< Previous

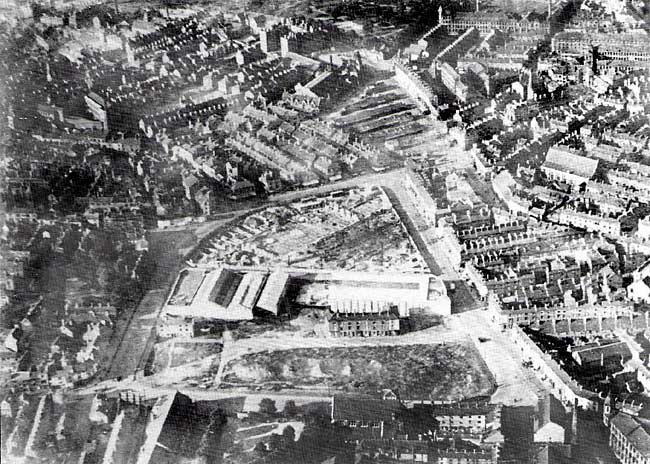

SNEINTON FROM THE AIR:

A view from the Twenties

By Stephen Best

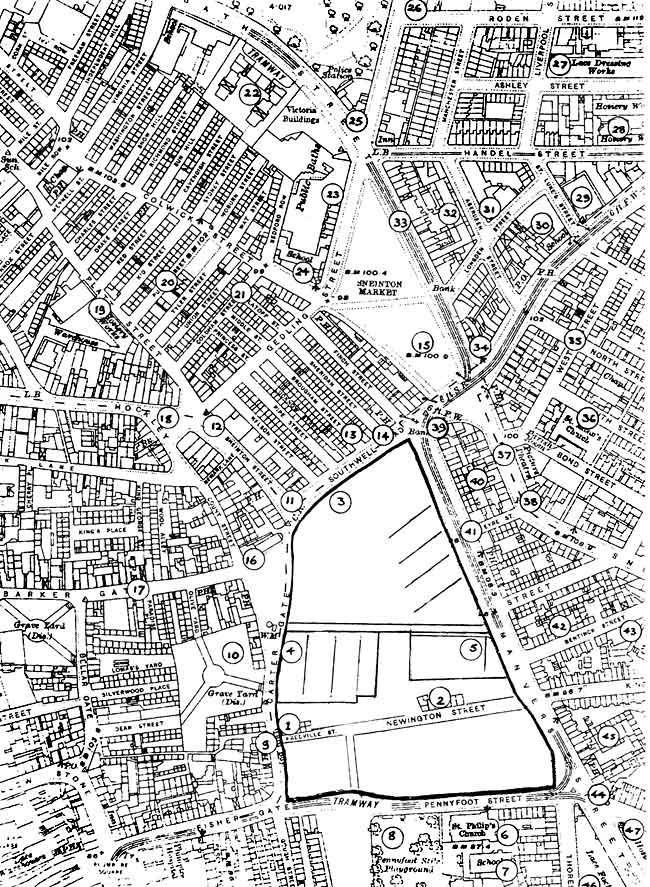

BRACKETED NUMBERS in this Article refer to the streetmap at the end.

Picture: Courtesy of Nottinghamshire County Council Local Studies Library.

Picture: Courtesy of Nottinghamshire County Council Local Studies Library.AS FAR AS I AM AWARE, the first aerial photographs of Nottingham were taken just after the Great War. They reveal so much, that one is given to vain regrets that such views were not possible in earlier times. We should, however, be grateful that the value of photography from the air was appreciated locally by the 1920s; pictures from that decade show, in fascinating detail, a Nottingham that has, in places, changed almost out of recognition.

The photograph reproduced here dates from about 1926, and was taken from an aircraft above Poplar Street, Sneinton. Though much has disappeared in the intervening sixty-odd years, there remain a few landmarks which survive today, enabling us to get our bearings and compare this scene with the Nottingham of 1992. What the camera shows is a predominantly 19th century town, much of it dating from the early part of that century, though a number of important mid and late Victorian buildings are to be seen. In 1926, however, significant change is beginning to take place.

