< Previous

THE SEARCH FOR THOMAS MARTIN:

another tale from St Stephen's churchyard

By Stephen Best

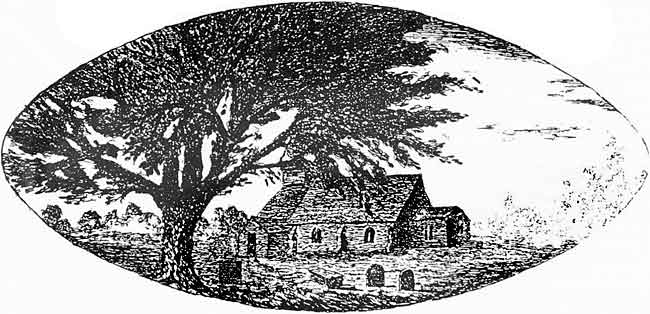

THE ABOVE ENGRAVING, published in Throsby’s revision of Thoroton’s 'Antiquities of Nottinghamshire' shows Sneinton church and churchyard in the 1790s.

THE ABOVE ENGRAVING, published in Throsby’s revision of Thoroton’s 'Antiquities of Nottinghamshire' shows Sneinton church and churchyard in the 1790s.THIS IS A JIGSAW PUZZLE OF A STORY: a jigsaw with more than a few pieces missing. It does, however, show how an apparently insoluble mystery may, quite unexpectedly, find some light shed on it. Like several other local puzzles disentangled in earlier issues of the magazine, this one concerns a memorial in Sneinton churchyard.

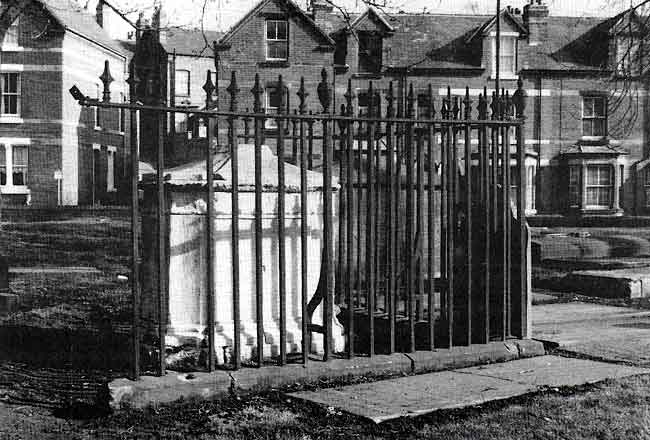

Among the monuments there are two or three which must once have been imposing, but have become sadly dilapidated over the years, and are now bereft of any inscription. One such stands a few yards from the east wall of the vestry of St Stephen’s church: in addition to any means of identification, it has lost one and a half sides of the wrought-iron railed enclosure, embellished with elegant little urns, which formerly surrounded it on all sides. The tall stone tomb has marks, showing where the inscription tablets were once attached to its ends and sides, while its top slopes up from the edges to where there was once a crowning central feature. The monument evidently commemorates someone of substance, but there seemed little prospect of ever discovering the identity of the person buried here.

Now for the first chink of light. Writing in Sneinton Magazine no. 36 about George Green, I mentioned in passing that a particular reference to him was supposed to exist in Percy J Cropper’s manuscript notes on the history of Sneinton, but that their whereabouts were unknown. A friend, who had not read this comment, but knew of my interest in Sneinton matters, later told me, out of the blue, that the Cropper notes were to be found in the Department of Manuscripts at Nottingham University. Several visits to the University, and an examination of these papers, revealed copious historical information, a good deal of it available from other sources. A completely unexpected discovery awaited, however: among Cropper’s notes on Sneinton church were details of a number of monumental inscriptions seen by him in the churchyard, sometime around the year 1890. Of these, one entry in particular began to disperse the fog.

