< Previous

A TRAIN OF THOUGHT:

Two memorable outings in Sneinton

By Stephen Best

IT WAS ON A CRISP, sunny Saturday morning in, I suppose, 1949 or 1950 that my father invited me to accompany him on a bus ride. I do not want to give the impression that my childhood was so deprived as to make such an occasion a red-letter day: bus outings were, in fact, regular treats in my youth, but I have especially good reasons for remembering this one. From our house in Forest Fields we walked down to Hyson Green, there to climb aboard a number 44 trolleybus. This invariably indicated a visit to one of our Sneinton relatives; the only puzzle was whether we would be calling in at Manor Street, Lyndhurst Road, or Lichfield Road.

When, forty minutes or so later, our trolleybus slid slowly under the wide railway bridge at Sneinton Hermitage, and accelerated away past Lees Hill Footway, it became evident that Manor Street was not to be our destination on this day. I waited for Dad to get up at Lyndhurst Road or Baden Powell Road, but to my astonishment he remained seated as the bus swished by these stops, to pass beneath the impressively tall brick arch of Colwick Road railway bridge. We were now in unknown territory, and no mistake. From a tract of densely built-up streets we had emerged into what was virtually open countryside, with Colwick Woods looming above us on the left-hand side.

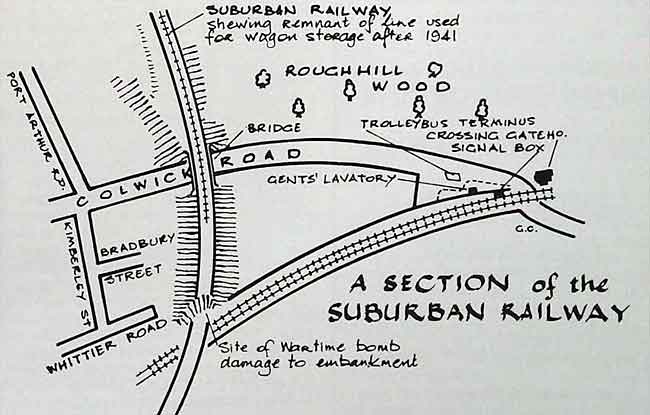

Two or three hundred yards further on, close to the level crossing, was the trolleybus terminus, a spot charged with interest for a ten year-old boy. Here the overhead wires ran round in a wide circle to enable the vehicle to turn, the Bulwell-bound bus beginning its return trip from a sort of bay, separated from the road by an island. I remember seeing here in later years a mobile canteen for bus crews: at first, I think, a smallish van-like conveyance, it was superseded in due time by a converted single-decker bus with a curious hump on its roof. This, I imagine, stored the water needed for the innumerable cups of tea consumed by thirsty drivers and conductors. However, that is by the way, and we must return to the end of the nineteen-forties, and to my first sight of the place. Next to the terminus there stood a public convenience, and as my father led me across the road it might well have occurred to me that this was our immediate objective - it was a parental maxim that anyone who passed a public lavatory without making use of it would rue this omission before very long. To my surprise, however, (this was proving a surprising morning), Dad ignored the loo and opened a gate in the fence separating Colwick Road from the Nottingham-Lincoln railway line. Having closed the gate behind us, he proceeded to climb, with every appearance of aplomb, the wooden stairs of Colwick Crossing signal box. Now my father was a most correct and law-abiding man, and it was unprecedented, in my experience, for him to commit trespass in such a blatant and insouciant fashion. Up we went, though, to find the signal box door open, and all became clear to me. Greeting us was the smiling face of Frank Clarke, relief signalman at the box, and our next-door neighbour. So it was that I entered for the first time (but happily not the last), the tiny, tidy, and highly-ordered world of the railway signalman, so close to the world outside the windows of his box, and yet in a way so remote from it. Everything about the signal box delighted me; the meticulous cleanliness of the instruments, the levers, the floor, the smell, compounded of coal stove, oil and tea; and the ritual of bell codes, controlling the passing of the trains.

I had, ever since I could remember, been intrigued by the ranks of stored and silent wagons on the disused Nottingham Suburban Railway bridges spanning Colwick Road and Sneinton Dale, but the signal box visit was something more personal and more exciting. It was the first of my Sneinton railway adventures. I believe that, before entering his box, I had not the slightest inkling that we had a signalman living next door to us; looking back, this seems in a way to have been the most surprising feature of the whole episode.

Colwick Crossing and its immediate surroundings have seen many changes since that memorable morning. Gone is Colwick Road railway bridge, blown up one Sunday morning in October 1963 with 340 lbs of gelignite. Gone are the trolleybuses and the old level-crossing gates; gone, too, the signal box itself. The multi-storey Colwick Woods Court now towers over an unlikely survivor from forty years ago; against all probability the public convenience remains, though catering nowadays for ’Men’, rather than the 'Gentlemen' it professed to serve then.

My second Sneinton railway thrill must have occurred quite soon after the Colwick crossing outing. Once again I was to feel that I had been admitted to something which, though not actually a secret, was known to only a few people.

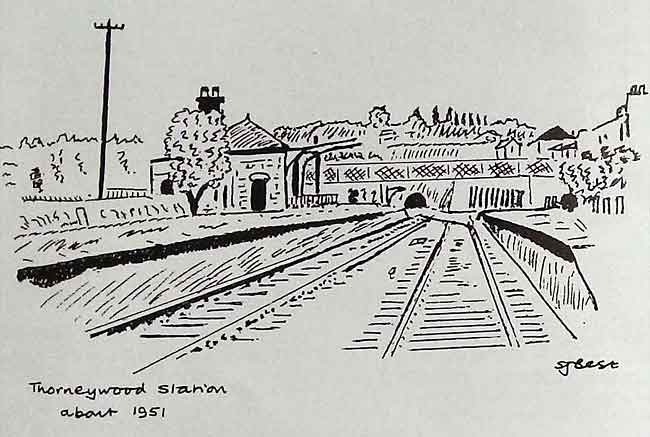

I realise with hindsight that my father was formidably well informed about the Nottingham railway scene, for this was a spectacle very easy to miss. It was nothing less than the arrival of a train in ordinary service at Thorneywood Station. The reader may be surprised to find this claimed as a Sneinton experience, but the station stood within the old Sneinton parish boundaries, near their north-east corner.