The central feature of the scene is the area once known to the authorities as the Carter Gate/Manvers Street Unhealthy Area, a warren of early nineteenth century streets and courts, which was entirely cleared after the First World War. In the photograph, all the old property has been pulled down, with the exception of two rows of houses in Fredville Street (1) and Newington Street (2). I understand that the reason for their lingering on, empty and derelict, was the council's failure to discover the identity of the owners, and consequent inability to serve compulsory purchase orders on them. Fredville Street, incidentally, took its curious name from the Kent estate of the Banks family, into which John Plumptre of Nottingham married in 1756. From that date, the Plumptres lived at Fredville, ending their occupancy of Plumptre House, their mansion close by St Mary's Church.

At the far end of the site, work is going ahead at the Nottingham Corporation tram and bus depot and offices (3) while two new buildings have already been erected. On the left are the two premises of the Carter Gate Motor Co (4), opened in 1921, while to the right, at the comer of Stanhope Street and Manvers Street, stands the Trent bus garage (5), which came into use in March 1926, and was handed over to Nottingham City Transport in 1933. As seen here, therefore, it is a very new building indeed. I cannot be certain, but I think that a single-deck bus, with a white roof, is pulling out from the garage into Manvers Street.

At the foot of the picture, south of the cleared area, runs Pennyfoot Street, with St Philip's Church prominent (6). The church had been consecrated in 1879 as a memorial to the lace manufacturer Thomas Adams, who had died six years earlier. Much of the population of St Philip's parish had been lost with the demolition of the Carter Gate Unhealthy Area, but, by the mid-1920s, St Philip's had acquired the parish of St Luke's, when the church of that name in Carlton Road was closed - more of this later. St Philip's was to remain open until 1963, largely because of the long and dogged incumbency of the Rev John Goulton. Its site is occupied, at the time of writing, by Boots car park. The photograph also shows St Philip's Schools (7), and, to the west of the church, the Pennyfoot Street Recreation Ground (8), remembered by many people in the locality as 'Cottee Park'. This was opened in 1906, after the Parks Committee of Nottingham City Council had spent £500 in improving a piece of waste ground at the comer of Plough Lane. Local school children were trooped down to the park, and there presented with a bun and an orange. Sustained by these treats, they listened to the inaugural speech of Councillor Carey, the committee chairman, who urged them to take good care of the park. Juvenile residents -indeed, all residents - and park have long since vanished from the neighbourhood.

Moving clockwise around the clearance area, we turn right, across the end of Fisher Gate, into Carter Gate. Across the road from the abandoned back-to-back houses in Fredville Street is the Nottingham Castle public house (9), whose modern successor, uninspiringly named 'The Castle', today stands a yard or two away, in what is now Lower Parliament Street. Just above the pub are the trees which mark the disused burial ground (10), one of the three which existed in, or very close to, Barker Gate. Of these, 'Top Bury' survives as a rest garden, lying between Barker Gate and Woolpack Lane. On a sunny day it is a pleasant place, and some of its gravestones are worth a second glance. The site of 'Middle Bury' is the corner of Bellar Gate and Barker Gate; one or two dilapidated gravestones can still be found, leaning against the wall by the gateway to the old St Mary's Schools. 'Bottom Bury', the one in the photograph, now lies beneath the Ice Stadium car park.