Cropper stated that a few yards east of the vestry, next to a flat stone in memory of William Frudd, was a stone memorial, surrounded by a fence of iron rails, 5 feet 6 inches high, on a low stone sub-wall. The tomb was surmounted by a stone urn, and bore on its north side a shield and arms - three dogs or lions, he thought. There had been a crest, but this had been broken off. Stone slabs on the ends and sides referred to several people, one inscription being especially striking:

READER

If thy Integrity invites unhesitating Trust:

If thou fulfillest with Honour and Affection

the Duties of a Husband:

With solicitous Kindness those of a Parent:

With self forgetting Zeal those of a Friend:

With the most liberal Bounty those of Hospitality:

and

With the most melting Compassion those of Charity:

Then tho the mortal part of

Thomas Martin

Rests beneath this marble:

Yet his Spirit lives in thy Bosom

d. Nottingham July 7 1796, aged 46 years

This was, without doubt, the memorial which had puzzled me for so long. The monumental inscription recorded by Cropper suggested a man of exemplary qualities; indeed, one cannot imagine that a finer epitaph was ever written over a grave at Sneinton. Who, then, was this paragon, whose name was quite unknown to me? A search of relevant issues of the Nottingham Journal revealed the bare details. On July 11 1795 there appeared this brief announcement: 'Died on Tuesday last, after a few hours illness, Mr Martin, hosier, of this town'. A week later, the same newspaper reported: ‘On Wednesday last the remains of the late Mr Martin, of this town, were carried for interment to Sneinton, attended by a very respectable retinue of his friends and acquaintance.' For comment on events in late 18th century Nottingham, it is always worth glancing at the diary of Abigail Gawthern of Low Pavement, that partisan Tory gossip and observer of life in the town. Sure enough, she noted Martin’s death, providing a further interesting detail: 'Mr Thomas Martin was taken ill at the Flying Horse in this town, Monday Jul. 6, and died the 7th; he was buried at Sneinton on the 15th.'

A well-known businessman, then, cut off abruptly in his prime; but the newspapers of July 1795 seem to have had nothing further to say about him. Phillimore's 'County Pedigrees: Nottinghamshire' however, proved a mine of information on the Martin family. Cropper had, by the way, been correct in thinking that the arms on the Sneinton tomb might have been three dogs - the Martins had, without official sanction, used armorial bearings of three talbots; the large hounds, now extinct, which appear as supporters to the arms of the Earls of Shrewsbury. Thomas Martin was baptized at Gotham on April 2, 1749, the son of the Rev. Samuel Martin, rector of that Nottinghamshire village. The rector had been educated at Oxford, where he became a fellow of Oriel College. Later he was a master at Appleby Magna School, Leicestershire, and rector of Newton Regis, Warwickshire, before moving to Gotham. In 1766 he published 'A Dissertation of the nature and effects and consequences of the blasphemy against the Holy Ghost'. Possessing property at Radford, Lenton and Basford, the rector was one of seven Samuel Martins in the family in as many generations, five of these being clergymen.

Another of the numerous Samuels was Thomas Martin’s elder brother. He became rector of St Peter’s, Nottingham, in 1767, when in his middle twenties, and was 'a gentieman of great learning, and remarkable for his skill as a critic in the Greek and Hebrew Languages'. Samuel Martin died, aged only 39, on September 12, 1782, at Stoke Bardolph. His death, too, was recorded by Abigail Gawthern, whose diary contained this vivid entry: 'The Rev. Mr. Martin, the rector of St. Peter's, went with my father and Mr Plowman to Btolph [Stoke Bardolph) a-fishing; they spent the day there: in the evening they mounted their horses to return and Mr Martin fell from his horse in a fit, it was supposed, and was taken up dead.... ' He left property at Basford, Radford, Lenton and Wilford in the Nottingham area; at Woodhouse in Leicestershire; and at Birmingham. It was elsewhere suggested that Samuel Martin died as the result of being thrown from his horse, but in the light of what we shall learn of Thomas Martin’s death, Abigail Gawthern's hint of an apoplectic fit is an interesting one.

THOMAS MARTIN'S MONUMENT IN 1992, At the time of his burial in 1795, the churchyard overlooked open countryside.

