< Previous

WRETCHED AND OUT-OF-THE-WAY PREMISES:

The forerunners of Sneinton Library

By Stephen Best

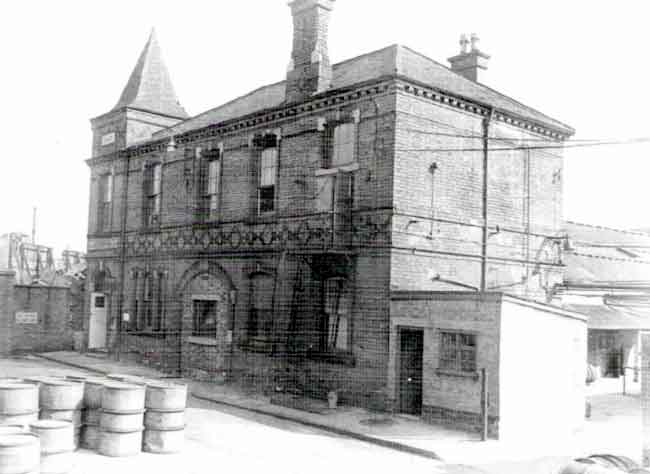

THE FORMER SNEINTON READING ROOM, built in 1867 as the Sneinton Public Offices.

THE FORMER SNEINTON READING ROOM, built in 1867 as the Sneinton Public Offices.A photograph taken in 1960, when the building was part of Boots premises.

FREE NEWSPAPERS have for a number of years been familiar arrivals through the letterbox, their weekly presence on the doormat now being taken for granted. One publication, however, delivered to 5,000 Sneinton homes early in 1929, made just a single appearance. This was The Sneinton Herald', issued to mark the opening of Sneinton Branch Library and Reading Room in Sneinton Boulevard. Though it might be imagined that the 'Herald' ushered in the age of the public library to the neighbourhood, it in fact rang down the curtain on fifty-three years of endeavour in Sneinton, during which, without a proper building, a library service of sorts was offered to residents of the area. It is the background to this first half-century of Sneinton libraries that we now consider, with sidelong glances at the difficulties attending the prolonged gestation of the new library.

The Nottingham Free Library opened in 1868, in premises in Thurland Street now bearing a commemorative plaque. Very soon it had become, in terms of books issued, the fifth largest public library in the United Kingdom. By 1876 some kind of branch provision was clearly desirable, and the March meeting of the Free Public Libraries and Museums Committee addressed the problem. At that time, incidentally, the committee was not made up solely of members of the Town Council, but included such worthies as the Rev. James Matheson, for many years minister at Friar Lane Chapel, and the Rev. Robert Dixon, headmaster of Nottingham High School. It was resolved that a subcommittee arrange to use for library purposes a room in Carter Gate, 'intended to be converted into a Polling Station'. This was now to be furnished as a branch reading room, and supplied with books, periodicals and newspapers. The room was at 35 Carter Gate, next door to the Sinker Makers' Arms public house, and opposite the old burial ground which is now the Ice Stadium car park. This quarter of the town was, in the 1870s, densely built up. The premises at number 35 had formerly been occupied by Henry Fairholm, wheelwright, whose business had moved out to Carlton Road. The Library Sub-Committee formed a set of rules for users of the new branch, which was to be available to anyone over sixteen living in the borough. Opening hours were set at 5-9 pm on weekdays, and 2-9 pm on Saturdays. Tuesdays would be reserved for the use of women only. Perhaps the most striking differences between the services provided at Carter Gate and the present-day public library can be summed up in rules 3 and 4: 'No book, periodical, newspaper or map shall be removed from the room', and: 'No person shall be allowed to remove any book or periodical from the shelves, or newspaper from the stands. Books and periodicals must be received through the Assistant Librarian-in-charge and must be returned to him'. Indeed, Sneinton would have to wait until 1929 for a library offering open access to its shelves, or providing a lending service. For the opening of the Carter Gate branch, the committee decided to buy a dozen Windsor chairs: readers would, after all, be obliged to spend plenty of time on the premises if they were engaged in any kind of extended reading. A good selection of papers and periodicals would be available, including the Graphic, English Mechanic, Punch, Good Words, Chambers', Leisure Hour, Sunday at Home, Cassell's, All the Year Round, Once a Week, and Weekly Welcome. For the additional use of self-improving citizens, Longman's Text Books of Science and Macmillan's Scientific Class Books were also to be housed at Carter Gate. And the librarian-in-charge, through whom all books had to be received and returned to the shelves? This was William Lomas, appointed at a wage of ten shillings per week.

