< Previous

PASSENGERS TO SNEINTON:

The early years of Bus and Tram in the neighbourhood

By Stephen Best

THE SNEINTON HORSEBUS at Thurgarton Street in 1901. In the background are the Lord Nelson pub and houses in Lord Nelson Street.

THE SNEINTON HORSEBUS at Thurgarton Street in 1901. In the background are the Lord Nelson pub and houses in Lord Nelson Street.IN 1875, A GROUP OF NOTTINGHAM BUSINESSMEN set up the Nottingham and District Tramway Company Limited, obtaining in 1877 Parliamentary authorization to build and operate tramways, by animal power, in the town and its suburbs. For some twenty years the company ran services of horse buses and trams in Nottingham until, in 1897, Nottingham Corporation purchased it, under powers granted to local authorities by the Tramways Act of 1870.

It was not long before those areas of Nottingham hitherto poorly served by public transport began to ask for better facilities. The eyes of the Corporation's Tramways Committee, however, were fixed on a projected network of electric trams, and several requests for immediate horse bus services were turned down. Sneinton was one district long neglected as far as transport was concerned. Perhaps this was because of its situation, very close to the centre of Nottingham, with many residents easily able to walk the short distance into the Market Place. Whatever the reason, Sneinton was growing impatient, and a formidable body of public opinion was making itself heard. On July 5th, 1898, the Tramways Manager, Alfred Baker, submitted to his committee a report, in response to a memorial from ratepayers and other inhabitants of Sneinton, requesting an omnibus service. Mr Baker considered that, if it were decided to institute a bus service, the best route would be from the corner of Thurland Street and Pelham Street, via Goose Gate, Hockley, Southwell Road and Sneinton Road, to 'a point near Sneinton church'. Two omnibuses and sixteen horses would be needed to operate buses at twenty-minute intervals from 8 am to 10.30 pm, and new stabling would have to be found. A flat fare of one penny would be charged. The manager had calculated what the weekly expenses of such a horse bus service would be. First on his list came the likely wages: three drivers at 24 shillings a week each, 3 conductors at 17/6d, 2 stablemen at 21/-, a nightman at 21/-, and a boy at 15/-, giving a total weekly wage bill of £10.2.6d. On top of this would come the keep of the horses and other expenses; gas, water, bedding, rates and taxes, and depreciation of harness, horses and omnibuses. All this would bring the total weekly outlay on the route to a little over £20. Mr Baker estimated the probable maximum weekly takings as £9.12.0d, a running loss of over £500 a year. His opinion was, that in 18 months or two years, receipts might improve considerably, Although I do not think the service would ever be run at a profit, or even pay expenses.' After discussing the report, the Tramways Committee resolved, in view of the likely losses which would be incurred, and considering 'the transition state of the tramways system', that the matter be postponed for the time being.

A few months later, residents of another part of Sneinton met with a more positive response. A deputation of 'inhabitants of the Carlton Road district' attended the committee meeting on October 4th, asking for an omnibus service to link the city centre and Carlton Road: representatives from the Manvers Ward Liberal Association were also on hand to make a similar application. Once again, a memorial in favour of a service had been signed by a large number of residents of the neighbourhood. The outcome of all this pressure was a decision to establish, for a six months' trial, a horse bus route from the Thurland Street/Pelham Street corner, by way of Hockley, Sneinton Street and Carlton Road, 'as far as the brickyard on the east side of the road.' This was just beyond the Crown Inn (in recent years absurdly renamed Smithy's), the brickyard site now being occupied by Forest Fields College and Manvers Pierrepont School. The terminus lay at what then was the very edge of the built-up area, predominantly open country and allotment gardens stretching away up the hill past the brickworks. The committee resolved that the buses would, to begin with, run every half hour. Stabling for 19 horses was to be hired at Eastcroft, while the Tramways Manager was instructed to buy six buses second-hand from Glasgow, provided that these could be had for no more than £30 apiece.

The committee met again on November 1st, and heard how the Carlton Road service was faring. They were told that, following the setting-up of the Corporation bus service, three private omnibuses had begun to run along this route. The drivers of these 'generally contrived to start a few minutes before the advertised time for the Corporation buses, thus placing the latter buses at a serious disadvantage.' (Those of us who, after bus deregulation in the 1980s, observed rival buses playing Tweedledum and Tweedledee up and down Sneinton Dale and Oakdale Road, may well feel that history was repeating itself). The Tramways Committee decided to draw the attention of the Watch Committee to the antics of the private buses. It was also reported that, on October 20th, 1898, a bus horse had bolted in Carlton Road, injuring two people, and causing damage to a cart and a bicycle. Senior officials and the chairman of the committee were authorized to settle any reasonable claims arising from this mishap.

