< Previous

BRUSH AND PEN:

William Kiddier and his work

By Stephen Best

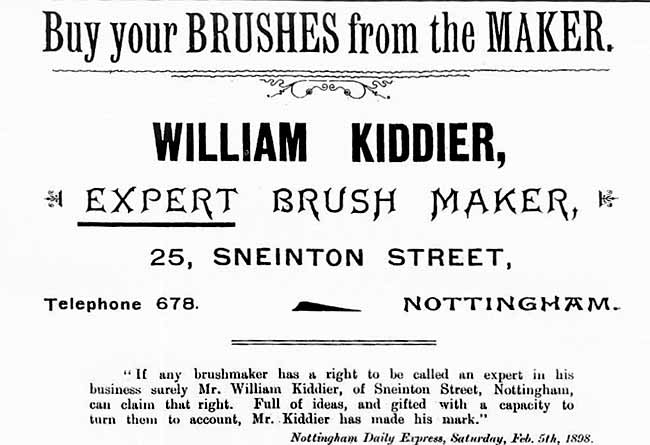

FEW RESIDENTS OF SNEINTON can ever have possessed a greater range of talents and energies than William Kiddier, who came to Nottingham in 1862 as a young child. Born in Loughborough on July 23 1859, he was named after his father, a brushmaker, who moved to this area three years later to expand his business. William Kiddier senior set up at 23-25 Sneinton Street, now Lower Parliament Street: his premises were almost exactly on the spot now occupied by Sun Valley amusement arcade.

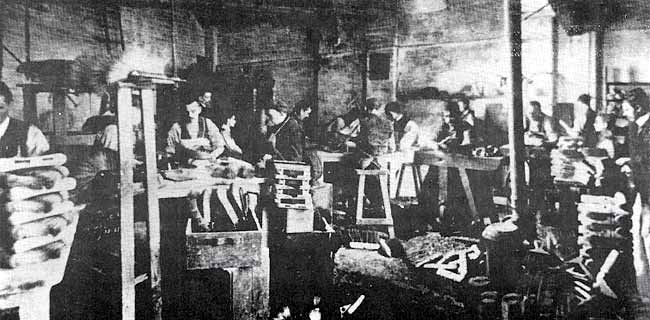

The infant William attended Holy Trinity Schools in the centre of Nottingham, while the Kiddier business evidently thrived as the family grew. By 1871, when the census recorded the Kiddiers as residents of Sneinton Street, William had been joined by five younger siblings, two boys and three girls: his 35 year old father was now the employer of two females, four men, and two boys. Before long the young William became one of his father’s workpeople, and was to recall, many years afterwards, that he had in 1879 visited Poland and Russia to look into aspects of the brush trade in Europe, and in particular 'to see how bristles were handled at the source'. Kiddier was later to bring to England a boar, which he presented to the Nottingham Council, who eventually placed it in the Natural History Museum. Clearly a man of great determination, William Kiddier would reveal, in his personal letters and published writings, his firm principles and strongly-held opinions.

In 1881 the family was listed in the census at 143 Alfred Street South: with a touch of fine distinction the father gave his own occupation as 'brush manufacturer' and that of his energetic son, recently returned from Russia, as 'brush maker'. Though the Kiddiers no longer lived at the shop, the Sneinton Street business premises were to be owned by the family until the nineteen twenties.

Thanks to William Kiddier’s passion for drawing and painting, we can keep track of his frequent changes of address over the next ten years or so. From the early 1880s work by him was shown at the annual Local Artists’ Exhibitions at Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery, whose printed catalogues included the home addresses of most exhibitors. From Alfred Street South in 1881, Kiddier had, by 1888, moved to Blue Bell Hill, and was in 1889 at Broad Oak Street, off Corporation Road. By 1891 he was living at 10 Promenade, off Bath Street, where he was to remain for much of the decade. An echo of his visit to Russia is perhaps heard in a lengthy set of verses presented to him at Christmas 1890 by the Nottingham poetaster George O’Byrne: these survive in manuscript at Nottinghamshire Archives Office, with the heading: 'To Mr Kiddier Junr, on receiving a Christmas present of Russian tongue'. Had William Kiddier kept up contacts made in Russia in 1879? The year 1895 saw the death of his father, the founder of the business: his last private address was Crown Street, off Carlton Road. Probate was granted to his widow Eliza, his daughter Annie, and to William, his effects amounting to £1,365.11.6d. The brushmaking concern was now in the hands of William Kiddier junior.