Not long after the photographer took to the skies above Sneinton, the widening and extension of Lower Parliament Street cut a huge swathe through the street pattern of this part of Nottingham, wiping out St John Street, Cur Lane, Platt Street and Sneinton Street. In our view, however, the old approaches to Sneinton survive, and are not terribly easy to pick out. The narrow entrance of Sneinton Street can be seen, a little to the right of the row of hoardings: at the corner of this thoroughfare there stands, as it does still, Price and Beal's gentlemen's outfitters shop (11), its sun blinds outspread. As I write, the shop has been closed down for almost a year, but the building is recognisably the one in the photograph. Beyond Price and Beal's, in a row of shops brightly lit by the sun, is Pullman's celebrated drapery emporium (12) on the corner of Gedling Street. Other business premises on this side of Sneinton Street in the 1920s included Poyser's the jewellers, and Kiddier's brush manufactory. Pullman's lasted into comparatively recent years, and one could wish that the depressingly anonymous structure now occupying this site had half the character of what was pulled down to make way for it.

To the cast of Sneinton Street lies a tract of streets (13) which, by 1926, formed one of Nottingham's worst remaining areas of substandard housing. Nelson, Pipe, Lucknow, Brougham, Sheridan and Finch Streets were not to disappear until the mid-1930s, to be replaced by the new Sneinton Wholesale Market. The aerial view clearly shows this densely populated district, which consisted almost entirely of back-to-back houses. Those residents whose only windows looked out into the extremely narrow Lucknow Street had a particularly bleak prospect. Only one building survives in 1992, the Peggers' Inn (14), then the Fox and Grapes, which can be spotted here on the Southwell Road frontage: it is the building almost opposite the end of Manvers Street, displaying no sun blinds. Other businesses in Southwell Road at the time included William Taylor, pawnbroker; the British and Argentine Meat Co, butchers; and Marsden's, the grocers. To the right of Finch Street is the sorry array of ramshackle sheds which, at this time, comprised the wholesale market (15). As related many times in Sneinton Magazine, complaints had been voiced about the inadequacy of the market from the time it was moved here at the turn of the century, but it was not until the demolition of the adjacent streets, in 1934, that it became possible to rehouse the market in hygienic modern buildings.

Retracing our steps along Southwell Road, we come again to the hoardings opposite the emergent tram and bus depot. These mark the site of the Old Stag and Hounds pub at the corner of Count Street and Barker Gate (16). The latter street rises towards the left hand edge of the photograph, where the Old Cricket Players public house (17) can be seen. Count Street runs away from the camera, towards the bottom of Hockley. It was named after Count Paravicini, an Italian who is believed to have established a glass works near by. Badder and Peat's map of 1744, shortly after the Count's death, shows the street as Paravicini's Row, and the variation, Palavicini's Row, also appeared. Not surprisingly, Nottingham tongues had trouble in coping with such an exotic mouthful: the Borough Records for 1780, for instance, include a reference to 'Palamay Seney Row'. The townspeople, however, found a way out of this difficulty, and the thoroughfare became the more prosaic Count Street. The row of shops visible on the north side of Hockley (18) were all pulled down a few years after the photograph was taken, to be replaced by the buildings which stand there today.

Behind Hockley is the complex of factories situated between Coalpit Lane and Platt Street. They still survive; the tallest of them, Lambert's Factory, housed in 1926 the firms of Edward Ross and Son, hosiery manufacturers; and Albert Mather and Co, lace merchants (19). As 122-124 Lower Parliament Street, this building is now occupied by Morley and Kemp Ltd, lingerie manufacturers. To the east of the factory is an empty space, showing where demolition has taken place in Kid Street, Pump Street and Tyler Street (20). This part of Nottingham, the Meadow Platts, was one of the earliest areas of industrial housing in the town, which between 1740 and 1800 saw its population rise from about 10,000 to almost 29,000, with virtually no increase in its acreage. With land at such a premium, dwellings were squeezed in as economically as possible: back-to-back houses in narrow streets and alleys, and mean courts. All was appallingly insanitary, and it comes as no surprise to learn that the Meadow Platts was visited by cholera in 1832. Kid Street, by the way, was the scene, in 1845, of William Booth's first sermon. The long rows of roofs and chimneys next to the demolition area belong to houses in Tyler Street, Union Street and Coldham Street (21). To the right of these streets can be seen Colwick Street (now Brook Street), beyond which is another tightly-packed area of housing, leading up to Bath Street. All of this was redeveloped in the years following the taking of the photograph.