In its issue of November 1898, the magazine City Sketches praised the Corporation for running a bus service to Sneinton, 'thus supplying a want that has been severely felt for some considerable time.' The magazine went on; Judging by the patronage the service receives, the financial aspect should be very favourable. Possibly the Committee may, in a short time, see their way to connect the increasing suburb beyond Sneinton church.' The following month saw settlement of claims for damage caused by the errant bus horse. These were not inconsiderable: George Hibbert was offered £50 for his injuries, and £43 for his doctor's bills (one infers that 'injuries' included the cost of the cart); Frederick Chamberlain was given £5 for his injuries, and two guineas for doctor's bills, while the third claimant received £12, to make up for damage to his bicycle.

The £30 buses from Glasgow evidently proved not much of a bargain, as in November 1899 it was resolved that new omnibuses at £130 be acquired to replace old ones on the Carlton Road and West Bridgford routes. Peril continued to stalk the passage of the Carlton Road buses, a man named Scarpello damaging his trousers while boarding a vehicle early in 1900. The manager was instructed to negotiate with this aggrieved passenger as to the value of his ruined garments.

All this time, residents of Old Sneinton and the Dale had watched their neighbours in Carlton Road and Sneinton Elements enjoying a regular service, and it was only a matter of time before further agitation was heard for an extension of transport facilities here. On September 11th, 1900, the following item appeared in the Tramways Committee minutes: 'Sneinton suggested bus service: resolved that the consideration of this question should stand over to a future meeting.' Two months later, another deputation of Sneinton residents were at a meeting of the committee, asking that a bus service be established between the city centre and that district.' They were informed that the request would receive 'due consideration'. During November 1900, a pointer to future developments was seen when the committee recommended that powers should be obtained for extending the tramway system from St Ann's Well Road, along Bath Street, to Sneinton. Although it took several years, this recommendation was eventually to bear fruit.

On January 1st, 1901, Nottingham greeted the twentieth century by inaugurating its network of electric trams: perhaps it is not surprising that another long-awaited extension to the public transport system was quite overshadowed by the greater event. A short paragraph in the New Year's Day issue of the Nottingham Daily Express tells the story: 'A new service of buses commences this morning in the city: viz, to Sneinton. The route will be along Parliament Street, Coalpit Lane, Sneinton Street, Sneinton Road, and thence to Sneinton Dale - a district which has greatly developed in the past few years. Two new buses have been provided for the route.' It is ironic that, having minuted in great detail in 1898 the costs and likely route of a service they decided not to run, the committee made no minute of the actual starting of the Sneinton Road route. From photographic evidence, the terminus may be assumed to have been the Thurgarton Street/Trent Road junction. A well-known view, here reproduced, shows the Sneinton horse bus near Thurgarton Street Post Office, with the Lord Nelson in the background. The crew pose in their smart uniforms, while a gentleman in a curly-brimmed bowler hat enjoys his pipe on the upper dock, and a fat man, bearing a striking resemblance to Fred Emney, gazes stolidly at the camera through the bus window. On April 8th the Daily Express commented on the success of the new service: ’The 'bus service to Sneinton, which was inaugurated a short time ago, has, I believe, been much appreciated by the residents in that growing neighbourhood, and it is likely the service will be made more frequent. At present the buses run every half-hour, and the people in the neighbourhood are anxious for a quarter of an hour service.'

We now encounter, for the second time, a strange reticence on the part of the Tramways Committee minutes. Some time before the end of May 1901 the horse buses ceased to ply along Sneinton Road, being re-routed via Manvers Street instead. Unlike Mr Scarpello's trousers, this change was not deemed worthy of inclusion in the minute book. What is recorded there is the reading, on June 4th, of a letter from the Rev. Arthur Murray Dale, vicar of Sneinton, asking that 'the omnibus route to Sneinton Dale' revert to Sneinton Road, rather than continue via Manvers Street. The chairman stated that the Manvers Street route had been tried as an experiment, and had proved much more convenient to the general public, as well as being easier to work. The latter route was, therefore, to be continued. Not only do the Tramways Committee minutes omit any further mention of this route change, but the local papers also seem to have ignored it. At least, if the Nottingham Daily Express made any comment on the matter, it eluded me entirely when I examined its issues for the first half of 1901. One is forced back to Mr Dale's letter, or rather, letters, which survive in Nottinghamshire Archives Office, as part of a file of Tramways Department correspondence.