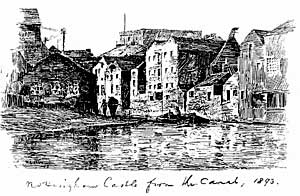

Nottingham Castle from the canal, 1893.

Nottingham Castle from the canal, 1893.An idea of the range of Kiddier’s artistic subjects may be gained from the titles of some of his exhibited pictures. In 1881 'Attenborough meadow': in 1889 'West Bridgford Church' (for sale at £4. 10s), and in 1894 a pen and ink sketch of High Bridge, Lincoln. In both 1892 and 1893 William Kiddier showed eight pictures at the Local Artists' Exhibitions, and in 1894 as many as thirteen, including views of Southwell, Wollaton, Ilkeston, Bridlington, and Great Yarmouth. A further seven appeared at the 1895 exhibition, following which he wrote from his Promenade house to Herbert Baker, secretary of Nottingham Society of Artists, of which Kiddier was a longstanding and prominent member. Thanking Baker for his help and interest, he added: 'My opinions are that too many works exhibited by one man are a mistake, so I have resolved, for the future, to be more select.'

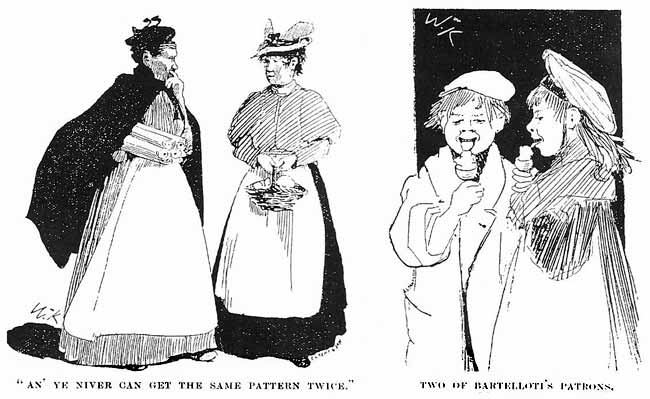

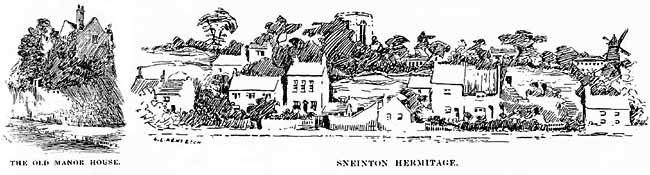

This same year marked the beginning of William Kiddier’s sole venture into public service, when he was elected a member of Nottingham School Board. Receiving 26,513 votes, he came fourth of the fifteen successful candidates. He served for three years on the Board, frequently voicing, according to contemporaries, independent views on the subject of education. In his last year he was chairman of the Board’s Finance Committee. Kiddier was also much involved with a little periodical called 'Echoes', originally subtitled 'The official magazine of the Nottingham Board Schools'. First published in 1897, it ran for several years, undergoing more than one minor change of title. Kiddier’s name appeared as editor of volume three. A miscellany of general interest articles and snippets of local history and topography, 'Echoes' included a number of pen and ink drawings by William Kiddier. Of greater interest to Sneinton readers was Kiddier's work for 'City Sketches'. This periodical lasted for barely a year, but during its short life contained many splendid drawings by Kiddier, in addition to several articles by him. In the issue of June 6 1898 there appeared 'The destruction of Sneinton Hermitage': the demolition of the White Swan public house and other old dwellings, to make way for the Great Northern Railway viaduct, had prompted him to tell the story of the celebrated Hermitage rock fall of 1829. William Kiddier accompanied this article with sketches of Sneinton Manor House, Dale Street, and the Hermitage. Later in the same month 'City Sketches' featured 'Something about Sneinton Market', followed a fortnight later by a second piece on the same topic. These are fascinating glimpses of the market as observed by Kiddier himself, and include wonderfully vivid pen and ink drawings of people he encountered there. William Kiddier also contributed to 'City Sketches' an article on the Nottingham humorous artist Tom Browne.