THOMAS MARTIN'S MONUMENT IN 1992, At the time of his burial in 1795, the churchyard overlooked open countryside.Concerning Thomas Martin, Phillimore quoted, without attribution, that 'he was one of the most eminent of the merchants engaged in the hosiery manufacture of Nottingham’, further stating that ‘he died of apoplexy after making an eloquent speech at the County Hall, Nottingham.' The source of this assertion, and its likely accuracy, will be discussed in due course. Thomas Martin was the husband of Jane Mitchell (or Michell), a lady from near Taunton in Somerset; the couple had three children, of whom more later.

With the information so far discovered, it was possible to find out a little more about Thomas Martin’s business activities. In 1770, at the age of 21, he was made a Burgess of Nottingham, entitling him to vote in elections for the Town Council and Parliament, and to the right of being elected on to the Council. He was admitted to the rank of Burgess by gift of the Corporation; usually the sign of a man they wished to honour, or whose vote they needed. One suspects that, in Martin’s case, the second reason applied. A poll book of 1774 records the vote of 'Thomas Martin, hosier, High Pavement': on this occasion he voted for the Whig candidate, standing in opposition to a Tory. This action would not have earned Thomas Martin the approval of Abigail Gawthern. Eight years after this election, Martin moved from High Pavement, leasing, on October 26, 1782, a house on the south side of Castle Gate, adjoining St. Nicholas’s churchyard. In the lease the property was described as a 'messuage, burgage, or tenement, with outhouses, buildings, yard and appurtenances thereof.'Thomas Martin lived before the day of the regularly issued trades directory, but the company in which he was a partner was listed in two such publications. In 1784 the business appeared as Statham, Martin and Barnett, 'manufacturers of hose in general', and in 1791 as Statham, Martin and Garton, hosiers. Samuel Statham, the senior partner, was also a shareholder in the Revolution Mill at Retford, a worsted-spinning mill which opened in 1788. As early as 1771, it seems, Thomas Martin had With the information so far discovered, it was possible to find out a little more about Thomas Martin’s business activities. In 1770, at the age of 21, he was made a Burgess of Nottingham, entitling him to vote in elections for the Town Council and Parliament, and to the right of being elected on to the Council. He was admitted to the rank of Burgess by gift of the Corporation; usually the sign of a man they wished to honour, or whose vote they needed. One suspects that, in Martin’s case, the second reason applied. A poll book of 1774 records the vote of 'Thomas Martin, hosier, High Pavement': on this occasion he voted for the Whig candidate, standing in opposition to a Tory. This action would not have earned Thomas Martin the approval of Abigail Gawthern. Eight years after this election, Martin moved from High Pavement, leasing, on October 26, 1782, a house on the south side of Castle Gate, adjoining St. Nicholas’s churchyard. In the lease the property was described as a 'messuage, burgage, or tenement, with outhouses, buildings, yard and appurtenances thereof.'Thomas Martin lived before the day of company in which he was a partner was listed in two such publications. In 1784 the business appeared as Statham, Martin and Barnett, 'manufacturers of hose in general', and in 1791 as Statham, Martin and Garton, hosiers. Samuel Statham, the senior partner, was also a shareholder in the Revolution Mill at Retford, a worsted-spinning mill which opened in 1788. As early as 1771, it seems, Thomas Martin hadthe regularly issued trades directory, but the been in partnership with Statham: Statham and Martin were numbered among 'The principal Masters and Employers in the Hosiers Trade, at and about Nottingham', who on May 20 that year placed an advertisement in the Nottingham Journal. This drew attention to malpractices among their out-workers, who were alleged to have spoiled yarn given to them for making-up; to have failed to return unused material; and to have stolen and sold for themselves the stuff delivered to them. At this time, and for many years afterwards, the hosiery trade was still very much a domestically based industry. Framework knitters, working at stocking frames in their own homes, or, perhaps, in a small workshop, would receive the yarn from the merchant hosier, and return the finished articles to him. Increasingly the hosiers, well described by a recent authority as 'merchant entrepreneurs', would come to own the frames, renting them out to the individual stockingers. Thomas Martin’s standing with his bankers was evidently high: in 1792, Statham, Martin & Co. had an overdraft of £5,756 from Smith’s Bank, Nottingham.