Two familiar landmarks are visible at the top of the view: Bath Street school and, next door to it, Victoria Buildings (22). The school, now an annexe of Arnold and Carlton College of Further Education, was opened in 1874; the first new school built by the Nottingham School Board, it had accommodation for 850 children. Victoria Buildings, now refurbished, and renamed Park View (rather, one feels, as Narrow Marsh was renamed Cliff Road), saw its first tenants in 1877, as Nottingham's first block of municipal dwellings. Nearer the camera are Victorian Baths (23): these were re-opened in 1896, a rebuilding of the Gedling Street baths of 1850, which originally possessed an open-air 'plunge' bath, 102 feet by 44 feet. At the corner of Gedling Street and Colwick Street stands the former Town Mission Ragged School (24) at the time of our picture Colwick Street Council School, a 'public elementary school, mixed'. Already condemned as a school, in 1924, it would continue in this role until 1931. At this time of writing, the building is in parlous condition, after a period of disgraceful neglect, and awaits a survey which will determine whether or not it can be saved.

Across the road from the Bath clock is the old Bath Street Police Station (25); its inspector in charge in the mid 1920s was the celebrated George William Downes, later Deputy Chief Constable of Nottingham. This building was replaced by a modern, singlestorey, police station, which, like others in and around Sneinton, was closed, amid general regret. For a while it housed a cafe, but is now a betting shop. A little way along Robin Hood Street, and facing Victoria Park, is the splendid industrial building which has for years been Bancroft's factory (26). This firm of blouse manufacturers were not the original occupants, the premises being built in 1869 for the Nottingham silk throwster William Windley, whose initials are carved below the unusual wind direction indicator which adorns the factory. As we shall presently see, Bancroft's did not have to move very far to come to Robin Hood Street. The long side elevation of Bancroft's factory stretches along Roden Street, and further along that street, on the right hand edge of our picture, rises another large textile factory. Lying between Roden Street and Ashley Street, this was known as Young's Lace Dressing Rooms (27). In 1926, it accommodated four firms of Lace dressers; C Eden & Co: H E Matthews & Co: Henry Wood & Son: and Spencer & Stevens. In front of this, facing on to Handel Street, can be seen one of I & R Morley's hosiery factories (28).

Below these factories, and bordering on Carlton Road, we came to a small open space (29) which provides one of the best clues to the date of the photograph. Here formerly stood St Luke's parish church, consecrated in 1863, and closed in November 1924.

Demolition began in October 1925, the parish being united with St Philip's, as already mentioned. A new building for the Nottingham City Mission was erected on the site, and still stands at the corner of St Luke's Street and Carlton Road. During August 1926, the Nottingham Guardian published an artist's impression of the proposed building, and the Mission was opened in the following May. We are, I think, justified in assuming the photograph to date from 1926. Just to the left of the St Luke's site can be seen the tall chimney above the boiler house of Knitters & Weavers Ltd, and Ashforth Hosiery Co. Ltd, in Longden Street (30). The area between this and Handel Street is nowadays a car park, useful but featureless; the photograph, though, shows several interesting buildings here. At the corner of Aberdeen Street is the Salvation Army Industrial Home and Poor Man's Hostel (31), built as a hosiery factory. Next door, abutting on to Handel Street, are the premises of the Nottingham Braid Co. Ltd. On the left hand side of Aberdeen Street, behind the row of shops in Bath Street, rises another prominent textile factory (32). Empty by the 1920s, this had a decade or so earlier been the location of the Nottingham Making-Up Co., blouse manufacturers, and of our old acquaintances W Bancroft & Co, 'frilling manufacturers'.

