< Previous

EDWARDIAN ENTERPRISE:

A Sneinton Banking Story, with diversions

By Stephen Best

THE NOTTINGHAM & NOTTINGHAMSHIRE BANK, Carlton Road, shortly before its opening; from a photograph in ’The Trader’. On the right is Bennett’s shop at no. 5 Manvers Street.

THE NOTTINGHAM & NOTTINGHAMSHIRE BANK, Carlton Road, shortly before its opening; from a photograph in ’The Trader’. On the right is Bennett’s shop at no. 5 Manvers Street.IN ITS ISSUE OF 28th NOVEMBER, 1908, the Nottingham business periodical 'The Trader' featured an article titled 'The development of Sneinton'. Commenting on current progress on the eastern side of the city, and especially in Sneinton, the article declared this economic activity to be 'a pleasant feature in the life of the municipality'. Much of this development, believed 'The Trader', was attributable to the decision to extend the rails, in addition to providing adequate space for other road traffic. Although he did not say so, the writer of the article may have recognized these Manvers Street demolitions as the first phase of the complete clearance of the densely built-up slum lying between Carter Gate and Manvers Street.

Many houses had been erected in Sneinton while the proposed tramway extension was under discussion: at least 500 of them, according to 'The Trader1, with rents varying from £13 to £24 a year. 'The district known as Sneinton Dale and the 'Hermitage' wears an aspect so altered that it has little resemblance to its appearance less than a decade ago.' Most local residents would have agreed; Sneinton had changed enormously in the course of a very few years. The last of the old properties at the eastern end of Sneinton Hermitage had been cleared away in 1904, the imposing row of new houses backing on to the rock face being occupied by the autumn of 1906. The first few years of the twentieth century had also seen the laying-out of Sneinton Boulevard and residential streets on either side of Sneinton Dale and the Boulevard. Suburban Sneinton was thus expanding in classic fashion, stimulated first by the prospect, secondly by the reality, of a rapid and convenient public transport system. Nor was the building boom finished by 1908. 'The Trader' was able to look forward to further development around the site of the old Lunatic Asylum. This had closed its doors in 1902, upon the transfer of the last of its patients to the new County Mental Hospital at Saxondale. The grounds were subsequently sold, Nottingham Corporation acquiring over nine acres for what was to become King Edward Park: the remnant of the Asylum building which had not been pulled down was taken over by Dakeyne Street Lads' Club, home of what was, at one time, the largest Boys' Brigade Company in England. The rest of the land, including the site of the erstwhile Fever Hospital north of the Asylum, had been sold off for housing. 'The Trader' reckoned that about two hundred houses were to be erected on this land: within a couple of years Spalding Road, St Chad's Road, Denstone Road, St Cuthbert's Road and Worksop Road had been added to the Nottingham street map.

The article went on to acknowledge Sneinton's industrial importance, crediting the neighbourhood with 'extensive lace and hosiery factories in Manvers Street, Liverpool Street, Manchester Street and Roden Street'. Manvers Street indeed had I. & R. Morley's huge hosiery factory, and across the road from this were the plain net lace factories of Charles Hill and Edwin Mellor. As 'The Trader' reported, the area east of Bath Street was in 1908 home to a large number of firms engaged in the textile trades, though perhaps his list of streets was a little off the mark, there being at the time no such businesses with addresses in Liverpool Street or Manchester Street. It would be tedious to list all the Sneinton lace and hosiery firms, and a selection will suffice to show how thoroughly Nottingham's traditional manufacturing industries were represented in this small area of the city. In Handel Street was a further establishment of I. & R. Morley's, while in Aberdeen Street and Longden Street were W. Bancroft & Co., the Nottingham Making-Up Co., and Ashwell, Wells & Knight; respectively frilling, blouse, and hosiery manufacturers. Here too were Maschmeyer & Co's clipping rooms. Bancrofts were later to move the short distance to what had been Windley's factory in Robin Hood Street, the Aberdeen Street building becoming the Salvation Army men's hostel. The site of this one-time hive of industry is now a public car park which, though undoubtedly useful, has robbed this little neighbourhood of its heart. The name of Maschmeyer & Co. serves to remind one of the cosmopolitan nature of the Nottingham lace and hosiery industry of Victorian and Edwardian days. Just around the corner in Roden Street, the Continental flavour was sustained by the presence of Sebastian Albus, hemstitcher, and Adolphe Rosenthal & Co. Ltd., makers-up.

If Manchester Street should sound familiar, yet difficult to place, it might be mentioned that this short street ran from Roden Street to Handel Street. After being declared a clearance area in 1970, as Phase 8 of the St Ann's Well Road Redevelopment Area, it was quickly swept away. Its site is now occupied by Jesse Robinson's premises. Lancashire street names received short shrift in this redevelopment: not only was Manchester Street obliterated, but so also was its near neighbour Salford Street, while Liverpool Street is now barely half as long as it was in 1908.