Final details were fixed in July. The legend FREE PUBLIC BRANCH READING ROOM' was to be inscribed on the outside of the building. A clock was needed, and rather than go to the expense of purchasing one, the Free Libraries Committee tried to cadge one from the municipal offices. All was now ready, the 'Nottingham Journal' of July 12th greeting the new library with an expression of high-minded sentiment: There can be no doubt that much good, intellectually and morally, has resulted from the establishment of the Nottingham Free Public Libraries. So that the advantages held forth may be extended, it has been decided to open a branch library and reading room in Carter Gate, to open next Saturday. The room ... is now a light and cheerful one, and has been comfortably furnished.' The paper went on to relate that about 500 books, 'of various classes' would be available, and that the rules in force were ones 'to which no right-minded person will object.' The 'Journal' closed with a clear indication as to the kind of clientele it believed the library would attract: 'We have no doubt that the opening of this branch library and reading room in a populous artizan neighbourhood will be fully appreciated by the working classes.'

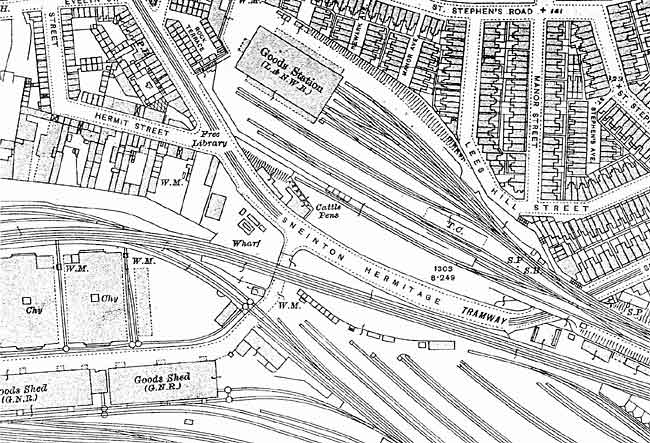

Soon after opening day, July 15th 1876, hours were extended to include mornings. The printed annual report for that year showed that 480 volumes were in stock, and that over the 93 days open to the public, 2073 items had been asked for. Two thirds of these came into the categories of 'Novels, tales, etc.', and 'Magazines and other miscellaneous literature'. The committee minutes record a variety of happenings during 1877. In February, women ceased to enjoy exclusive use of the branch on Tuesday evenings, while a terse entry in June marked what must have been a moment of high drama: 'The Chairman reported that he had given instructions to the Principal Librarian, to summarily dismiss Peter William Lomas for gross insubordination.' Thomas Baxter was appointed in Lomas's place, at 15 shillings a week. Opening hours of the branch were further increased, but by far the most important news concerned the Borough Extension, as a result of which Basford, Bulwell, Lenton, Radford and Sneinton became part of the Borough of Nottingham. In July it was decided that from September 1st, 'the inhabitants of the incorporated districts will be admitted to the privileges of the libraries . . .' This meant, of course, that from now on the Nottingham Free Public Libraries would be serving a much larger, and more widely spread population, and that consideration would have to be given to setting up branch libraries in the 'incorporated districts'. Although the Carter Gate premises were on the edge of Sneinton, they stood within the old borough boundary, and were by no stretch of the imagination convenient for all the residents of Sneinton: they were, too, very small. As it happened, Borough Extension made another building immediately available for library use; one that had certain advantages over the Carter Gate Reading Room. With the transfer of its functions to Nottingham Town Council, the Sneinton Local Government Board ceased to exist. Its responsibilities for the drainage, highways, lighting, street cleaning, slaughterhouses, and other aspects of Sneinton administration having passed to the borough, the local board offices became vacant, and the Free Libraries and Museums Committee could scarcely have been expected to look such a gift horse in the mouth. Despite the fact that, like the Carter Gate room, it stood well away from the built-up centre of Sneinton, it was attractive on account of its much more spacious accommodation. The building, only ten years old at the time, stood in Hermit Street, at its junction with Sneinton Hermitage. Of two storeys, with a modest display of patterned brickwork, it possessed at one corner a little turret, topped by a steep pyramidal roof. Over the door was a stone, engraved 'SNEINTON PUBLIC OFFICES', while a date-stone on the turret proclaimed the date of construction, 1867. Not far to the rear of the premises ran the short Earl Manvers' Canal branch, on the far bank of which were railway sidings and a gasworks. Hermit Street ran from the Hermitage, to join up with Thoresby Street: the thoroughfare was closed sometime after 1941, being thereafter enclosed within Boots premises. The old public offices, not used as a library since 1929, were, at the time the street was closed, in use as Trent Ward Conservative Hall. The building lingered on until the early 1960s, when the site was redeveloped. It stood just about where Spencer's scrapyard in Sneinton Hermitage now adjoins the Boots building.

