< Previous

A CENTURY AGO :

Sneinton through the pages of an old directory

By Stephen Best

THE RURAL FACE OF SNEINTON, seen on a snowy day in the 1890s. On the far left are Green's Mill and the Mill house. Facing the camera are the tall houses in Sneinton Dale, with the Lord Nelson pub to the right of them. The isolated building on the extreme right is St Philip's vicarage, where the Jester now stands.

IF, A CENTURY FROM NOW, people look back and wonder what the Sneinton of 1989 was like, they will regret the absence of a street directory for this year. Historians of the future will be able to refer to maps, electoral registers, and classified directories like the Yellow Pages and Thomson's, and they may also have access to the census returns for 1981 and 1991. Authoritative and reliable though most of these sources are, they lack some of the local colour and what one can only call the 'readability' of the street directory. No such volume covering Nottingham has appeared since 1956, and it is hard to imagine that these rather old-fashioned and quickly out-dated reference books will ever be produced again.

Street directories were not official publications. Put out by commercial publishers, they relied heavily on advertising to help cover their costs, and were aimed mainly at the local business community. They were by no means free from error, mistakes often being passed down from one edition to another without correction. The directories did, however, provide a fascinating glimpse of the places they dealt with, and it is tempting to pick up Wright's Directory of Nottingham for 1889 to see what can be discovered about Sneinton and its inhabitants of just a hundred years ago. Despite the commercial bias of the directories, copies did find their way into the more comfortably-off private households, but with many Sneinton families subsisting on an income of considerably less than a pound a week, it is likely that few local homes could afford the 12/6d (62½p) which was the asking price of the 1889 edition.

At this date Sneinton had for a dozen years been part of the Borough of Nottingham, and it is possible that some of its individuality had disappeared with the passing of its separate status. As will be seen, though, Sneinton retained a character of its own, and was the home of a colourful variety of people. In its introductory pages, the directory drew a thumbnail sketch of the Nottingham of which Sneinton formed a part. The town was described as 'one of the healthiest boroughs in the kingdom', despite an infant mortality rate of over 17%. The textile trades still dominated, there being over 600 businesses engaged in various branches of the lace industry, with a further 150 involved in hosiery manufacture. These trades gave employment to some 15,000 factory hands in the town, though only a handful of substantial lace and hosiery businesses were in Sneinton. Lace manufacturing had for some six years been in the grip of a depression, which had brought great hardship to many workers throughout Nottingham. The directory reported that Sneinton contained 843 acres, and possessed three Church of England places of worship, together with a Congregational chapel and a Wesleyan preaching room. Other amenities included an institute and, in Hermit Street, a free public reading room. The compilers included details of Sneinton Elements, standing 'on rising ground adjoining the Carlton road', and of Sneinton Hermitage, which, even as late as 1889, had 'on the line of its craggy front many grotesque habitations and curious caves.' The directory did not fail to mention the newly-opened Sneinton goods branch of the London & North Western Railway, whose terminus lay at 'the western end of the Hermitage, with a spacious goods station, warehouse and sheds.'

Sneinton in 1889 was thickly built up on the sides adjacent to Nottingham. New Sneinton, the area bounded by Manvers Street, Newark Street, Windmill Lane, Dakeyne Street and Carlton Road, had sprung up in the first half of the nineteenth century, and was very densely populated. To the west of Manvers Street, on the land now largely occupied by the bus garages, was a tract of streets of very poor dwellings, while south of Pennyfoot Street were further houses in what is now a neighbourhood long given over to industrial and commercial premises. Old Sneinton extended from Dale Street down to Sneinton Hermitage: its centre was formed by Sneinton Hollows, Castle Street and Thurgarton Street, which had open fields beyond it. Sneinton Manor, south-east of the church, was in the final few years of its long life, its grounds awaiting the developers who would soon build Manor Street, St Stephen’s Road and Lees Hill Street, On Sneinton Dale, building had extended as far as Victoria Villas, the row of tall houses which ends at what is now 57 Sneinton Dale, but east of here were only a few scattered houses and farms. Colwick Road was a country lane, and there was little development off Meadow Lane. The isolated settlement of Sneinton Elements consisted of a few cramped rows of houses running down the slope between Windmill Lane and Carlton Road, near the northern end of the former. Between the Elements and Dakeyne Street lay open country and the County Pauper Lunatic Asylum in its extensive grounds. In use since 1812, the Asylum had already lost many of its patients to the more recently established Coppice and Mapperley Hospitals, but it would not close until the opening of Saxondale Hospital early in the present century.