The Rev. A. M. Dale's name was not unknown to Corporation committees; he had, in September 1899, written to the Works and Ways Committee, complaining 'that streets within the district were not properly watered or cleansed.' It was stated that Sneinton's streets were receiving the same attention as streets elsewhere in the city, and the Town Clerk was told to reply to the vicar in these terms. To go back to 1901, however: Mr Dale wrote, on May 25th, in vigorous vein, 'Will you kindly ask the Tramway Committee to return to the original route for the Sneinton Omnibus? The district served formerly was the more populous, and made considerable use of the conveyance to and from the market.' The vicar added that he would not have written without first consulting local opinion, but seemed uncertain as to whether he was acting as champion of the Sneinton man-in-the-street, or simply indulging in special pleading as a local notable. He continued, 'I think also I have reasonable cause of complaint as on the faith that the omnibus would use this route I subscribed to the clock and in addition to that I am one of the largest ratepayers in the District. It seems rather hard that such a change should be made without first asking our opinion on the subject . . Quite where the clock in question was, I do not know, and it is also a pity that the correspondence files preserve only letters received by the Tramways Department, but not letters sent out. The reply of John Aldworth, who had succeeded Alfred Baker as manager, can only be guessed at, but it clearly failed to calm the ruffled Mr Dale, who returned to the fray in a letter dated July 20th, 1901. Stating that his first letter had been 'an expostulation on the part of one of the largest ratepayers in the district', he complained, 'I do not in the least consider Mr Aldworth's letter conclusive. In the first place he virtually tells me that the road is absolutely useless for the purpose it is intended. For if it is unsuitable for busses it is equally unsuitable for all heavy traffic, and should be at once altered in such a manner as is necessary. I am quite certain that it must be the badness of the road and not the steepness of the hill that prevents the working of the vehicles up Sneinton Hill, for I notice and have noticed that for many years until quite lately heavier vehicles have been worked up the far steeper hills in the Mansfield and Derby Roads. I may be wrong, but it seems to me that sufficient consideration is not paid to large ratepayers who have the misfortune to live in this district. With regard to many modern conveniences we are worse off than some of the outlying villages ... It sounds very much as if Aldworth had cited the steepness of Sneinton Road as the reason for the change to the Manvers Street route, and indeed the advantages of this level route were to be repeatedly emphasized over the next few years, while planning for the Sneinton trams was progressing.

Nobody at the Tramways Department, one feels, could have been left in any doubt that the vicar considered himself a leading ratepayer, but one wonders what his parishioners would have made of his contention that it was his 'misfortune' to live in Sneinton. Mr Dale was not, however, to bear this burden for much longer, leaving in 1902 to be rector of Tingrith, Bedfordshire. He died in 1927, having become a Roman Catholic. If the vicar took after his father, he would have been able to take controversy and conflict in his stride, for the Rev. Thomas Pelham Dale had been in trouble when, as rector of St Vedast, Foster Lane, in the City of London, he 'instituted ritualistic practices'. After what were described as 'protracted legal proceedings', he was sent in 1880 to Holloway Prison. It was suggested in some quarters that the real reason behind his persecution was that he had reformed a church endowment which had provided his churchwardens with undue perquisites. Compared with all this, his son's disputes with the Corporation must have seemed very small beer.

From these clerical diversions, it is necessary to return to the Sneinton horse bus. A study of the available evidence, and of the street map of the day, suggests that its likely original route was from the Market Place, by way of Parliament Street, St John's Street, Coalpit Lane, Hockley, Sneinton Street, Southwell Road, Sneinton Road and Sneinton Dale. It seems reasonable to suggest that the revised route ran from Southwell Road, along Manvers Street, Sneinton Hermitage and Thurgarton Street. Although 1901 saw the beginning of this horse bus service, it witnessed the end of another. In October it was decided to abandon the Sherwood Rise bus route, the redundant horse cars being transferred, as needed, to the Carlton Road and Sneinton services. The Sneinton buses were running every 20 minutes from 7.50 a.m. until 10.50 p.m., but in December were cut back to a half hourly service. Some much more startling news about horse bus services followed in March 1902, when it was announced that they were operating at such a loss that they should be discontinued, with arrangements being made for private bus owners to work them in place of, and on behalf of, the Corporation. Mr Walters Bamford, whose horse bus service along St Ann's Well Road had been killed off by the electric trams which had begun operation there the previous month, informed the Tramways Committee that he would be willing to run two buses each on the Carlton Road and Sneinton routes, with the same fares and timetables as those currently in force. Bamford's conditions were that the Corporation should sell him four buses and twelve horses for £300. The Tramways Manager, however, failed to agree with him over the selection of suitable horses, so this deal fell through for the time being.

