< Previous

SCUM AND RASCALITY:

How the racecourse came to Colwick

By Stephen Best

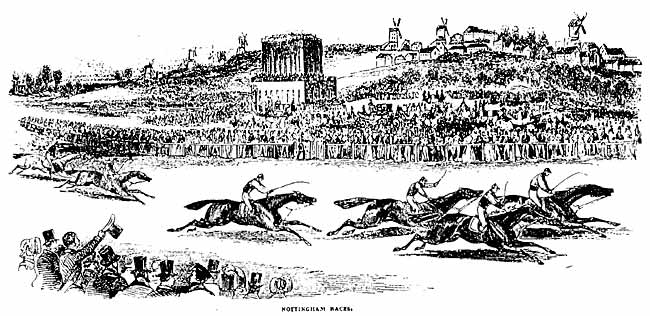

FOR JUST OVER A CENTURY, Nottingham's racecourse has been established at Colwick Park, almost on the doorstep of the Sneinton racegoer. Before the move to Colwick, however, Nottingham Races had, for some two hundred years, taken place on the Forest. As far back as the seventeenth century, a course of about four miles existed on the Forest and Basford Lings, the land to the north of the present-day Gregory Boulevard. Early in the following century, this circuit was reduced to one of two miles. An imposing grandstand, designed by John Carr of York, was built in 1777; this contained tea and card rooms, and a large entertainment room, while its roof offered five hundred standing spectators a splendid view of the racing. Parliamentary Inclosures in the 1790s almost destroyed this course, and the constricted nature of the site remaining necessitated the laying out of a figure-of-eight racecourse. This arrangement pleased nobody, onlookers finding it impossible to obtain a reasonable view of the races, and, in 1813, a new course was created: this time an elongated oval of a mile and a quarter.

With the passing of the Nottingham Inclosure Act of 1845, the Forest and grandstand became the property of Nottingham Corporation, which appointed a committee to oversee the conduct of the races. By the 1880s, the Nottingham meeting was in decline; the course was generally considered inadequate, being likened by one writer to a circus enclosure, while Nottingham was unable to offer prizes valuable enough to attract large entries, or sufficient horses of high quality. There were only four days' racing each year, two days each at the Spring and Autumn meetings. A further threat was the growing opposition in the town to the Corporation's having any part in the staging of horse-racing. As will be seen, this climate of opinion was eventually to put an end to racing on the Forest.

The proceedings of Nottingham Town Council, and the minute books of its committees, trace the final decline of racing under the Corporation. In 1886 the Race Committee was reappointed in the face of an amendment proposing its dissolution; while February 1887 brought an example of the behind-the-scenes arrangements necessary in putting on a race meeting. The Watch Committee sent in an account to the Race Committee, for the services of Borough Police detectives at the races. The Race Committee sharply replied that they engaged 'special detectives, acquainted with the work required at race meetings', and that ’such special detectives are quite adequate'. 1889 saw the future of the Forest racecourse under increased attack. On March 3, the Town Council received resolutions from the electors of Bridge Ward, and from members of Pleasant Sunday Afternoons meetings,, protesting against the appointment of the Race Committee. A motion that the committee be not reappointed after the current year, and that the land be appropriated to means of recreation other than racing, 'as they may deem best in the interests of the town', was only narrowly defeated in Council, by 30 votes to 27. The committee was duly reappointed in November, almost its first act being the donation of £10 to a Mr Smitherman, 'on account of the accident which happened to his children on the Forest, at the last races'.

1890 began quietly enough, with the Race Committee declining to let part of the racecourse enclosure to the Corinthian Tennis Club or the YMCA as a 'tennis ground'. In May, however, the cloud over Nottingham Races darkened appreciably. At a Town Council meeting on the 5th, Councillor Lee, seconded by Councillor Brownsword, put forward a motion. This urged the Council to allow no betting at any race meeting held under its management, and to abolish admission charges to any part of the ground. This, of course, was intended as a death blow to all racing on the Forest, the alterations proposed being certain to bring financial ruin to all concerned with staging the race meeting. A number of local pressure groups and organizations sent in memorials in support of Mr Lee's motion; these included Church of England clergymen in Nottingham: Nottingham Sunday School Union: the Men's Sunday Morning Institute, and the YMCA. In the event, an amendment was voted on, and passed, 'That after November 1st next, no Race Committee be appointed by this Council,' and that thereafter the control and management of the Forest be delegated to the Public Parks Committee'.

