< Previous

DISCONTINUED LINES:

More memories of Sneinton’s Railways

By Stephen Best

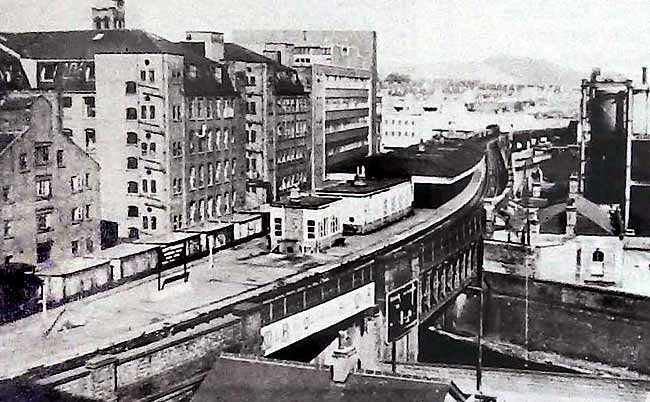

HIGH LEVEL STATION, looking towards Sneinton, March 1965, with an eastbound train of iron ore empties. Picture: courtesy of J F Henton.

In Sneinton Magazine no. 32 I recalled the excitement of childhood visits to Colwick crossing signal box and Thorneywood Station. At least four other railway locations in and near Sneinton have for me similarly vivid memories, and it is a melancholy thought that, as I write, two of these places have changed out of all recognition, while the others face an uncertain future.

No one could ever have claimed that London Road High Level Station was a beautiful spot. Perched on the long viaduct that extended from Weekday Cross to Sneinton Hermitage, it was overlooked on the north side by the sheer, clifflike buildings of Boots Island Street factory. In the shadows below, between the factory and the station, were the far from pellucid waters of the old Poplar Arm of the Nottingham Canal. To the south of the station loomed the uncompromising bulk of the Eastcroft gasholders. It could all have been a model setting for Ewan MacColl's song, 'Dirty Old Town', yet the station held a special magic for me as the first stop on our annual holiday journey to Mablethorpe.

We would board our train of elderly non-corridor carriages at Victoria Station, disturbing innumerable specks of dust as bodies and luggage were set down on the vintage upholstery. I remember the dust sparkling in the shafts of sunlight which penetrated the gloom of the compartment: this was boyhood of course, when it always seemed to be sunny as we went away on holiday.

Hardly had the train got into motion when it had drawn to a atop again, high above London Road, at the unassuming platform of the High Level Station. No matter that we had left Victoria Station only two minutes earlier - we were on our way to Mablethorpe, and London Road was a landmark along the route. Did any holidaymakers clamber on to the train here? I cannot recall, but families living in the Meadows, just beyond Station Street, might well have patronised High Level, rather than hump their cases into town and up to Victoria Station. What I do remember were the large boards, below the station name, announcing that passengers for Nottingham's cricket and football grounds should alight here. The running time from Victoria may have been a mere couple of minutes, but a lot could happen on a railway journey: one year my parents were in brisk dispute at Victoria Station over seats to which another family believed it had prior claim, but by London Road, it seemed, we were all on the best of terms. If, as memory persuades me, sweets were being offered from one side to the other, then there had indeed been a thorough burying of the hatchet. Sweet rationing was still in force, remember, and one did not hand such delicacies round to any but friends. As a postscript to this tale, I should add that our two families were to spend most of the ensuing holiday in each other’s company.

From the train one could see that High Level Station possessed, at platform level, some modestly attractive timber buildings with handsome fretted valances to the long platform awning. Never getting on or off a train here, and experiencing the station only from the viewpoint of the through traveller, I failed to sample the delights of the ground-floor building, which accommodated the booking office. From the vantage point of the viaduct this appeared far from impressive, quite put in the shade by the grand Low Level station (of which more later), and the handsomely chimneyed stationmaster’s house, now gone without trace.

London Road High Level Station had an unspectacular working life of 67 as Victoria Station, it took over from the neighbouring Low Level Station the great majority of passenger services which had previously used that terminus. High Level closed in July 1967, a month or two before Victoria Station saw its last passenger train. After years of commercial occupancy, including a period as an office furnisher's premises, the building at ground level sprang into new life in October 1986 as the 'Grand Central Diner'. An inappropriate name, perhaps, for an old Great Northern station, with an equally inappropriate industrial steam locomotive exhibited outside like a fly in amber, but at least the railway association is perpetuated.

I remarked earlier that High Level Station was a classic example of the landscape of 'Dirty Old Town'; it had all the elements - gasworks, old canal, factory walls. In the years since the closure of the station the gas-holders have been dismantled, and the Poplar Arm of the canal stopped off and filled in. Now the days of the factories are numbered. Boots plan to turn their Island Street site into an international conference centre, sweeping away the old industrial buildings. With this on one side, and a trendy pub on the other, the station’s surroundings will be incomparably smarter than of old. For me, though, the place will never recapture the fascination it exercised as the first stopping-place on the way to the seaside.