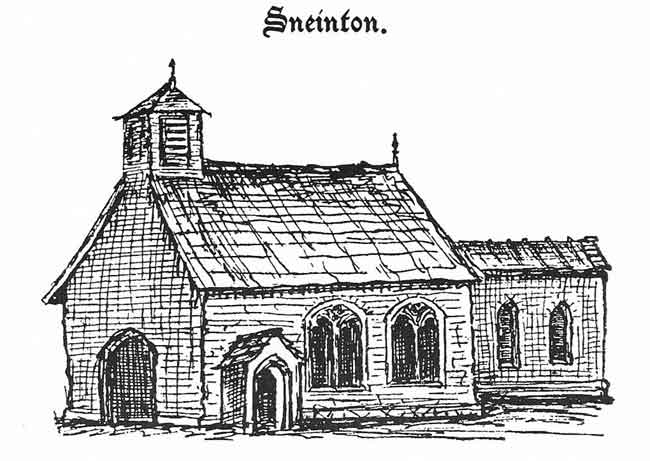

ANOTHER VIEW OF THE MEDIAEVAL CHURCH OF SNEINTON, demolished in 1810. This drawing appears in the printed volume of the Stretton manuscripts.

ANOTHER VIEW OF THE MEDIAEVAL CHURCH OF SNEINTON, demolished in 1810. This drawing appears in the printed volume of the Stretton manuscripts.'County Pedigrees' mentioned the publication in 1908 of a ‘History of the Martin family', written by Stapleton Martin of Norton, near Worcester. This rare volume could not be located in Nottinghamshire, but the British Library possesses a copy, and photocopies of its relevant pages helped to fill up more gaps in the story. Details of the inscriptions on the Martin tomb in Sneinton churchyard, recorded by Cropper, were confirmed by Stapleton Martin. One cannot assume from this that the memorial was still intact in 1908 - it is quite possible that family papers contained the information. Like Cropper, Martin gave the names of the other people commemorated on the monument: Jane, widow of Thomas Martin, who died at Bath in 1838, aged 79; Jane and Anna, their daughters; Thomas Seward Martin, their son; and George Dove, their nephew.

It is to Thomas Seward Martin that we turn next, for he was the first member of the family to be buried in the grave at Sneinton, the inscription reading: 'Here lieth the infant son of Thomas and Jane Martin, who died 1st May 1793'. Thomas Seward had been christened on the day before his death, at St. Mary’s church, Nottingham, in company with his twin sister Anna. The Sneinton parish register recorded the burial, on May 5, of ‘Thomas Martin fr. Nottingham'. The baby boy's middle name serves to introduce another member of the family, to whom we are indebted for some fascinating sidelights on the character of Thomas Martin and his wife.

This was his first cousin, Anna Seward, letter-writer and romantic poet, known as the 'Swan of Lichfield'. Born at Eyam in Derbyshire, where her father Thomas (husband of Thomas Martin’s mother’s sister) was rector, she spent 52 years of her life at Lichfield, where her father became canon and prebendary. A friend of Erasmus Darwin, she was praised by Dr. Johnson, and visited by Sir Walter Scott, who published her poems in 1810, with a memoir of her life. Her acquaintance with Johnson enabled her to give Boswell information for his biography of that most celebrated native of Lichfield. Although Anna Seward's work achieved considerable popularity, not all literary figures admired her style. In a wonderfully withering letter written in 1818, Mary Russell Mitford mused: 'I wonder by what accident Miss Seward came by her fame. Setting aside her pedantry and presumption, there is no poet male or female who ever clothed so few ideas in so many words. She is all tinkling and tinsel - a sort of Dr. Darwin in petticoats.'

