< Previous

A NOVEL VIEW OF SNEINTON:

James Prior's 'Renie'

By Stephen Best

JAMES PRIOR, from a painting by N Denholm Davis.

JAMES PRIOR, from a painting by N Denholm Davis.FEW PEOPLE NOWADAYS, I suspect, read the works of the Nottinghamshire Novelist James Prior. If he is remembered at all, chances are that the book which comes to mind is his minor masterpiece, 'Forest Folk'.

James Prior Kirk (as a nom-de-plume he used his Christian names only) was born in 1851, at Mapperley Road, Nottingham. The son of a straw hat maker, he was intended originally for a legal career, but soon gave up the law as a profession. After similarly unsuccessful forays into teaching, farming, and his father's hat business, Prior eventually settled in Bingham in 1891, remaining there until his death in 1922.

By 1891, James Prior was forty years old, and already the author of several stories and plays, none of which had made much of an impression. He was now, however, to embark on a literary career which saw the publication of six novels at intervals until 1910, establishing for him a fair critical reputation and a wide readership. 'Renie' was the first of these books, followed by 'Ripple and Flood', 'Forest Folk' and 'Hyssop': the last two were 'A Walking Gentleman' and 'Fortuna Chance'. As already mentioned, 'Forest Folk' remains the best known; set in Sherwood Forest at the time of the Napoleonic wars and the Luddite disturbances, it contains fine descriptions of the Nottinghamshire countryside, and displays the writer's keen ear for local dialect. It is not with 'Forest Folk', though, that we are concerned, but with 'Renie', the earliest of Prior's books to meet with any success.

'Renie' is not, I think, a very good book, and it is not suggested here that anyone make the effort of seeking out and reading it. It is, however, of special local interest, in that it contains, among scenes set in various parts of Nottingham, one or two vivid pictures of the Sneinton area as it was just over a century ago. The book's plot may briefly be summarized. The year is 1881, and Irene Boughtflower (the 'Renie' of the title) is living at Bawton in, we assume, Nottinghamshire. The 17-year old Renie learns that she was a 'love-child', and that her elderly mother is, in fact, her foster-mother. Upon the death of this old lady, Renie resolves to come to Nottingham to find a job in the lace trade, and to trace her parents. Arrived in Nottingham, Renie takes lodgings in a house where a friend has a room. A very devout girl, she ventures out on her first Sunday in the town to attend the nearest chapel, and after the service asks the preacher for advice on how she might find her parents. The preacher, the Rev Clarence Millar, suggests that she consult a young lawyer, Frank Jennaway, who is a member of the chapel congregation. The lawyer begins to delve into Renie’s past, armed with a clue: letters bearing the postmark, 'Derby Road, Nottingham', used to arrive at Bawton containing money for Renie's foster-mother. In pursuit of the truth, Jennaway spends hours poring over an old street directory (showing touching faith in the accuracy of these publications). Later detective work involves matching a marked handkerchief with some marked baby clothes. In a not very convincing development, the young lawyer falls in love with Renie. The book's least believable revelation, though, concerns Renie's parentage. It becomes apparent that she is the child of a pre-marital love affair of the Rev. Clarence Millar and his somewhat colourless and downtrodden wife, Nancy; Renie sought his help, remember, on her first weekend in Nottingham. Renie eventually faces Millar with the facts, greatly discomposing him. Mrs Millar is slow in responding to events until, her conscience moved by a brilliant sermon delivered in Mansfield by her husband, she demands to be taken to her daughter. Following a desperate search, they find her at a poor lodging house. It is too late, though - Renie has just died (wasted away, it seems, by hunger and poverty) having, in the best tradition of Victorian melodrama, placed her unpaid rent by her bedside, and - a truly horrible touch - even made her own shroud. Mrs Millar thereupon vanishes from view for ever, while the Rev. Clarence, apparently immune from remorse, departs for the United States. Here he stops abruptly one day while delivering one of his most scintillating sermons, as if transfixed by the sight of something at the foot of the pulpit, something that no one else can see. Millar then tries lecturing and acting, but, his nerve gone, turns to the bottle. After failure in attempts to earn a living as a schoolmaster and newspaper editor, he drifts into the role of company promoter and capitalist. 'Even that', comments the author, 'requires qualities apparently which he did not possess'. Millar is last seen as a billiard-marker in a saloon, afraid to be alone after dark, and consequently never daring to go to bed before dawn.

Throughout the book, the character of Renie never quite convinces, while the dialogue between the middle and upper-class characters fails to sound lifelike. James Prior has a surer touch, though, with his peasants and labourers, and much of their Nottinghamshire speech has life and sparkle about it.

