< Previous

'BY CRUEL HANDS':

The strange death of John Wainman

By Stephen Best

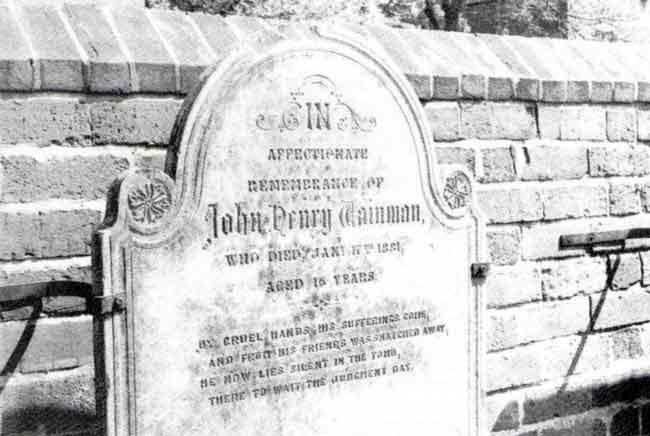

JOHN WAINMAN'S GRAVESTONE, now re-erected close to the boundary wall of Sneinton churchyard.

JOHN WAINMAN'S GRAVESTONE, now re-erected close to the boundary wall of Sneinton churchyard.THIS IS A VICTORIAN TRAGEDY, whose central character became, posthumously, a nine days wonder. On the vast canvas of nineteenth century England, the episode may have made only a tiny mark, but it came as a crowning disaster for a woman who can have enjoyed few of life's advantages. For a few days early in 1881, the death of a Sneinton boy commanded the attention of newspapers far away from Nottingham, even The Times noting the strange and unlucky way in which he met his end.

The story was stumbled upon - almost literally - by chance, and we begin with its postscript, a gravestone in Sneinton churchyard. Several years ago, before restoration work was carried out, a number of headstones lay flat on the grass, just inside the Dale Street gate. A friend one day mentioned that one of the stones bore a curious inscription, and wondered whether there might be a story awaiting discovery. This is what was carved there:

'In affectionate remembrance of John Henry Wainman,

who died Jany 17th 1881. Aged 16 years

By cruel hands his sufferings come,

And from his friends was snatched away.

He now lies silent in the tomb,

There to wait the judgment day’.

This certainly looked intriguing, but an examination of inquest reports for that week in the Nottingham press drew a blank, and the Wainman gravestone was added to the list of Sneinton puzzles to be look at when time allowed. Then, as part of the churchyard renovation, the stones lying flat were moved to an upright position by the boundary wall, and it was while photographing their inscriptions that I was again struck by the enigmatic nature of John Wainman's epitaph. On the off-chance, the Sneinton burial registers were consulted, and there, in the not very legible hand of the curate, the Rev. J. W. Townroe1, lay the key to the mystery. Under the date of burial, January 25 1881, Mr Townroe had written 'Coroner's inquest', and below the boy's Sneinton address had added the words 'Reformatory, Surrey'.

An inquiry of Surrey Record Office revealed the existence there of coroner's vouchers, itemising expenses incurred in holding inquests. Among these was a voucher for £5.11.0d for the expenses of George Hull in conducting an inquest on John Henry Wainman at Redhill, Surrey, on January 20 and 24 1881. That it took place at Redhill made it likely that the reformatory mentioned in the burial register was the Philanthropic Society's Farm School at that town, and indeed the admissions register of the institution recorded that the boy entered the school on November 24 1877. From this point it was necessary to trace how he came to be at Redhill, and to piece together the background to his life in Sneinton and at the school. Here, sadly incomplete, but embodying the facts it has been possible to uncover, is John Wainman's story.

He was born at Walker Street, Sneinton, on November 6 1864, the only child of John Wainman, a labourer, and his wife Charlotte, formerly Cross. John Wainman, senior, was unable to write: when informing the registrar of his son’s birth, he made his mark with an 'X', rather than signing the document. The birth was not registered until December 18, 42 days after John's arrival in the world, and the last day of the six weeks period during which the registration had to be made. This was also the day of the baby's baptism at Hockley Chapel, at that date a Primitive Methodist place of worship. The chapel building, situated between nos. 50-60 Goose Gate, survives today as premises of the Nottingham Sewing Machine Company. Although he was usually referred to later in life as John Henry, the child's name appeared simply as John on the birth certificate.