We have, however, leapt far ahead of our story, and must retrace our steps to 1877. In December that year the committee resolved in principle to use 'the Local Board Room at Sneinton' as a reading room, and two months later it was decided that the Carter Gate room would close, and its books be removed to Hermit Street. Once again the 'Nottingham Journal' commented favourably, on March 8th 1878: 'The great success which has attended the opening of the Free Public Reading Room in Carter Gate, has necessitated its being moved to a more commodious room which has been secured at the late Public Offices in Sneinton. It is double the proportions of the room at Carter Gate, and is within five minutes' walk of it and of the Sneinton Market place.' One feels that the paper stretched the truth a bit here: to get from Sneinton Market to Hermit Street in five minutes would have required a very brisk rate of progress indeed. A couple of weeks later, on March 20th, the Journal was able to report an encouraging response: 'This reading-room is highly appreciated by the inhabitants of Sneinton and the immediate neighbourhood. During last week there was an average daily attendance of 220. The daily average attendance at Carter Gate during the corresponding week of last year was 158.' Thomas Baxter, appointed the previous year in place of the mutinous Lomas, no doubt felt that he was now doing more work, and applied in June for a pay rise. He received an increase of 20%, which raised his weekly wage to 18 shillings. During the winter of 1878-79, Sneinton was one of three reading rooms in Nottingham to be supplied with chess and draughts equipment for the use of the public. This innovation, however, lasted only a few months before the committee 'withdrew the boards, &c., on account of the annoyance caused to the readers'. The mental picture one gains of rowdy chess players in a Victorian library is a diverting one. The printed annual report, after mentioning this storm-in-a-teacup, had to admit that the new reading room was in a 'somewhat isolated situation'. Despite this, the daily average attendance had risen to 353. (It might be mentioned here that the authorities, then and afterwards, were far from consistent in their official terminology for the Hermit Street premises. 'Reading room', 'library', 'branch', and 'room' were all terms used at various times, as they are in the present article).

The 1884-85 annual report reveals few changes in Sneinton reading habits. The collection of books had risen to a still modest 723 volumes. 'Fiction, poetry and drama' and 'Miscellaneous literature' accounted for over three-quarters of the items asked for, followed at a long interval by 'History, biography, geography'. It is surprising to note that the two books described as 'Philology' were issued to the public 84 times - presumably these were dictionaries. The two volumes in the 'Philosophy' class, on the other hand, failed to find a single enquirer. In 1887 there was discussion about moving the branch to Sneinton Market. This came to nothing, as did an offer from a Mr Jones of a site (unspecified in the minutes) for the reading room. Thomas Baxter was still soldiering on at Hermit Street, receiving his reward with the raising of his wages to a pound a week. The following year saw the premises gain (if that be the appropriate word) another railway line as a close neighbour. The sidings beyond the canal behind the reading-room were now rivalled, in terms of noise, by the newly-built London & North Western Railway goods station on the top of the Hermitage rock. Undeterred by these industrial encroachments, the recently arrived vicar of Sneinton, the Rev. F. E. Nugee, began to make use of the library once a week as the venue for mothers' meetings. Still it was recognized that the location was far from ideal, and new sites for the branch were discussed and rejected over the next few months: these included a room in Victoria Buildings, and one in London Road offered by a Mr Hughes. An extension to the opening hours in 1890 gained for the faithful Baxter another increase in pay, bringing his weekly wage up to 22 shillings. One John Starr was appointed relief attendant at 6/6d per week.