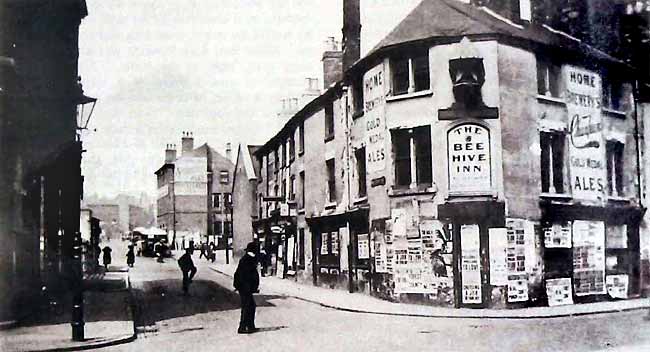

MILLSTONE LANE IN THE 1920s, looking northwest from the corner of Beck Street. The closed Bee Hive Inn is in the foreground, with the Horse & Chaise in the distance.- The pedestrians crossing the street in front of the buses are walking along King Edward Street.

We now come (and about time, you may be thinking) to the descriptions in 'Renie' of places in and around Sneinton. When the heroine first arrives in Nottingham, she is met at the station by her friend, and taken in a cab to their lodgings in Millstone Lane. This street exists today as that part of Huntingdon Street stretching from Beck Street to Howard Street, with the William Booth Memorial Halls towards one end, and the motor parts store on the old bus station site at the other. In its early days Millstone Lane was known as Sandy Lane, and was a stronghold of a lively Irish community. By 1881 it was in a thickly built-up neighbourhood, with, on its east side, crowded yards and courts of poor back-to-back houses. On the west side, looming just round the comer, was the House of Correction. Renie’s reaction to Millstone Lane is of particular interest to me, as, at the time she is supposed to have lived there, my greatgrandfather James Best kept a general provision shop at no. 22, while my great-great-uncle Jack Bell was landlord of the Leg of Mutton pub at no. 44. Renie most emphatically dislikes Millstone Lane. 'Surely this isn't the place?' she asks, complaining of the smell and the dirt. The picture of the street painted by James Prior is certainly not a glamorous one, but it is full of colour and incident, and worth quoting at length.

'Footway and horseway swarmed with children in all degrees of disarray. Every door was open, and every doorstep occupied. There was a woman on one clipping lace, and a couple of neighbours at the same task sat on chairs beside her. There was a woman putting prodigious blue stitches into a man's grey stocking; there was a woman combing the head of a child; there was a man smoking and nursing a fox terrier; there was a group of loud women sitting or standing, with fleshy arms folded over broad breasts, doing nothing but laugh and talk, talk and laugh. A drunken fellow lay where he had fallen. Outside the greengrocer's two men knelt by a box of damaged grapes and sorted them, blowing the sawdust off with a pair of bellows, completely ringed about by interested spectators, men, women and children. Three loafers sat with their backs to the wall, and stretched their feet across the pavement; and so on as far as the eye could see; while children larked in and out like unwashed imps, and fowls picked their filthy food from the gutters, and cats prowled and dogs barked; and there was the squeak of a voice and a harp from the nearest tavern, and the rattle of carts, and the cry of the shrimpseller, and the shrieks and oaths of a man and a woman brawling in a house, and over all a thin strip of pure blue sky.'

This is, I reckon, pretty good stuff, with Prior writing about a place he knew. We are unlikely to find a more vivid description of one of Nottingham's less fashionable quarters in the 1880s. I would like to think that the damaged grapes might have come from my great-grandfather’s shop, but Millstone Lane in the 1880s had several greengrocers, so we cannot be sure. Similarly, it is impossible to identify the tavern; in its short length Millstone Lane boasted not only the Leg of Mutton, but also the Smiths' Arms and the Horse and Chaise, not to mention the Bee Hive on the comer of Beck Street.

Later in the story, Renie goes for a walk with Frank Jennaway. This takes them up Bath Street, towards what is now Victoria Park, but which James Prior calls the Robin Hood Playground. Once again, the author has a keen eye for the local scene.

They had got as far as the Robin Hood Playground. At the first corner there were youths boisterous over the unseasonable game of football . . . Next to them were some girls skipping . . . Then he stopped to look at a group of boys playing at marbles, with the air of a connoisseur . . . But he stayed the longest by some young cricketers. Their bat had been cut out of a bit of paling, probably 'snaked', to use their own delicate term; their wicket was a heap of ragged coats, and their ball was of india rubber . . . In a corner by himself a tiny boy was playing with the dirt, passing it through and through his hands. He had nothing on but tattered knickerbockers and a filthy scrap of shirt. He played and talked to himself and paid no heed to them, nor anybody. Renie bent over him and said; 'Why don't you go home to your mother, little boy? It will soon be dark.' He went on with his play. A small girl who stood by said, 'E ain't got no movver, nor no faver either.' 'And don't want non', he shouted shrilly, and went on playing.'