April brought a fresh agreement: two buses on the Carlton Road route, together with six horses, were to be sold to Bamford for £200, leaving the Sneinton service to be operated by John Commons. The latter was foreman at Muskham Street tram stables, and. in a sort of early management buy-out, took over the running of the Sneinton, Old Lenton and Radford horse buses. He was to employ those men, now engaged in connection with the omnibus services, as Mr Aldworth may not desire to retain in the service of the Corporation'. Should Commons discontinue running his horse buses before the introduction of Corporation electric trams to the areas concerned, the Tramways Committee reserved the right of ending his tenancy of the Muskham Street stables at short notice. So, for the remainder of its existence, the Sneinton horse bus service was worked by Mr Commons. As we shall see, the Carlton Road route was to enjoy (if that is the right word) an altogether more chequered life.

Discussion of the projected Sneinton tramways took on more detailed form. In September 1902 it was suggested, at a City Council meeting, that the network should include a line along Sneinton Boulevard. In the end, although Manvers Street and Colwick Road became tram routes, the Boulevard did not, and it has, up to the present time, played only a very minor role in Nottingham's public transport system. In January 1904, the City Engineer proposed a tramway along Bath Street, Sneinton Road, Sneinton Hollows and Colwick Road. The Tramways Committee quickly responded by objecting to the Sneinton Road-Sneinton Hollows section. It is puzzling that the City Engineer suggested Sneinton Road, since the Tramways Committee had, as early as September 1901, resolved to omit that thoroughfare from any of its Parliamentary plans for tramway systems. The committee repeated that the flat Manvers Street and Colwick Road route was their preferred one, recommending that this was the route along which future planning should be directed. This decision was to result in the demolition of some sixty old houses in Manvers Street, to make the roadway wide enough for a double line of rails: the manager, John Aldworth, had a strong aversion to single line tramways with passing loops. Road widening was also to be necessary in Bath Street, involving taking back the boundary wall of the St Mary's Burial Ground, and the removal and reburial of a number of bodies elsewhere in the cemetery. The arguments in favour of a tramway extension to Sneinton were kept constantly before the City Council and the public by the vigorous and sustained campaigning of Councillor John Henry Gregg, one of the Trent Ward representatives. A retired builder, of 32 Lees Hill Street (to which he gave the modest name 'Manor House'), Gregg's tireless efforts were to cam him the status of local hero when the trams eventually arrived. Of this, more will be said later.

July 1905 saw the committee consider a letter from the Trent Ward Liberal Party, protesting against the establishment of any motor bus service in Sneinton. Looking back on what happened shortly afterwards, we may wonder whether second sight may have played a part in this communication. Despite these declared objections, Corporation officials, early in 1906, looked into the possibility of running motor buses on the Carlton Road service. Mr Bamford had stated his intention of continuing with his horse buses on this route, though no longer under any obligation to do so, and the committee decided he should give a month's notice when intending to cease operating his service. At the same meeting, they instructed their manager to obtain particulars of buses, suitable for operation to Carlton Road. Presumably, other municipal authorities had given sufficiently encouraging reports of their experience of motor buses to persuade the Tramways Committee that they were a desirable innovation. It was stipulated that the vehicles should be British-made, and, following reports that acceptable buses were available from Thornycrofts of London, three of these were bought immediately. The motor bus service, replacing Bamford's horse buses, began on March 26th, 1906, running from the Exchange, via Poultry, Victoria Street, Carlton Street, Hockley, Sneinton Street and Carlton Road. Bamford seems, at this remove in time, to have been treated in cavalier fashion, but he doubtless knew what he was letting himself in for when he agreed, in 1901, to work the Carlton Road service. He had in that year written to the Corporation, asking for compensation after the electric trams on the St Ann's Well Road route had brought about the eclipse of his horse buses on that service. His plea on that occasion met with a flat refusal, and he was to be involved in a similar disagreement within a few years. Mr Bamford was, in March 1906, involved in other negotiations with the Tramways Committee. He had agreed to take over the tenancy of the Muskham Street stables from John Commons, operator of the Sneinton horse buses since 1902: Commons's Nottingham Carriage Company had recently gone into liquidation. Walters Bamford was, however, unable to get West Bridgford Urban District Council to give him a licence to operate south of the river, so the Muskham Street deal did not come off.