In Bath Street itself, the row of shops (33) facing the market looks much as it does today, with the little dome of the bank clearly visible at the end of Longden Street. Near it, in Bath Street, are a couple of electric trams, while, at the corner of Bath Street and Carlton Road stands the Albion public house (34). The side of Carlton Road facing the Albion is lined with old properties, many of them with thirty years or more ahead of them. Lying behind these is a densely built up part of New Sneinton. West Street (35) runs parallel to Carlton Road, with Bond Street, South Street, and North Street off it. Rising proudly above the housetops, as its architect intended, is St Alban's church (36), in 1926 still a parish church. Close by, on the bend near the bottom of Sneinton Road, can be seen the wide roof of the Palace Cinema (37). Opened in 1913, it was, by all accounts, already becoming a little seedy by the middle 1920s. Put in the shade by newer, more attractive, cinemas, it was to flicker out in 1945, the building surviving for over a decade in a variety of commercial uses, latterly as Leyland Office Furniture. A couple of doors above the Palace, and gleaming white in the sun, is the Windsor Castle pub (38). Not one old building today survives on the east side of Sneinton Road, and the picture clearly shows the old houses and shops which have been lost. On the other hand, the block bounded by Sneinton Road, Eyre Street, Manvers Street, and Carlton Road still exists in 1992, though some buildings in the photograph have gone, while others have undergone alteration. From the air, the Westminster Bank overlooking the market (39), and the motor garage of Claringburn and Codd, (now Nottingham Tyre Services), can plainly be seen (40).

Eyre Street, narrower here than it has lately become, is lined on either side with houses, with the King William IV pub at its lower end, facing Morley's pawnbroking establishment (41). Between Manvers Street and Sneinton Road is another tightly packed mass of early nineteenth century housing: some of this would go before the Second World War, though much was to last until the late 1950s. Between Eyre Street and the camera, Pierrepont Street, Bentinck Street, and Kingston Street run down to Manvers Street, all fronted by three-storey houses. Off Bentinck Street (opposite the Trent garage) can be seen more houses, squashed in courts and yards between the streets (42). Just visible, at the end of the low row of houses in Kingston Street, is the back of the Albion Chapel (43). Like St Alban's, the Albion is here seen rising above the roofs surrounding it, making a far greater impact on the townscape than it does today, as it cowers beneath the tower blocks, its scale thoroughly diminished.

More little shops line Manvers Street; the stretch between Kingston and Newark streets here includes such well-remembered ones as Redmile's bicycle shop. At the corner of Newark Street is the Duke of Wellington pub (44), with the Crystal Palace next door but one. In front of the latter public house, the tramlines sweep round the corner into Pennyfoot Street. Trams would remain a feature of Nottingham until 1936. Behind Manvers Street, in, I think, Crystal Palace Yard, and reached through an archway in the frontage, is a large building shown up prominently by the camera (45), whose identity has so far proved elusive. It is hoped that a reader will come forward to shed light on it.

We have now reached the bottom right hand corner of the photograph, and have come almost to the end of this aerial exploration. In the angle between Thoresby Street and Manvers Street stands Hill's Factory (46), complete with its tall chimney; during the 1920s it was tenanted by Edwin Mellor & Co, plain net lace manufacturers. Across Manvers Street is I & R Morley's Sneinton hosiery factory (47). As seen here, it is as rebuilt after the disastrous fire of 1874, and as it looked until another fire: the air raid of May 8/9 1941.

This photograph is not an exceptional one in any technical sense. It was, no doubt, all part of the day's work for the pilot and photographer employed by Surrey Flying Services. In all probability they went home for dinner, soon forgetting their brief flight over what must have appeared a fairly unprepossessing part of Nottingham. They might have been surprised (and, perhaps, pleased) to learn that, two thirds of a century later, so much juice could be squeezed from one of their pictures.

< Previous