Renie gives the little lad a penny, and she and Frank cross over Bath Street to Sneinton Market. Here, too, we get the impression that James Prior knew the place well.

The chief of the market was over, the lacesellers were gone, the earthenware-dealers were loading their drays, but Frank looked over the old iron and nondescripts laid out upon the ground, as though he were in quest of something . . . They stood and watched a big, long-haired, uncleanly fellow chopping firewood There were twenty or thirty others looking on, too, as keenly as though they had paid him for the pleasure; and if a wag chaffed him, not too nicely, about the old bed-post he was splitting up, the loud laugh went round. Then they had a good look at a book-stall. Methodist magazines, odd volumes of forgotten novels, dog-eared schoolbooks, a thirty-year-old treatise on the Stamp Duties, ancient ready-reckoners, and the inevitable 'Opere Scelte di Metastasio'; Frank looked through them all, and before he knew why he found himself the purchaser of an oddlooking volume bound in sheep-skin. He rather thought it was a Welsh New Testament, and the stall-keeper 'didn't know but what it was'.'

SNEINTON MARKET IN THE 1890s; a sketch by WILLIAM KIDDIER, from the magazine 'City Sketches'.

SNEINTON MARKET IN THE 1890s; a sketch by WILLIAM KIDDIER, from the magazine 'City Sketches'. We have here, I believe, a glimpse of at least one celebrated Sneinton personality. The long-haired woodchopper described is uncommonly like Tommy Strong, the Sneinton strong man. As related in Sneinton Magazine no. 4, this larger-than-life character was, in his decline, reduced to chopping wood in Sneinton Market, and hawking sticks from a handcart round the nearby streets. The bookstall sounds enticing: I cannot identify its proprietor, but reluctantly feel that the date is too early for him to have been Jimmy Meakin, perhaps the best-known of Sneinton Market's second-hand booksellers, who used to preside over his stall wearing black morning coat, bowler hat, and white cricket shoes.

While in the Market, Renie and Frank encounter the little orphan boy, who has blued his penny on a bag of damaged pears. They then watch a Dutch auction in purses, conducted by 'a swarthy, hooknosed boy, with silver earrings and fantastically bedizened coat'. On their way back along Bath Street, they again pass the playground, where there is further activity to catch their attention.

'It was dusk. Most of the children had gone, but there was a band of whistling, whooping lads playing at stalky, and some devoted cricketers were still pegging blindly away. Their fastest bowler had gone on - your true sportsman never wastes a chance - and wickets and contusions were plentiful. Frank and Renie went round to the quietest corner, up against the cemetery wall.'

Stalky was a Nottinghamshire variant of hide-and-seek, in which the players were divided into two equal groups of hiders and pursuers. It is interesting to note that cricket tactics have changed so little in almost 110 years - fast bowlers still thunder in under darkening skies, to the discomfiture of the batsmen. The cemetery wall survives to this day, separating the park from what is now the Bath Street Rest Garden. In the 1880s the rest garden was the St Mary's Burial Ground, a plot of land given by the Quaker, Samuel Fox, in the 1830s, at the time of a severe outbreak of cholera. In Rente's day it was still open for burials, and had a mortuary chapel in its centre. After the Second World War the memorial stones, with three or four exceptions, were removed and ranged around the boundary walls. One of the memorials left undisturbed was the stone lion commemorating William Thompson - the boxer 'Bendigo' - who had been buried at Bath Street in 1880, just before the events related in 'Renie'.

THE LAMMAS CLOCK on a winter day in 1972, about three years before its demolition.

THE LAMMAS CLOCK on a winter day in 1972, about three years before its demolition.Just off Millstone Lane there used to lie the St Michael's Playground, which provides the final Sneinton (or almost Sneinton) location in the book. Frank Jennaway spends some time here after calling at Renie's Millstone Lane lodgings, only to be told that she has moved away. He is observed in the playground, 'Leaning against a tree by the swings, to all appearance watching a great hulking fellow swinging a dictatorial mite of a child.' Some older readers may remember the playground, but many others will have a clear recollection of its lodge, which served for part of its existence as a police lodge. I used to gaze at this building from the platforms of Huntington Street Bus Station, at the north end of which it then stood, with buses parked in front of it. Its most useful feature gave it the name by which it was always known in my family; the Lammas Clock.

It is possible that, somewhere in Sneinton, a masterpiece is at this moment being written, a novel in which a reader may find, a hundred years from now. scenes evocatively set in the Wholesale Market; outside the Bus Depot, in Victoria Baths Let us hope that such a book is indeed being created. If it should prove no better than 'Renie' it will, I fear, fall short of being a masterpiece. It might, nonetheless, afford someone the fun of unearthing some unexpected bits of local colour, as 'Renie' has done for me.

< Previous