We now come to the real point of the 'Trader' article on the commercial growth of Sneinton. Its appearance on November 28th, 1908, was no mere accident of time: the following week was to see the opening of a new and important business facility in the district. This was the branch of the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Bank at the corner of Manvers Street and Carlton Road. (In passing, it should be said that the short stretch of road between the bottom of Sneinton Road and Manvers Street is nearly always thought of as Southwell Road, and publications over a period of eighty years have described the bank as being in Southwell Road. Nonetheless Carlton Road begins at the Manvers Street corner, and the bank's correct address is 2 Carlton Road).

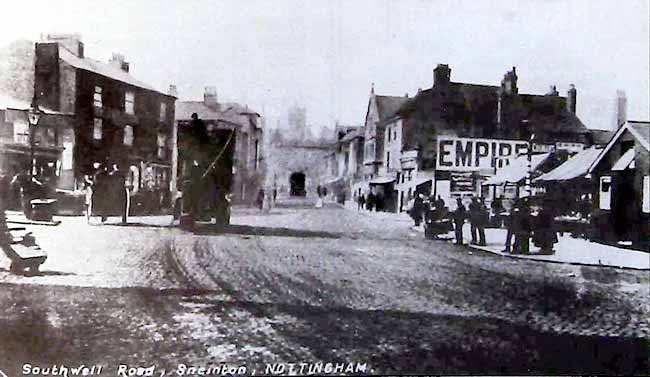

SOUTHWELL ROAD IN ABOUT 1906. The bank was built on the site of Barker's shop, to the left of the bus (one of Nottingham's first, and very unsuccessful). On the right is the wholesale market and, beyond the second shop awning, the Fox and Grapes pub.

SOUTHWELL ROAD IN ABOUT 1906. The bank was built on the site of Barker's shop, to the left of the bus (one of Nottingham's first, and very unsuccessful). On the right is the wholesale market and, beyond the second shop awning, the Fox and Grapes pub.Before the bank was planned, this bit of road was home to Wilcock's, the butchers (a survivor into comparatively recent years), and to the three-storeyed premises of Frank Barker, draper, which occupied what had once been three houses. The new bank building is still in business as a branch of the National Westminster, and I suppose that most of us pass it almost daily without a glance. It comes as something of a surprise, therefore, to read the lengthy and admiring comment lavished upon it in the columns of 'The Trader'. Exterior and interior alike were described in minute detail, and one can imagine prospective customers queueing up on December 1st, opening day, agog to see the splendours of Sneinton's newest commercial building. The reporter thought it a conspicuous and attractive feature on the Southwell Road', and pointed out the advantages of its situation, close to many of Sneinton's businesses and to the market. The Wholesale Market was still a relative newcomer to Sneinton, having moved here in 1900 on being ousted from the Market Place. This move had been bitterly opposed by the wholesale traders, who believed that their livelihood would be imperilled by their being shifted half a mile away from the city centre. Within a short time, complaints had been voiced about the poor facilities provided at the Wholesale Market, but the ramshackle and unhygienic sheds which characterized it were, by 1908, well established at Sneinton, and a bank just across the road was a valuable new amenity. The article felt that the building might be described as 'a development of the English renaissance in style', and pointed out that 'its special architectural features are emphasised by its dissimilarity from any of the surrounding property.' The accompanying photograph certainly bore out this assertion, the bank quite overshadowing the buildings on either side. One of these was James Bennett's newsagent's shop at 5 Manvers Street, displaying prominent advertisements for Lyons' and Stephens' inks, and for the News of the World, which had already been going strong for 65 years. It is a pity that the camera was not a little closer, for this is a rare glimpse of a Sneinton shop before the First World War. The photographer, of course, was indifferent to the attractions of Mr Bennett's premises. He was there to give the bank maximum publicity, and one senses that the article was intended to sing the praises, not only of the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Bank, but also of the various firms engaged in its design and construction. It seems likely that much of the detailed description of the building was a handout from its architects, Swann and Wright, of Brougham Chambers, Wheeler Gate, Nottingham. It is instructive to stand outside the bank today, and to look at it afresh in the light of the assessment made by 'The Trader’. We read that, up to the ground floor windows, the material used is Aberdeen granite; higher up, Sileby red brick with Hollington stone dressings. The corner elevation receives especially detailed analysis: 'A massive-looking doorway with a broken pediment above, supported by two monolithic columns with a coved arch . . . . . . Rising above the keystone of the door is a stone tablet on which is the word 'Bank' [Yes, that does seem reasonable] at the back of which is a semicircular light protected by an ornamental iron grill . . . . . Immediately over the entrance is an oriel bay with a handsomely carved keystone, while over the angle again is a pediment with a chastely carved tympanum.' Nor did the article neglect the bank’s internal features. 'Everything', said the journalist, 'is meant to last.' The reader’s attention was drawn to the quality of the mahogany woodwork and furnishing, and to the splendid ceiling, 'richly ornamented . . . . . divided into four bays with panelled beams. Each bay has an enriched cornice and ceiling ornamented in relief by Jacobean strapwork.' Among other features picked out by the reporter were the open fireplace, the marble mosaic floor paving, and the windows with heraldic shields bearing the city and county arms. The manager's room was separated from the banking hall by a soundproof mahogany partition, surmounted by artistic leaded lights.' The first and second floors were to be let off as offices, three on each floor, with the caretaker's accommodation at the top. As already suggested, 'The Trader' was a source of useful publicity for all who had a part in building the bank. In addition to Swann and Wright, the architects, mention was made of the principal builder, Joseph Shaw of Sherwood Rise, and of Pask and Thorpe, stonemasons, Castle Boulevard, who had done the granite and stone work. The furniture and electrical fittings were supplied by two very well-known Nottingham concerns; Henry Barker Ltd. of Angel Row, and Thomas Danks & Co., Thurland Street.

