< Previous

'A WATERY GRAVE' :

Sneinton and Nottingham links with Grace Darling and the wreck of the Forfarshire

By Stephen Best

THE WRECK OF THE FORFARSHIRE, showing the Darlings rowing out to the stricken vessel;

THE WRECK OF THE FORFARSHIRE, showing the Darlings rowing out to the stricken vessel;from a painting by Carmichael and Parker.

Many people will be familiar with the story of Grace Darling. The twenty- two year old daughter of the keeper of the Longstone lighthouse in the Fame Islands, off Northumberland, she helped her father save the lives of nine survivors from the wreck of the steamship Forfarshire, on the night of September 7 1838.

This disaster had interested me ever since I first saw the memorial, in Nottingham General Cemetery, to Daft Smith Churchill, hosier of St Mary's Gate, who lost his life in the wreck. Not long ago on holiday in Northumberland, and visiting the Grace Darling Museum at Bamburgh, I took with me photographs of the Churchill monument, for the Museum collection. During conversation with the curator, it was agreed that contemporary reports from Nottingham newspapers might be of interest to the Museum. In searching for these I found, not only the expected accounts of the disaster, and of Mr Churchill's death, but also a surprising Sneinton echo of the loss of the Forfarshire.

The background must be briefly sketched in. The Forfarshire, then just four years old, was a paddle-steamer, also carrying sail. Plying regularly as a packet ship between Hull and Dundee, she was capable of a speed of eight or nine knots with 400 tons of cargo on board. For the best class of passenger, the ship was quite luxuriously appointed; ladies' and gentlemen's cabins: private staterooms: marble mantelpieces in the saloons: painted panels by Horatio McCulloch, a well-known artist of the time. Daft Smith Churchill, with two acquaintances from Glasgow, sailed in her from Hull on September 5 1838 - note that this was the quickest way for a Nottingham merchant to reach the eastern side of Scotland. Churchill had without doubt engaged one of the main cabins, at a cost of £1.5.0d (£1.25p). According to a contemporary handbill, he would, while aboard, have been able to obtain: 'Provisions, wines and spirits on very moderate terms'.

On this last voyage, the Forfarshire carried a cargo of 'superfine cloths, hardware, soap, boiler-plates, and spinning-gear', and conveyed some thirty- nine passengers. Trouble was soon experienced with the boilers, a leak eventually causing a total loss of steam. Off St. Abb's Head, Berwickshire, the engines failed altogether, the vessel beginning to drift south in a strong gale and cold, blinding rain. The captain set fore and aft sails, intending to run before the wind and bring the Forfarshire into the shelter of Inner Farne. Missing his course, however, he struck the Big Harcar rock (then spelt Harker), some eight hundred yards from the Longstone light. The ship's starboard boat immediately put off with nine people aboard, including the mate; against all odds, they were picked up by another vessel, and landed safely at Shields. A quarter of an hour later, the wrecked Forfarshire broke in half just aft of her paddle boxes, the after-end of the ship being swept away with the cabin passengers, the master, and his wife.

GRACE DARLING, from a painting by Thomas Musgrove Joy.

GRACE DARLING, from a painting by Thomas Musgrove Joy.At about 4.45 am, not long before sunrise, Grace Darling saw the wreckage from her bedroom window in the lighthouse; the forward part of the ship, which included the foremast, funnel, and paddles, was jammed on the reef. Two hours later, after continuous searches with the aid of a telescope, survivors were spotted on the rock. William Darling thought it impossible that either the Bamburgh or North Sunderland lifeboats could set out in such conditions, resolving to row to the wreck with the help of his daughter, in a coble twenty-one feet long. In rough weather, three men were normally needed to work the boat. To avoid the very worst of the storm and the seas, the Darlings were obliged to row a circuitous course of about a mile to the Big Harcar. There they found nine survivors clinging to the rock, one holding her two dead children in her arms: another, a clergyman, was dead when they arrived. William and Grace Darling took off five people at the first attempt, William then making a second trip to collect the remaining four, assisted by two members of the Forfarshire's crew, just rescued.

A very prejudiced inquest, at which important witnesses were not heard, found that the ship had been wrecked through its captain's negligence, and imperfections of its boilers. Toward the end of the month, though, another inquest was held, on a member of the crew whose body was found at sea: this time a reasonable conclusion was reached, that the loss of the vessel was due to tempestuous weather. There was no passenger-list for the Forfarshire, but it was generally accepted that forty-three people in all had lost their lives in the disaster.