When John Wainman was only three, a calamity struck the family. The boy's father died on July 20 1868, of cholera, having been ill for only sixteen hours. His death occurred at Langley Mill, just over the Derbyshire border, his occupation being given as 'general labourer'. It cannot be said with certainty what work he was engaged in: Langley Mill at that date was a centre of brick manufacture, lime burning, sinker making, and corn milling by steam. It is likely that John Wainman, senior, lodged at Langley Mill during the working week: it would have been possible for him to travel from Nottingham each day by the Midland Railway, but considerations of time and money no doubt ruled this out. The death was reported to the authorities by John Knight of Langley Mill: a man of this name was listed in the 1868 directory as a beer-seller. John Wainman was 37 years old, and was buried in Sneinton churchyard on July 23, the service conducted by the curate, the Rev. John Riley.

Young John attended the boys' section of the National School (the Church School) at Sneinton: this is the Old School Hall building, close by the windmill, and now used for community activities. Unfortunately, no records survive from his years at the school, so we do not know what impression, if any, he made on his teachers. The 1871 census shows the little family resident at 1 Portland Place, Walker Street. Listed were John, then aged six, his mother Charlotte, 42, described as a hosiery mender, and an 18 year old boarder, a framework knitter named Henry Sharp. The building of Walker Street had begun only about 1830, so the street was barely 40 years old. It was, however, a poor quarter, like much of New Sneinton, with numerous courts and yards hidden behind it. Portland Place lay on the right-hand side as one went up the hill, between Haywood Street and Upper Eldon Street. Reached through a tunnel entrance under a house fronting on to the street, it contained five houses of back-to-back type, looking out over a small yard. Money was rarely plentiful hereabouts, and the lodger's contribution may have been crucial in helping to make ends meet.

Our next glimpse of John Wainman is not a happy one: it comes through the columns of the Nottingham Daily Express of Tuesday, October 23 1877. Under the heading: 'Borough Police Report', the following paragraph appears:

SINGULAR CONDUCT OF A YOUTH - John Wainman, aged 13, was charged with committing felonies. Inspector Gibson, of the County Police, stated that the prisoner's mother took the boy to the Shire Hall on Saturday and informed him that he had disposed of a new suit of clothes and also stolen 4s. from the house of Mrs Rice, in Broad Marsh, on Sunday, October 14th. Prisoner, in answer to the charge, stated that a man named Glenn, who lived in Glasshouse Street, had got the money, and witness on going to that address found a cup in Glenn's possession which had been stolen from Mrs Rice's house at the time the money was. Prisoner now alleged that it was Glenn who took his new suit and pledged it for 10s.6d., and he was also concerned in stealing the money. The Bench remanded Prisoner until Thursday.'

The Nottingham Journal report was in most respects identical, but gave the added detail that the four shillings stolen from Mrs Rice was found in the cup at Glenn's house. Quite what the shadowy Glenn's role in all this had been is not clear. At all events, he is not mentioned again in the proceedings against John Wainman. It all looks very much as though Mrs Wainman was at her wit's end in trying to control her son, who was, despite the newspaper story, still only twelve. No doubt the purchase of new clothes for him had been a financial sacrifice for her, and John's pawning of these had been the last straw. The fact that she gave him in charge suggests that she was desperate.

John Wainman made a further appearance in court on October 25 1877: the magistrates of the previous Monday, Messrs. Evans and Ball, had been joined by Mr Forman. The Nottingham Daily Express of October 26 reported thus: 'A YOUNG THIEF - John Wainman. a boy, was charged with stealing 4s., the property of Jane Rice, of Broad Marsh. Inspector Gibson said the boy was brought to him at the Shire Hall by his mother, who accused him of selling his clothes. It appeared that he had also gone to the house of his aunt, in Broad Marsh, and taken 4s. away, and it was also proved that he had stolen drink. Prisoner admitted that he had been convicted of felony before, and sentenced to seven days' hard labour, and the Bench sent him to gaol for a month, and to a reformatory for five years subsequently'.

Several features of interest appear here. Although the disposal of his clothes for cash had clearly been a dishonest act, John was charged only with the theft of the money and, perhaps significantly, drink. It is of course possible that he had taken this to sell, rather than to consume - in the absence of relevant court records, one can only conjecture. The fact that Mrs Rice was the boy's aunt must have been an added embarrassment for poor Mrs Wainman. John's previous conviction must also have weighed heavily with the magistrates - once again, there are no court records giving information about this, consequently I have been unable to trace further details - and they were not disposed to treat him leniently. So he vanished for ever from his job as errand boy at a local warehouse, to start his month's sentence at Nottingham Borough Gaol.