Today's onlooker will find that the bank still dominates the Manvers Street corner, providing a striking contrast to the mean and meagre buildings attached to it. The bank does, however, look abruptly chopped off at the ends: it really cries out for neighbouring buildings of comparable height. Little has changed since 1908, though it must be said that the present National Westminster Bank signs are far less becoming than the original Nottingham & Nottinghamshire Bank lettering. The casual visitor to the public side of the bank counter can still admire the fine mahogany dado and the sumptuous ceiling: other interior features praised by 'The Trader' may lurk unseen by the general public. Something ought to be said about the bank's changes of ownership. The Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Bank was established in 1834: in 1881 its new headquarters building, designed by Fothergill Watson, was opened in Thurland Street. Eleven years after the inauguration of its Sneinton branch, the Nottingham & Notts, was incorporated into the London County, Westminster and Parr's Bank. This in turn was to become the Westminster Bank and, in 1969, the National Westminster Bank. It is now the only survivor of the five banks which until quite recently ringed Sneinton Market, competing, one assumes, for the accounts of the traders. First of the others to close were the National Provincial at the corner of Bath Street and Handel Street, and Barclay's at the bottom of Hockley. These were followed by the Midland at the junction of Longden Street and Bath Street, and Lloyd's in Southwell Road.

The first manager of the new bank was Mr George Albert Rhodes, who, for the few years he remained at the branch, lived at 9 Castle Street, Sneinton. His brief residence here brought about a small piece of Nottinghamshire sporting history, as on March 24th, 1910, his son Stuart Denzil Rhodes was born at Castle Street. S. D. Rhodes is, as far as I can ascertain, the only Sneinton-bom man ever to play first-class cricket for Nottinghamshire. G. A. Rhodes, his father, himself had a long connection with the game: moving to Mansfield in 1912 as manager of the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Bank there, he remained an enthusiastic club cricketer until in his fifties, and was for a quarter of a century a member of the committee of Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club. Stuart Rhodes first played for Notts in 1930, taking the place of the captain, Arthur Carr, whose wife was ill. He marked this debut with a very good innings of 68 not out. After one further appearance in 1930, and a handful of games in 1931, his county career appeared to be over, but he returned to the side four years later in controversial circumstances. During the summer of 1934, some opponents had strongly objected to the leg-theory bowling tactics used by Nottinghamshire's Larwood and Voce under the captaincy of A. W. Carr: one or two counties went so far as to say they would not play against Nottinghamshire again. The following December saw the Nottinghamshire committee (including, remember, G. A. Rhodes) decide not to re-appoint Carr captain, installing instead joint captains for 1935. These were G. F. H. Heane and S. D. Rhodes, both very inexperienced at this level: Rhodes was 25 and had just seven county matches behind him. He made twelve appearances in 1935, without ever showing his best form, and after August dropped out of county cricket for ever. Despite achieving little with the bat, Stuart Rhodes played a valuable part in Nottinghamshire cricket in 1935: as his obituary notice in Wisden's Cricketers' Almanack for 1990 put it, 'With his enthusiasm he helped heal the county's wounds.' S. D. Rhodes was perhaps better known as a highly successful batsman for Sir Julien Cahn’s XI, the side got up by the Nottingham furnishing magnate and philanthropist. For Cahn's team he scored over 8000 runs, hitting eighteen centuries, and took part in four overseas tours; to the Argentine; to Denmark; to Canada, the United States and Bermuda; and to Ceylon and Malaya. In the words of Wisden again, 'Rhodes's amiable manner fitted smoothly into the style of Sir Julien Cahn’s XI.' As he left Sneinton when a very young child, Stuart Rhodes's memories of his birthplace can have been only of the haziest, if they existed at all. As a native of Sneinton, though, he deserves a place in this brief chronicle. He died in January 1989.

To return to our main theme, the bank has now completed its 82nd year. Whether it achieves its centenary or not will depend on what the planners have in mind for the entire block bounded by Sneinton Road, Eyre Street, Manvers Street and Carlton Road. In addition to the bank, this area contains some of Sneinton's few early nineteenth century buildings, one of them the King William IV pub. It must be hoped that the block will not be sacrificed to the growingly insistent needs of the motor vehicle: it deserves a better fate than to end up as a traffic island.

ALL ILLUSTRATIONS BY COURTESY OF NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY LIBRARY, LOCAL STUDIES LIBRARY.

< Previous