If High Level Station was a railway establishment seen only on special occasions, Manvers Street Goods Station was an added spice to our regular weekly or fortnightly visits to my Uncle Jim and Auntie Bella in Manor Street. The nearest trolleybus stop was at the bottom of Lees Hill Footway, close by the cavernous and impressively wide girder bridge which carried the railway lines across Sneinton Hermitage and into the goods station. (If you want to judge just how wide the bridge was, look at the length of the blue-brick abutment, now adorned with murals, that supported the span). Up the Footway we would go, to reach a tall tarred wooden fence at the top of Lees Hill Street, opposite the end of Manor Street. Here was (and, for all I know, still is) a conveniently situated fire hydrant mark: until I was big enough to climb up.

Before me the goods station lay revealed; quite an extensive layout, with a large warehouse at its western end, into which several tracks ran. It was evident that plenty of trade was done here; there were usually dozens of wagons at various stages of loading or unloading, and like all working railway installations of that time, the goods yard looked neat and businesslike, not at all the kind of place that unauthorised persons would stray into, let alone yobbos and vandals. Am I, I wonder, being unduly romantic, investing this scene of thirty-five or forty years ago with a quality it never possessed? I don’t think so, but I am keenly aware of the danger of looking back through the rose-coloured spectacles of the middle-aged. I could, though, never understand why no engine was ever on view in the station - like most lads I thought it a poor railway that did not offer an engine number to be collected. With hindsight I realise that the fact of our usually going to Manor Street on a Sunday morning must have substantially reduced our chances of finding an engine in steam there. I believe, too, that many arrivals and departures at Manvers Street took place during the hours of darkness. One day, however, the long, barren spell came to an end. I had made the journey to Manor Street alone, during school holidays, when a tell-tale cloud of smoke proclaimed that this time my peep over the fence would not be unrewarded. Sure enough, a former Midland Railway tank engine was simmering in the goods yard, and I remember the uncomprehending smiles on the faces of my aunt and uncle as they tried to share my delight. I wish my father had been with me on this happy occasion: I do not know whether he ever broke his duck of locomotives at Manvers Street Station. The everyday scene here was one we all took for granted, yet after the station had been unceremoniously closed in 1966, how I wished that I had appreciated it more, and had made a photographic record of it. The end of the station went unreported in the local press - so many railway closures were on the agenda then that the axeing of a mere goods station like Manvers Street was not considered news-worthy. When the Hermitage bridge was taken down in January 1968, though, the local paper did send a photographer along to record the last of yet another seemingly permanent feature of the townscape - the bridge had in fact stood for a little over eighty years. This busy local railway backwater never saw a passenger train, and operated well away from the public eye. It was, however, an expensive venture, involving some heavy engineering works in its construction. The massive retaining wall remains in Sneinton Hermitage, and over the road from the Sir Robert Peel pub is the dark mouth of the old approach to the goods warehouse. For all these visible reminders, one wonders how many residents of Newark Crescent are unaware that their homes occupy the site of a railway station; a place once contributing to that lost ingredient of the Sneinton night, the sudden rattle and clink, clink, clink of loose-coupled goods wagons being shunted in nearby sidings as we slept, or tried to. Manvers Street Goods Station could not, by its very nature, ever play a part in my experiences as a traveller, but I am glad to be able to say that on one occasion I entered its precincts on business. Sometime in the early 1960s, a resident of Dale Grove, I ventured into the station yard by way of the Newark Street entrance, to visit Bott’s depot, situated just inside the gates. Here, without any inkling of the nostalgia the occasion would one day evoke, I purchased a dustbin.