William Darling evidently felt that he had done no more than his duty; nonetheless, Grace Darling very soon found herself a national heroine. Boatloads of curious sightseers sailed to the Farne Islands to catch a glimpse of her; all kinds of unexpected communications reached her; requests for locks of her hair: offers to appear on the London stage and in a circus: proposals of marriage. Public subscriptions were opened for her in various towns. The Duke of Northumberland took a kindly interest in her welfare, while Queen Victoria, then only nineteen, was greatly moved by her story. Medals were presented to the Darlings, and Grace was depicted on mugs, plates, and china figures. Poets of every degree, from Wordsworth down, composed verses to commemorate her bravery. Grace Darling continued to live on the Longstone, pestered by the inquisitive. None of the Darlings seems greatly to have enjoyed the publicity surrounding them, some of the tales told being so exaggerated that much ill feeling was engendered locally. Grace remained a celebrity for the rest of her short life, dying of tuberculosis, aged only 26, on October 20 1842, a little over four years after the loss of the Forfarshire.

We now turn to the Nottingham newspapers of 1838. The Nottingham Review and Nottingham Journal of September 21 each printed a death notice of Mr Churchill. The Journal's long news story about the wreck and inquest ended thus: We regret to announce that our respected townsman, Mr Daft Smith Churchill, was among those who met, by this distressing event, a watery grave: the body has not been found.' On October 12, however, the Journal had to announce that: 'The body of our towns-man, Mr D. S. Churchill, who was drowned at the wreck of the Forfarshire steam-boat, has been washed ashore at North Shields: it was identified by the marks on his linen. He had on his shirt, trousers, and boots.' A week later, both local papers reported Churchill's funeral, the Nottingham Review giving the more complete account of the course of events:

'Mr D. S. Churchill - The remains of this unfortunate gentleman, who was wrecked in the Forfarshire steam packet, were buried as soon as the coroner's inquest had been held upon them. His relatives in this town were unwilling to be deprived of the sad consolation of having his remains interred with the family, and therefore they caused the body to be exhumed, and it was brought to Nottingham, and interred with great privacy, in the new cemetery, at a very early hour, on Tuesday morning.' The new cemetery was Nottingham General Cemetery, and the Journal's report, also of October 19 1838, mentioned Daft Smith Churchill's role as a director of the cemetery: 'In the establishment and prosperity of which undertaking the lamented gentleman took, while living, a considerable part, and evinced a high interest. We understand that the directors of the Cemetery intend to erect amonument, or tablet, in some part of the grounds as an acknowledgement of the active and useful services of the deceased.' This was indeed set up in due course, and is the memorial referred to at the beginning of this article. An obelisk on a square base, it appears prominently in early views of the cemetery. It is reached by shallow steps from the main path, not far from the Canning Circus gate. The inscription, carved by the Nottingham mason Samuel Pratt, tells the sad story. It is worth quoting in full:

'To the memory

of

Daft Smith Churchill

of

Nottingham, Merchant,

Who was lost in the lamentable wreck of the

Forfarshire steam vessel

Off the coast of Northumberland In a heavy storm on the night of

September 7 A. D. 1838 At the age of 44 years.

His remains,

Washed on shore by the tide, Are interred in his family vault

In these grounds.

Resting in the hope Of a resurrection To a blissful immortality.

This monument

Was raised by the Directors of the

Nottingham General Cemetery As a testimonial of their gratitude

For his successful and valuable services In its formation,

And as a tribute of their respect For his character,

And their deep regret for his sudden And melancholy death.

Watch, therefore, for ye

Know neither the day Nor the hour wherein

The Son of Man cometh.

Saint Matthew, Chapter 25, Verse 13.'

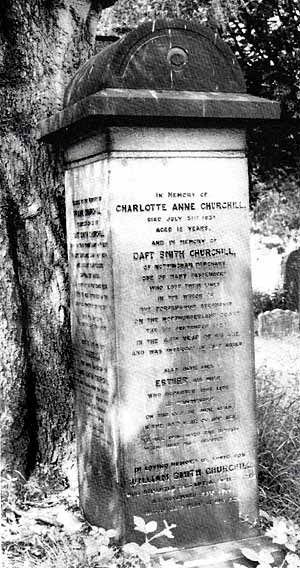

THE MEMORIAL OBELISK to Daft Smith Churchill erected by his fellow-directors of Nottingham General Cemetery. (Photo: Stephen Best).