Few dramas highlight the passage of the next twenty years at Sneinton Reading Room. Routine matters of maintenance predominate in the committee minutes, with one minor squabble in 1896, when the Corporation's Estates Committee 'declined to clean this room as in former years'. Three years later, a sad little minute logs the death of Thomas Baxter - he is not even accorded a name there, being referred to merely as the attendant-in-charge. He was replaced by his assistant, John Selby, at £1 a week. Selby's first year in charge found the library further dominated by Sneinton's railways. The building of Victoria Station brought with it enormous railway engineering works in Nottingham, including the long blue brick viaduct which was erected along the south side of the Hermitage. A short length of Earl Manvers' Canal was filled in to make way for it.

The inadequacy of library provision at Sneinton aroused official comment in January 1910. A memorandum from the City Council was read at the opening of the Public Library and Museums Committee meeting,. The proposition, headed: 'Sneinton District. Site for Free Library', was moved by Councillor John Henry Gregg, regarded as Sneinton's champion for his constant support of the district's public services. Three years earlier he had been the toast of the area, following the successful outcome of his campaign for an electric tram route to Sneinton. His memorandum is worth quoting at length: 'That in view of the rapid growth of the Sneinton district, and that very few central sites in that locality remain unbuilt upon, the Free Libraries Committee be instructed to secure a site if one can be obtained at a reasonable price, in order that premises for a Reading Room and Library can be erected thereon (when the funds of the Council permit) in place of the wretched and out-of-the-way premises that are now used for this purpose.' It was reported that a site at the junction of Lord Nelson Street and Sneinton Boulevard, suitable for the erection of a branch library, could be obtained for £400, and the committee resolved to enter into a provisional contract for the purchase of this land. Gregg's comments are of interest on two counts - they indicate not only how much dissatisfaction was felt over the shortcomings of the Hermit Street building, but also how rapidly the land off Sneinton Dale was being built up.

THE INCONVENIENT LOCATION of the Hermit Street Reading Room can be seen in this Ordnance Survey plan of 1916.

THE INCONVENIENT LOCATION of the Hermit Street Reading Room can be seen in this Ordnance Survey plan of 1916.Things were not moving quickly enough to satisfy Councillor Gregg, who attended the March committee in person to urge that the Sneinton Boulevard land be bought. He was informed that the committee had made an offer of £400, but that they understood that the land had already been sold for £420. Gregg believed that the site could still be had for £440, and offered to pay the balance of the purchase price if the committee were prepared to pay the £400. One wonders whether the councillor, for all his devotion to Sneinton, would have been willing to stump up the £40 from his own pocket had he known just how long it would be before a new library was eventually built in Sneinton.

In the light of Mr Gregg's strictures, it is revealing to see what the 1910 annual report tells about the use made of the Hermit Street Reading Room, and about the books it contained. We learn that the collection had grown to 1,549 volumes, with 'Poetry, drama and fiction' still the predominant category. There do seem to have been obvious deficiencies: only 33 volumes fell into the 'Useful arts' class, while 'Fine arts' were represented by a paltry thirteen titles. Despite these inadequacies, an average of 363 items were being used each day, and Sneinton clearly deserved a purpose-built library.

During 1910 the committee received letters from Messrs. Eking, Wyles & Morris, solicitors, Long Row, and from a Mr Metcalfe, complaining that rubbish was being dumped on the vacant land in Sneinton Boulevard. The committee could only reply that the land was not theirs, but that they would ask the police to do what they could to stop this practice. Early in 1911, after negotiation with the vendor, the council at last purchased the site for the new library. The following year it was resolved that Nottingham make application for a grant from the Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who financed the building of over 600 public libraries in the British Isles. The council had already sounded Carnegie out on the subject of a new central library, but he had indicated that he felt new branch libraries to be more appropriate for Nottingham. Accordingly, the council asked Mr Carnegie for assistance in providing four new branches. In the meantime, Hermit Street had to be properly maintained, and the minutes for January 12th 1912 duly record the granting of a contract to the Robin Hood Window Cleaning Co. of Forman Street, for attending to the library widows six times each year; the annual cost to be twelve shillings. In their printed report for 1910-11, the Public Libraries and Museums Committee stated their opinion of the motley collection of premises in their care: 'The Committee desire again to call the serious attention of the Council to the urgent necessity for providing suitable buildings to be used as Branch Libraries and Reading Rooms in the place of some of the buildings now in use for that purpose. Several of the present buildings were rented by the Committee as a temporary expedient and to ascertain the requirements of the various districts in which they are situate. They are inconvenient, lacking in accommodation, and totally inadequate to supply the needs of the localities they serve. The Committee strongly recommend that four new Branch Libraries and Reading Rooms should be erected on the lines of those at Hyson Green and Carlton Road, on suitable sites at Bulwell, Basford, Sneinton, and the Meadows.' The plight of the library service in Sneinton could scarcely have been more clearly set out. At least the committee were able to report that they had, during the year under review, definitely acquired the land for a new branch here.