Kiddier was by now living in the prosperous part of Sneinton. The 1898 register of electors shows him at 3 Victoria Avenue, off Sneinton Dale. After a brief residence here he moved the few yards to the other side of Sneinton Dale, to a house variously described as 4 Dale Villas or 4 Victoria Villas. Now 41 Sneinton Dale, this was once the home of William Kiddier's friend William Hugh, headmaster of High Pavement School.

Artistic matters continued to take up much of Kiddier's spare time. In 1897 he had a leading part in the setting up of the Nottingham Atelier, founded with the object of providing local artists with the opportunity of studying, and painting from, the nude. He took the chair at the first meeting of this 'Proposed artists' life class', held at the People’s Hall, Heathcoat Street, on October 15 of that year. 'City Sketches' reported, in November 1898, the first annual meeting of the Atelier, speaking warmly of William Kiddier, its president, 'Who has now for many years, zealously devoted the leisure of an active life spent in business, educational and social work, to art, and is ready alike with pencil and brush ' One unhappy man at that first dinner, however, was John Beer, a Swedish artist working in Nottingham, who clearly felt that his own role in the forming of the Atelier had been accorded insufficient prominence. The Nottingham press reported that Beer rose to his feet to condemn the proceedings, complaining that there were men present, in white tie and evening dress, who had no soul for art. These men were gathered at the top of the table round the president, while the founders of the society had to take a back seat in a draught near the door. The room, he said, ought to have been filled with artists and friends of art. 'So it is', interjected another diner.

On February 16 1899, William Kiddier resigned from Nottingham Society of Artists. In a characteristically trenchant letter he wrote: 'The step is taken in order to get freedom of action in the best interests of art. My powers, I admit, are limited to a small sphere: but they are devoted to a great cause - a cause which is well expressed in the words, 'Greatest good to the greatest numbers'.' He offered his best wishes for the prosperity of the Society, 'ever keeping before it the high ideal that Art is not to be fettered nor confined to localities, nor pent up in institutions: but that it belongs to the people.' For some time thereafter, Kiddier's artistic allegiance was to the Nottingham Atelier: within a few years, its aims achieved, the Atelier was to be amalgamated with the Nottingham Society of Artists.

TWO OF WILLIAM KIDDIER'S DRAWINGS accompanying his Sneinton Market articles in 'City Sketches'.

TWO OF WILLIAM KIDDIER'S DRAWINGS accompanying his Sneinton Market articles in 'City Sketches'.1902 saw an etching of Kiddier’s reproduced in a special number of 'The Studio', and, at about this time he opened his famous brush shop in South Parade, next door to Smith's Bank. With his business premises on the ground floor, and a studio at the top of the building, much of William Kiddier's life was concentrated upon South Parade. In 1904 his work reached a wider public when one or two of his drawings were among the illustrations in a little book, 'As the years have passed by in Nottingham', by William Leaning, head teacher of Albert Street Schools, Bulwell. Kiddier was by this time not only once more a member of Nottingham Society of Artists, but a vice president of the Society. He was also exhibiting again at the Local Artists' Exhibitions at the Castle. Around this date, he moved house, leaving Sneinton for Thorncliffe Road, Mapperley Park. Although no longer a resident of Sneinton, he retained a connection with the neighbourhood through his brush manufactory in Sneinton Street.

In 1907, William Kiddier's first slim volume of poems, 'Sonnets', was published for private circulation by Cooke and Vowles of Nottingham -the subjects of his verses included three Nottinghamshire poets: Byron, Philip James Bailey, and Henry Kirke White. The following year, Kiddier had a painting accepted by the Royal Academy, though it was not, in the event, hung. This was 'For autumn', described as a 'striking landscape'. His work had already been seen at exhibitions of the Royal Society of British Artists and the Royal Hibernian Academy. About 1910 he changed his address yet again, moving this time the short distance to Zulla Road, still in Mapperley Park.