THE MEMORIAL OBELISK to Daft Smith Churchill erected by his fellow-directors of Nottingham General Cemetery. (Photo: Stephen Best).Daft Smith Churchill's actual place of burial is his family vault, about two hundred yards away from the memorial put up by his fellow directors. A tall, square, column, with a top shaped like a halfcylinder, it bears inscriptions in memory of Mr Churchill, his wife Esther, and their children. These were Charlotte Anne, Isabella, and Sarah; and William Smith, Frank, and Joseph Fleetwood, the last two of whom died in South Africa. In his will, drawn up in 1834, Daft Smith Churchill had left his wife £100, and all his household goods, furniture, plate, china, linen, 'and other moveables'. He had instructed his executors to dispose of his business and real estate, and to invest the proceeds so as to provide Mrs Churchill with an income of £300 a year of her own, and with money to help her bring up the children.

After this lengthy preamble it is time (high time, the reader may be thinking) to introduce the Sneinton connection with Grace Darling. First intimation of this comes in a letter printed in both the Nottingham Journal and Nottingham Review of October 12 1838, and the Nottingham Mercury of October 13: 'Sir - As subscriptions are being raised, both in Nottingham and Snenton, to present some memorial of admiration and gratitude to Miss Grace Horsley Darling, daughter of Mr Darling, of Outer Fern light-house, by whose noble daring nine of the sufferers in the wreck of the Forfarshire were snatched from a watery grave, perhaps you will allow me to call public attention to the circumstances, by the insertion (this week) of the following verses:-

Yours respectfully,

T.R. Snenton, October 1838.'

Of the verses, more will be said later. It is interesting, though, to learn that not only did Nottingham join in the national outburst of sentiment in recognizing Grace Darling's bravery, but that even Sneinton (or rather, some of its inhabitants) decided independently to raise a collection for her. The spelling of place names is perfectly correct; at this date the Farne Islands were often called the Fern Islands, and the forms Sneinton and Snenton were both in use.

The writer of the letter, Thomas Ragg of Haywood Street, Sneinton, deserves more than passing mention. Remarkable son of a notable father, he was bom in Nottingham in 1808. His father, George Ragg, also a native of the town, moved to Birmingham to open a bookshop when Thomas was a baby. Ragg senior also had business interests in lace and hosiery, but was brought to financial ruin through his political activities. A leading radical, he was sent to prison in 1820 for selling a newspaper called the Republican, and a year later received a 12-month sentence for publishing a 'seditious and blasphemous libel' in that paper. As a lad of ten, Thomas Ragg was removed from school, to work in the printing office of the Birmingham Argus, founded by his father. After about four years, however, he became apprenticed to an uncle, a Leicester hosier. This uncle moved to Nottingham, to establish a lace factory, and Thomas came with him, back to his birthplace. Eventually, however, the uncle came to feel that Thomas Ragg's literary work, and his studies, were occupying time that should have been devoted to the lace trade. Accordingly, in 1834, Thomas found a job as assistant at Dearden's bookshop and library, in Carlton Street. (The building is probably best known for its association with Bell's, the stationers: it now houses Sonny's Restaurant.) In 1832, Thomas Ragg had made an impassioned speech at the New Sneinton celebrations to mark the passing of the Reform Act, and had in the same year published his poem 'The Incarnation'. In early life an agnostic, Ragg became, in his twenties, a fervent Christian, writing a number of volumes of verse, all informed by his religious faith. 'The Incarnation' was merely a fragment of a much longer work, 'The Deity' (published by Dearden's which was in 1834 reviewed in The Times as 'a very remarkable production'. Ragg contributed poetry to the Nottingham Review, and in Dearden's Miscellany published a verse appeal on behalf of his fellow poet and Sneinton resident, the chronically hard-up framework-knitter Robert Millhouse. He received several offers of a university education; declining them, as a condition of acceptance was that he take holy orders. In 1839, Thomas Ragg left Sneinton, to become editor of the Birmingham Advertiser, a paper he briefly owned. Later he managed the Midland Monitor. When the Advertiser ceased publication, he went into business in Birmingham as a printer and stationer. His Christian verse continued to appear, and this brought him, at length, to the notice of George Murray, Bishop of Rochester, who in 1858 persuaded him to become ordained. Finding Ragg a curacy in Kent, the bishop paid his salary out of his own pocket. On Dr Murray's death, Thomas Ragg became curate of Malin's Lee, and, in 1865, perpetual curate of Lawley. Here he stayed until his death in 1881, survived by ten children of his two marriages. In his day his reputation as a poet was considerable, much critical attention focusing on the fact that a significant amount of his work was written while he was 'a self-educated mechanic' (Thomas Ragg is mentioned in Two Sneinton Men of Verse', and 'Now for Jacky Musters', in Sneinton Magazine, nos. 7 and 17 respectively).