1913 saw the receipt of a further letter from the firm of solicitors (by then Eking, Morris & Armitage), complaining this time that the library land in Sneinton Boulevard was 'being used by youths as a football and playground', and should be enclosed. We now enter on a long-running story, with what seem, in retrospect, quite hilarious attempts on the part of the committee to make the site pay its way until the new library should be built. The reader is asked to be patient while all the pettifogging details of the next decade or so unfold: they do, at least, provide a glimpse of the 'nuts-and-bolts' problems which beset council committees. The City Architect worked out the cost of fencing the land - £13 or £14, but the committee, jibbing at such at outlay, resolved to ask bill posting firms whether they would be willing to fence the site 'for the purpose of a hoarding station'. The companies were not interested, so the City Architect was instructed to approach them again, with complicated schemes of sharing the cost of a hoarding, and proposals for a sliding scale of rents. Nothing came of this suggestion, either. Good news, however, came from Andrew Carnegie's secretary: under certain conditions Carnegie was willing to grant £15,000 towards the erection of four new branch libraries. This was very satisfactory to the council, the Town Clerk being asked to write, thanking Carnegie for his generosity. Christmas Week, 1913, brought yet another tiresome letter from Eking, Morris and Armitage: owners of properties adjacent to the new library site were still suffering 'nuisance', through the lack of a fence. Enough was enough: the committee decided to take action, accepting Huskinson & Son's tender of 4/9d per yard for fencing. One can well imagine their exasperation on hearing, eight months later, that employees of the Universal Bill Posting Co. were 'climbing the newly erected fence, and trespassing upon this land for the purpose of posting bills on adjoining property.' The Town Clerk was ordered to deal with this: like us, he was doubtless wondering when this farce was going to end.

The outbreak of the Great War put an end, for the time being, to progress in the library service. Realising that the prospect of new libraries had receded into the distance, the committee resolved in September 1915 that their existing branch reading rooms 'be colorwashed and whitewashed and thoroughly cleaned up.' However, economy was in the air, and with male members of staff being called up for military service, branch reading rooms were, from May 1916, closed between 2 and 5 pm during the summer. The following January saw a decision to close branches between 2 and 3 all the year round, for the duration of hostilities. For the first time for almost half a century, Nottingham now had a new chief librarian. John Potter Briscoe, who had been in office for 47 years, resigned at the end of 1916, and was succeeded by his deputy, Walter A. Briscoe, who also happened to be his son. Such a succession would be unlikely to occur today without considerable public comment.

With the advent of peace, the committee recognised that the £15,000 granted to them in 1913 would now not go nearly as far as it would have done six years earlier. In the summer of 1919, accordingly, the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust was asked to increase its grant. The Trust replied that as all building operations, with the exception of urgently needed housing, were being deferred, consideration of the grant would have to stand over for the time being. Meanwhile, the community was still trying to get the best use out of the Hermit Street room, the local branch of the National Union of Railwaymen obtaining permission to hold meetings there in the evenings at a fee of 6/- a time. In some quarters, evidently, it was felt that the new library would never materialize: in 1920 the Nottingham Cooperative Society enquired whether the committee would sell the land at the corner of Lord Nelson Street and Sneinton Boulevard. The committee refused, but raised yet again the hoary question of drumming up advertising revenue from the site. With undiminished optimism they instructed the Town Clerk to approach the Universal Bill Posting Co. and Messrs. Rockleys Ltd., to find out whether they would pay for hoardings, and rent the space from the council. This evidently came to nothing, and two months later James Stott of Colwick Road wrote to ask if the site was for sale. Stung into further action, the committee made yet another approach to the bill posters, offering a short-term tenancy. Rockleys turned the proposition down flat, while the Universal were interested only if guaranteed five years' tenancy. Typically, the committee made niggling objections to this, suggesting a 2-year period initially, to be renewed annually thereafter. By this time, Stott had re-entered the lists, offering to rent the land as a coal yard. He was prepared to pay £50 rent per year plus rates. No sooner had the committee agreed to this than Stott demanded a ten year lease. The committee offered five - the very period they had a year earlier refused to the Universal Bill Posting Co. With incredible, if misguided, pertinacity, they now proposed to get in touch yet again with the bill posters, to discuss a 5 year tenancy, with optional yearly extensions. Presumably they were hoping for a better offer than Stott's £50 a year. In September 1923, however, Stott wrote to say he was now interested only in buying the freehold of the site. The committee decided to take no further action. They had, after more than a decade's dithering, yet to make a penny from this site, and one can only observe that it served them right. In 1924 some small consolation was offered by a Mr Butlin, who wrote to ask if he could rent a corner of the site (at the bottom of Lord Nelson Street) for his tailor's hut.