The two race meetings of 1890 took place as usual. Just before the Autumn Meeting, the Race Committee confirmed the admission charges; Stand and First Ring 7/6d (37½p): Second Ring 5/-: New Enclosure 2/-. Apart from those paying for entry into one of these enclosures, a view of the races was, as it had always been on the Forest, free. Top prize money, £500, was for the Nottinghamshire Handicap, while at the other end of the scale, A Hunters' Selling Flat Race offered only £50 in prize money. On this occasion entry fees for the latter race amounted to just £6, three entrants paying £2 each. Although no one knew it for certain, many people believed that this Nottingham Autumn meeting would bring down the curtain upon racing on the Forest. As the Evening Post put it: 'Amongst the residents of the town who met in the ring, speculation was rife as to whether this will be the last of the Nottingham meetings, and whether the Race Committee will be reappointed in November. This, however, is a topic which can afford to wait, and can better be discussed under calmer circumstances'. It will be noted that the Race Committee, despite the mortal blows it had sustained in Council, was taking a long time in dying. 'Bright and breezy' weather favoured the first day, whose main event was the Nottinghamshire Handicap: this was won by Glory Smitten, with the beguilingly named Tommy Tittlemouse second. Other races on the card bore recognisably local names; the Bestwood Nursery Plate: The Lenton Firs Selling Plate: the Bleasby Gorse Plate. September 30, the second and last day of the meeting, was suitably gloomy. 'The bright blue sky', observed the Daily Guardian, 'had given way to a dark, dull, and dismal canopy, and the atmosphere was close.' Chief race of the day was the Welbeck Abbey stakes, with a number of lesser races preceding it. The report of the Mile Nursery Plate included a mention of a now-forgotten racing landmark; this was 'the last turn at the corner of the Gregory Boulevard', where a horse named Nerissa lost the lead, eventually to finish last. The Welbeck Abbey stakes was won by Grecian Bend, from Spearmint, with Countess Therry third. Once again, there was a local flavour to the names of the races - the Little John Selling Plate: Friar Tuck Stakes: Sherwood Handicap Hurdle Race, and Cotgrave Gorse Plate. An indication of the dwindling status of Nottingham Races was, perhaps, provided by the poor entries for two of the races. Only two horses contested the Sherwood Handicap, while Danvita walked over in the Friar Tuck Stakes. The Cotgrave Gorse Plate was won by Mr T. Tyler's Sir Hamilton, whose jockey, A. Nightingale, was thus to have the melancholy distinction of riding the last winner on the Forest. Mr Nightingale, however, could not have known this as he passed the post; Nottingham was to see a winter of bruising argument before the Forest racecourse was officially wiped off the racing calendar.

The Race Committee met during October to approve payment of various accounts connected with the Autumn Meeting. These included £15.3.6d to George Brown, the catering contractor, and £11.5.0d to Stallon, Head & Dudley, 'London detectives' - presumably the experts whose attendance at the races had made the presence of the Borough detectives unnecessary. A further accident had occurred at this meeting, a Mr W. H. Brown being offered £6 as compensation for an injury to his boy on the Forest. The Autumn Meeting had made a profit of just £43.3.0d. On December 1, the Town Council received more memorials, 'praying the Council not to let or lease any portion of the Forest for horse racing'; the petitioners included Nottingham Women's Liberal Association, Nottingham Wesleyan Methodist Council, and the Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Classes for Men and Women. In what seems to have been an attempt to placate public opinion and, at the same time, leave the door open for the continuation of racing on the Forest, the chairman of the Public Parks Committee, Ald. Sir John Tumey, made this response. The Borough Engineer, Arthur Brown, was to be asked to prepare a plan, showing how the parts of the Forest currently used for racing could be made available for cricket, football, and other games, and to estimate how much such alterations would cost. Mr Brown wasted no time, and, by early January 1891, his report had been distributed to council members. There was, he said, a demand for increased cricket facilities on the Forest. If the space used for racing were to be made available for other games, considerable lengths of fencing would have to be removed. Brown further pointed out that the ground level of the racecourse was markedly higher than that of the surrounding playing fields areas, and that levelling the whole ground would involve the excavation of some 57,000 cubic yards of material. He recommended that, if this were done, earth from the racecourse should be used to fill in the football ground and raise its level. Mr Brown was anxious not to interfere with the fine turf on the cricket pitches; although about 7 acres would be added to the cricketing area, few extra games would be possible, as it was not safe to pitch wickets within forty yards of Gregory Boulevard or the Forest carriage drive. The work would cost about £7,000. After considering the Borough Engineer’s report, the Public Parks Committee made the following recommendations to the Council:-