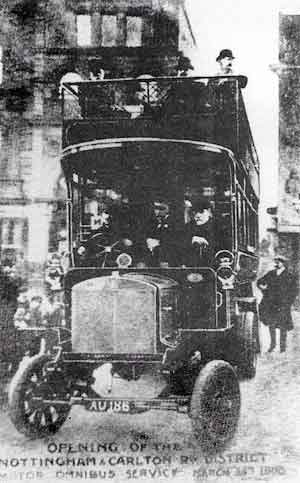

THE CIVIC PARTY aboard a motor bus on the first day of the Carlton Road service, 1906. The building behind the vehicle is Lipton’s grocery shop, which stood at the Beastmarket Hill / St James Street corner.

THE CIVIC PARTY aboard a motor bus on the first day of the Carlton Road service, 1906. The building behind the vehicle is Lipton’s grocery shop, which stood at the Beastmarket Hill / St James Street corner.According to the Nottingham Daily Express of March 27th, the new motor buses were quite an attraction. The paper suggested that Carlton Road was likely to be visited by many who had never before ventured into the neighbourhood, but were agog to sample the delights of the motor bus. The new double-deck vehicles took between ten and twelve minutes to accomplish the journey; they were 'not exactly flyers', commented the Daily Express. The smart appearance of the buses was commended, and it was pointed out that, although upstairs passengers experienced some vibration, the upholstered seats removed 'all discomfort from this source'. The newspaper report ended with the confident assurance that, 'The motor buses arc of course a vast improvement in every respect on the old horse buses', a judgement soon to be proved wildly over-optimistic. Very early in their service, trouble was experienced with the steering gear and fuel supply, the standby bus frequently having to be brought out on to the road to keep the route going. Despite these difficulties, it was decided in April to introduce a Sunday timetable on the Carlton Road service.

After only a couple of months, one of the new motor buses made a tragic mark in local history when, on May 18th, it caused the death of a pedestrian; this was Nottingham's first motor bus fatality. A bricklayer's labourer named William Herbson was knocked down and killed in Southwell Road. Mr Herbson, who lived in Barrows Yard, Windmill Lane, had apparently stepped into the gutter near the Fox and Grapes pub, where he was struck by a bus bound for Carlton Road, and run over by its rear wheel. The driver suggested that Herbson had been struck by the guard of the back wheel, which caught him and pulled him under. The Coroner agreed that this was a feasible explanation, and the jury returned a verdict of accidental death, adding that the driver was quite free from blame. By a strange coincidence, the hapless bus driver bore the name of one of Sneinton's two greatest men; he was called George Green.

In August, work began on track laying for the new electric tram routes; to Colwick Road, and to Trent Bridge via Pennyfoot Street and London Road. During the following months the Tramways Committee was busy finalizing details and reviewing the progress of the works. As mentioned in 'Edwardian enterprise' (Sneinton Magazine no. 37), the knowledge that Sneinton was to be connected to a modern passenger tramway had, over a period of several years, greatly stimulated residential development in the Sneinton Dale and Boulevard areas. It is possible that this development might have taken place a decade or so earlier, had the projected Sneinton station on the Nottingham Suburban Railway ever been built. The Carlton Road buses were constantly on the minds of the committee: it was stated in November 1906 that they had, in their first six months in traffic, made a profit of just £107, and members decided to review the use of motor buses after the introduction of trams in that area of the city. The buses experienced a difficult winter, in March 1907 being re-routed along Parliament Street and Bath Street, because of problems on the Goose Gate and Hockley section of the route. At the same time the outer terminus was moved, the buses struggling up Carlton Road as far as Thorneywood Lane (now Porchester Road). This pushed the route out into a very thinly populated district, but perhaps the intention was to attract traffic from Thorneywood Station, which was adjacent to the new bus terminus. The 1906-7 annual report of the Tramways Committee confirmed that all was not well on the Carlton Road route; the modest profit of the first six months had, by the end of a year of motor bus operation, vanished into a loss of £260.