Whatever her literary limitations, Anna Seward knew how to express herself movingly, as a letter, quoted by Stapleton Martin, shows. It was dated July 15, 1795, the day of Thomas Martin’s burial at Sneinton. In it Miss Seward told of the 'Loss of a dear friend, and the nearest relation I possessed - for he was my first cousin - Mr Martin (a son of Samuel Martin, of Gotham), one of the most eminent of the merchants engaged in the hosiery manufacture of Nottingham. Intimately known to me from our mutual infancy [Anna Seward was two years the elder], there breathed not a man for whom I felt greater esteem, or who more entirely merited the high reputation he bore... He was one that never thought his purse his own if his friend needed it. I have not found more truth and daylight in any human bosom with an understanding which would have done credit to any profession. I could tell you acts of beneficence of his that were more than generous - they were noble. Solicitously tender and ardent in his affections, there was a corresponding quickness in his resentments; but the violence was momentary - the least show of kindness could instantly appease him.'

Anna Seward went on to relate how Thomas Martin had suffered a fatal apoplectic attack immediately after making 'an eloquent speech in the County Hall, at Nottingham, in favour of the necessitous poor that hard winter’. She is thus seen to be the source of comments about Martin in 'County Pedigrees'. Her rather dramatic version of events, however, cannot be confirmed, and, as will be shown, it is possible that her cousin’s sudden death occurred some months after his efforts on behalf of poor people suffering the hardships of winter: July, in any case, seems an unlikely month in which to be making such an appeal. In her letter, Anna Seward described him as 'the best of husbands' further remarking: 'Though my beloved cousin was too generous, and lived with too much elegant hospitality to be very wealthy, yet I have reason to believe his wife, fifteen years younger than himself [she was actually ten years his junior], and her two little girls, will have a very genteel provision. Avoiding ostentatious expense she may render competence plenty.'

If Thomas Martin did indeed die just after his 'eloquent speech', the Nottingham Journal failed to mention the circumstances. We know from the paper that his last illness was of very brief duration, and from Abigail Gawthern that he was taken ill at the Flying Horse; certainly very close to the Exchange, if not to the Shire Hall or the Old Town Hall. The Journal of July 4, 1795, just three days before Martin’s death, did report the holding of a meeting in the Exchange Hall, for the purpose of helping the poor: Thomas Martin, however was not listed as present, nor did his name appear among the subscribers. A further meeting took place shortly afterwards; once again 'For the purpose of considering some mode of ALLEVIATING THE PRESENT DISTRESSES of the LOWER ORDERS of the COMMUNITY, in consequence of the VERY HIGH PRICE OF CORN and PROVISIONS OF EVERY KIND.' This sounds exactly the kind of event at which Martin, from what we know of him, might have spoken. Alas, it happened on the day following his death. Earlier in 1795, however, is harder evidence of the sort of public activity referred to by Anna Seward. The Nottingham Journal of January 24 reported a meeting, on the 19th of that month, at the Exchange Hall, for Raising a Subscription for the Relief of the Poor at this Inclement Season' - the winter of 1795 was an exceptionally bitter and severe one. In the list of subscribers to this most worthy cause was the name of Thomas Martin, who contributed the very substantial sum of five guineas. Some idea of the size of Martin's subscription may perhaps be gained by comparing it with the £30 given to this fund by the Corporation of Nottingham. It is, of course, possible that Thomas Martin was active in both of these local fund-raising causes of 1795, but one comes to the conclusion that, if he made a speech urging aid for the poor in the hard winter, then he made it in January, not in July.

To find out whether Jane Martin had, as suggested by Anna Seward, been left comfortably off at her husband’s death, it was necessary to examine his will. Like the lease mentioned earlier, this is housed at Nottinghamshire Archives Office. Dated February 16, 1788, it was drawn up when Thomas Martin was 39, and as yet childless. A very long document, it reveals him as a man of considerable means, with varied business interests. To his wife Jane he left ‘all his household goods and furniture, silverplate, towels, linen, china, all horses, widi bridles, saddles and furniture’. Small sums of money were left to his business partners in Nottingham, Samuel Statham and Henry Garton; and to his ‘worthy and much respected friends', Thomas Heathfield, merchant of the City of London, and John Stanford, merchant of Nottingham. These latter bequests were made 'as a small testimony of esteem and respect, and in trifling acknowledgement for their trouble in discharging Trusts reposed in them by the will': Heathfield and Stanford, together with Mrs Martin, were named as executors.