HOW THE POOR LIVED IN SNEINTON. Although it was taken in 1914, when the street was on its last legs, this view of Pomfret Street gives a good idea of the conditions endured bv many local people in 1889.

HOW THE POOR LIVED IN SNEINTON. Although it was taken in 1914, when the street was on its last legs, this view of Pomfret Street gives a good idea of the conditions endured bv many local people in 1889.The Nottingham directory for 1889 contained three principal sections. First came an alphabetical list of streets, with the names and addresses of the principal occupants and businesses in each. There followed an alphabetical list of the town’s residents, and a classified directory of trades. Street directories were highly selective in their content, including in the main the gentry, those owning businesses and employing other people, and the selfemployed. The directories therefore tell us hardly anything of the labouring and factory-hand classes of society; my own great-grandfather Robert Hardy, a Sneinton man described as a 'labourer', appears in no directory. Those not in any employment, (apart, of course, from the gentry), were similarly not considered important enough to merit inclusion. Despite these limitations, the directory gives a vivid enough impression of Sneinton as it was in 1889. Even the gaps can be eloquent enough; where a street name is listed without the names of any of its residents, we may assume that its social and economic status was inconsiderable. In this look at the Sneinton of Wright’s Directory, I have fixed arbitrary boundaries to the area under examination. The northern limit has been set along the north side of Southwell Road and Carlton Road as far as Alfred Street South, thereafter following the opposite side of Carlton Road up to Windmill Lane. The eastern and southern bounds are formed by Old Sneinton, Colwick Road, the Hermitage, and Meadow Lane as far as the Nottingham-Lincoln railway line. On the western side all the streets off Manvers Street are included to the line of the now-vanished Water Street and the still extant Plough Lane.

Who, then, were the Sneinton people who found a place in the 1889 directory? Does anything remain today to remind us of them? Taking Old Sneinton as the start of our trip through the book’s pages, we find at 1 Dale Street Mr William Adam Wagstaff, whose initials can still be seen on the terrace of houses in Perlethorpe Avenue, which was built for him in 1902. At 4 Belvoir Hill resided Alfred Tomlin, wealthy eccentric and nephew of George Green; Mr Tomlin figured briefly in 'Tales from St Stephen’s churchyard: 2' in Sneinton Magazine no. 30. Gravestones to members of both the Wagstaff and Tomlin families are to be found in the churchyard. At 1 Belvoir Terrace lived John Webster, churchwarden and retired lace-dresser of Dakeyne Street, who was to be remembered years afterwards as the 'uncrowned king of Sneinton'. A few doors away, at no. 6, was a member of a very famous business family; this was James Liberty, whose relative Arthur established the celebrated Regent Street store. No. 4 Victoria Villas, Sneinton Dale, was the home of William Hugh, headmaster of High Pavement School from 1861 until 1905, under whose headship the school moved in 1895 from High Pavement to Forest Fields. Mr Hugh is not buried in Sneinton churchyard; his grave is in a shady corner of Nottingham General Cemetery. Just across Sneinton Dale, at 1 Victoria Avenue, lived a rising figure in Nottingham's mercantile community. This was Walter Danks, 'Wholesale and retail agricultural and general ironmonger, and iron and steel merchant' of London Road. In a trade publication of the time called 'Nottingham Illustrated', we can see a portrait of Mr Danks, the perfect picture of what W. S. Gilbert would have called 'a pushing young particle.' Mr Danks is quite the dandy, with luxuriant curled moustache, and dark hair parted in the middle. 'Nottingham Illustrated' proclaims that his premises stocked numbers of 'ploughs, hoes, rakes, spades, picks, scythes, turnip and root slicers . . . and all descriptions of tools and ironmongery used by artisans, joiners, builders, etc.' Further down Sneinton Dale, in one of the houses in Irongate Avenue (now Durham Avenue), resided William Henry Selby of Winrow & Son, accordian and concertina makers of Hollow Stone, and Mrs Adelaide Selby. By the wall of Sneinton churchyard, close to the top gate, stands the slate headstone of Mrs Selby and other members of the Winrow and Selby families. Working instruments made or sold by Winrow’s are rarely found, and I am fortunate to possess a Winrow concertina bought for my grandfather about 1884. A few hundred yards beyond Irongate Avenue, in the farmhouse which still stands opposite Highcliffe Road, lived George Allcock, farmer, one of a family well-known in Sneinton to this day. The Allcocks have several stones in Sneinton churchyard, one of them commemorating John Allcock, 'For ten years the respected and munificent church-warden of this Parish . . .'