' i) No part of the money reported as necessary be expended at the present time, ii) The Council keep the Forest in its present condition till construction of the M.S. & L.R. begin, iii) The Committee be authorised (until the railway be commenced) to let the race-course, grandstand, etc., as formerly.' A word must be said about the railway; the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (later the Great Central) was just embarking on the grand scheme for its London Extension. This was the line which was to involve the building of Victoria Station, and the carrying out of heavy tunnel and viaduct works through Nottingham. Mansfield Road tunnel, indeed, was eventually to run under the eastern end of the Forest, where the bowling greens now are. In 1890, however, it was uncertain what effect the projected line would have on that side of the Forest, and the future of that part of the ground was, therefore, in doubt.

So the battle lines were drawn up, and on January 26 1891 a special meeting of the Town Council was held at the Exchange, 'to consider the future of the racecourse on the Forest.' The Nottingham Daily Express remarked that the hall was unusually full, such a large crowd generally turning up only for a mayor-making. Like the other Nottingham newspapers, the Express reflected the enormous public interest in the matter by providing lavish coverage of the speeches delivered at this Council meeting. The Deputy Town Clerk opened proceedings with the news that no fewer than 108 memorials on the subject had been received, containing 11,191 signatures in all. The memorials, identically worded, lacked nothing in emphasis: '..... and whereas the majority of ratepayers, all religious and temperance bodies, and all concerned in the education of youth have already sufficiently indicated their sense of the evil brought upon the town by the holding of races under the Race Committee and whereas the proposal of the Public Parks Committee, whilst on its face intended to be temporary, would in reality tend to be permanent; and whereas the expenditure of a small sum would make the area of the racecourse an available playground, and there is no need at the present moment for the adoption of the scheme of the borough surveyor or approaching to it Your memorialists, therefore, urge that..... the connection, direct, or indirect, of the Corporation with the races should be completely severed, and the Forest restored in its entirety to its proper and legitimate purpose of serving at all times for the healthy recreation of all inhabitants of the borough. And your memorialists pray that the recommendation of the Public Parks Committee may not be adopted, and the races may not be permitted on public lands.' Among the churches of all denominations which had sent in memorials were St Philip's, Pennyfoot Street, and the Albion Chapel, Sneinton Road. A glance through the list of memorialists affords some idea of the variety and vigour of those organisations which sought to raise the moral tone of Nottingham in 1890 - the Pride of Village Lodge of Good Templars: Arnold Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Temperance Society: Young Men's Mutual Improvement Society: Rose of Sharon Tent of Rechabites: Nottingham Public Morale Council: Men's Sunday Morning Institute: Nottingham Temperance Mission: Morley Hall Society of Spiritualists.

Ald. William Lambert, J.P.

Ald. William Lambert, J.P.It is worth quoting at length from the ensuing debate, which included speeches of real fervour, and remains, in its way, a perfect example of Victorian municipal high-mindedness. Alderman Lambert1 of the famous firm of lace dresses and dyers, rose to move the adoption of the Parks Committee's recommendations; that no money be spent on the Forest, that the ground be left as it was, and that racing be continued for the time being. He observed that this took some courage, 'in the face of the vast number of petitions'. The races were, he said, 'virtually abolished', and the committee were only asking for the meetings to carry on for one year, or until the railway scheme was dealt with by Parliament. Any suggestion that this was a ploy by the Committee to get in the thin end of the wedge, and thus secure racing indefinitely, was, he said, a reflection on the honour of its members.