While attention at Sneinton had been focused on the task of selling advertising space at the vacant library site, matters elsewhere in the city had been progressing more satisfactorily. The first of the four new branches envisaged in 1912 was opened at Bulwell in February 1924: money for this was provided by the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, with a further generous contribution from the local Miners' Welfare Committee. In March 1925 the Meadows got its new library, funds for its erection being given by the C.U.K.T. Plans were also well advanced for new branches at Lenton Boulevard and Basford, for each of which the Miners' Welfare Committee was providing a substantial grant. Sneinton and its representatives evidently felt that their district's library service was being left in a backwater, and was, perhaps, suffering from the lack of a powerful pressure group in the neighbourhood.

1925 saw the issue raised again. At the May committee Councillor Bury asked a question 'as to the possibility of the erection of a Branch Library for Sneinton District,' and the following month found six members of the Sneinton Parents' Association, with Councillors Lokes and Green, appearing as a deputation before the committee. They urged the construction 'at a very early date', of a branch library on the land purchased 'many years ago'. Councillor Jackson, vice-chairman of the committee, thanked the deputation for the courtesy with which they had put their case. Inevitably, discussion of the matter was adjourned for the time being. Local people, however, were now in no mood to let the matter drop, and in October 1925 the committee received a letter from the honorary secretary of the Sneinton Parents' Association, asking whether a decision had yet been arrived at. In response to this, the City Librarian, Walter Briscoe, was requested to look into the provision of a temporary library building on the site. Early in 1926 Briscoe recommended that a temporary building would not be appropriate, and that the committee wait until the new libraries at Basford and Lenton Boulevard were open. A permanent library for Sneinton could then be considered. After estimates of the likely costs of temporary and permanent buildings had been prepared by the City Engineer, the committee agreed to follow the City Librarian's advice.

In February 1927, the committee visited Sneinton to examine the likely site for the library. The eastward spread of the area prompted them to look, in addition, at vacant land on the corner of Port Arthur Road and Sneinton Boulevard. They were also told of available sites in Meadow Lane (a non-starter, surely, if a central location was desired) and Sneinton Dale. The committee, however, preferred the site they already had, at the Sneinton Boulevard/Lord Nelson Street corner: after sitting on it for so long, they could hardly have said anything else. The City Engineer, T. Wallis Gordon (designer of the War Memorial Arch on the Embankment), pointed out that if accommodation equal to that at Lenton Boulevard and Basford was required, the limitations of the site would dictate a two-storey library at Sneinton. Gordon was asked to submit designs for the branch, and quickly estimated the cost, including furniture, fittings, and street works, at £9,520. Meanwhile the Digby Colliery Company had been approached for a grant towards the new branch, replying that though they were unable to make a direct contribution, they would 'heartily support and recommend the scheme to the appropriate Miners' Welfare Committee.' This organisation, however, was not prepared to help on this occasion, and the Carnegie grant having been used for the four post-war branches already built, the City Council found itself obliged to finance the new Sneinton Branch Library in its entirety.

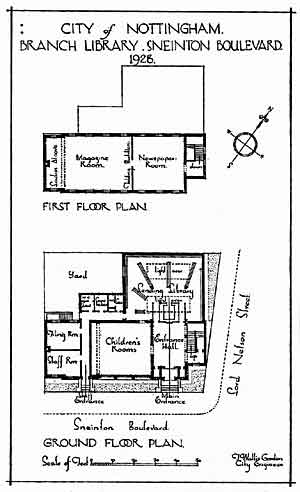

PLANS FOR THE NEW BRANCH LIBRARY, from the booklet printed for the laying of the foundation stone.