Some of Sneinton’s grandest houses were in Castle Street, where more of the prominent local businessmen lived. Most notable, perhaps, were Henry Cooper of Sneinton Towers, hosiery manufacturer and partner in the firm of Cooper & Roe, and his next-door neighbour, Frederick Pullman, Mr Pullman was proprietor of the well-remembered drapery store in Sneinton Street, and he left an abiding memorial in the shape of the nearby Pullman Road. His gravestone is in the Church Cemetery, Forest Road, where he lies among many of his business acquaintances.

Colwick Road and Thurgarton Street gave evidence in 1889 of their rural character; their residents included William Shepherd, farmer; Samuel Shepherd, cowkeeper and grazier, and Jabez Crosland, provision merchant and farmer. The Shepherd family has in recent years had its name perpetuated by Shepherd's Farm Cottages in Thurgarton Street. As we have already heard, Sneinton Hermitage was a highly picturesque place. Some houses were built into the sheer face of the sandstone rock, and many had delightful country gardens. One such was no. 45, the home of John Blundell, joiner. Yet another well-known Sneinton family, the Blundells have a gravestone just inside the main gate of the churchyard. Back at the top of the hill, Notintone Place had fewer distinguished residents then than one might have expected. At no. 29 there was, however, the Rev. Frederick Boag, vicar of St Alban’s church, whose neighbour at no. 31 was Caractacus Shilton, The Shiltons were appropriate occupants, since theirs was the family responsible for the building of Notintone Place. Boag and Shilton gravestones may be found in the churchyard, close to the east end of the church.

Elsewhere in the Sneinton of 1889 were other names which may still ring a bell today. At 36 Manvers Stret were the premises of William Henry Trickett, 'machinery broker, waste and marine store dealer'. Long familiar in Sneinton, Trickett’s yard in Trent Lane is now a valued play and recreation area. The name of William Wightman Cooper, surgeon, of 2 Haywood Street, will probably be recognised only by those who have noticed his gravestone near the south east corner of Sneinton church. At 4-6 Sneinton Road was the confectionery business of Francis Claringburn, who sold his wares only a few yards from where, in 1989, a garage still trades as Claringburn & Codd. Although ownership changes, it is pleasant to note a local family name appearing in almost the same spot a hundred years after Wright’s compiled their directory in 1889.

While in Sneinton Road we must pause and salute a trio of sonorously named residents. At no. 70 Mr Theophilus Winterbotham ran his bootmaking shop, while just above, at no, 82, lived the impressive-sounding Abraham Bosomworth Nelson. Over the way at no. 91 was the house of Samuel Brotherhood, whose blind and cornice establishment was down in Pennyfoot Street. Mr Brotherhood was one of only two blind makers in Sneinton, and he leads us into a consideration of the numbers of people following other occupations in the area. At all times we must bear in mind that we shall normally find in the directory only employers and the self-employed.

We do not know how many local people did all their shopping at Sneinton Market, or how many households patronised shops in the town centre and the inner-Nottingham area close to Sneinton. What we can glean from the directory, however, is that while Sneinton was extremely well provided for in the number of shops it possessed, some trades were less in evidence than one would have thought likely. In 1889 the directory listed, for instance, just two Sneinton people who admitted to being pawnbrokers, but it is almost certain that some of the 22 Sneinton clothes dealers and tailors, drapers, and other dealers would have dabbled in the pawnbroking trade. Other local clothing needs were satisfied by the thirty dressmakers and six milliners who were in business here. In these days, when most shoes are sold by a few chain stores, it is interesting to look back on the flourishing footwear trade in Sneinton a hundred years ago; in the crowded streets of this area were no fewer than 33 bootmakers, repairers, and dealers.