Among more substantial family bequests was £500, to be invested in trust for Thomas Martin's nephews Samuel and John Martin, but perhaps the most interesting provisions of the will concerned his wife Jane. First, he left her his rights in his partnership with Messrs. Wells, Heathfield and others in ‘the cotton mill at Sheffield’. This particular business interest of Martin’s was a quite unlooked - for find, and enquiries at Sheffield Libraries elicited valuable information on this firm. Thomas Heathfield, a London silk merchant (and executor of Martin’s) owned a mill in Devon, in addition to the one at Sheffield. His combined business partnerships represented one of the largest manufacturing textile concerns in the country. The managing partner of Heathfield, Wells & Co. in Sheffield was John Middleton, who had built a silk mill in the town. According to records in Sheffield, this was acquired in 1789 by Heathfield & Wells, burnt down in 1792, and rebuilt as a cotton mill. A correspondent, writing many years later to a Sheffield newspaper, stated that the mill managed by Middleton was worked largely by orphan girls from London; many of them deformed by ill-treatment, neglect or illness. Consequently: 'A strong prejudice existed against the proprietors of the mill, whether deserved or not the writer cannot say.' Middleton, the man on the spot, was held in particular opprobrium; so much so that, when the factory bell rang, local people (so went the tale) would say;

'Yonder goes dingleton, dongleton,

Devil fetch Middleton.'

Whether Thomas Martin was a partner in the mill at the time when these poor girls were employed there, we do not know. Even if he was, it should not be assumed that he was a callous employer. Notwithstanding the abuse heaped upon John Middleton, there is no evidence to suggest that their poor physical condition was the result of the girls' working for Heathfield, Wells & Co. All this is a mere digression, but there is a real puzzle about the Sheffield enterprise, as the reader may have noticed. The date given for the acquisition of the silk mill by Heathfield and Wells was 1789, and that of its burning down, before conversion to a cotton mill, 1792. How then, could Thomas Martin, in his will of 1788, have specifically left to his wife his rights in partnership with Heathfield, Wells and others, in the cotton mill at Sheffield? Unless Martin and his business partners had interests in more than one such mill in the town, one must assume that the purchase of the silk mill, and its subsequent destruction by fire, took place earlier than believed.

We come now to the second important clause in Thomas Martin's will. All his property at Newton Regis (the Warwickshire village where his father had been rector), or elsewhere in the United Kingdom; all his money securities, secured stock, and goods credits, were to be sold by Heathfield and Stanford for as much as they would fetch. The money thus raised was to be invested, and the interest paid to Martin's wife Jane, and then to any children the couple might have. Thomas Martin stipulated that none of this money be invested in public funds, 'Wherein from their fluctuating state and nature I desire no part of die said monies to be placed or vested.' The will was witnessed not in Nottingham, but by the master and two waiters of the London Coffee House; Martin no doubt travelled extensively on business.

On April 20, 1792, Thomas Martin added a first codicil to his will. A striking feature of this was the revocation of all bequests to John Stanford, and his replacement as executor by Martin's nephew Samuel. John Stanford was a great-nephew of William Elliot, a Nottingham silk throwster and, incidentally, the man who had leased the Castle Gate property to Thomas Martin. Around the middle of the 18th century, Elliot perfected the technique of dyeing stockings black, making a considerable fortune, and becoming one of Nottingham's wealthiest property owners. Having no children of his own, he set up his nephews as silk dyers, and retired to a country property at Radford. He created a lake in the grounds of his house, Radford Grove, by damming the River Leen, and erected a tower, or summer house, on an island in the lake. This eventually became the pleasure resort remembered as Radford Folly. Whether John Stanford (who later changed his name to Elliot) had quarrelled with Thomas Martin over business, one cannot tell, but it does appear significant that, besides replacing him as an executor, Martin revoked his personal bequest to Stanford.