PLANS FOR THE NEW BRANCH LIBRARY, from the booklet printed for the laying of the foundation stone.The job was put out to tender, and awarded to Frank S. Kennewell, builder, of Wilford Grove, whose price of £7,744 was the lowest. The highest tender was that of Simms, Son & Cooke, at £8,480, other well-known firms submitting tenders including Thomas Long & Sons, Thomas Fish & Sons, Thomas Bow, and Gilbert and Hall. There were, briefly, problems over the siting of the projected emergency exit, as the owner-occupier of adjacent premises, with what sounds like perfectly reasonable obduracy, 'would not grant right of way through her back yard'. All having been sorted out, the date of the foundation stone laying was fixed for February 14th 1928, at 3 pm. A commemorative booklet was printed for the occasion, and distributed to guests. The leaflet included plans of each floor of the new library, which was described in detail, with much emphasis on its high quality. 'The whole of the furnishings and fittings will be on the most modern lines. Each room will have an abundance of light and ventilation, and be heated by a low-pressure hot water system. The whole of the public rooms will be laid with wood block flooring, the object being to preserve as much quietude as possible; and the entrance-hall paved with marble terrazo [sic]. Regarding the exterior, the elevation and details will be classic in character. The dressings of Derbyshire stone will be in rich contrast to the brick facings, and the colour scheme will be both pleasing and attractive.'

The 'Nottingham Journal' reported the stone laying in some detail. Alderman Foulds, chairman of the committee, stressed the financial difficulties surrounding the building of this branch library. He regretted that the absence of help from the Carnegie Trust or the Miners' Welfare Committee meant that Sneinton Library would cost the Corporation as much as the four previous branches put together. He hoped that the library would give much satisfaction to Sneinton; if people showed as much appreciation as they had in the other four districts, 'the committee would feel repaid for their labours'. The architect, T. Wallis Gordon, then handed a silver trowel to the Mayor, Alderman Huntsman, who was to perform the ceremony. After prayers by the Rev. Arthur Briggs, minister of the Albion Chapel, the Mayor addressed the assembled guests. He remarked that Sneinton 'Had made its needs vocal on the subject of that library, and every member of the committee rejoiced that they were able to start upon the erection of the building. Not so long ago, a library such as would be housed there was a privilege of the very few.' Other civic worthies vied with each other in flowery tributes to the public library movement. To the Sheriff, Alderman Pollard, a library represented 'medicine to the mind', while Councillor Edlin, not to be outdone in eloquence, chose to describe the library as 'the open sesame to the gates of knowledge'. Invited visitors then trooped off to the Guildhall for tea. More speeches were made here, Mr H. McCaig, master-incharge at Sneinton Boulevard School, assuring the authorities that they would get enthusiastic support 'from the schoolmasters and mistresses of Sneinton in interesting the children in the library.'

The committee minutes report good progress throughout 1928 in the construction of the library. Local residents, long used to the familiar bit of open ground at the corner of Sneinton Boulevard and Lord Nelson Street, saw the building rapidly take shape. In January 1929 the work was almost finished, and an opening ceremony was arranged for March. The 5th was originally chosen, but the event was later put back for one week. The Lord Mayor was to perform the official opening, (his office having been raised in dignity from Mayor since the foundation stone laying), while the Sheriff would support him. As we learned at the beginning of this account, 5,000 copies of 'The Sneinton Herald' were to be printed and delivered locally. Staffing matters were also settled. Miss Violet Keywood, librarian-in-charge at Basford Library, was to be transferred to Sneinton to run the new branch, while Charles Bostock would move from the Hermit Street premises, to be reading room attendant at Sneinton Boulevard. James Keetley was appointed assistant reading room attendant and cleaner at a minimum weekly wage of £2.5.0d. His pay would be increased according to the work required of him. An 'assistant librarian (female)' was also to be engaged.

So we have returned to our starting point, with 'The Sneinton Herald' plopping through the letter boxes of the neighbourhood. Prominent on its front page was a photograph of Ald. Huntsman, resplendent in mayoral robes, posed in the act of passing his trowel over the foundation stone a year before. The features of the new library were eulogized: from the 'spacious entrance hall', a staircase led to the newspaper and magazine room on the first floor. 'This', we read, 'will be a large Reading Room, 65 feet long by 25 feet wide, divided by a glass screen into two sections; the first as a newsroom, and the second as a magazine and general reference room, with special provision for lady readers.' The plan duly showed a 'ladies' alcove' at the far end of the room. The lending library on the ground floor was 'Planned on the open-access system', its book racks 'radiating and under full view of the Librarian-in-charge.' The room for boys and girls was hailed as 'another important feature'. All of this may sound commonplace enough to anyone familiar with the services offered by public libraries in 1991. It must be remembered though, that this was the first time Sneinton had had a public lending library; the first time that library users here were to be able to browse among the shelves, rather than ask for a title at the counter; and the first time there had been any library provision in Sneinton for children. No wonder the authorities were determined to mark the occasion with a flourish. The 'Herald' also featured portraits of Alderman Albert Atkey, the Lord Mayor, and Alderman William Green, the Sheriff, principal actors in the opening ceremony. One cannot help thinking, though, that most Sneinton people needed no photograph to help them recognise Billy Green, probably the best-known public figure in the district.