March 1907 also saw the eagerly awaited inauguration of the Sneinton tramways A trial car was run on March 6th, followed a week later by the Board of Trade inspection. On March 14th, the Market Place - Colwick Road services began, running over new track in Bath Street, Manvers Street, Sneinton Hermitage and Colwick Road. March 15th was the day on which services began along Pennyfoot Street, Fisher Gate and London Road. The opening of the Sneinton route was accorded lavish coverage by the press. The Nottingham Daily Express of March 15th had a rousing welcome for the trams. 'After years of patient waiting Sneinton has at last got its desire, the privilege long enjoyed by every other part of the city, of making the journey between their suburb and the central portions of Nottingham in a comfortable electric car.' Proceedings began with a luncheon at the Exchange, attended by the Mayor and Corporation, and senior officials. Proposing 'Success to the Tramway Undertaking', the Mayor, Alderman J. A. H. Green (not to be confused with Sneinton's celebrated Billy Green) made the first of the day's references-to Councillor Gregg, that sedulous advocate of trams for Sneinton. Reporting his speech, the Daily Express paraphrased as follows: 'So far as they were concerned in the work of that day, they knew their friend Mr Gregg was made happy . . . and those present might possibly say the day had come when Sneinton ceased from troubling and the Council was at rest.' The committee chairman, Alderman Anderson Brownsword, agreed: 'A good deal was owing to Mr Gregg's persistent endeavours and the support he had received from other members for that district.' He considered the Sneinton tramway the finest in the city, embodying as it did the latest advances in equipment. 'All that remained now was for Sneinton people to show their appreciation of all that had been done for them ... by patronising the trams sufficiently to help make a good return.' Mr Brownsword added that the cost of the extension had been £110,000: original estimates had been £57,000 for the tramways, and £38,700 for the widening of Manvers Street and Bath Street. Following him, Sir John McCraith, vice-chairman of the Tramways Committee, tried, not entirely convincingly, to assert that his committee were men capable of withstanding pressure groups. 'He would not like it to go forth that the present extension was entirely due to the constant demand they had had from Mr Gregg and his Sneinton friends. The committee had sympathetically considered the extension, but they were not prepared to proceed with it before the time arrived when they could see their way to its being a success. They congratulated Mr Gregg and the inhabitants upon the accomplishment of the undertaking, and they believed it would be a remunerative branch of the service.'

Replete with their civic luncheon, a large number of municipal worthies then boarded 'two gaily-decorated cars, covered with flags, bunting, and varicoloured lamps': Alderman Brownsword drove the first of these (under qualified supervision), and Alderman McCraith the second. The Daily Express reporter made the most of the incidents of the journey: Ald. Brownsword's tram blew a fuse in Queen Street, and a projecting lamp standard in Parliament Street broke some of the coloured light bulbs, which went off with a loud report. He saved his most purple passage for the journey of the official trams through Sneinton. 'In Sneinton itself, all was excitement. The Market Place and Manvers Street were lined with inhabitants. We gazed down on rows of up-turned laughing faces; fluttered handkerchiefs were the welcome of the women, and hundreds of children cheered and raced the cars. A triumphal entry into Sneinton - and the smile of content on the face of Councillor Gregg never once relaxed.' At the Colwick Road terminus there was a moment of panic when a horse, disturbed by one of the trams, knocked over a perambulator, and a boy was nearly stamped on: 'Happily no one was hurt, the horses became reconciled, and we drank (in tea) to our safety and the success of the Sneinton trams as the guests of Councillor Gregg.'

THE CROWD ASSEMBLED AT COLWICK ROAD RECREATION GROUND listen to speeches marking the opening of the Sneinton tramway, March 1907. In the background one of the decorated floats may dimly be seen.

THE CROWD ASSEMBLED AT COLWICK ROAD RECREATION GROUND listen to speeches marking the opening of the Sneinton tramway, March 1907. In the background one of the decorated floats may dimly be seen.Many local people had indeed assembled in the playing field at Colwick Crossing, invited by the councillor. Alderman Green, the Mayor, paid further tribute to Mr Gregg, and to Sneinton. 'One of the best, if not the best, of the suburbs of Nottingham.' Mr Gregg thanked the Major for 'coming down to poor old Sneinton'. Thanks to the trams, he said, they were no longer a 'poor, isolated hamlet'. A vote of thanks to Councillor Gregg was proposed, Aid. Green describing him as the best friend Sneinton had had for many years. The Mayor added that Nottingham was called the Queen of the Midlands, and that Sneinton was one of the best gems in its crown. The crowd sang 'For he's a jolly good fellow', and tea was served, amid an atmosphere of mutual admiration, in a large marquee. The official party then drove back in the decorated trams, by way of the other new lines, to the Market Place.