Though he was to earn the tag, 'the adopted poet of the Evangelic muse', Ragg was, one feels, in poorish form when composing his Grace Darling verses; the kindest thing one can say is that he clearly meant well. The very nature of such topical, celebratory, verse, of course, rendered it a rush job. A few extracts will suffice to give a flavour of its tone and quality. Grace Darling wakes to see that:

'A vessel that had striven in vain

The storm's fierce wrath to brave,

Was dashed upon a jutting rock

By the hoarse growling wave.'

With her father, she goes to the assistance of the survivors:

'Undaunted by the sea and sky, In terrors wild arrayed.

The maiden fearless plies the oar, Her gallant sire to aid.

And lifted now on mountain waves, now borne to deeps below;

Still on they urge their fragile skiff To their dread scene of woe.'

Eventually, the rescue is successfully accomplished:

'Nine, nine, are snatch'd from perishing,

And sheltered safe from harm,

By the strength heroic virtue gave To one fair female arm.

Oh! man amid the storms of life

Oft nobly bears his part,

But what can care for human woe,

Like woman's dauntless heart?'

Anyone anxious to savour the other fifteen verses must seek them out in the Nottingham Journal or Review, of October 12 1838. That the papers printed Ragg's effusion in full, though, does emphasise just how strongly fervour for Grace Darling had gripped the country. Apart from those most intimately connected with the wreck of the Forfarshire, or living nearby on the Northumberland coast, people had come to hear about her almost entirely through newspaper reports (in Nottingham, weekly papers), or by broadside ballads and accounts sold by street traders. It all says much for the power of the press. Residents of Sneinton evidently responded very positively to the appeal, the three Nottingham papers reporting as follows on October 26 and 27: 'We are glad to learn, that the subscription raised in Sneinton for a memorial to Grace Darling and her parents, has been very successful. The present to Grace consists in a pictorial Bible, richly bound, and bearing the following inscription:-'To Grace Horsley Darling, the brave hearted girl, who in the morning of September the 7th, 1838, thought not of her own life, while assisting to save the lives of others, this book is presented by some of her admirers residing in the village of Sneinton, near Nottingham.' Mr Darling will receive an embossed silver mug, with his initial letter, and September the 7th, 1838, engraved on the shield; and Mrs Darling is to be presented with a silver cream jug, inscribed 'To the mother of Grace Darling'. These articles, we are informed, will be taken to the subscribers for their inspection, and will then lay a few days at the shop of Mr Dearden, previous to their being forwarded to their ultimate destination - the solitary light-house of Longstone Island.'

It will be noted that, while her parents were the recipients of silverware, Grace Darling had to be content with a Bible. This is in no way to disparage Holy Writ, with which, by all accounts, Grace, a devout, well-read young woman, had been familiar from her childhood. One may suspect, however, that by the time all the tributes had rolled in, she had more Bibles than she knew what to do with. The fact that the gifts went on public view at Dearden's, Thomas Ragg's place of work, suggests that the Sneinton poet had a hand in organising the subscription. These presents are not to be found in the Grace Darling Museum today, but ample opportunity must have existed for the loss or dispersal of Darling family possessions, in the century between the wreck of the Forfarshire and the opening of the Museum. Proof of their arrival in the Farne Islands appeared in the Nottingham Mercury of December 15 1838:

'GRACE DARLING

The following letter from Grace Darling, acknowledging the receipt of the Sneinton presents, has been received by Mrs Sterland:-

Longstone Lighthouse, 24th Nov, 1838

Dear Madam - I own the receipt of yours of the 2nd instant, which has been delivered to me by Robert Smeddle, Esq. of Bambro' Castle, and in reply, I am requested by my dear father and mother to thank you, also the other ladies and gentlemen individually, for their very kind present; for myself, dear Madame, I am quite at a loss in what way to return you a suitable answer. Had your valuable present not been associated with such a melancholy occurrence, I might have said I am delighted with it, but I must beg leave to say that the awful loss of life caused by the loss of the Forfarshire debars me of that pleasure. Through you, dear Madam, I most respectfully tender my best thanks to the ladies and gentlemen who have been so kind to me on the present occasion. Believe me, I sincerely feel for the loss you have sustained, but I trust your loss will be your friend's eternal gain. To the Rev. Mr Pickering, I have to return my grateful thanks for the very kind advice contained in his letter, and I trust by God's assistance I may be enabled to profit by it; may I most humbly beg the favour of the Rev. Gentleman, to make mention of me at a throne of Grace.