John Wainman's prison sentence began on October 25 1877, twelve days before his thirteenth birthday. Thirty days later, on November 24, he was admitted to the Philanthropic Society's Farm School at Redhill, Surrey, where he was destined to spend the rest of his life. A word should here be said about the school and its aims. The Philanthropic Society (now the Royal Philanthropic Society) had been founded in London in 1788 by a group of gentlemen greatly concerned about the large numbers of homeless children in the capital, able to make a living only by begging or crime. At first the Society maintained 'families' of children, looked after and trained by craftsmen and their wives, in separate houses. In 1792 an institution was opened in Southwark for the children of convicts, and for boys and girls who had committed criminal offences. In 1802 a separate Reform' was established for the boy offenders and the main institution was afterwards known as the Manufactory': its boys were chiefly occupied in making clothes, shoes, rope, and other products. There was also a Female Reform, adjacent but totally segregated. During the 1840s important changes took place. The Female Reform was closed down, convicts' children were no longer admitted, and the decision was taken to move the institution from South London to the country. An estate was accordingly bought at Redhill, and new buildings designed and erected. The move to Surrey took place in 1849.

The Philanthropic Society's Farm School, to give its new name, was set up on the house system, a master and his wife teaching and supervising the sixty or so boys in each of three houses. By the time of John Wainman's arrival at the school, there were five houses on the estate. At this period the establishment was classed as a reformatory, most of its boys being committed by magistrates, and paid for by the relevant authorities. As the name suggests, farm work was the main occupation, though instruction was also given in other trades, such as tailoring and carpentry. The aim of the committee was 'to assimilate as far as the diverse conditions permit, the life and administration of the school to that of the great public schools of England.'

So John Wainman arrived, and from the school's admissions register we gain our only physical description of him. A vivid picture emerges, and I confess to finding it a haunting one. All at once one is made to realise that the slate headstone in Sneinton churchyard is more than a piece of local history, that it represents (as do gravestones everywhere) a unique human being. Though his exploits in Nottingham might have given the impression that he was a fairly hard case, one learns with surprise that John was still a very little boy indeed. He was, states the register, just 4 feet 9½ inches in height, with fresh complexion, dark brown hair, straight nose, and 'an ordinary figure'.

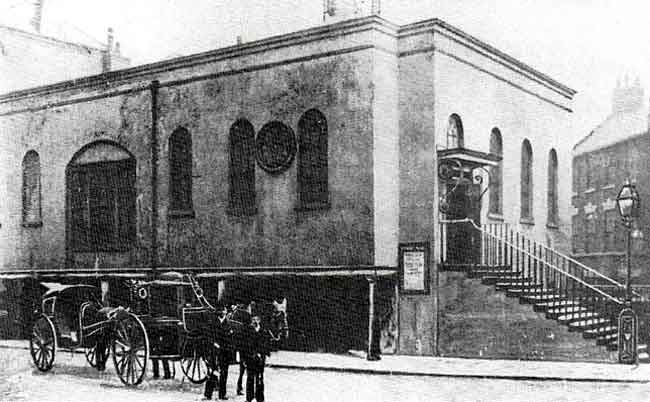

THE OLD GUILDHALL AND PRISON, Weekday Cross, where John Wainman was sentenced in 1877 to five years at a reformatory. The Nottingham Borough Police Court had been moved here in 1873.

THE OLD GUILDHALL AND PRISON, Weekday Cross, where John Wainman was sentenced in 1877 to five years at a reformatory. The Nottingham Borough Police Court had been moved here in 1873.(Picture: courtesy Nottinghamshire County Council Local Studies Library).

He had a full, round face, a scar on his left hand, small lobes to his ears, and grey eyes set well apart. Mrs Wainman, having by now given up the mending of hosiery, was described in the admissions register as 'a washerwoman of good character in poor circumstances'. Though an only child. John Wainman had several aunts and uncles in and around Nottingham. We have heard before of Mrs Rice, whose late husband, Clement, had been a basketmaker. In Sneinton were Daniel Wainman, a brewer, of Smith's Place, Pierrepont Street, and a Mrs Thurman of Walker Street, while further afield were John Knight2, coal dealer, of Bailey Street, and William Wainman, labourer, of Fishpool, near Mansfield.