Food shops were well to the fore; thirteen bakers (plus one pyclet baker), twenty four butchers and pork butchers, and seventeen greengrocers and fruit dealers supplied the local populace. The directory also shows the presence in Sneinton of 35 provision and spice dealers and grocers, seven confectioners, 19 newsagents and tobacconists, and 17 fishmongers and fish friers. Conditions in 1889 were very different from those of today, under which hygienically processed milk is delivered daily to our doorsteps, and Sneinton a century ago supported twenty milk dealers. One wonders what standard of cleanliness was attained by these dealers, when one reads that milk was stored in butchers' shops, and that as recently as 1906 the authorities were glad to note that cowkeepers in Nottingham were 'beginning to recognise the necessity of frequent washing of milkers’ hands and for the straining and chilling of milk.' A further 46 Sneinton tradespeople gave their occupation simply as 'shopkeeper', and no doubt some of these, too, helped to fill local bellies.

With the universal burning of coal for heating in 1889 (at least, by those who could afford it), it is not surprising that the area gave a living to twenty coal dealers, with a further seven coal merchants at the Great Northern Railway wharf in Sneinton Hermitage, It is, however, odd to find only four chimney sweeps in the directory under Sneinton addresses. Perhaps most householders swept their own chimneys?

The rural aspect of Sneinton was represented by six farmers or cottagers, six cowkeepers and cattle dealers, and several corn merchants and corn and flour carriers. The overwhelming dominance of the horse as motive power was reflected in the presence of two hay and straw dealers, two blacksmiths, and five whip or whipthong makers. It is likely that the two Sneinton men described as 'cab proprietor' were particularly good customers of these tradesmen.

In 1889 most babies were born at home, where, sadly, large numbers of them quickly died. One does not know how many Sneinton families could afford at confinements the services of the six surgeons living in the neighbourhood, but doubtless the three Sneinton midwives of the time were much in demand. With death an ever-present reality for the urban poor, it really is a puzzle that only one Sneinton tradesman in the directory was listed as a 'builder and undertaker'. Probably the dozen or so local joiners and cabinet makers turned their hands to this melancholy but essential trade.

In every directory there appears someone who practised an unlikely occupation, or who managed to carry on two or three oddly assorted trades at the same time. Wright's Directory for 1889 was no exception, and revealed that Sneinton supported a dancing teacher, a felt hat cleaner (Nottingham's one and only), and a man describing himself as a 'lath render'; his job would have been that of splitting wood into laths. Examples of those with fingers in several pies included Thomas Richardson of 4 Pennyfoot Street, who sustained the triple roles of hairdresser, clock repairer, and umbrella mender; and John Charles Nicholson of 81 Newington Street, who enjoyed the varied identities of greengrocer, and paperhanger and whitewasher. Mrs Nicholson traded as a curtain dresser, so 81 Newington Street must have been a lively place; at least the paperhanging and whitewashing would have been done off the premises. We end this short survey of the multi-talented with a nod of admiration in the direction of Samuel Parkin, who at 113 Sneinton Road offered to the locals his services as house painter and bird preserver.