Further books of poetry appeared: in 1910 'Sonnets to a thrush', and in 1911 'Sonnets and a song'. The latter included verses with titles like 'Rain' and 'Morning mist'. It was during this period, not long before the Great War, that Kiddier first met a young man, eighteen years old, just making his way in the literary world. This was the Nottingham-born writer Cecil Roberts, who, in his autobiographical volume 'The years of plenty', remembered Kiddier as a staunch friend, kind and richly talented. Roberts also vividly recalled William Kiddier’s appearance: 'Striking head and face, the ringed eyes of an eagle, the white mane of a prophet'. According to Cecil Roberts, Kiddier frequently used to go upstairs to the studio above his South Parade shop, leaving his son Ernest to look after the business. Roberts described William Kiddier’s method of painting: although a landscape artist, he would paint indoors from sketches made in the open air.

The passage of time had not diminished Kiddier's sententious manner of letter-writing, as a note written by him on New Year's Day 1913 shows. Writing to a Mr Parr at Nottingham Society of Artists, he thanked him for sending notification of a forthcoming meeting of the Society, but continued thus: 'Pardon me, you are quite wrong in anticipating that I desire to take part in the future conduct of the society in the way you suggest. I made this quite clear at the dinner, where I stated that I had no time to engage in long and tedious discussions at meetings of the N.S.A.' Typically, one feels, these sentiments did not prevent his offering a number of suggestions for the better running of the Society's affairs. 'Get a strong council elected and do not ignore it as you appear to have done in calling this meeting', and: 'Let some of the younger men have an interest in the management and conduct of the society.' Later in 1913, William Kiddier's final collection of verse was published in Nottingham. Inscribed to J. Potter Briscoe, the City Librarian, 'Sonnets to a singer' included poems titled 'To a young poet', and 'To a dead poet'.

In 1915 a bust of Kiddier, by Joseph Else, principal of Nottingham School of Art, was exhibited at the Royal Academy, achieving 'a striking success'. The following year saw the publication of 'The profanity of paint', the first of three volumes later described as 'eulogies on the role of colour in painting'. It contained a number of short prose pieces, sometimes of only one or two paragraphs, on such topics as 'The magic of words' and 'The masterpiece'. A couple of the pieces gave clues about Kiddier's view of the social order. In 'The people's cafe', he wrote: 'I do not care to see many rich people at one time. It was ordained that the percentage of rich should always be small A group of artisans never gives me an unpleasant thought: it is the natural order of things; the poor were regarded by Our Lord as the multitude ' Then, in 'The middle class'’, he observed: 'That I belong to the middle class is my chief misfortune; it is good to be born an aristocrat, but better an artisan'. Two further volumes of a similar nature came out in 1918 and 1919: 'The oracle of colour', and 'The painter's voice'. The latter was dedicated 'To my son, killed in action'. Ernest Kiddier had died in France on September 17 1918, and was buried in Queant Communal Cemetery. Kiddier felt the loss of Ernest very deeply: in addition to his natural grief, he now had to face his remaining years in business, knowing that there was no son to take any of the load from his shoulders.

In May 1919, an exhibition of William Kiddier's paintings was staged by the Fine Art Society of London at its Bond Street gallery. The sequel to this exhibition was a startling one, as the artist recalled in the 'Nottingham Journal' of March 5 1933. 'The sight of my pictures, many of which found purchasers, depressed me very much. I took back all that were left. One by one I put on the easel every unsold picture in my possession and one by one I condemned them. I cut each one off its stretchers with a sharp knife and stuffed it into the slow-combustion stove that warms my studio. I burnt 201 pictures in three days and never felt happier in my life My only regret is that I did not start burning before I had my show. Some of my pictures had been in the Royal Academy. I said 'Damn the Royal Academy' and burnt the pictures just the same!' Some accounts of the artist's career place the picture-burning episode after a one-man show of Kiddier's work at Nottingham Castle in August 1922. The artist thereafter placed much more emphasis on colour in his pictures, which were now filled with bright, and sometimes exaggeratedly vivid, tones. He changed his style, too, concentrating on oil painting in a vigorous manner-, described variously as 'in the impressionistic style', and 'almost Gauguinesque'. It is, however, a pity that, as the result of Kiddier's act of self-criticism, we know so little of his earlier style of oil painting.