Mr. Frederick Acton, J.P.

Mr. Frederick Acton, J.P.Opposing the motion, Alderman Frederick Acton stressed the absolute inconsistency of the Corporation's appointing a Watch Committee, part of whose duty was the suppression of illegal practices on the turf, while, at the same time, electing a Race Committee to manage the races. Mr Acton, a solicitor, believed that the Borough Engineer had been set up as a 'bogie man', to frighten the public into thinking that it would cost £7,000 to adapt the Forest for any other use. As it stood, adoption of the Parks Committee report could allow the Committee to lease the racecourse for 21 years, or for ever, to any syndicate that wished to run the race meetings. The only part of the report that should be adopted, he said, was the recommendation not to spend any money upon the Forest, and this he urged. He did not make this amendment 'in any saintly or pharisaical spirit,' but nevertheless emphasised that in no other sports were found 'the same conglomeration of scum and rascality as they found connected with racing.' He hoped the Town Council would reject the report, and, 'as guardians of the moral and educational life of the municipality, would provide healthy recreation for the people.'

Councillor Samuel Brittle (another solicitor) disagreed. There was, he thought, nothing wrong with racing on the Forest. The working men of Nottingham had long been able to see their racing free of charge, and they should be considered in any decision to be arrived at. Councillor Robinson, in similar vein, wondered why 'what was right and proper in some parts of the country was disgraceful and degrading in Nottingham.' Another senior voice to call for the ending of racing on publicly-owned land, however, was that of Alderman Edward Gripper, chairman of the Nottingham Patent Brick Co., who held that race meetings benefited 'men outside, who came to Nottingham practically to prey upon their pockets'. Alderman Sir John Turney, chairman of the Trent Bridge firm of leather dressers, doubted whether anyone present detested racing more than he did, but suggested that it was wrong to single out racing on the Forest for suppression, while gambling was still rife on football matches played in public parks. This view was strenuously opposed by Coun. J.A.H. Green, the third solicitor to speak in the debate; at this time still under thirty, Green would eventually become Town Clerk of Nottingham. 'Did horse racing', he asked, 'exist for any purpose other than betting? When football and cricket pitches were laid out in the parks, were betting rings provided, as they were on the racecourse?' Mr Green claimed to have figures to prove that in the seven Board Schools nearest the Forest, the total drop in average attendance amounted to 626 in the Autumn Meeting week2, and 240 in the Spring. At the Voluntary Schools, too, a similar problem existed; St Mark's School had 101 out of 249 absent on the last day of the races, while between a third and a half of the scholars were missing from St Paul's School, Hyson Green, on the same day. Two members of the Public Parks Committee, Aldermen Lambert and Blackburn, repeated that the Committee had no plans to continue racing for more than one year at a time, and in any event only until it was known whether the M.S. & L.R. would require any part of the Forest. Opponents of the Committee knew this very well.

Unfortunately, the words 'for one year' had been omitted from the report. (Cries of 'Oh', and laughter, greeted this remark, Ald. Lambert angrily retorting that the laughter was an insult.) Despite these assurances, he lost the argument, Alderman Acton's amendment being approved by 34 votes to 22. No money was to be spent on extra cricket and football facilities on the Forest, but there was to be no more racing there. The death knell of horse-racing on the Forest was thus, after many false alarms, finally rung. The announcement of the vote was greeted with cheering from the back of the hall.

In its leading article of January 27 1891, the Evening Post did not expect any lasting benefit to accrue from this decision. Removal of the races to a location outside the town would not result in any lessening of racing, or of its attendant evils. Racegoers would certainly come into Nottingham after a day's sport: 'and it is gravely to be suspected that not a few people in Nottingham will go to the races as of old, and bet on the horses they fancy pretty much as they did in the degenerate days, when Nottingham racecourse was a racecourse.' With the actual decision, however, the Post had no quarrel, agreeing that it was 'scarcely seemly' for the Corporation to be in any way associated with racing while many ratepayers believed the sport to be wicked and demoralising. The leader writer did, however, remind his readers that the Town Council would be financially the poorer for not letting the racecourse each year. As for the Forest, the best thing was to let it alone for the time being. As trade was in Nottingham, the proposal to spend £7,000 on improving the grounds was 'not to be more than talked about'.