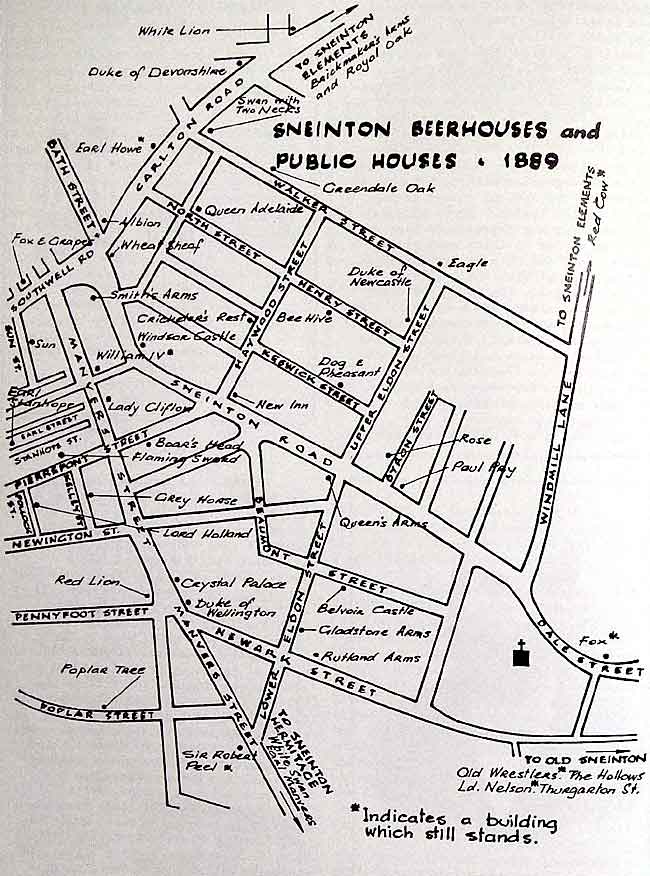

The alert reader will have noticed that this selective and whimsical dip into the Sneinton of 1889 has thus far ignored one essential ingredient of the character of the place. I refer of course to the public house. Whatever anyone else thought of it, Sneinton a century ago cannot have been a place to gladden the heart of the Temperance reformer. The area contained nine beer retailers, and the startling total of forty-four beerhouses or pubs. Beerhouses came about as a result of an act of 1830, designed to discourage the sale of spirits. This allowed a householder to retail beer from his own house on payment of a small fee, with, originally, no need to seek a licence or provide evidence of good character. Within a year a beerhouse existed for every twenty families in England. Of the 44 Sneinton drinking places of 1889, sixteen were classed as beerhouses. It will be noticed that the boundaries drawn for the purposes of this survey exclude some popular local pubs, such as the Sir Robert Clifton in Bath Street and the Stag and Pheasant at the west end of Poplar Street. In reality, therefore, the Sneinton drinker had considerably more than forty four pubs within easy walking distance. The area bounded by Windmill Lane, Dakeyne Street, Carlton Road and Sneinton Road boasted (if that is the right word) 13 public houses, but is should be borne in mind that in 1889 this comparatively small area contained some 900 dwellings. In the streets and courts lying between Sneinton Road and Manvers Street were well over 500 houses, with nearly 600 more between Manvers Street and Water Street. If there were plenty of pubs, there were a great many thirsty people to patronise them.

The range of public house names in Victorian Sneinton provides a welcome contrast to the tasteless and boring trend of today, under which a pub named, say, the Dog and Duck, overnight becomes Winterbottom’s, or something equally silly. Eight of the pub buildings extant in 1889 survive today, though the Old Wrestlers at the corner of Sneinton Hollows and Castle Street has not been a licensed house since the 1950s, and the Fox and Grapes in Southwell Road has for a year or two been masquerading as the Peggers Inn. Two inn signs from 1889, the Wheat Sheaf and the Queen Adelaide, live on in new buildings on different sites from those occupied by their earlier namesakes.

The monarchy was represented in Sneinton by four pubs, the William IV and the Queen Adelaide (a husband and wife team), the Queen's Arms and the Windsor Castle. The aristocracy of the East Midlands was commemorated by the Earl Howe, the Earl Manvers' Arms, the Duke of Devonshire and the Duke of Newcastle; the landlord of the latter bore the inappropriate name of John Wesley. The Dukes of Rutland were well represented a hundred years ago; in addition to the Rutland Arms there was a pub named after the family seat, Belvoir Castle. A further local titled personage giving her name to a beerhouse was Lady Clifton, who had in 1870 opened Wilford toll bridge and Clifton Colliery, works begun by her husband Sir Robert, who died young in 1869. Sir Robert gave his name to the Bath Street pub already mentioned, as befitted such an enthusiastic supporter of the licensed trade as he had been.

National figures of the nineteenth century celebrated in Sneinton pub names included Sir Robert Peel, the Duke of Wellington (whose government had introduced the Beer Act), and W. E. Gladstone, though goodness knows what that sober citizen would have felt about a pub called the Gladstone Arms.

The Earl Stanhope, like the street in which it stood, commemorated a remarkable man who was notorious in his time for sympathising with the aims of the French Revolution, and who invented a printing press, a lens, and calculating machines. Of the national heroes remembered, the Lord Nelson (then standing in open fields) was kept in 1889 by Mrs Emmeline Hornbuckle, of yet another long-established local family possessing gravestones in Sneinton churchyard. One famous Victorian event, the Great Exhibition of 1851, was recalled by the Crystal Palace in Manvers Street.