Following this outburst of jollification, the Sneinton trams settled down to routine operation. 'Settled' may not be the best word to describe the first few years, since they saw a bewildering number of route alterations. We can see that the current fashion for frequent service revisions is no new phenomenon, and that the Tramways Committee of 1907 were constantly studying passenger traffic flow, and seeking to link the city's residential and commercial centres as effectively as possible. At the outset the Market Place - Pennyfoot Street - London Road trams ran through from the Wilford Road route, and, for a short while, the Sherwood - Station Street service was extended to Colwick Road, via London Road and Pennyfoot Street. This arrangement was to last barely a month. On March 23rd the Basford and Colwick Road services were joined, to form a single long route. Objections to the loss of the Station Street service led, in May 1907, to a Colwick Road circular route being introduced, serving the Midland Station and city centre. Following a three month trial, poor receipts led to the withdrawal of this service in September. It was, however, restored in February 1908, through the pertinacity of, inevitably, Councillor John Henry Gregg.

Despite the significant service developments of 1907, the 1907-08 annual report made gloomy reading, so far as Sneinton was concerned. It was revealed that the result of a full year's working of trams through Sneinton could not be considered satisfactory, receipts averaging less than eightpence a mile. The Carlton Road motor buses were running 'at a considerable loss', proving 'very expensive to maintain, and unreliable in service'. With split pins from their steering gear littering the streets through which they ran, it is hardly surprising that reliability left much to be desired. Even worse, however, was to come, and the committee minutes for May 8th, 1908, had to record a major humiliation: a temporary service of horse buses was proposed instead of the motor vehicles, because 'the present motor busses cannot be maintained in satisfactory condition.' A photograph of one of these unfortunate vehicles, on service in Southwell Road, appeared in Sneinton Magazine no. 37. The Corporation experienced great difficulty in finding someone willing to run this horse bus service for them, and one reads that 'Seldon Brothers and Wentworths had declined to entertain the matter.' Seldons were cab and brake proprietors in Mansfield Road, while Wentworths had a similar business at Derby Road, Wollaton Street and Raleigh Street. Walters Bamford, however, offered to provide two buses, with horses and drivers, to run from the Crown Inn to the top of King Street, via Coalpit Lane, (renamed Cranbrook Street between the wars), at a charge to the Corporation of ninepence per mile run. The horse buses were not going to tackle the hill up to Thorneywood Lane, but would use their old terminus.

It was estimated that a 20 minute service would result in a £300 a year loss to the Corporation, with a half-hourly one likely to incur an annual shortfall of £325. The committee decided in June that Bamford should run his horse buses every 20 minutes; the Corporation was to provide conductors and take all the receipts, paying Bamford his fixed mileage fee. This arrangement was for two years, starting on June 16th, the day after the withdrawal of the motor buses. One can imagine the relish with which Mr Bamford brought his horse buses back on to Carlton Road, in place of the new-fangled and now discredited motor vehicles. No doubt his drivers told their passengers they had known all along that the motor buses would never catch on. Within a couple of months it was reported that Bamford's service was running at a heavy loss, and was to be reduced to a half-hourly timetable. While all this was going on, local people were keeping a sharp eye on the tram services, and suggesting improvements. In July 1908, for instance, the committee received a letter from the Sneinton Ratepayers' Association, pointing out that a compulsory stop was needed at the comer of Trent Road and Colwick Road, and that a lavatory was required at the terminus.

In its annual report for 1908-9, the Tramways Committee were, as only to be expected, defensive on the subject of the Carlton Road debacle. They conceded that the horse buses were providing a very slow, unattractive service, (an observation likely to have been greeted with a rude gesture from Bamford), and were making a loss of £760 a year. There was, however, a suggestion that the best had been made of a bad job, in the news that two of the motor buses had been converted into tower wagons, for overhead maintenance of the tramway system. 1909, though, brought the prospect of an end to this makeshift state of affairs. The Corporation had, in 1908, obtained Parliamentary authorization to take over powers for a tramway to Carlton; these had been granted in 1902 to the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Tramways Company, as part of a massive plan for 79 route miles. The Notts. and Derbyshire powers had been for a single line only along Carlton Road, so the Corporation sought enlarged powers to enable them to construct a double line. Although this was discussed at the Tramways Committee meeting of April 6th, 1909, the new Bill was not passed until 1910. Officials meanwhile continued to be unobtrusively busy, striving to provide the urinal at the Colwick Crossing terminus. In July 1909 the City Engineer was told to approach the Midland Railway Company or Earl Manvers's agent, in order to obtain a site for this much-needed facility. Land was eventually sold by His Lordship to the Corporation for £14.

