scene since the days of Mrs. Stevenson. Though one is sorry that such a colourful character as this is no longer with us, it is hard to lament the passing of her leeches.

Apart from contemporary newspapers, I have found the following publications of great help in the preparation of this article:

H. Gwynedd Green. A biography of George Green, mathematical physicist. 1946.

Nottingham Castle Museum. George Green, miller, Sneinton. 1976.

Adam W. Thomas. A history of Nottingham High School. 1953.

< Previous