A KIDDIER ADVERTISEMENT in 'City Sketches'.

A KIDDIER ADVERTISEMENT in 'City Sketches'. A final phase of his literary career opened in 1922, William Kiddier contributing to Pitman's 'Common commodities and industries' series a little volume titled 'The brushmaker'. Written from his deeply-felt socialist viewpoint, it gave an account of the secrets and mystique of the old craft of brushmaking, mentioning in passing the author's visit to Poland and Russia over forty years earlier. Some of Kiddier's line drawings illustrated the text, which was afterwards described as the standard modern work on the subject. In 1923, however, he ceased to be a practising brush manufacturer, disposing of his shop to the Royal Midland Institution for the Blind, who ran it as part of their brush making and selling business. To the public at large the shop continued to be known as Kiddier’s and, until after the second world war, the prominent sign ’KIDDIER MAKES BRUSHES’ could be seen above South Parade.

In 1930, William Kiddier’s last book was published by Allen and Unwin: ’The old trade unions, from unprinted records of the brushmakers’. The author’s foreword (or, as he called it, word beforehand) gave an early taste of his passionate feeling for his subject: ’Men with a trade in their fingers - the Old Brushmakers: I knew them well. Their trade was my trade. My first book on this matter was written in the shade of the workshop: in the pleasant smell of the pitchpan. Now I write obsessed with the spirit of the Old Clubhouses. The Brushmakers’ Clubhouses were real needful things: hallowed spots, where men out of work got a little money, and men in work paid a little .... My blessed guide is the plain handwriting of good men. Men chosen by their workmates as good spellers and honest ..... I have the precious Minute Books before me as I write ...'

The tone of the book was, one feels, remarkable, given that its author was a septuagenarian who had been a successful businessman and employer. One chapter was headed 'Politics of men without votes', and William Kiddier's strong opinions were voiced throughout. Two examples must suffice here. Describing the background to a strike at Manchester in 1866, he wrote: 'The real gravity of the strike is known only to those who suffer starvation by it: others may talk. Hunger in the people is articulate. The strike may suit the purpose of employers having a glut of goods: but what of men out of work, with no glut of food?’ Later in the book he argued: 'To the Brushmakers EQUALITY and WAGES were inseparable. Politicians may twist EQUALITY into EQUAL OPPORTUNITY: and the working man and his society be damned.' The capital letters are Kiddier’s, not mine.

By now William Kiddier had moved house for the last time, his changes of address having marked a life of steadily increasing prosperity and standing: Sneinton Street, Alfred Street, Blue Bell Hill, Broad Oak Street, Promenade, Victoria Avenue, Victoria Villas, Thorncliffe Road, Zulla Road, and now, finally, 3 Marlborough Road, Woodthorpe. He remained throughout true to his political convictions, and to his Nottingham accent - one is tempted to believe that Kiddier might have taken very good care not to lose his provincial accent.

On July 4 1931, he wrote from Marlborough Road to Walter Briscoe, the City Librarian. New extensions to the Central Library in South Sherwood Street were being planned at the time, and Briscoe had evidently sounded out Kiddier on the subject of acquiring some of his work for the library. Kiddier's reply was typical of him: he stated his mind very firmly (with, it must be admitted, that touch of fussiness, self-importance even, which characterized much of his correspondence), before concluding with a graceful compliment to the recipient of his letter. 'Some time ago we talked about my pen and ink sketches, among which arc a number of local bits.

I would like you , sometime, to make a selection for the Public Library. You will have ample wall space when the new building is complete. For the time being, please make a note of this fact, that I give a number, say twenty, of these drawings, through you as a dear friend, to the City of Nottingham. I want you yourself to select what you think will be of public interest. The number may, on these grounds, be extended. But here again, I want you to limit the collection to the measure of real service. Perhaps the matter of selection could stand over until you are settled down in your new quarters. Meanwhile, I think of your worth, give you my blessing, and remain, Yours faithfully .....’