Thorneywood Station (originally intended to be named Carlton Road) lay on the Nottingham Suburban Railway, whose Colwick Road bridge has already figured in this narrative. Opened in 1889 with the backing of local businessmen, this steeply graded line diverged at Trent Lane Junction, Sneinton, from the Great Northern line connecting Nottingham with Netherfield, Gedling, Basford, Ilkeston and Derby, rejoining it at Daybrook. Its construction made possible a considerable shortening of the journey to Daybrook and points west, by avoiding the route through Colwick Sidings and Mapperley tunnel; a route often congested with coal trains. The Suburban company also had an eye on the 1930s, but thereafter a sparse goods traffic was the sole source of income. In 1941 a bomb hit the embankment south of Colwick Road, severing the Suburban Railway, and the section of line from Sneinton to Carlton Road was used thereafter for storage of the condemned wagons which, as related earlier, so fascinated me. After the War a goods train sauntered down from Daybrook to Thorneywood perhaps three times a week, and it was one of these infrequent visitors that we were fortunate enough to see.

At this date, Thorneywood was still very much a railway station, although unmistakeably derelict. On one platform was a waiting-room building which still possessed the supports of its vanished platform awning; these stuck out in starkly dramatic fashion, making me wonder whether the station had been an air-raid victim. With benefit of long experience, I now suppose the appearance of Thorneywood Station to have been the result of the curious railway habit of piecemeal demolition, whereby a building is rendered thoroughly unusable, while the maximum possible degree of squalor is achieved. There was, I recall, a nice little goods shed and a surprising number of sidings, while, brooding over the scene from the north end of the station cutting, was the dark mouth of Thorneywood tunnel.

All such details, however, faded into insignificance for me upon the arrival in the station of a small Great Northern saddle tank engine, which proceeded to drop off a few wagons, potter about with a few more, and attach these to its diminutive train. Although the Suburban Line had done considerable business with the brickworks dotted along its route (including the one just across Porchester Road) I think that by this time such trade had ceased, and that the wagons we saw contained only house coal. Dad, I remember, told me how to recognise a former Great Northern engine before it came in sight, by the asthmatic sound of its exhaust, and he greatly impressed me by his easy assumption of what I took to be railwaymen’s jargon. One type of engine he referred to as a 'Jenny Rosspot'; I wonder whether this was a widely used nickname, or one of limited local currency? As already remarked, our sighting of this train at Thorneywood cannot have been long after our signal box jaunt, as all traffic on the truncated stump of the Nottingham Suburban Railway was abandoned in the summer of 1951.

Although the site of the station has long been occupied by a British Telecom depot, there remains ample evidence of its railway past. The long, spidery, lattice footbridge, which used to span the tracks, still links Porchester Road with Marmion Road, and from it the onlooker can admire the splendid arched blue-brick retaining wall of the station cutting. The footbridge was provided by the railway company as compensation for their doing away with the eastern ends of Holly Gardens and Thorneywood Rise. Smothered in foliage below the south wall of the Coopers' Arms pub is the site of the mouth of the tunnel beneath Porchester Road, which led to an incline, up which wagons were hauled to the Nottingham Brick Company’s works. The stationmaster’s house is still in existence: it is the first building on the left at the foot of Porchester Road, and nowadays painted a rather un-railwaylike white. The stationmaster resident at Thorneywood in 1916, presiding over the melancholy progress of the last passenger train to stop here before closure of the station, bore the appropriately haunting name of Luther Faunthorpe.

Although the signal box has disappeared, the GENTS’ LAVATORY still adorns the scene at Colwick Crossing.

Although the signal box has disappeared, the GENTS’ LAVATORY still adorns the scene at Colwick Crossing.Sadly, road improvements (if that is the correct term) have swept away in recent years a picturesque neighbour of Thorneywood Station: one which was almost as stubborn a survivor as the station house. In 1886, a year or two before the opening of the station, there was established, at the corner of Carlton Road and Porchester Road (then named Sneinton Hill and Thorneywood Lane), a small and, it must be confessed, hideous mission church, dedicated to St Clement. An offshoot of St Matthias’ church, it was erected at a cost of £560, with seating for two hundred worshippers. These were expected to come from among the brick-makers and market-gardeners who lived nearby. St Clement’s closed its doors some time around the outbreak of the Great War, but the building lived on for over sixty years in a role not unconnected with its Anglican origins. As E Wragg’s organ building works, it seemed always to exude a faintly ecclesiastical air, with its gimcrack Gothic windows. How such an apparently fragile structure could have borne the weight of a church organ, or how E Wragg and his coadjutors ever got the instruments out through the small doors visible from the road, I never could tell. I dare say that the organs were, in fact, fabricated at Wragg’s and assembled, as it were, on site. (Doubtless some reader will reprove me for my ignorance upon the point). I might add that, many years ago, a friend, on noticing the gradual disappearance of the railway lines from the, by then, totally disused station, suggested whimsically that E Wragg had recycled them into organ components.

Colwick Crossing signal box and Thorneywood Station may be unmourned by most local people, but they retain a place in my affections, at least. And, as a future 'Sneinton Magazine' may show, other railway locations in and around Sneinton still have the power to evoke equally vivid recollections.

< Previous