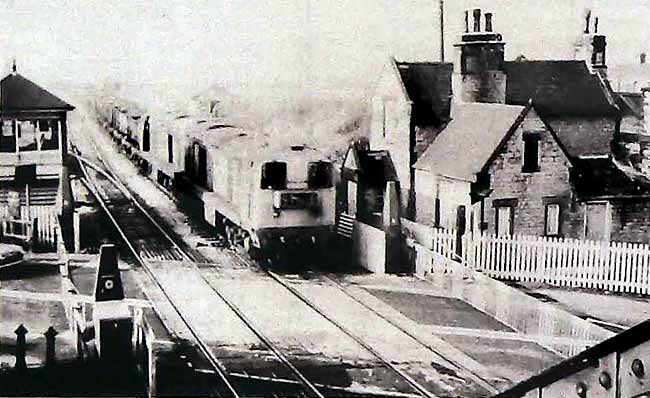

Next to be considered is a spot I did not get to know until I went to live in Dale Grove. Meadow Lane was a natural short cut to the cricket and football grounds, and on walking along it I realised that, at the Sneinton end, it was a thoroughfare dominated by railways as few other streets in Nottingham were. Going from Hermitage Square, one came first to the massive masonry bridge, wide enough for four tracks, which carried the Manvers Street goods branch from Trent Lane Junction: the building of the embankment here in the 1880s had wiped Lund's allotment gardens from the map of Sneinton, The bridge did not long survive the closure of the branch in 1966. A yard or two further down Meadow Lane came the girder bridge taking the line from Netherfield to London Road High Level and Victoria stations. Though it is many years now since the rails were lifted, this bridge remains in situ. A short gap followed before the next bridge, but an eventful gap. On the right was the steep approach road to the railway cattle dock, and on the left a reminder of early days of railways in Sneinton. Fronting on to Meadow Lane, and hemmed in on either side by embankments and bridges, were three little houses, one of them a charming detached villa. Next to this, on the bridge abutment, was a name plate reading 'Ambergate Terrace'. The houses of the terrace (gone before my time) had been squashed together behind the Meadow lane frontage, between the two embankments: the name was a relic of the Ambergate, Nottingham & Boston & Eastern Junction Railway, original owner of the line from Grantham to Nottingham. The site of the houses is now a dismal rubbish dump and graffiti gallery, exemplifying all that is worst in inner-city mess and neglect. Immediately following the houses came the next bridge, the third over Meadow Lane in a distance of well under a hundred yards. As I write, this still carries track, but not for much longer, one supposes. Dating from the 1850s, this was the earliest bridging of Meadow Lane, taking the line from Grantham into London Road Low Level Station and its goods yard. Three railway bridges in a few yards of road would be enough for even the dottiest railway enthusiast, you may well feel, but the attractions of Meadow Lane were by no means finished. A cricket-pitch length beyond the third bridge lay the level-crossing, anathema to the motorist, but delight of the train watcher. Here, as it still stands, was Sneinton Junction signal box, though then it had a real junction to control, and real semaphore signals that you could keep an eye on, and so deduce what the next train movements would be. The crossing gates were then of traditional type, operated by the signalman, who turned a large wheel in his box to open and close them. Across the line from the signal box was an attractive crossing keeper's cottage, as charming in its way as the one which survives at Colwick Crossing. Best of all was the iron footbridge for the use of pedestrians in too much of a hurry to wait for the gates to be re-opened. The footbridge was a great joy to me, not because I was in a hurry - the very opposite was the case. Here one could stand, placidly surveying, as from a grandstand, the passing trains, the signalman at his levers, and the activity in the various sidings close by. From here, too, one could look with something skin to contempt at the impatient motorists fuming at the delay caused by the trains. How I longed to tell them that they would have to wait longer, in traffic jams, if the freight that was travelling by rail was ever, conveyed by road. Now of course it is, and they do.

A COAL TRAIN FOR STAYTHORPE POWER STATION crosses Meadow Lane on February 6th 1970, just a few weeks after the replacement of the old level-crossing gates. In the right-hand corner can be seen part of the footbridge from which the writer watched so many trains.

Perhaps two years ago I decided to take some photographs from the footbridge, as a comparison with those I had taken from this vantage point in the sixties. Never was an enterprise more doomed to failure, for on arrival I found that the bridge had been removed. Now, why, I wonder, was this necessary? Foot passengers now have to wait for the trains to pass - I am not complaining about that; I always did wait. Whatever the reason for the disappearance of the footbridge, we have lost another minor, unsung, but agreeable bit of Sneinton. And one cannot help suspecting that there was a prospective purchaser in the offing, ready to pay a good price for a nice piece of vintage ironwork.

Finally, we come to the major railway monument of the Sneinton neighbourhood. London Road Low Level Station has, over the past few years, become a much discussed building, whose future is a matter of public concern. This is all in happy contrast with earlier decades, during which the station languished in obscurity, deteriorating with every passing month. The current interest shown in the building may well be considered as one of the happiest outcomes of the activities of the Sneinton Environmental Society. A full account of the station’s history appeared in Sneinton Magazine no. 5, and proposals for its future use in Magazine no. 11 and later issues. Suffice it to say here that the station opened in 1857 as the terminus of what was then the Great Northern line from Grantham. At the beginning of 1900 it was served by all Great Northern passenger trains in the Nottingham area, together with trains off the Great Northern and London and North Western Joint Line from Market Harborough and Melton Mowbray. The opening of Victoria Station in May of that year brought about an abrupt decline in the prestige of London Road Station. With the exception of the handful of trains to and from the Joint Line, all passenger services were diverted into Victoria, stopping en route at the new London Road High Level Station. One side of the Low Level Station accommodated the passenger traffic, with the remainder of the premises becoming used for goods and parcels business. In 1944 the surviving passenger services were transferred to Victoria Station, leaving London Road Low Level a humble goods depot.