Two of the old public houses had particularly striking names. In Sneinton Road stood the Paul Pry, which lasted until the 1950s; its landlord a century ago was the exotically-named Edwin Vanini Smith. A Paul Pry was what I suppose later generations would have called a Nosey Parker, 'an idle meddlesome fellow, who has no occupation of his own, and is always interfering with other folks' business.' In 1825 John Poole published a play, 'Paul Pry: a comedy', based on the life of a man named Thomas Hill, but it was never performed in Nottingham, so far as one can tell, and it is doubtful whether any Sneinton resident ever saw it. In Carlton Road, close to Walker Street, stood the Swan With Two Necks. This curious name did not indicate any kind of ornithological mutation, but had its origins in the ancient custom of Swan Upping on the Thames. Since medieval days swans on the Thames have been the property of one of three owners; the monarch, and the City livery companies of Dyers and of Vintners. At Swan Upping each year, the young swans are counted and marked, and have their wings clipped. To denote ownership, the Royal swans remain unmarked, while the beaks of the Dyer’s swans are given one nick, and those of the Vintners two nicks. So what we had in Sneinton was a corruption of 'Swan with two nicks', a bird belonging to the company of winesellers, and a most appropriate name for a pub.

Of the other vanished local pubs, the Brickmakers' Arms at Sneinton Elements reflected the fact that an extensive brickworks stood nearby, in what was then Sneinton Hill, while the Greendale Oak in Walker Street commemorated an ancient Sherwood Forest landmark. The accompanying map will indicate where the Sneinton public houses of 1889 were situated.

A SNEINTON WORTHY OF 1889: William Hugh, headmaster of High Pavement School, who lived in Victoria Villas, Sneinton Dale.

A SNEINTON WORTHY OF 1889: William Hugh, headmaster of High Pavement School, who lived in Victoria Villas, Sneinton Dale.Perhaps those who deplored the evils of excessive drink looked to the schools to inculcate in children the habits of temperance and sobriety. In the Sneinton area covered here were eight educational establishments. Next door to the vicarage in Windmill Lane, in a building which survived until comparatively recent years, was St Stephen’s National School, while Sneinton Church Higher Grade School was close by in Beaumont Street, under the mastership of Charles Frederick Cornish Hole, who lived in Victoria Villas, and was to be remembered in Sneinton as a notable schoolmaster and long-serving organist at St Stephen’s church. In Notintone Street was the Board School, later to be Sneinton Council School and in Pennyfoot Street, by the church, stood St Philip’s Schools; the St Luke's Boys’ School had by 1889 moved to Liverpool Street. There were in addition three private schools; the Albion School in Sneinton Road, Mrs Mary Davis’s day school at 37 Sneinton Hermitage, and Miss Charlotte Sherrington’s school at 26 Notintone Place.

So we could go on: the fascination of a directory is that you can pick one up to check a fact and still be poring over it a couple of hours later, your original query forgotten. Space does not allow us to look closely at Sneinton's only feather dresser, its two herbalists, and its sixteen railway officials: an explanation of the presence in such strength of this latter group would make an article in itself.

My browse through the directory will not have disclosed the whole truth about Sneinton; given the errors to which directories were prone, it may not even have revealed 'nothing but the truth'. For all that, anyone who looks at a Nottingham street directory (especially one published before the Second World War), will find a mine of information on the town and on Sneinton. Scour the attic to see if you can discover an old, forgotten directory, and if you unearth the 1889 edition you can, like me, enjoy a wallow in unashamed centenary nostalgia.

THIS ARTICLE IS ABOUT SNEINTON ONLY, but readers who want to know what the Nottingham of the 1890s was like, and how it came about, will find the following books of great interest:

CHAMBERS, J D. Modern Nottingham in the making. Nottm. Journal Ltd. 1945.

GRAY, Duncan. Nottingham, settlement to city. Nottm. Co-operative Society Nottingham Co-operative Society, 1953.

MELLER, Helen (ed.) Nottingham in the 1880s: a study in social change.

Nottingham university Dept. of Adult Education, 1971.

ILLUSTRATIONS, courtesy of Nottinghamshire County Library, Local Studies.

< Previous