Meanwhile, the Race Committee, now a lame duck if ever there was one, was winding up its affairs. The race meeting officials were paid off in lieu of notice, while there was a curious postscript to the Committee's financial activities. Its members had, in the past, personally accepted the Race Committee's liabilities and debts, and had, over the years, converted these into a profit. This had been spent on such projects as improving the Forest, and on local charities such as the Sunday School Union. The Committee held a final balance of £950, and sought the Council's approval for giving it to organizations like the Town Mission, the General Dispensary, and Nazareth House. On March 3 1891, this seemingly innocent proposal was rudely rebuffed by the Town Council, which accepted Coun. Amos Bexon's proposal: 'That as no rent had been received or charged by the Corporation for use of the Race Course, this Council instructs the Race Committee to pay the total amount named in their Report, to the Finance Committee, to be used for Corporation purposes, and thus help to lighten the burdens of many of the struggling Ratepayers, as the Council should at least be just, before being generous.'

One feature of the abandoned racecourse on the Forest was to linger on for a number of years. This was the grandstand, for which the Council made various attempts to find a role. It was offered to the Robin Hood Rifles at one time, and, at another time, was lived in. In 1907 the Public Parks Committee reported that it had been practically unoccupied since the cessation of racing, and was very dilapidated in places. In the absence of any conceivable future use for the grandstand, the Committee asked the Council to agree to its demolition. After several delays, it was eventually pulled down in February 1910.

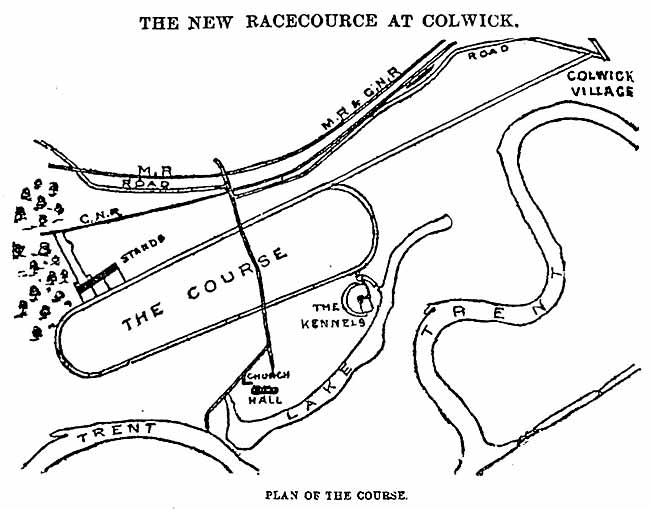

Almost exactly a year after the last meeting on the Forest, Nottingham racegoers heard the news they had been hoping for. The Evening Post of September 26 1891 printed an advertisement, inviting applications for shares in the Nottingham and Colwick Park Racecourse and Sports Co. Ltd., formed for the purpose of acquiring a 30-year lease on the Colwick Park Estate. For 238 years, Colwick Hall and Park had been the property of the Musters (latterly Chaworth Musters) family, who had, however, not used the hall as a permanent residence ever since it had been attacked by Reform rioters in 1831. In 1889 the family had sold out to Colonel Horatio Davies, of London, and Wateringbury, Kent. Col. Davies held the hall and the lower part of the park for a very short period only, before disposing of them. The newspaper pointed out that, before flotation of the company, the site had already been approved as suitable for a racecourse, and a Jockey Club licence obtained. The share capital was £35,000, divided into £1 shares; when the necessary capital was raised, it was proposed to lay out the racecourse (an oval course and a straight mile), paddock, a cycle track, tennis courts, and other sports facilities. The Evening Post referred to the excellent transport access to Colwick Park, with the railway running past the course, and a steamboat landing stage near the hall. The estate offered further business possibilities; fishing rights would be in the hands of the new company, while the hall itself was an interesting building, with potential as a clubhouse. The Post did not comment on one coincidence; Colwick Hall had been largely remodelled by John Carr in 1776, the year before his Forest grandstand was built. The connection with the Forest races was further strengthened by the presence, on the board of directors of the new company, of such former Race Committee stalwarts as Alderman Lambert and Alderman Dennett. The Public Parks Committee had evidently been kept fully informed about developments at Colwick Park; on August 15 1891 they authorized the Borough Engineer 'to make a valuation of the racing apparatus and effects, and dispose of same to new Race Course Co.'