We come now to John's death on January 17 1881, and to its sensational aftermath. To the world at large the news was broken by the Mid-Surrey Mirror of January 22, in a report headed: SHOCKING DEATH AT THE PHILANTHROPIC FARM SCHOOLS'. On Thursday, January 20, the coroner, Mr Hull, had held an enquiry into the death of John Henry Wainman, 'an inmate' of the school. It was stated that the boy had been in the care of the medical officer from January 12 until his death five days later. The day before he died, he had made a statement before the Mayor of Reigate, declaring that he had, on January 10, been injured by three fellow inmates. It was reported that this statement had been made in the knowledge that he was dying, and that, 'He was quite sensible to the last; and though wandering a little, he was perfectly conscious to the last, and he understood the purport of the questions.' The inquest was adjourned to the following Monday, the coroner observing that it seemed to be a serious case, and would need careful enquiry. The three other boys were charged, and placed in custody.

Having thus far described the proceedings in formal fashion, the newspaper lapsed into gossip: 'It is rumoured that the deceased met with his death by having a rope placed round his body, and having been drawn to the top of the pole of a 'giant's stride', something occurring to distract his persecutors' attention, the rope was released, and the boy fell violently on his shoulder to the ground'. The MidSurrey Mirror went on to report that, despite his injury, John Wainman had gone out to work that afternoon. On the following day he was noticed with his coat off, and on medical advice was sent to the infirmary at the school. He grew gradually weaker, until his condition became so grave that he made his deathbed statement before the mayor. On Monday night John had died. 'He seems', said the paper, 'to have provoked the ire of the members of Gurney's, to which house he, together with the three boys above referred to, belonged.' The fact that this 'rumour' was in most respects accurate does not, one feels, excuse the reporter for indulging in tittle-tattle.

On January 22, John Wainman's death was reported to the management committee of the Philanthropic Society School by its resident chaplain, the Rev. Charles Walters, principal officer at the school. This was the day on which Mrs Charlotte Wainman, who had been present at her son's deathbed, took his body back home to Nottingham, having declined to allow his burial at Redhill. Although the hearing of January 20 had been held at the school, the adjourned inquest four days later took place at a nearby hotel, 'to suit the convenience of the jury.' It was reported in the Mid-Surrey Mirror under the headline: 'THE PHILANTHROPIC ACCIDENT. William Hearne, master-in-charge of Gurney's house at the school, gave a full and clear account. He began with some information on the three boys concerned in John's injury. Of these, Charles Wyatt was 'one of the best boys I ever had'; Horace Golding 'ran away some time ago, but his return was almost voluntary'; while William Smith had 'conducted himself satisfactorily since his return, about five weeks ago.' The latter had left the institution for some eight months, but had been brought back. Mr Hearne stated that he was sitting at his desk in the schoolroom about 12.45 pm on the day of the incident. The boys, having had their dinner, were in the playground. On hearing a cry, he had gone to the door, to see thirty boys or so around the circle pole, from which John Wainman was suspended by a rope under his arms, his feet about a yard off the ground. The master called out to the boys to release John, and 'Almost before I had spoken his feet struck the ground; his shoulder pitched against the circle pole, then he rolled on to the ground, and the boys scampered away, and in the rush one or two fell over him.' Hearne further deposed that John got up unaided, and came into the schoolroom, where he remained for a quarter of an hour. He did not complain of being hurt, and worked as usual the following morning. After dinner on Tuesday, Mr Hearne noticed the lad in the schoolroom with his jacket off, while other boys looked at his shoulder. In reply to his question, a boy replied, 'O, Wainman has hurt his shoulder, sir!' Hearne observed a swelling and sent John to bed. Here he remained until Wednesday evening, when on being told that the shoulder was no better, the master sent the boy to see the doctor. John Wainman was able to walk there and back, and ate his dinner afterwards. On being questioned more closely about the playground incident, Mr Hearne remarked that 'It seemed that rough play was going on with laughter.' He had never heard Wyatt, Golding, or Smith make any threats against John, and added that no more than half a minute had elapsed between his hearing John cry out, and the lad being back on the ground. It was, he said, a common thing for the boys to get half way up the pole, a height of seven or eight feet. (Here, perhaps, one ought to give some idea of what the circle pole, or giant's stride, looked like -even in 1881 not everyone knew what it was, and Mr Hearne was asked, at a later hearing, to describe this piece of playground equipment. He said that it was a six-sided piece of wood, about fifteen feet high, with pegs of wood, similar to the rungs of a ladder, projecting about seven inches from each side. These formed steps, by which the pole could be climbed).