This was its role when, totally unaware of the station’s chequered history, I first entered it in April 1952, during the Easter holidays. A pal and I, both engine-spotters, had for a day or two been favouring the London Road bridge at the east end of the Midland Station as our observation post. This offered a clear view of trains using the goods avoiding lines south of the Midland Station (invisible from the station platforms themselves), as well as a glimpse of trains passing through High Level Station on its viaduct, a hundred yards or so away. This end of the Midland Station was usually a busy spot; engines were often changed here, and there was usually a pilot engine standing in the bay platform, occasionally attaching a van to a train, or taking one off. An old Midland Railway 4.4.0 passenger engine was a regular on this humdrum duty, and in my mind’s ear I can still hear the clank of the engine’s coupling rods as it pottered about its tasks, so different from the fast passenger work for which it had been designed.

For some reason, (I forget what), we decided on this particular day that the Low Level Station would offer us a better view: perhaps there was an unfamiliar engine in the sidings, perhaps we were just bored. We crossed London Road and, ever law-abiding, asked a uniformed man for permission to go into the station. This was readily given, though it became clear in due course that this gentleman had no business to let us into the Low Level premises, uniform or no uniform. I have wondered since whether he was there only to read the meters. Perched above the buffer stops at the end of the outer platform line, we must have watched the trains for an hour or so, when involved in some daft skylarking, I fell off the buffer stop, landing heavily on the sleepers with my leg broken. After interrogation by a railway policeman, I was carried in state through the echoing trainshed into what must once have been one of the station’s impressive offices, but had by 1952 declined to the status of staff messroom. Someone in authority asked for my name and address, and on hearing the details, asked, ’Not Albert Best's lad?' I was not surprised: wherever I went in Nottingham I seemed to come across people who knew Dad, usually from Dakeyne Street Lad's Club days. One wry consequence of this escapade was the visit to my home (where I lay, leg in plaster) of a senior railway police officer. After enquiring cordially about my health, he told my parents in the pleasantest way that he hoped they were not planning to sue British Railways over my injury - I had, after all, no right to be in Low Level Station in the first place, being, not to put too fine a point upon it, a trespasser on railway property. As I recall, the upshot of this visit was a severe parental telling-off.

My next outing to the Low Level Station occurred perhaps eighteen months after my painful exit from the premises: this was an entirely legitimate affair. My father took me to see the Royal Train exhibition there. This, very excitingly, took the form of a real Royal Train (Queen Victoria's, I think), drawn up at one of the platforms, and headed by a Caledonian Railway express engine of the 1880s, painted a vivid blue, and possessing a single pair of enormous driving wheels. Low Level Station had become totally rehabilitated in my esteem.

Many years passed before I became involved again with the station, in a very different way. With the appearance in 1991 of the first Sneinton Magazine, it occurred to me that the station would make an interesting subject for an article, and I began to look at the building’s place in Nottingham’s architectural and transport history. Here was a major work by T C Hine, one of the town’s finest Victorian architects, with a strong family resemblance to Hine’s huge buildings in the Lace Market. I found it a tantalising thought that T C Hine had been one of the architects who had submitted a design for St Pancras Station, and that his designs had, so far as is known, been lost without trace. Would Hine, I wonder, have reproduced his Nottingham style on a gigantic scale for this great London terminus? After the Sneinton Magazine had taken up the cause of Low Level Station, and had discussed its future, it was heartening to see how quickly interest in the building snowballed. The wide public interest was all to the good, of course, and the refurbishment of the station building and the adjacent Hine warehouse has been greatly to the city’s credit. One only wishes that the trainshed had received equally sympathetic treatment.

I visited the station not long after its abandonment as a parcels depot by British Rail. As with my first visit, thirty seven years before, I had no legal right to be there, but at least I was an innocent interloper, photographing the deserted station for posterity. It was a pity that there had been so many unauthorised visitors, whose only purpose had been mindless vandalism. I found the atmosphere of the station poignant in the extreme. Gone were the trains and the railway workers. Lifting of track in the goods yard had begun, and it was hard not to be affected by a strong feeling of the past. My mind dwelt on the men and women who. had, for a hundred and forty years, worked on the railway in and around Sneinton. Stationmasters, porters, signalmen, shunters, draymen and lorry drivers, refreshment room staff, clerks - all gone, or nearly all. The Sneinton Junction signalman is still at his post in Meadow Lane, but his days are numbered, and another year or two will see the closure of his box. Alone in the gloom of a winter afternoon in Low Level Station, I realised that this was the end of an era in Sneinton.

< Previous