Work on the new buildings at Colwick Park racecourse began in November 1891; the architects were Berridge and Barnes, of Brougham Chambers, Wheeler Gate, Nottingham, and the construction was entrusted to Ald. Dennett’s firm, Dennett & Ingle, of Station Street. By the summer of 1892 all was ready, the Evening Post of August 8 providing a full and enthusiastic description of the new course, which owed its creation to the 'indefatigable efforts' of prominent local racing men, and of 'their admirable secretary, Mr W. Ford'. The paper compared the new racecourse more than favourably with its predecessor: 'In place of the small and inconvenient club stands and rings which were seen on the Forest will be found large and commodious erections for the accommodation of the club members, Tattersall's members, and the more humble votaries of racing who pay the modest half-crown for their afternoon's enjoyment. The winding course, with its peculiar and somewhat dangerous corners, has no repetition at Colwick. Here will be found that indispensable part of a racecourse, a straight mile, a mile, too, which will bear comparison with the best in the country, and on the round course for flat racing, and the one for steeple-chasing, which includes a couple of natural jumps, there are such wide and sweeping bends that the inconvenience of the turns is practically reduced to a minimum.'

The Evening Post re-emphasised how conveniently situated Colwick Park was, alongside the Midland and Great Northern railways: 'The Great Northern have gone to the expense of providing a station which will almost land people on the course, and it is almost certain that the Midland Company will not be long before they follow suit. The Great Northern intend to utilize the opportunity to the full by running a frequent service of trains at small fares. They have, too, studied the comfort of the trainers and horses by building a siding, which runs almost on to the course, and here the horses can be discharged from the trains and by walking across the course for 100 yards be safely housed in the admirable boxes which have been built for them in the rear of the hall.' Despite the Posts’s confident prophecy, a station was never build adjacent to the race course on the Midland Line. On the Nottingham-Grantham line, however, Racecourse Station and the Hall Siding remained in use until the end of the 1950s. The platform of the Hall horse dock still remains, engulfed by vegetation, on the south side of Daleside Road East, which runs at this point along the trackbed of the former Great Northern line.

The newspaper report went on to stress more advantages that Colwick held over the old Forest racecourse, where there had been free admission, except to the enclosures. At the new course, everyone would pay to get in; this, suggested the Post, should enable the promoters to ensure that 'the rowdy and dangerous element which has so disturbed the frequenters of several southern meetings of late will be conspicuous by its absence. Thus much of the evil of the unenclosed meeting will be done away with, and none will grumble to pay for a day's sport when they will be guaranteed immunity as far as possible from the unpleasant attentions of the rowdies and pickpockets who infest the free and open meetings.' The cycle track came in for praise, too; modelled on the Herne Hill track, it promised to be one of the best in the provinces. The journalist also commended the fine condition of the grass on the racecourse, or, as he preferred to call it 'a splendid covering of herbage'. Describing the new buildings in further detail, the report observed that the main stand, 56 yards long, 'although built more with a view to comfort than ornament, is by no means unpretentious in appearance, and is situated so that a complete view can be obtained of the course, no matter upon which part the onlooker is standing'. A smaller stand was forty yards in length, with fifteen rows of seats. Underneath both stands were refreshment facilities, club and Tattersall's members having access to splendid bars 'with all the latest improvements', dining rooms, and smaller, private, luncheon rooms, the comfort of the horses had, as mentioned earlier, not been overlooked; the forty-two boxes in the stable yard were served by 'Nottingham Corporation water so owners and trainers need have no fear of their horses being harmed by bad water.' In conclusion, the Evening Post believed it had said enough to show that the racecourse arrangements were good, but that the public now had to judge for themselves. The acceptances for the first meeting included some very good horses, so some excellent sport was to be expected.