Later that year, on October 18, William Kiddier wrote another trenchant letter, this time to Lewis Richmond, a senior journalist (and future editor) of the 'Nottingham Journal': 'Dear Richmond, you have an old portrait of me in your 'cemetery'. Your paper has used the block on two or three occasions. Now, please burn it. If you want another block, at any time, you will find the enclosed print will reproduce well without any touching up'. Once again there was a charming tailpiece: 'That cup of coffee last night was made very sweet by your personal magic.'

BRUSH MAKING at Kiddier's, from 'Nottingham past and present', 1902.

BRUSH MAKING at Kiddier's, from 'Nottingham past and present', 1902.Towards the end of 1931, a new edition of Kiddier's 'The old trade unions' was issued, and on November 23 the author sent a presentation copy to his friend, the local poet Sam Fisher. Accompanying it was yet another idiosyncratic letter: 'The New Edition, I trust, will, in a measure cancel the first edition, which, as I told you, was touched up after the final proofs left my hands. The touching up, of course, was fractional, like a spot or two on a big canvas. But, damn it all, if the book had been a canvas - my canvas -and I had caught the rascal at it I would have knocked him down.'

In old age, William Kiddier was finding that his paintings were receiving wider recognition. Exhibitions of his work had been staged in Nottingham and Glasgow, and now, despite the death, on July 6 1932, of his wife Ellen, he felt able to take part in the planning of a one-man exhibition at the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, the following spring. The 'Nottingham Journal' remarked that 'the distinguished colourist is much admired in Hull'. All the pictures shown were from the output of the previous dozen years, because, as we already know, and as Kiddier himself succinctly observed, 'I have nothing earlier.' A week or two later Lewis Richmond of the 'Journal' asked Kiddier for an account of the Hull exhibition, to appear in his paper. At that time, however, an exhibition of the local artist Denholm Davis was being staged in Nottingham, and Kiddier, in what must be our last glimpse of him as a letter writer, replied to Richmond on March 19 1933: '....the note you ask for about my own one-man show at Hull must wait. Just now it is Davis's turn. He alone must top the bill. My own show must not be on the bill at all.' The Hull exhibition gave rise to a curious story. It was said that William Kiddier, while riding in a train on his way home from Hull, had been deeply impressed by the sight of an old church, lit by strong sunlight. As soon as he arrived in Nottingham, he set to work on a full-sized painting of the building, which was framed and sent to Hull, the painting going on display there barely 24 hours after he had left the exhibition. Can this, one wonders, be true? It does seem to bear all the marks of a tall story.

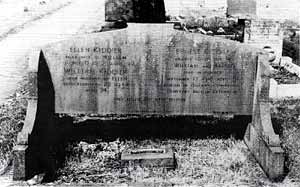

In the winter of 1933-34, a further exhibition of Kiddier's work was put on, this time at Leicester. By now, though, the painter's health was failing. Unwell for several months, he was confined to bed for some time before dying at home in Marlborough Road, on February 22 1934. He was 74, and was survived by his daughter Alice, herself an artist, who had first exhibited at the Local Artists’ Exhibition in 1914. The Nottingham press was generous in praise of him, and William Kiddier’s patriarchal face gazed out from the pages of the local newspapers. The 'Nottingham Journal' headline ran: 'ARTIST AND POET. MR WILLIAM KIDDIER'S DEATH. NOTTINGHAM LOSES UNIQUE FIGURE', while the 'Evening Post' story was headed: 'NOTTINGHAM ARTIST PASSES. BUSINESS MAN WHO BECAME NOTED FOR PAINTINGS. AUTHORITATIVE WRITER’. The funeral took place on February 26, at Redhill cemetery: among the mourners were representatives from Nottingham School of Art, Hull Art Gallery, and Arnold Urban District Council. Friends from Nottingham Society of Artists included the painters Denholm Davis (whose work Kiddier had been so anxious not to upstage) and Arthur Spooner. Cecil Roberts was present, as were several people from the Royal Midland Institution for the Blind. Wreaths were sent by the Robin Hood Lodge of Freemasons, Nottingham Society of Artists, Arnold Labour Party, and Arnold Labour Party club.