My dear Madam,

Your very humble servant, Grace Horsley Darling

P.S. I trust you will avail yourself of the first opportunity of visiting our humble abode, where, be assured you will receive a hearty welcome. I have enclosed a little of my hair and a pocket handkerchief, which you will please to accept of, and likewise a handkerchief which you will please to present to the Rev. Mr Pickering. It has been exceeding bad weather, otherwise this would have been forwarded sooner.'

The solemnity and piety of this letter appear to have been characteristic of Grace Darling's replies to well-wishers. One written by her in response to a Glasgow presentation, and reprinted in the Nottingham press, certainly rivals it in seriousness. It comes as something of a relief to find Grace commenting on the weather. After an inconclusive search, I have tentatively identified the recipient of the letter as the wife of Octavius Sterland, 'gentleman', of Notintone Place, formerly in business for many years as a chemist and druggist in Nottingham. He had been an Overseer of the Poor of St Mary's parish, and was a trustee of Wartnaby's Almshouses, Mrs Sterland had evidently lost a friend in the wreck of the Forfarshire; it must be probable, though by no means certain, that this was Daft Smith Churchill. The Reverend W. Pickering was a Baptist minister, and a neighbour of Thomas Ragg in Haywood Street. It seems unlikely that Mrs Sterland, Mr Pickering, or any of the Sneinton contributors, ever found a convenient opportunity of dropping in at the Darlings' 'humble abode', situated as it was on an inhospitable rock, several miles out in the North Sea, some 250 miles away from Nottingham.

Examination of Nottingham newspapers to the end of 1838 has failed to find any further information about the Nottingham collection for Grace Darling. She was however, by no means forgotten by the press here. On November 23, the Review printed another poem: 'To Grace Horsley Darling', by one Eleanora Louisa Montagu. It consisted of five verses, of which this is an example:-

'I see thee in thy rock-built home, swept by the dashing seas,

I hear that voice as on that night it stilled the rushing breeze;

When stirred by heavenly visions, thou didst burst the bounds of sleep,

To take thy place in peril's path - The Angel of the Deep.'

One doubts whether the Darlings would have described the appalling storm of September 7 as a 'rushing breeze', but it is only too easy to make merry, a century and a half afterwards, with these sincere sentiments; it has to be said that even Wordsworth's poetic offering to Grace Darling was not much better. Near the end of the year, on December 21, the Review reported the visit of Grace and Mr Darling to Alnwick Castle, seat of the Duke of Northumberland; the 52 year-old William Darling was described as 'her venerable father'.

THE COMMEMORATIVE STONE above the Churchill family vault in Nottingham General Cemetery. (Photo: Stephen Best).

THE COMMEMORATIVE STONE above the Churchill family vault in Nottingham General Cemetery. (Photo: Stephen Best).It is possible today to visit the Farne Islands by boat from the nearby fishing village of Seahouses. The Longstone, a bare rock, is the outermost of the islands proper, some five miles offshore. The lighthouse, former home of Grace Darling, is still in operation; it has for a number of years been automatic, so the island nowadays is uninhabited. Close by is the Big Harcar, much of it submerged at high water. It is a bleak spot, and one's chief feeling is of boundless admiration for the Darlings, rowing their small boat as they did, in terrifying seas, bitter cold wind, and driving rain. (The fact that the North Sunderland lifeboat did, in the event, put out, reaching the Longstone soon after the Forfarshire survivors were safely landed there, in no way detracts from the superb courage of William and Grace Darling.) It is poignant, too, to consider Daft Smith Churchill, that comfortably-off Nottingham hosier, dying violently in this place unknown to him, and being washed ashore more than forty miles to the south. The pleasant, leafy surroundings of his memorial in Nottingham are in sharp contrast to the grimness and remoteness of the place at which he met his death.

I had hoped to include a portrait of Thomas Ragg among the illustrations to this article. Sadly, my unavailing search, including an enquiry at the National Portrait Gallery, leads me to suspect that this interesting man was never painted or photographed. It is possible that a picture of Ragg might have appeared in his autobiography, 'God's dealings with an Infidel, or Grace Triumphant', but I have been unable to locate a copy anywhere. The book is referred to in the Dictionary of National Biography, but even the British Library does not possess a copy.

< Previous