So the scene was set for Friday, August 19 1892, and the first meeting at the new course. The Nottingham Daily Guardian of August 20 reviewed the inaugural day. 'The spectacle at Colwick Park yesterday,' ran its report, 'was actually suggestive of Kempton, and there can be little doubt that there is an important future before the meeting.' The paper recalled the circumstances surrounding the end of racing on the Forest, observing: 'That love of sport which seems to be inherent in the Nottingham man has prevailed, and, being thwarted of the enjoyment of a national pastime within the borough bounds, the local racing men have gone outside to pursue it in a more elaborate and up-to-date manner than was possible previously at the old venue. Perhaps, upon the whole, this is well.....' The new course would, said the Guardian, probably see fourteen days' racing each year, compared with the four of the Forest in its latter days. The opening day would have been 'a brilliant gathering', had not a number of members of the Nottinghamshire aristocracy been absent. It was believed that some had gone away to recover from the strains of the recent Parliamentary election, while others were busy on the grouse moors. For these, or other reasons, the Dukes of St Alban’s, Beaufort, Devonshire, and Durham were not among the first day spectators. The reader must not assume, however, that Colwick Park saw no prominent racegoers; reported as present were Lord Rosslyn, Lord Newark, Sir George Chetwynd, and such members of various county families as Captain Holden of Nuthall Temple and Mr G. H. Fillingham of Syerston Hall. Numerous members of the town Council on hand included Aldermen Lambert, Blackburn and Dennett - the last- named doubtless receiving congratulations on the quality of his firm's building work at the course. The Mayor and Chief Constable of Nottingham had also put in an appearance, adding an even greater respectability (if that were possible) to the assembly.

The weather had been poor on the Thursday, with a threat of thunder. Friday, however, dawned misty, before turning into 'a genial forenoon'. The sun then appeared, showing 'this pretty part of Nottinghamshire almost at its best.' The Daily Guardian reporter was greatly struck by the efficient way in which the railways got racegoers to the course: 'The Great Northern Railway Company followed up their promises of a quick and frequent service to the new racecourse station with a satisfactory performance, as for instance when they ran a special train from King's Cross to Colwick in two hours and 26 minutes, bringing a big contingent from London. There were no fewer than twenty six trains stopped at the Racecourse station yesterday, and the twopenny fare from the Great Northern Station at Nottingham to Colwick proved very popular. The Midland Railway Company, although at present not possessing equal facilities for delivering passengers to the main entrance to the course as their great local rival does, had made a special arrangement to expedite the journey of their customers. For the accommodation of the townsfolk there were many facilities afforded by road as well as rail, and the scene, en route, was very animated.' Although the first day of the new meeting was not quite the dressy function which had been expected, remarked the paper, 'there were several striking costumes worn.'

And the racing itself? This was judged to have been excellent. Of the six races on the card, five had resulted in good finishes. The very first race on the Colwick Park course, the Bestwood Stakes, was marred by a mishap, when a horse named Overcast slipped, and threw its rider, Weldon. Though severely shaken, the jockey rode again later that afternoon, but, not surprisingly, failed to finish in the first three. Races with local names featured again; these included the Rufford Abbey Plate and the Oxton Selling Plate. The main race of the day, the Welbeck Abbey Plate, was won by Mr H. McCalmont's Whisperer, by three quarters of a length from Simon Renard, with Day Dawn beaten into third place by a head. There was some doubt about the placings, many onlookers feeling that Day Dawn had just come second. The owner of Simon Renard was just one of the day's notable absentees from Colwick Park; he would, no doubt, have been surprised to know that, half a century later, his son would be the most famous man in England: the owner was Lord Randolph Churchill.