The next witness was James Carter, a fellowinmate of Gurney's. At 12.45 on January 17 he was looking out from the schoolroom door, when he saw Golding and Smith take John Wainman from the wash-house to the circle pole: there they put a piece of rope round his waist, under his arms. Golding then fixed the rope to the top of the pole, and Smith pulled John up 3 or 4 feet from the ground, Wyatt hitting him three or four times with a piece of cord. Carter stated that no one had interfered, and that it did not strike him that there was any danger. Unlike Mr Hearne, he thought that the boys were not laughing. He added that he, too, had never heard Golding or Smith threaten John, who, he believed, went willingly with them.

Next to give evidence was Mr W. A. Berridge, medical practitioner of Redhill, acting for his partner Mr Hallowes, surgeon to the school. Berridge had examined John Wainman on Wednesday evening, finding 'signs of an obscure injury to the shoulder'.

He had put on bandages and a pad, but had found no other signs of violence. Without asking the boy the cause of the injury, he sent him to the infirmary. On Friday he again saw John, who was by this time very ill, with inflammation of the lung. After his death an examination revealed that the boy had been well nourished, but that there was a good deal of swelling of the right shoulder and arm, with discolouration. There were traces of bruising in the pectoral muscle: beneath this was 'a collection of matter', and there was 'a fracture of the coracoid process of the scapula - a very unusual fracture - a piece of bone being broken off deep in the shoulder blade'. There was acute inflammation of both lungs, and the cause of death was pyaemic inflammation of the lung, secondary to the injury. (As a layman I found all this difficult to understand, and sought clarification: this is what I was told. The coracoid process is a tiny bone, shaped like a crow's beak, which is attached to the shoulder blade. A piece of the boy's coracoid process had broken off, piercing the lung and causing the fatal inflammation. Pyaemia is blood poisoning caused by pus-forming micro-organisms in the blood. My informant had, in his professional experience, never heard of such an injury to the coracoid process. John Wainman was evidently very unlucky indeed).

After the magistrates had finished with the doctor, John Jeffries, another inmate of Gurney's house, gave his version of events. His account tallied closely with that of James Carter, but he added that he had never seen 'such play before, though they sometimes played in a rough sort of way.' Jeffries had taken it for play in this instance and, like the other witness, knew of no quarrel between the boys concerned. He claimed that John Wainman did not ask to be let go, but 'kicked about', and he confirmed that John had fallen against one of the pegs sticking out from the circle pole.

The coroner then summed up, and one is immediately struck by the good sense of his remarks. The jury, he said, 'would have to dismiss from their minds the character of these boys: they must have their games as well as other boys, and the affair might have occurred to a gentleman's son in any large public school3 in the country'.

The question was, said Mr Hull, whether the boys were merely indulging in rough play, or whether sufficient malice had been shown to justify a manslaughter verdict. He reminded the jury of the rarity of such an injury as John had suffered, which might 'never again occur in a man's lifetime'. After a brief interval, a verdict of accidental death was returned, the coroner describing the death as due to inflammation of the lungs, caused by an accident. The jury declared that no blame attached to Mr Hearne, the boy's housemaster, or to any official of the school.

Though the school was now in the clear, the three boys involved were still in serious trouble. Having been in custody for five days, they appeared before the Rcigate magistrates on Tuesday, January 25 (the day of John Wainman's burial at Sneinton), charged with feloniously assaulting and killing the boy. William Hearne was again called, but had little to add to his previous account. He remarked that he had not asked John why he had been hurt, but thought that the lad would tell him. 'We often', said Mr Hearne, 'see rough play going on amongst the boys'. He also felt that John's sudden drop to the ground from the circle pole would not have happened if he had not called out from the schoolroom door. John Jeffries' story was not quite the same as in his statement of the previous day: he now declared that John Wainman had called down to the other boys to let him down, and that John 'cried out a little' when hit with the piece of rope. More serious for Charles Wyatt, Horace Golding, and William Smith, was John Wainman's deathbed deposition, made, it will be recalled, on Sunday, January 16. In this he described his ordeal, stating that he had been hit eight or nine times with a rope's end - James Carter had estimated the number of blows as only three or four - and giving his explanation of the incident. 'I was tied up and injured because my schoolfellows thought I knew about a boy named Harris who ran away the Saturday before this happened ... 1 think a boy named Jeffries stopped them beating me. I then went into the schoolroom and told Mr Hearne. He said, 'What is the matter?' and I told him they (the boys) had been giving me a doing about the circle pole. He then took me upstairs and said, 'You can go down to the doctors in the morning.' I went out into the field in the afternoon and told Michael Miles, the younger, I could not work because the boys had been giving me a doing. I was in bed on Tuesday, and on Wednesday I walked to the doctor, Mr Berridge, at Redhill, and he put bandages on my arm. When I got back I went to the schoolroom, and Mr Hearne forgot to send me up to the sick room. Mr Berridge, later in the day, sent a note down, and Mr Hearne then sent me up in the sick room, and I have been here since. I told Mr Hearne I was badly hurt on Tuesday. I did not feel it much before then. The boys in the house bore me ill-will about a handkerchief which was stolen by Masters, and brought trouble in the house. The master has been kind to me, and did not take part or encourage the boys to give me a doing. Mr Hearne has never flogged me, to call a flogging since I have been here, or ill-used me or knocked me about. Mr Hearne has punished other boys (Goodmanson and Floyd) for ill-treating me.' John Wainman made his mark at the end of this deposition, which was witnessed by Mr Pym, the major; Charles Walters, resident chaplain at the school: and Mrs Charlotte Wainman. Like her late husband, Mrs Wainman was unable to sign her name, making her mark with a cross.