A very important change had occurred in the Martin household since Thomas Martin had made his will in 1788; the arrival of the couple’s first daughter, Jane, Anna Seward wrote to Jane Martin senior on October 27, 1790, looking forward to the safe arrival of the baby. 'I congratulate you upon the effects of your tansy tea, and hope it will continue its Lucinian powers... Adieu, dear Mrs M, may you have a little longer health, succeeded by a comparatively little portion of pain, and crowned with a little living creature, who shall a great deal more than a little, compensate anything.' Lucina was the Roman goddess of childbirth - tansy tea was presumably thought to contribute to an easier confinement. Ten years younger than Thomas, Jane Martin became a mother in her early thirties. The child's birth caused Thomas Martin to change his instructions concerning the Sheffield cotton mill. This was to go in trust to Thomas Heathfield and Samuel Martin, who would carry on the business for the remainder of the co-partnership term. Income from this was to go to his wife for her lifetime, then to his daughter. Property purchased by him in Nottingham since 1788 was to be sold for the benefit of his widow - he had disposed of real estates in Warwickshire, Staffordshire, and Leicestershire. £2,000, with interest, was left to his wife, and £5,000 with interest, to his daughter. Various personal bequests were added, including £100 to Thomas Heathfield, and £100 or £50 to five relations. Thomas Martin's Sheffield partners Joseph Wells and John Middleton were each left £20.

Just about a year after the drawing up of this codicil, the twins Thomas Seward and Anna were born; the son, as we have heard, surviving only a day or two. Thomas Martin waited for a further two years before adding a second codicil to his will, written in his own hand. In this he revoked the £5,000 to his daughter Jane, instructing that it be divided equally between the girls, who would receive the money on reaching the age of 21. Martin was once again far from home when he wrote this codicil, which was witnessed by William and Mary Jackson, master and mistress of the inn at Bangor Ferry, and Robert Williams, bookkeeper at the inn, on May 6, 1795. Was it, perhaps, anxiety about the state of his health which made him decide to draw up the second codicil in a distant inn? As he did so, Thomas Martin had barely two months to live.

So we come back almost to where we started: to Martin's death. We can be reasonably certain that, in his final year of life, Thomas Martin was a busy man, actively engaged in business affairs and charitable causes. As to his character, we have the evidence of the now- vanished epitaph at Sneinton, and Anna Seward's letter. The monumental inscription was a glowing one, but then, it would hardly be otherwise. His cousin's letter, though, displayed an affection and admiration for him far above the conventional sentiments required by kinship and formal mourning. She acknowledged that Martin had a quick temper, but repeatedly stressed his generosity and kindness: independent evidence of this lies in his donation of £5 for the hard-pressed poor in the winter of 1794-95.

And his wealth? In round figures, Thomas Martin left something like £7,600, in addition to his share in the Sheffield cotton mill - a concern which, it will be recalled, was one of the biggest textile businesses of the day. His personal estate (not real estate) was declared to be less than £5,000. All of this confirms Anna Seward's judgment, that, although not fabulously wealthy, he was nonetheless, a rich man. A couple of comparisons may, perhaps, be instructive. At the time of Thomas Martin's death, a stockinger doing work for his company might have earned fourteen shillings (70p) a week - it was said that a comfortable livelihood was attainable by working six days a week, twelve hours a day. Also in 1795, the Corporation of Nottingham paid a constable £2.12.0 (£2.60) for 52 Saturdays’ attendance as a peace officer in the Market Place, and for 'keeping cattle off Beast Hill'.

Thomas Martin’s widow evidently had little difficulty in living in a style to which she was accustomed. After moving from Nottingham to Bath she bought a property at Winterbourne in Gloucestershire, where she was visited in 1804 by Anna Seward. The latter wrote of her that:‘She has several social neighbours of our rank of life' and noted that ‘the smart little widow', who moved in fashionable circles at Bath, had become 'a notable farmeress'. Mrs Martin lived until 1838, dying at Bath at the age of 79, and was buried at St Saviour’s church in that city. Her married daughter Jane died, aged 34, in 1825, at Hampstead and was interred at St. Sepulchre’s church, Newgate Street, in the City of London. She had been the second wife of a prominent legal figure, John Adams: serjeant-at-law, justice of the peace, and chairman of the Middlesex magistrates. Their only son, Henry Cadwallader Adams, took holy orders. The Martins’ second daughter, Anna, never married, and died, like her mother, at Bath, in 1867, aged 73.