The second and last day of the inaugural meeting took place on a hot and sunny Saturday. The Nottingham Daily Express remarked that sunny weekends always brought out the crowds, and that there was indeed a crowd at Colwick. 'The means of getting there were somewhat severely taxed. Buses and wagonettes, four wheelers and hansoms were as usual pressed into service, a numberless company walked through the dust that they made, while trains were running every few minutes from the Great Northern Railway Station, and they were fortunate who obtained sitting room. The turnstiles at the entrance kept up a continual click-click.....' The Daily Express asserted that the Colwick Park course was already being favourably compared with Derby, one of the best Midland racecourses, and hoped that, with larger stake-money, it would attract more top trainers. The organisation of the meeting was exemplary, 'and Mr W. Ford, the secretary, and his courteous father and amiable brothers are to be heartily congratulated upon the great success which has crowned their earnest efforts to make the meeting known and recognised.' Chief race on the card was the Nottinghamshire Handicap, raised in value since the Forest days from £500 to £1,000. This was easily won by Golden Garter, from Glory Smitten, which had been a winner at the final meeting on the Forest. The day ended in anti-climax, as Kentigern walked over for the Elvaston Castle Plate. Following this, 'The big crowd disappeared with astonishing rapidity, train after train steaming away from the fine platform which the Great Northern Railway have so enterprisingly erected, and so admirable were the arrangements at the Racecourse station that it was almost as easy to take train for London and other distant places as it was for Nottingham.' The racecourse authorities would have had good reason for feeling that the local press had done them proud in terms of publicity and praise; so, one feels, would the directors of the Great Northern Railway.

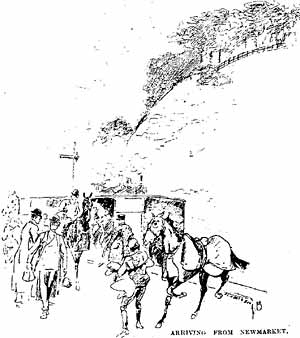

Before the close of the nineteenth century the new racecourse had become firmly established as part of the Nottingham scene. A glimpse of the bustle of a meeting at Colwick Park in 1898 was afforded by the local magazine City Sketches in its issue of August 1 of that year. A writer and illustrator calling himself 'JB’ gave his impressions of the scene. He considered that Nottingham people had the racecourse in the hollow of their hand, and that it was 'No trouble to get there'. This was, perhaps, stretching the truth a bit; building at Sneinton had not yet approached Colwick level crossing, while a tram service along Colwick Road was still almost a decade away. At the Hall racehorse siding, 'JB' met a racing man who claimed that Colwick was the finest course in England, a view with which he agreed. He described the procession of stable lads and horses, from a special train just arrived from Newmarket, to the stable-yard. Though close to the hall, this was 'in nowise situated so as to intrude itself, destroy, or counteract the effect of that pearl of architecture.' Of the actual racing, he had a confused, but lively memory, and had no idea which horse had won: 'The thundering rush of a body of men and horses I had seen - the vivid flashes of glittering silk I had noticed as they passed me by; I had heard the whips crack on the horses' flanks, but seen the 'winner' - no-no indeed!' Among the types observed by 'JB' at the meeting were 'the ladies in their dainty summer dresses, the rustic trainer with the flourishing face, the swell trainer with the lordly manners ........ ' His final judgement would have pleased the racecourse directors: 'All', he remarked, 'is as pretty and neat as hands can make it.'

This is neither a history of racing at Colwick, nor of Colwick Hall, so little more remains to be said here. Since the inception of racing on the new course, the hall has seen almost continuous use as a public house, hotel, or restaurant, under various managements. It was for many years owned by the racecourse company, and leased to the Home Brewery. Then, in 1965, the City Council bought the hall and park, and released them. Now Colwick Hall Hotel, the hall is a popular restaurant, with private hire facilities for such functions as wedding receptions. What one wonders, would those worthy Council members, temperance bodies, and religious organisations of 1890 have thought of all this - the Corporation, seventy five years on, becoming owner, not only of a racecourse once again, but also of a licensed premises? Surely they would, in the words of the Evening Post long ago, have considered such a development to be 'scarcely seemly'.

1. Mr Lambert's home was Lenton Firs, which gave its name to one of the races at the Nottingham meeting.

2. Goose Fair, 1890, also took place in that week; one hopes that Mr Green had taken this into consideration.

< Previous