John’s dying statement shows significant differences from that of Mr Hearne, particularly in the timing of events. The coroner, very anxious to know whether the lad had understood the meaning of the questions put to him, had (as reported in the paper) been told by the chaplain that John had remained quite conscious, although wandering a little in his mind. The coroner had then suggested. Probably the doubt as to the dates might have arisen from want of education?', to which Mr Walters had replied. 'From a want of power of thought.' It is also apparent that John Wainman had had his fair share of disagreements with boys in Gurney's house, quite apart from the three involved in his fatal accident. One should, perhaps, accept that in this last statement he was telling the truth as far as he could recognize and remember it.

When told, on January 20, that they would be charged with violently assaulting John, Wyatt, Golding and Smith had all said they were 'very sorry they had done it, but did not mean to hurt him. having done it in a lark'. They had gone on to say that the incident had occurred because John Wainman was 'always making a row and troubling the school.' Now. on January 25, the Rev. Charles Walters was in court to tell the magistrates something of the character of the three accused youths: through his comments he comes down to us as a sensible, if hard-pressed, man. They were, he said, 'very good specimens of the class with whom they had to deal', and in mitigation of the consequences of their action, pointed out that the boys had already been in police custody for eight days. He considered Wyatt 'an exemplary boy; in the school he was the master's right hand, and he had never given any trouble since he came, but always worked to keep down disorder and with much success'. Golding, who had run away eighteen months earlier, had been brought back to the school in September: 'He was well-behaved and seconded the work of Wyatt for the good of the house'. Smith, said Mr Walters, had never given any trouble in the school, 'but outside he had'. Asserting that they were 'three of the best specimens of boy' in the house, the chaplain stated that, but for them, the house would be in a state of disorder, as it had been a couple of years before. 'This', repeated Walters, 'was the sort of material they had to deal with'. The boys, he continued, acquired violent habits, taking the form of severe horse-play in which they indulged 'on the same principle - or want of principle - as the boys in a public school'. What the chaplain might well, one feels, have added in further defence of his boys, was that many of them were from backgrounds where violent behaviour was commonplace, and that any subsequent brutality was understandable, if not inevitable. Some serious incidents had occurred at the school, though without the fatal outcome of John Wainman's mishap. Mr Walters told of an injury done to two boys with a roller; a knifing that narrowly escaped causing death, and a case of 'lynch-law'. The school authorities did all they could to repress such cases, but there had, during the past year, been 29 instances of bullying in the five houses of the school, four of which had necessitated the locking-up of the offenders in the cells. Of the three involved in John's accident, he thought they 'would have been the last to injure the deceased.' The doctor was then recalled, confirming his final opinion that John Wainman's injuries were likely to have been caused by the boy falling against the steps projecting from the circle pole, as witnessed by William Hearne and John Jeffries.

Asked if they had anything to say, all three youths stated that John's injury 'was not done intentionally'. The mayor, as chairman of the bench, summed up very fairly. He said that the chaplain's remarks would, very properly, go in favour of the prisoners, but that it was not for the magistrates to weight evidence, merely to decide whether there was a case for committing the prisoners for trial. He agreed that John Wainman's death had not been brought about by design, but by horse-play. Notwithstanding the absence of any intention to cause death, or even to do any serious damage, death was the result of the violence that had taken place. The prisoners were thereupon formally committed to gaol, to await the next Surrey Assizes at Kingston. Though it was nowhere stated, the fact that all three boys were older than John must have made their act of bullying appear in a worse light: against John's sixteen years, Wyatt was 17, and Golding and Smith 19, when the incident took place. They were, incidentally, almost invariably referred to at the time as 'boys': nowadays they would be 'youths' or 'young men'.