The 'Herald' was probably financed by the inclusion of advertisements of local traders, such as Mosley's Cycle and Gramophone Depot, 196 Colwick Road - 'Cycle time is coming, now for the open road'; and Galpin's Stores, 56 Sneinton Hermitage - 'Our prices for your household requisites are among the lowest in Sneinton'.

Opening day, March 12th 1929, found a reporter and a photographer from the 'Nottingham Journal' on hand to cover the proceedings. The following morning's paper accorded the event a three-decker headline:

WHERE NOTTINGHAM LEADS.

RECORD CREATED IN BRANCH LIBRARIES.

BOON FOR SNEINTON.'

The report began by commenting on the size of the crowd present to witness the opening of the library. A photograph attests to the degree of public interest, a densely packed assemblage of onlookers spilling into the roadway at the corner of Sneinton Boulevard and Lord Nelson Street. All wear hats: cloth caps, bowlers, homburgs, trilbies, cloche hats, together with policemen's helmets and an official's peaked cap. One local, in cap and muffler, stands with hands in pockets, regarding the camera with the air of a man not easily impressed by anything, let alone a library. His beautifully polished boots are worthy of notice. Ald. Foulds, still chairman of the committee, hoped that the branch, having been built entirely out of ratepayers' money, would be well used by Sneinton people. He referred to the delay in building the library since purchase of the land 'twenty three years ago'. The period had in fact been 18 years, long enough in all conscience, but not quite as bad as the alderman stated. 'But', continued Mr. Foulds, 'at last it had come, and a very beautiful library it was.' The reading room and lending library for adults would be open immediately the official proceedings were completed, and the room for boys and girls would be ready for use in a week's time. Alderman Atkey, in his speech, recalled that when he was a young man, the Central Reference Library was the only one affording opportunities for self-education to the young people of Nottingham. The results of an enterprise of this character, continued the Lord Mayor, could not be termed in £.s.d. 'Where they were investing in the future of the human race it was difficult to encompass the dividend that would accrue.' Ald. Atkey's prose style was a touch convoluted, but his heart seems to have been in the right place. The Sheriff proposed a vote of thanks to the Lord Mayor, a warm tribute was paid to Mr. Gordon, and the doors were thrown open. The assembled crowds entered the library, anxious, no doubt, to erase the memory of half a century of inadequate library provision at Hermit Street.

Sneinton's library history since 1929 must be left for another hand to write, so we end with a brief postscript. The old Sneinton Reading Room, abandoned without regret by library staff and users alike, was, as already related, to survive in a variety of guises for over thirty years before its eventual disappearance. The new library quickly showed its value. The 1928-29 annual report of the Public Libraries and Museums Committee was written only a week or two after its opening, but the authorities were already confident that they had a winner: 'All the departments have opened with the promise of every success, and it is evident that the Committee's latest extension will be a social as well as an educational asset to a well-populated district . .' A year later the committee was able to report that 77,246 books had been borrowed from Sneinton Library in its first twelve months. The new building had indeed been a very long time in coming, but the community had acquired an amenity well worth waiting for.

OPENING DAY at Sneinton Branch Library, March 12th 1929. Beyond the onlookers, an interesting variety of wheeled vehicles may be seen in Lord Nelson Street.

OPENING DAY at Sneinton Branch Library, March 12th 1929. Beyond the onlookers, an interesting variety of wheeled vehicles may be seen in Lord Nelson Street.MY THANKS ARE DUE to the following for allowing me access to committee minutes, printed annual reports, and local newspapers: Nottinghamshire Archives Office, Nottingham University Department of Manuscripts, and the Local Studies Library, County Library, Angel Row (by courtesy of whom the photographs are reproduced).

< Previous