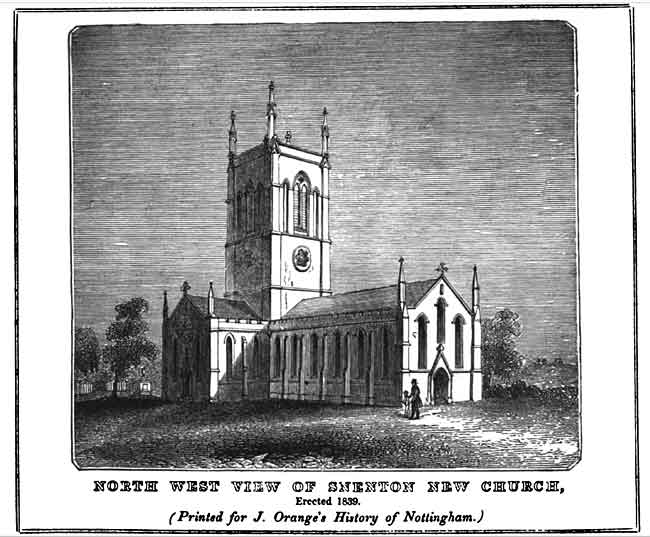

I am only too conscious of the fact that, throughout this story, Thomas Martin has been an elusive figure: what we know of him is the shadow, not the substance. A final mystery is how he, with his baby son, came to be buried at Sneinton. His brother Samuel was buried in St. Peter's, the church of which he was rector - Thomas Martin had been a witness at his wedding at that church in February 1769. The rector’s children were baptised, as were Thomas Martin’s, at St. Mary’s. There was thus no traceable family connection with Sneinton church. The old town churchyards, however, were becoming overcrowded, and at least one substantial Nottingham contemporary of Martin purchased a vault at Sneinton, on account of its picturesque situation, and because of his dislike of the idea of being buried in a town. Perhaps a similar motive prompted Thomas Martin to acquire a plot at Sneinton. The church beside which he was buried was still the tiny, much-patched mediaeval building which, according to William Stretton: 'Being in a state of ruin was taken down in 1809 and rebuilt on the old foundations 40 feet long and 21 feet wide... ' This second church, of brick, was far too small for a growing Sneinton, and was itself superseded in 1839 by the building whose tower still survives. The remainder of the church, however, was completely rebuilt just before the Great War. Thomas Martin would find little that he recognised in the church, or the Sneinton, of 1992.

THE CHURCH BUILT AT SNEINTON IN 1839, as depicted in James Orange's 'History of Nottingham'. It is possible that the monument immediately to the left of the church is intended to represent the Martin memorial. The drawing is, however, indifferent, and no railings are shown.

THE CHURCH BUILT AT SNEINTON IN 1839, as depicted in James Orange's 'History of Nottingham'. It is possible that the monument immediately to the left of the church is intended to represent the Martin memorial. The drawing is, however, indifferent, and no railings are shown.I AM GRATEFUL to Michael Brook for telling me of the whereabouts of the Cropper manuscripts, and to the staff of the Department of Manuscripts, Nottingham University (especially John Briggs) for their help in making these available to me. Pat Clark of Sheffield Local Studies Library gave valuable information on the Sheffield mill; and my brother, Peter Best, kindly sought out the Martin family history in the British Library, sending me relevant photocopies. As always, the staff at Nottinghamshire Archives Office, and Nottinghamshire County Local Studies Library, were hospitable and helpful.

The following published items were of particular value to me in researching this article:-

Nottingham Journal: 1771, 1795

Chapman, Stanley D.: Business history from insurance policy registers. (In: Business Archives, 32, June 1970)

Chapman, Stanley D. The early factory masters. 1970

Henstock, Adrian (ed.): The diary of Abigail Gawthern of Nottingham 1751-1810. 1980

Martin, Stapleton: History of the Martin family. 1908

Phillimore, W.P.W.: County pedigrees:Nottinghamshire. 1910

< Previous