All the criminal cases at the Surrey Assize being remitted to the Central Criminal Court at the Old Bailey, the three found themselves on trial under much more widely reported circumstances. So it was that The Times of February 4 1881 reported the proceedings. 'The prisoners', ran its account, 'were indicted for the manslaughter of the boy, but the grand jury ignored the bill, and returned one for the assault. The Common Serjeant4, after hearing a statement on behalf of the prisoners, sentenced them to three days' imprisonment, the result of which was that the boys were at once taken back to the institution.' Very similar coverage appeared in the Nottingham Daily Express on the following day, but the Mid-Surrey Mirror, with its special interest in the affair, printed a far more detailed report of the proceedings in its issue of February 5, with the headline:

'THE PHILANTHROPIC AFFAIR.

TRIAL OF THE PRISONERS'

This described how the boys, committed by the Reigate Magistrates, were indicted on the Monday on two accounts, the first charging them with killing and slaying John Wainman, the second with committing a common assault. Addressing the jury, the Recorder pointed out the three boys were charged with the manslaughter of a schoolmate, having by their violence caused a fracture of his shoulder blade. It appeared, continued the Recorder, that this was the outcome of 'rough play between the parties', and he therefore directed the jury not to find a true bill for manslaughter, but to return one for assault and causing actual bodily harm.

Two days later, Wyatt, Golding and Smith were brought up on this lesser charge before the Common Serjeant, Mr Charley. They pleaded guilty. Judgement was postponed until the arrival of the chaplain of the Philanthropic School, who reached the court at one o'clock. Mr Walters, who must have been experiencing a period of great distress, again asked permission to say something about the boys. First, though, he was requested by Mr Charley to outline the circumstances of John Wainman's death. This done, he repeated, almost word for word, what he had said at the inquest concerning the defendants. On the chaplain's stating that Smith had never given any trouble in the school, a warder deposed that William Smith had been tried at the Central Criminal Court on December 22 1880, for breaking into a church. Found guilty of common larceny, he had been sentenced to 7 days' imprisonment, and sent back to the reformatory.

In 1877 Smith had received six weeks in gaol, followed by four years in the reformatory, for stealing an umbrella. 'Of the other lads he knew nothing.' Recalled to the witness box, Mr Walters stated that Charles Wyatt, who had come to him from Southwark police court on a three year sentence, was 'a most exemplary boy, and, had opportunity offered, would have been sent out on license.' Golding, like Smith, was serving four years at the Philanthropic School, having been sentenced by the Hastings magistrates. Further questioning the chaplain, Mr Charley wanted to know whether the boys had trampled on John Wainman as he lay on the ground after dropping from the circle pole. Mr Walters replied: I think it is likely they did, but not intentionally, in scuttling away at the appearance of the master.'

In sentencing the three boys, the Common Serjeant showed the good sense we have already observed at the inquest and magisterial enquiry. He said 'he thought it was a cruel thing to string up the boy in the way described, but he did not think it was a case for severe punishment. The sentence of the Court was that they should be imprisoned for three days, which would allow them to be at once discharged.' As already related, Wyatt. Golding and Smith were returned immediately to the school at Redhill.