At the end of August 1910, work began on laying the Carlton Road track and, on October 4th, the Tramways Committee heard the news they had been eagerly awaiting: the extension was expected to be completed in six weeks, and so Mr Bamford was given two months' notice. It may be conjectured that the parties were, by this time, sick of the sight of each other, and their parting was, regrettably, not to be a harmonious one. On December 16th, the tram route to Thorneywood Lane was opened, a 7½ minute interval service being operated from the Market Place, via Sneinton Market and Carlton Road. On the same day, a service of trams every fifteen minutes was introduced between Colwick Road and the Midland Station. The Carlton Road trams brought about the final, long-delayed, end of horse bus operation over Corporation routes. Two months later, Mr Walters Bamford fired a final salvo, asking the Tramways Committee for 'an allowance', in recognition of the losses sustained by him in running the Carlton Road service from 1908 to 1910. The minutes record that his request was 'not entertained', Mr Bamford thus bowing out of our story on a rancorous note.

Within a few weeks it was reported, on March 3rd, 1911, that lack of custom was resulting in the cutting of the Carlton Road line service to a ten minute frequency. It was noticed at the same committee that the Station Street - Colwick Road trams were, yet again, very poorly patronized, averaging only 4¼ passengers per journey. These were, accordingly, reduced to one car at dinner time each weekday. (This is curious: who, one wonders, would have wished to travel on this route at dinner time, but not at morning or evening peak hours?)

The Nottingham Corporation Bill of 1913 proposed, among other things, tram and bus extensions along Sneinton Road to Sneinton Dale, and motor bus services to Carlton Road and Carlton Hill. The Sneinton Road tramway was, of course, never to become a reality. What did materialize in 1913 was the extension of the Carlton Road tram route from Thorneywood Lane to Standhill Road. Work on this began in September, the public service being introduced on January 5th, 1914, with trams running alternately to the Market Place, or to Colwick Road via Station Street. The new terminus was better sited, from a potential traffic viewpoint, than the Thorneywood Lane one had been, but it was only a temporary railhead, until the line linked Nottingham with the populous district of Carlton. Things were now moving at a rapid pace, and the line was very soon continued down Carlton Hill into Carlton itself. This latest extension saw its first passengers on June 14th, seven weeks after the outbreak of the First World War.

Sneinton's tram system was to remain unchanged throughout the Great War, but one result of the enlarged tramway network was the closure, in July 1916, of intermediate stations on the Nottingham Suburban Railway. Of these, Thorneywood Station now had modern electric trams passing it every few minutes, offering a quick and convenient journey into the city centre. Given this competition, and the prevalent wartime climate of economy, the Suburban Railway, and with it Thorneywood Station, was doomed.

The 1920s were to see the beginnings of a new phase of public transport provision in Nottingham as a whole, and Sneinton in particular. That, however, is a story which must be told at a later date.

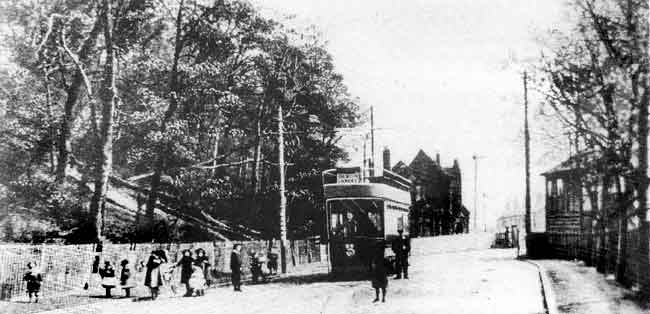

AN EDWARDIAN POSTCARD, published by Hindley of Clumber Street, showing the tram terminus at Colwick Crossing. An interested knot of small children has gathered to watch the photographer.

AN EDWARDIAN POSTCARD, published by Hindley of Clumber Street, showing the tram terminus at Colwick Crossing. An interested knot of small children has gathered to watch the photographer.MY THANKS ARE DUE to the staff at Nottinghamshire Archives Office, and especially to Chris Weir, who helped me find the relevant correspondence files. The photographs are reproduced by courtesy of Nottinghamshire County Council Local Studies Library.

< Previous