TWO MORE KIDDIER SKETCHES from ’City Sketches': Sneinton Manor House and Sneinton Hermitage.

TWO MORE KIDDIER SKETCHES from ’City Sketches': Sneinton Manor House and Sneinton Hermitage. DALE STREET AND SNEINTON CHURCH, a pen and ink sketch by Kiddier which appeared in 'City Sketches', 1898.

DALE STREET AND SNEINTON CHURCH, a pen and ink sketch by Kiddier which appeared in 'City Sketches', 1898.Some of William Kiddier's drawings of local subjects did, as he had promised, find their way into the local collection at Nottingham Central Library. Shortly after the artist's death, Sam Fisher wrote to the City Librarian: 'I have received your letter concerning Mr Kiddier’s drawings. I happened to see Miss Kiddier this morning and mentioned it to her, and she is bearing it in mind.' Fisher added a postscript: 'I feel the loss of our dear friend very much.' About a dozen drawings came to the library, rather fewer than Kiddier had indicated in 1931: they are now in the Local Studies Library at Angel Row. Included among them are a portrait of the painter Harold Knight, and the views of Sneinton and the canal reproduced here. There are also pen and ink drawings of places such as Bridlesmith Gate, Wilford Church, the Old Town Hall, the Postern Gate pub, and Friar Lane Chapel. The library also possesses Kiddier's oil painting of the Trent at Colwick.

Not long after Alice Kiddier's death, an exhibition of William Kiddier's paintings and drawings was held at Victoria Street Gallery in September and October 1969. Most of these were works from the 1920s bequeathed by Miss Kiddier to the Nottingham and Leicester art galleries, for sale. The exhibition also included portraits of Kiddier by three other Nottinghamshire artists; Harold Knight, Sir William Nicholson, and (in bronze) Mary Gillick. Interviewed at the time, Eric Laws, curator of the Castle Museum and Art Gallery, described William Kiddier as 'a scornful, arrogant man,' and added: 'I find myself admiring him very much. Considering he lived in the middle of the provinces he was remarkably original for his period. His work stands the test of time.' Perhaps it should be mentioned here that the Nottingham Castle collection includes five oils by Kiddier - 'The dyke', 'Snowbound windmill', 'The scarecrow', 'St Crispin', and 'West wind'. None of these was on display when I recently visited the Castle: the last two named, however, are quite new additions, so it is good to know that Kiddier's work is still being acquired by the city.

WILLIAM KIDDIER'S GRAVESTONE at Redhill cemetery, Arnold. (Photo: Stephen Best).

WILLIAM KIDDIER'S GRAVESTONE at Redhill cemetery, Arnold. (Photo: Stephen Best).To end on a personal note, I must add that, like Mr Laws, I have come to view William Kiddier with much respect. For my taste, his poems and essays are marred by a too-precious literary style, and seem very dated now. Tastes, however, change, and all of this no doubt went down very well with readers in the first two decades of the century. His books on brushmaking are, I think, very interesting: we are again treated to some purplish prose, but the underlying subject knowledge and passion of the man come across clearly. I am no art critic, but Kiddier's pen and ink drawings appear to me to be highly accomplished, besides being valuable contributions to our local history. As a man Kiddier was, as we have heard, inspiring and generous; as a correspondent, he knew how to mix pomposity with charm, quite a heady brew on occasion. Sneinton has reason to be proud of this neglected former resident. Perhaps one, at least, of his homes in the neighbourhood deserves to bear a commemorative plaque?

All quoted extracts from William Kiddier's letters are from items at Nottinghamshire Archives Office: these include a substantial deposit from Nottingham Society of Artists. Published sources consulted by me are acknowledged as they occur throughout this article, but I wish also to express my indebtedness to Heather Williams, whose unpublished thesis, 'The lives and works of Nottingham artists from 1750 to 1914 ..... ', has been of great help in drawing my attention to useful sources of information on Kiddier. Illustrations are reproduced by courtesy of Nottinghamshire County Local Studies Library, except where otherwise indicated.

< Previous