The Philanthropic Society sent details of the whole affair to the Inspector of Reformatory and Industrial Schools, and also kept the Nottingham Borough authorities informed about John Wainman's death and its aftermath. No trace, however, has been found of this later correspondence. John's burial at Sneinton on January 25 1881 went unnoticed by the Sneinton Parish Magazine, but, on the very day that his body was returned to Nottingham, a local periodical quite coincidentally included a leading article of eerie appropriateness. This was the shortlived Nottingham Society, which, under the headline JUVENILE OFFENDERS IN NOTTINGHAM', looked forward to a Parliamentary Blue Book promised by Sir William Harcourt, the Home Secretary, on the treatment of child criminals. An extract gives some idea of the tenor of the article: As a natural consequence of treatment of young delinquents, they have been hardened in crime, have been further removed from kindly influences, and in short banished into the society of evil-doers, in the vain hope that they may repent and then do well. We have inflicted such punishment upon youthful offenders as could have no effect but to harden their hearts and debase their morals; and then, after we have completed their ruin, we have increased the punishment . . . Not a day passes without the local magistrates being called upon to deal with some infant thief, and at the end of last week quite a batch of young evil-doers appeared before the Bench . . . Any scheme for dealing effectively with juvenile offenders must, in order to be just and impartial, deal with the manufacturers of our modern 'Artful Dodgers'. It is a notorious fact that many children are taught and trained to steal from their infancy. Their parents or guardians have commanded them to lead a lawless life; like other children, they have merely obeyed their parents . . . The poor child, therefore, has no chance. On cither hypothesis it suffers punishment. Neither parent nor magistrate will show it a better way . . .' Not all of this, of course, would have applied to John Wainman. Far from instructing him in criminal behaviour, his honest mother had taken him to the authorities. John was, however, clearly open to temptation, and unable to resist it. One cannot escape the conclusion that, in prison, and at the reformatory, he must have found himself in the company of criminals far more hardened and experienced than himself. As Mr Walters had said of John's three tormentors: 'This was the sort of material they had to deal with.' None of this is any criticism of the Philanthropic Farm Schools, whose staff, on the evidence of this case, appear to have been admirable. It is probable that John Wainman was healthier and better fed at Redhill than he ever was at Sneinton, but to arrive at the school as a thirteen year-old gaolbird was, by any yardstick, a pretty dreadful start in life. No doubt the authorities at the school looked forward just as eagerly as Nottingham Society to Sir William Harcourt's Blue Book.

A few weeks after these unhappy events, the 1881 census was held. It found Mrs Charlotte Wainman still at 1 Portland Place, Walker Street. She now gave her age as 50, having admitted to being 42 10 years earlier, on the occasion of the previous census. Although the Philanthropic School records had described her as a 'washerwoman', she here gave her occupation as 'laundress': perhaps this sounded a bit grander. Mrs Wainman continued to have a boarder, by now Mary Anne Cope, a 17 year old lace hand.

One final puzzle remains. A decent slate headstone was put up at Sneinton in John's memory, by Jackson of Mansfield Road, Nottingham. William Jackson's Christian Memorial Depot was a well-established firm in the town, but no records of the business survive to reveal the identify of the person who paid for the stone. Mrs Wainman was, surely, too poor to have found the money herself: perhaps John's numerous aunts and uncles came to her assistance? The boy's epitaph is neatly, though not especially artistically, carved, but a large blank expanse remains below the inscription, and it is surprising that the opportunity was not taken to commemorate John Wainman, senior, who had lain in the churchyard for over twelve years before being joined there by his son. And the verse? Whoever chose it (and we must assume that it was Mrs Wainman) was harsh and unforgiving. Had it been otherwise, the monumental mason would never have carved the grim lines that prompted the disclosure of this strange story.

'By cruel hands his sufferings come,

And from his friends was snatched away.

He now lies silent in the tomb,

There to wait the judgment day'

JOHN WAINMAN’S SNEINTON, with his home, no.1 Portland Place, marked by an arrow. The boy attended the National School at the extreme right of the map, and the present location of his gravestone is marked with an 'x'. (From an Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map).

JOHN WAINMAN’S SNEINTON, with his home, no.1 Portland Place, marked by an arrow. The boy attended the National School at the extreme right of the map, and the present location of his gravestone is marked with an 'x'. (From an Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map).MY GRATEFUL THANKS go to the following people: to Robert Simonson and Julian Pooley of Surrey Record Office, for copious information on the Philanthropic Society School, and on John Wainman's admission and death: to Selwyn Eagle, for digging out, in the British Library Newspaper Library, photocopies of the inquest and trial reports in the Mid-Surrey Mirror: to Don Coleman, Director of the Royal Philanthropic Society, for permission to quote from the school's admissions register: to Prit Chahal, for explaining John Wainman's injury to me: and last, but by no means least, to Brian Jackson, who drew my attention to the gravestone in the first place.

1. James Weston Townroe, of 7 Bilbie Street, Nottingham, had been in business as an agent in the town for many years before becoming ordained in 1878, when in his late sixties. He later became vicar of St Peter-at-Gowts, Lincoln.

2. Further research might determine whether this was the John Knight who had reported the death of John Wainman, senior, at Langley Mill, or whether we arc dealing with two men of the same name.

3. The Philanthropic Society's Farm school was, as already noted, modelled on the public school system. Anyone who believes that bullying did not exist in 19th century public schools need only read Tom Brown's Schooldays.

4. A senior barrister, and judicial officer of the City of London, who sat in the Central Criminal Court.

< Previous